Battle of Cape Gloucester

The Battle of Cape Gloucester was fought in the Pacific theater of World War II between Japanese and Allied forces on the island of New Britain, Territory of New Guinea, between 26 December 1943 and 16 January 1944. Codenamed Operation Backhander, the US landing formed part of the wider Operation Cartwheel, the main Allied strategy in the South West Pacific Area and Pacific Ocean Areas during 1943–1944. It was the second landing the US 1st Marine Division had conducted during the war thus far, after Guadalcanal. The objective of the operation was to capture the two Japanese airfields near Cape Gloucester that were defended by elements of the Japanese 17th Division.

| Battle of Cape Gloucester | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War of World War II | |||||||

US Marines hit three feet of rough water as they leave their LST to take the beach at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, 26 December 1943. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

310 killed 1,083 wounded | 2,000 killed | ||||||

Location within Papua New Guinea  Battle of Cape Gloucester (Pacific Ocean) | |||||||

The main landing came on 26 December 1943, when US Marines landed on either side of the peninsula. The western landing force acted as a diversion and cut the coastal road near Tauali to restrict Japanese freedom of movement, while the main force—landing on the eastern side—advanced north towards the airfields. The advance met light resistance at first but was slowed by the swampy terrain which channeled the US troops onto a narrow coastal trail. A Japanese counterattack briefly slowed the advance, but by the end of December the airfields had been captured and consolidated by the marines. Fighting continued into early January 1944 as the marines extended their perimeter south from the airfields towards Borgen Bay. Organized resistance ceased on 16 January 1944 when marines captured Hill 660; however, mopping up operations in the vicinity continued into April 1944 until the marines were relieved by US Army forces.

Background

Geography

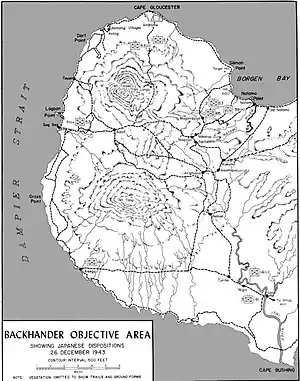

Cape Gloucester is a headland that sits on the northern peninsula at the west end of the island of New Britain, which lies to the northeast of mainland New Guinea. It is roughly opposite to the Huon Peninsula, from which it is separated by Rooke Island with the intervening sea lane divided into the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits.[1] At the time of the battle it was part of the Territory of New Guinea. It is 230 miles (370 km) west of Rabaul and 245 miles (394 km) northeast of Port Moresby.[2] The peninsula on which Cape Gloucester sits consists of a rough semi-circular coast, extending from Lagoon Point in the west to Borgen Bay in the east. At the base of the peninsula is Mount Talawe, a 6,600-foot (2,000 m) extinct volcano, which runs laterally east to west. Southwest of Talawe, a semi-active volcano, Langila, rises 3,800 feet (1,200 m), while further to the south, the extinct volcano Mount Tangi rises to 5,600 feet (1,700 m).[2] The area is densely vegetated with thick rainforest, sharp kunai grass and deep mangrove swamps. In 1943, there were only a few beaches suitable for landing operations, and there were no roads around the coast along which troops and vehicles could quickly advance.[3]

Temperatures ranged from 72 to 90 °F (22 to 32 °C), with high humidity. Rainfall was heavy, especially during the northwest monsoon season that ran until February. Air operations in this period could be mounted from Finschhafen, but after February the climate there was expected to restrict air operations, which would have to be conducted from Cape Gloucester. The climate dictated the timetable for the Cape Gloucester operation.[4] In 1943, an Allied intelligence survey of the area estimated the local population around Cape Gloucester at around 3,000. There were numerous villages spread across four main areas: on the western coast, near Kalingi; on the western bank of the Itini River in the south; inland from Sag Sag and towards Tauali (on the western coast); and to the east of Mount Tangi, around Niapaua, Agulupella and Relmen. Prior to the Japanese invasion of New Britain in 1942, there had been two European missions around Cape Gloucester: a Roman Catholic mission at Kalingi and an Anglican one at Sag Sag.[5]

Before the war a landing ground had been established on the relatively flat ground that lay at the apex of the peninsula. Following the Japanese invasion of New Britain in early 1942, the landing ground had been developed into two airstrips (the larger of the two being 3,900 feet (1,200 m) long).[6] The area was assessed by Allied intelligence as largely being unsuitable for large-scale development, with reefs to the south, west and north hampering the movement of large vessels, and a lack of protected anchorages suitable for such vessels. The few areas suitable for such vessels were open to the sea and were not considered perennial, being affected by the changing seasons.[7] Nevertheless, small craft could operate along the coast,[7] and Borgen Bay had been developed into a staging area for barge operations between mainland New Guinea and the main Japanese base around Rabaul on the eastern end of New Britain.[6]

Strategic situation

By late 1943, the fighting in New Guinea had turned in the favor of the Allies after a period of hard fighting. The Japanese drive on Port Moresby during 1942 and early 1943 had been defeated during the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Kokoda Track campaign.[8] The Japanese beachhead at Buna–Gona was subsequently destroyed, albeit with many casualties.[9] The Japanese had been forced to abandon their efforts on Guadalcanal, and the Allies had secured the Salamaua region.[10][11] The Allies then seized the initiative and implemented Operation Cartwheel, a series of subordinate operations aimed at the reduction of the Japanese base at Rabaul and then severing of lines of communication in the South West Pacific Area,[12] as the Allies advanced towards the Philippines where operations were planned for 1944–1945.[13] The Australians had secured Lae by 16 September 1943, and operations to capture the Huon Peninsula had begun in earnest shortly after, to secure Finschafen before a drive on Saidor.[14] A secondary effort pushed inland from Lae through the Markham and Ramu Valleys, with the two drives eventually aiming toward Madang.[15][16] As Allied forces began to make headway on the Huon Peninsula, Allied attention then turned to securing their seaward flank on the other side of the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits.[17]

On 22 September 1943, General Douglas MacArthur issued orders for the invasion of New Britain, codenamed Operation Dexterity. This operation was conceived with several phases, with the broad Allied scheme of maneuver being to secure all of New Britain west of the line between Gasmata and Talasea on the north coast.[18] Within this scheme, Operation Backhander was a landing around Cape Gloucester aimed at the capture, and expansion of, two Japanese military airfields. This was to contribute to the increased isolation and harassment of the major Japanese base at Rabaul, which was subjected to heavy aerial bombing in October and November,[19] as part of ongoing efforts to neutralize the large Japanese garrison there without the need to assault it head on.[20] A secondary goal was to ensure free Allied sea passage through the straits separating New Britain from New Guinea. Amongst Allied commanders there was some debate about the necessity of invading New Britain. Lieutenant General George Kenney, the US air commander, believed that the landing at Cape Gloucester was unnecessary. He believed that it would take too long for the airfields to be developed and that the pace of Allied advance would ultimately outstrip their usefulness. Nevertheless, army and naval commanders felt it was necessary to secure convoy routes through the Vitiaz Strait to support operations in western New Guinea and to the north.[21][22]

The landing at Gasmata was later cancelled and replaced with a diversionary landing around Arawe, with the plan being to potentially establish a PT boat base there.[23] Believing that the Allies could not bypass Rabaul as they attempted to advance towards the Japanese inner perimeter and would seek to capture it as quickly as possible, the Japanese sought to maintain a sizeable force for the defense of Rabaul, thus reducing the forces available for the defense of western New Britain.[24]

Prelude

Opposing forces

Responsibility for the seizure of western New Britain was given to Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Alamo Force.[25] For the Cape Gloucester operation, US planners assigned the 1st Marine Division (Major General William H. Rupertus) which had previously fought on Guadalcanal.[26][27] The operation would be the 1st Marine Division's second landing of the war.[28] Initial planning had envisaged an airborne landing from the 503rd Parachute Infantry near the airfields in conjunction with a two-pronged seaborne landing either side of the cape, with two battalions of the 7th Marine Regiment advancing on the airfields from the beaches north of Borgen Bay, while another blocked ingress and egress routes along the opposite coast around Tauali. However, the airborne landing was later removed from the plan due to concerns about overcrowding of staging airfields and possible delays due to weather. To compensate, the size of the seaborne assault forces was increased.[29] The main force assigned to the assault was drawn from the 7th Marine Regiment (Colonel Julian N. Frisbie) reinforced by the 1st Marine Regiment (Colonel William J. Whaling). In addition, the 5th Marine Regiment (Colonel John T. Selden) formed the reserve. Artillery was provided by the 11th Marines (Colonel Robert H. Pepper and later Colonel William H. Harrison).[30] These troops were organized into three combat teams, designated 'A' to 'C': the 5th Marines formed Combat Team 'A'; the 1st Marines formed Combat Team 'B' and the 7th Marines were Combat Team 'C'.[31]

In mid-1943, elements of the 1st Marine Division had still been in Australia, where they had been withdrawn following the fighting on Guadalcanal. Around this time, preliminary landing rehearsals had been conducted around Port Phillip Bay, prior to the division's movement to the forward assembly areas in New Guinea in August and September; however, the majority of Allied amphibious assets were tied up with operations around the Huon Peninsula, which meant that only limited rehearsals could take place until after November 1943. The combat teams moved into three staging locations (Milne Bay, Cape Sudest and Goodenough Island) after which further practice landings were conducted around the Taupota Bay area, before they concentrated at Cape Sudest in the Oro Bay area, southeast of Buna in December 1943.[32][33]

The US troops were opposed by elements of the Japanese 17th Division (Lieutenant General Yasushi Sakai), which had previously served in China before arriving on New Britain in October and November 1943. These troops were known as "Matsuda Force", after their commander, Major General Iwao Matsuda and consisted of the 65th Brigade, with the 53rd and 141st Infantry Regiments and elements of the 4th Shipping Group. These troops were supported by field and anti-aircraft artillery, and a variety of supporting elements including engineers and signals troops. Just prior to the battle, there were 3,883 troops in the vicinity of Cape Gloucester.[34][35] Matsuda's headquarters had been at Kalingi, along the coastal trail northwest of Mount Talawe, within 5 miles (8.0 km) of the Cape Gloucester airfields but after the Allied bombardment prior to the battle, it had been moved to Egaroppu, closer to Borgen Bay. The headquarters at Kalingi was taken over by the Colonel Koki Sumiya, commander of the 53rd Infantry Regiment, which defended the airfields primarily with the regiment's 1st Battalion, supported by elements of two artillery battalions, a heavy weapons company and a battalion of anti-aircraft guns.[36] The 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry Regiment was in reserve around Nakarop,[37] while the 141st Infantry Regiment (Colonel Kenshiro Katayama) was positioned well to the south around Cape Bushing.[38] At the time of the fighting around Cape Gloucester, the effectiveness of these troops had been degraded by disease and lack of supplies, due to interdiction of the Japanese coastal supply barges.[39] Air support was available from the naval 11th Air Fleet and 6th Air Division.[40]

Preparations

The landing on Cape Gloucester was scheduled for 26 December. Prior to the operation, planners directed that a stockpile of supplies – enough for a month of combat operations – be built up around Oro Bay, and this was in place by 16 December and would be shuttled to Cape Gloucester by landing craft as required.[41] The day before, supporting operations began, when the US Army 112th Cavalry Regiment landed at Arawe on the south-central coast, to block the route of Japanese reinforcements and supplies from east to west and as a diversion from the Cape Gloucester landings.[42][39] The operation around Arawe succeeded in diverting about 1,000 Japanese troops from Cape Gloucester.[43]

For several months before the landings, the area around the airfields and the coastal plain between Cape Gloucester and Natamo, south of Borgen Bay, was bombed by Allied aircraft, mainly from the US Fifth Air Force.[44] Japanese entrenchments were destroyed and the airfields around Cape Gloucester were put out of action from November.[45][43] A total of 1,845 sorties were launched by US aircraft around Cape Gloucester, with the expenditure of almost 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition and 3,926 tonnes (3,926,000 kg) of bombs.[46] Diversionary air raids were also made by AirSols aircraft in the days before the assault, focused on the Japanese airfields around Rabaul, while naval aircraft bombed Kavieng. Raids were also launched against Madang and Wewak.[44] Meanwhile, the Allies undertook extensive aerial reconnaissance of the area, while ground teams of marines, Alamo Scouts and coastwatchers were landed at various locations except Borgen Bay over three separate occasions from PT boats between September and December 1943.[47][48]

Japanese defensive planning was focused upon holding the airfield sector. Bunkers, trenches and fortified positions were built along the coast to the east and west, with the strongest position being established to the southeast, to defend against an approach through the flat grasslands. A complex was also established at the base of Mount Talawe, affording a commanding view of the airfields, which were held by a battalion of infantry supported by service troops and several artillery pieces. To the east of the peninsula, the beaches around Silimati Point, which were bounded by heavy swamps, were largely left unfortified, the Japanese defensive scheme based on holding several high features, Target Hill and Hill 660 and maintaining control of lateral tracks, rapidly to move forces in response to an attack.[49]

Embarkation

The Allied plan called for a two-pronged landing at several beaches to the east and west of the peninsula, followed by an advance north towards the airfields at Cape Gloucester. Final rehearsals were carried out on 21 December after which the troops embarked on their vessels early on Christmas Day at Oro Bay and Cape Cretin, near Finschhafen. The convoy, designated Task Force 76 under Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey,[50] consisted of nine APDs, 19 Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs), 33 Landing Ship Tank (LSTs), 14 Landing Craft Mechanized (LCMs) and 12 Landing Craft Tank (LCTs), escorted by 12 destroyers as well as the task force flagship Conyngham, three minesweepers and two rocket-carrying DUKWs that were carried aboard the LCMs. These two amphibians would support the western landings, while two LCIs had been similarly modified to support the eastern landing.[51]

The troops were carried aboard the APDs, while the LSTs carried the heavy vehicles including bulldozers, tanks and trucks. In order to supply the force, a total of 20 days of supply of rations was detailed for assault troops, while the follow-on troops were to land with 30 days of supply. Both groups were to carry three units of ammunition resupply, while five days were needed for anti-aircraft weapons. Nevertheless, space was at a premium and in some instances, this could not be met. In order to speed up the unloading process and reduce congestion on the eastern beaches, a mobile loading scheme was devised with the supplies preloaded directly on 500 2.5-ton trucks. These vehicles would arrive on the beaches with the first echelon that would land the assault troops in the morning, and would be able to drive straight off the LSTs and unload their cargo at several dumps ashore before re-embarking on LSTs assigned to the second echelon that would land in the afternoon on the first day with the follow-on troops. Medical teams, including doctors and corpsmen, were assigned to each transport and some LSTs, and these personnel would form part of an evacuation chain that would see casualties transported back to Cape Sudest where an 88-bed floating hospital was established aboard an LST, which would serve as a casualty-receiving station prior to onward movement to base hospitals ashore.[41][52]

This force was escorted by United States Navy (USN) and Royal Australian Navy (RAN) cruisers and destroyers from Task Force 74, under Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley of the Royal Navy. Maintaining a speed of 12 knots, the convoy proceeded through the Vitiaz Strait towards Cape Gloucester, traversing between Rooke and Sakar Islands. As they made their way towards their objective, Allied patrol boats operated to the north and western approaches, in the Dampier Strait and the southern coast of New Britain.[53][44] While heading towards their objective, the convoy was spotted by a Japanese reconnaissance plane as well as an observer around Cape Ward Hunt. As a result, their progress was reported to Rabaul. However, the commander of the Japanese Southeast Area Fleet, Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, incorrectly assessed that the convoy was bound for Arawe as reinforcements, and subsequently ordered a heavy air attack there instead of around Cape Gloucester with 63 Zero fighters and 25 bombers from Rabaul.[44][54]

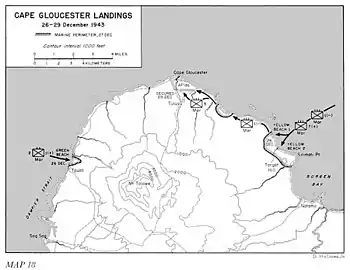

Battle

The main operation began just after dawn on 26 December with a naval barrage on the Japanese positions on the cape followed by air attacks by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).[53][55] A total of 14 squadrons from the 1st Air Task Force under Brigadier General Frederick A. Smith, were provided for close air support, of which nine were bomber squadrons and five were attack. In addition, several fighter squadrons flew combat air patrols to negate the threat from Japanese aircraft: one squadron covered the approaching convoy, three would cover the landing beaches, and another would cover the seaborne elements that would withdraw in the afternoon.[56][51] These attacks and an aerial smoke screen were followed by the landing of the 1st Marine Division, at Yellow Beaches 1 and 2, to the east near Silimati Point and Borgen Bay, about 5 miles (8.0 km) southeast of the airfield and a diversion at Green Beach, to the west at Tauali, about 6.5 miles (10.5 km) from Cape Gloucester.[47] The main assault came at Silimati Point with only one battalion landing in the west.[57] After being transported aboard the APDs from Cape Sudest, the force came ashore aboard landing craft of various types including, LSTs and LCIs.[58]

_during_pre-invasion_bombardment_of_Cape_Gloucester.jpg.webp)

Western landing

The diversionary western landing at Tauali (Green Beach), on the Dampier Strait side of the peninsula was assigned to Landing Team 21 (LT 21), consisting of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines with a battery of artillery from the 11th Marines. Escorted by two destroyers and two patrol boats, the force was embarked upon 31 landing craft of various types (five LCIs, 12 LCTs and 14 LCMs). They carried with them 20 days of rations and six units of artillery ammunition. After departing Oro Bay with the main convoy, this force had broken off around Finschhafen and proceeded on its own through the Dampier Strait.[59] After a preliminary naval and aerial bombardment around 07:30, the Japanese defenses around Green Beach were found abandoned. LT 21 experienced no opposition coming ashore, preceded by heavy preparatory fires including rockets fired from several amphibious vehicles.[60][43] The beachhead was established by 08:35 and all first day objectives had been secured by 10:00. Due to interference from the surrounding terrain, the marines were unable to raise their divisional headquarters, and were instead had to relay messages through headquarters Sixth Army (Alamo Force).[61] By nightfall, the marines had secured a perimeter and had cut the coast road, establishing a road block.[60] This prevented the Japanese from using it to reinforce their positions around the airfields, but a secondary route, to the east of Mount Talawe, remained open to the Japanese, having gone undetected by US intelligence.[62]

Shortly after the western landing, the Japanese dispatched two companies of the 53rd Infantry Regiment to respond.[63] In the days that followed, the marines clashed with small groups of Japanese, and Japanese artillery and mortars fired on the US perimeter from Dorf Point. Patrol clashes increased until early morning on 30 December when the two companies of the 53rd Infantry attacked the marines around Coffin Corner, exploiting the concealment of a heavy storm and darkness to launch a concentrated assault along a narrow avenue of approach between two defended ridges. Supported with mortars, machine guns and artillery, a five-hour firefight followed before the assault was turned back. Casualties amounted to 89 killed and five captured for the Japanese, against six marines killed and 17 wounded. Following this, there were no further assaults on the western perimeter. Artillery fell on the position on 31 December, but was met counterbattery fire from the 11th Marines who labored to get their guns into action despite the terrain. Although the Japanese sought mainly to avoid contact as most withdrew to support the fighting on the east coast, patrol actions continued throughout early January 1944, when contact was established around Dorf Point with a company-sized patrol from the 5th Marines that had set out overland from the eastern lodgment. The wounded and heavy equipment were subsequently embarked on 11 January, having been hampered by poor weather previously, and LT 21 then collapsed its position, marching east towards the airfields, and on 13 January they linked up with the main body of US troops, who had captured the airfields in late December.[64]

Eastern landing and advance to the airfields

The remainder of Task Force 76 consisting of 9 APDs, 14 LCIs, and 33 LSTs were allocated to the eastern zone (Yellow Beaches 1 and 2).[51] The 7th Marines were to go ashore first and were tasked with securing the beachhead, while the 1st Marines – less the battalion assigned to the diversionary landing around Tauali – would follow them up after the initial assault, and would pass through their lines to begin the advance north towards the airfield.[65] The 5th Marines would remain embarked as a floating commander's reserve and would only be released on Krueger's orders.[66]

As the task force moved into position, the approaches to the beach were marked and cleared during the darkness, and at 06:00, an hour and 45 minutes prior to H-Hour, a heavy naval bombardment began, with the cruisers engaging targets around the airfields, as well as around the beaches and towards Target Hill. As H-Hour approached, the escorting destroyers also joined in the bombardment, followed by a carefully co-ordinated aerial bombing raid with five squadrons of B-24s, and one squadron of B-25s, attacking Target Hill.[67] The first wave of assault troops disembarked from the APDs and were loaded into 12 Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVPs): six were bound for Yellow 1 and the other six for Yellow 2. While the APDs withdrew, the LCVPs began their run to the shore. After the B-25s made a final strafing run over the beach, two rocket-equipped LCIs stationed to the flanks fired onto the beach defenses.[68]

Drifting smoke from the aerial bombardment of Target Hill, obscured the beaches and the approaches, and briefly hampered the landing with some troops coming ashore in the wrong spot. Nevertheless, the first wave made landfall around Yellow 1 one minute after H-Hour followed two minutes later at Yellow 2. There was no opposition in the vicinity of these two beaches, but the small group from the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines which landed 300 yards (270 m) northwest of Yellow 1 by mistake came under fire from machine guns firing at maximum range from a number of bunkers after pushing through the thick jungle to locate the coastal trail. Throughout the morning, follow-up troops from the remainder of the 1st Marines came ashore and pushed through the 7th Marines, to begin the advance north towards the airfields. The landing area to the north of Borgen Bay, was surrounded largely by swamp, with only a small narrow beach along which the Marine infantry and their supporting Sherman tanks from the 1st Tank Battalion could advance towards the airfields. This slowed the advance inland and resulted in heavy congestion on the beaches, hampering the unloading process.[69][70]

After initially being diverted towards Arawe in the morning, Japanese aircraft, after refueling and rearming at Rabaul began attacking the Allied ships around the landing beaches around 14:30, resulting in the loss of the destroyer USS Brownson with over a hundred of her crew and casualties aboard the destroyers USS Shaw and Mugford. Nevertheless, around 13,000 troops and about 7,600 tons of equipment were pushed ashore during the first day of the operation on either side of the cape, and the attacking Japanese aircraft suffered losses to US fighters and ship-borne anti-aircraft fire.[71] Opposition in the main landing area was limited initially to rear-area troops that had been overrun but a hasty counterattack by the 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry Regiment (Major Shinichi Takabe), which had marched from Nakarop, lasted through the afternoon and evening of the first day, falling mainly against the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines under Lieutenant Colonel Odell M. Conoley.[72][73] By the end of the day, the 7th Marines held the beachhead, while the 11th Marines had brought their artillery pieces ashore and the 1st Marines had begun a slow advance north, forced into a long column along the narrow trail.[69]

The following day the marines advanced westward, pushing 3 miles (4.8 km) towards their objective, before reaching a Japanese blocking position, identified by the marines as Hell's Point, on the eastern side of the airfields. This position was well concealed, and equipped with anti-tank and 75 mm field guns.[74][75] Teams from the 19th Naval Construction Battalion (designated as the 3rd Battalion, 17th Marines[76]) worked to improve the routes along which the US forces were advancing as large quantities of supplies were landed.[77] Amphibian landing vehicles were used to ferry ammunition forward,[78] but the volume of traffic, coupled with the heavy rain, churned up the narrow coastal road.[79] As a result, the movement of combat supplies forward from Yellow Beach, as well as evacuation of the wounded back from the engagement areas, proved difficult. On 28 December, a secondary landing beach – Blue Beach – was established about 4 miles (6.4 km) closer to the fighting to reduce the distance supplies had to travel ashore.[80] At the same time, the blocking position was attacked and US armor was brought up. Nine Marines were killed and 36 were wounded, while Japanese losses amounted to at least 266 killed.[81]

The 5th Marines, which had been in reserve for the initial landing, were landed on 29 December. There was some confusion during the landing due to a last minute change in orders for the regiment to land on Blue Beach instead of Yellow Beach 1 and 2. As a result, the regiment came ashore in both locations, with those who arrived on the Yellow Beaches route marching to Blue Beach or being ferried by truck.[82] After establishing themselves ashore, the 5th Marines carried out a flanking move to the south-west, while the 1st Marine Regiment continued to advance along the coast. By the end of the day, the marines had broken through the Japanese defenses and were in control of most of the airfield.[39][83] Japanese air attacks ended on 29 December, when bad weather set in. This was followed by much US air activity around Rabaul, which prevented further air attacks on Cape Gloucester.[84] During the final days of December, the marines overran the airfield and expanded their perimeter, incorporating Razorback Ridge, a key feature about 1,500 yards (1,400 m) to the south of No. 2 Strip running north to south.[85][86] In early January, Company E, from the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines effected a link up with the western lodgment around Dorf Point on the western coast.[62]

Advance to Borgen Bay

In the weeks that followed the capture of the airfield, US troops pushed south towards Borgen Bay to extend the perimeter beyond Japanese artillery range. In this time, further actions were fought by the 5th and 7th Marines against the remnants of the 53rd Infantry Regiment and the 141st Infantry Regiment, which had undertaken a march north across difficult terrain from Cape Bushing, following the initial landings.[63] On 2 January, there was a sharp engagement around Suicide Creek, when the advancing marines came up against a heavily entrenched defending force from the 53rd Infantry. Held up by strong defenses that were well concealed amongst the dense jungle, the marines were halted and dug-in temporarily around Suicide Creek. The following day, a reinforced company from the Japanese 141st Infantry Regiment launched an unsuccessful counterattack on the US troops around Target Hill. This was followed by renewed fighting around Suicide Creek, as the Japanese put up a stubborn defense, which was eventually overcome with the assistance of tanks and artillery on 4 January.[87]

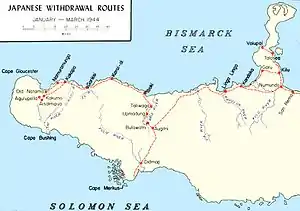

After reorganizing on 5 January, US troops secured Aogiri Ridge and Hill 150 on 6 January.[88] This was followed by an action towards the high ground around Hill 660.[89][90] Slowed by bad weather, rugged terrain and Japanese resistance, progress for the marines around Hill 660 was slow. The position was finally secured on 16 January 1944 following three days of fighting in which 50 marines and over 200 Japanese were killed. The capture of this position represented the end of Japanese defensive operations in the Cape Gloucester and Borgen Bay areas.[91] Following this, Matsuda withdrew with around 1,100 troops, ceding the area to the Americans, who captured his command post intact.[92]

Base development

The Base Engineer and his operations staff landed on 27 December 1943 and completed a reconnaissance of the two Japanese airfields by 30 December. They found that they were 3 feet (0.91 m) deep in kunai grass and that the Japanese had neither attempted to construct proper drainage nor to re-grade the airstrips. They decided not to proceed with any work on No. 1 Airstrip and to concentrate on No. 2. The 1913th Engineer Aviation Battalion arrived on 2 January, followed by the 864th Engineer Aviation Battalion on 10 January and the 841st Engineer Aviation Battalion on 17 January. Work hours were limited by blackout restrictions imposed by the Task Force Commander, which limited work to daylight hours until 8 January 1944 and by heavy and continuous rain from 27 December 1943 until 21 January 1944, averaging 10 inches (254 mm) a week. Grading removed 3 to 6 feet (0.91 to 1.83 m) of material, mostly kunai humus, from two-thirds of the area. The subgrade was then stabilized with red volcanic ash that had to be hauled from the nearest source 8 miles (13 km) away. Marston Mat was then laid over the top but this did not arrive until 25 January 1944, resulting in further delay. By 31 January, 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of runway was usable and by 18 March a 5,200-foot (1,600 m) runway was complete. Natural obstacles prevented the runway being lengthened to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) as originally planned but there were four 100-by-750-foot (30 by 229 m) alert areas, 80 hardstands, a control tower, taxiways, access roads and facilities for four squadrons.[93]

.jpg.webp)

A C-45 had landed on the runway at Cape Gloucester in January, followed by a C-47. Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, the commander of Alamo Force, inspected the airstrip with Brigadier General Frederic H. Smith, Jr., on 9 January 1944. They estimated that the 8th Fighter Group could move in as early as 15 January. This did not prove feasible; the airbase was not finished and was at capacity with transport aircraft bringing in much-needed supplies. The 35th Fighter Squadron arrived on 13 February, followed by the 80th Fighter Squadron on 23 February. Heavy rains made mud ooze up through the holes in the steel plank, making the runway slick. This did not bother the 35th Fighter Squadron which flew nimble and rugged P-40 Kittyhawks but the P-38 Lightnings of the 80th Fighter Group found themselves overshooting the short runway. Major General Ennis C. Whitehead, the commander of the Fifth Air Force Advanced Echelon (ADVON), decided to move the 8th Fighter Group to Nadzab and replace it with RAAF Kittyhawk squadrons from Kiriwina.[94] No. 78 Wing RAAF began moving to Cape Gloucester on 11 March. No. 80 Squadron RAAF arrived on 14 March, followed by No. 78 Squadron RAAF on 16 March and No. 75 Squadron RAAF two days later. No, 78 Wing provided close air support for the 1st Marine Division, assisted the PT boats offshore and provided vital air cover for convoys headed to the Admiralty Islands campaign. Operations were maintained at a high tempo until 22 April, when No. 78 Wing was alerted to prepare for Operations Reckless and Persecution, the landings at Hollandia (Jayapura) and Aitape.[95]

To support air operations, 18,000 US barrels (2,100,000 L; 570,000 US gal; 470,000 imp gal) of bulk petroleum storage was provided, along with a tanker berth with connections to the five storage tanks, which became operational in May 1944. The 19th Naval Construction Battalion worked on a rock-filled pile and crib pier 130 feet (40 m) long and 540 feet (160 m) wide for Liberty ships. It was not completed before the 19th Naval Construction Battalion left for the Russell Islands, along with the 1st Marine Division, in April 1944. Other works included 800,000 square feet (74,000 m2) of open storage, 120,000 square feet (11,000 m2) of covered warehouse storage and 5,400 cubic feet (150 m3) of refrigerated storage; a 500-bed hospital was completed in May 1944 and a water supply system with a capacity of 30,000 US gallons (110,000 L; 25,000 imp gal) per day was installed. Despite problems obtaining suitable road surface materials, 35 miles (56 km) of two-lane all-weather roads were provided, surfaced with sand, clay, volcanic ash and beach gravel. Timber was obtained locally, and a sawmill operated by the 841st Engineer Aviation Battalion produced 1,000,000 board feet (2,400 m3) of lumber.[96]

Aftermath

Analysis and statistics

Casualties during operations to secure Cape Gloucester amounted to 310 killed and 1,083 wounded for the Americans.[90] Japanese losses exceeded 2,000 killed in the December 1943 to January 1944 period.[97] Ultimately, according to historian John Miller, Cape Gloucester "never became an important air base".[90] Plans to move Thirteenth Air Force units there were cancelled in August 1944.[98] In assessing the operation, historians such as Miller and Samuel Eliot Morison have argued that it was of limited strategic importance in achieving the Allied objectives of Operation Cartwheel.[99] Morison called it a "waste of time and effort".[3] Nevertheless, the airstrip played a vital role in supporting the Admiralty Islands operation commencing in February 1944 and as an emergency landing field for aircraft damaged in raids on Kavieng and Rabaul; it remained in use until April 1945. In June, the base at Cape Gloucester became part of Base F at Finschhafen.[98]

Subsequent operations

Elsewhere, US and Australian forces conducted the Landing on Long Island, 80 miles (130 km) to the northwest, where a radar station was established in December.[89] Alamo Force switched its attention to the landing at Saidor in January 1944 as part of the next stage of operations in New Guinea.[100] In mid-January, the 17th Division commander, Yasushi Sakai, sought permission to withdraw his command from western New Britain.[101] On 16 February, US patrols from Cape Gloucester and Arawe linked up around Gilnit.[102] A company from the 1st Marines landed on Rooke Island on 12 February aboard six LCMs to ensure it was clear of Japanese troops. After coming shore unopposed, the marines sent out patrols to reconnoiter the island. Finding it abandoned, they returned to Cape Gloucester on the 20th [103] Commencing on 23 February, the Japanese forces sought to disengage from the Americans in western New Britain and move towards the Talasea area.[90] Marine patrols kept up the pressure, with several minor engagements being fought in the center of the island and along its north coast.[104]

Mopping up operations around Cape Gloucester continued throughout early 1944, although by February 1944 the situation had stabilized enough for US planners to begin preparations to expand the lodgment further east. In early March 1944, the Americans launched an operation to capture Talasea on the northern coast of New Britain, while following up a general Japanese withdrawal towards Cape Hoskins and Rabaul.[105][106] The 1st Marine Division was relieved around Cape Gloucester on 23 April 1944, and were replaced by the US Army's 40th Infantry Division,[107] which arrived from Guadalcanal.[108] A lull on New Britain followed as the US confined their operations largely to the western end of the island, having decided to bypass Rabaul, while the Japanese stayed close to Rabaul at the opposite end of the island.[109] Responsibility for operations on New Britain was later transferred from US forces to the Australians. In November 1944, they conducted the Landing at Jacquinot Bay for a limited offensive with the Battle of Wide Bay–Open Bay securing the bays, to confine the larger Japanese force to the Gazelle Peninsula, where they remained until the end of the war.[110]

References

- Morison 1975, Map, p. 375.

- Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area 1943, p. 1.

- Morison 1975, p. 378.

- Casey 1951, p. 193.

- Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area 1943, pp. 1 & 17–18.

- Morison 1975, pp. 378–379.

- Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area 1943, pp. 2–3.

- James 2013, p. 202.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 271–277.

- Miller 1959, p. 6.

- James 2014, pp. 186–209.

- Keogh 1965, p. 290.

- Miller 1959, pp. 272–273.

- Keogh 1965, p. 310.

- Johnston 2007, pp. 8–9.

- Keogh 1965, p. 298.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 336–337.

- Miller 1959, p. 270.

- Miller 1959, pp. 229–232 & 251–255.

- Miller 1959, pp. 222–225 & 273–274.

- Miller 1959, pp. 272–274.

- Morison 1975, pp. 370–371.

- Miller 1959, pp. 273–277.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 324.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 298.

- Miller 1959, p. 289.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 63.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 307.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 300–307.

- Miller 1959, pp. 290–293.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 300–301.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 32–33.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 303–312.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 36–37.

- Miller 1959, p. 280.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 38–39.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 357.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 328.

- Keogh 1965, p. 340.

- Miller 1959, p. 287.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 34.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 338–339.

- Hammel 2010, p. 155.

- Morison 1975, p. 383.

- Tanaka 1980, p. 114.

- Keogh 1965, p. 338.

- Morison 1975, p. 379.

- Miller 1959, p. 277.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 327–328.

- Morison 1975, p. 381.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 317.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 316.

- Miller 1959, p. 290.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 60.

- Odgers 1968, p. 128.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 32.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 350.

- Morison 1975, pp. 381–383.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 82.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 348.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 81–82.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 86.

- Tanaka 1980, p. 117.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 83–87.

- Miller 1959, pp. 290–291.

- Miller 1959, p. 293.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 349–350.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 350–351.

- Miller 1959, p. 291.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 352–355.

- Morison 1975, pp. 385–386.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 357–358.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 54.

- Miller 1959, p. 292.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 362.

- Hough & Crown 1952, Note 11, p. 70.

- Morison 1975, p. 387.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 353.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 361–362.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 71.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 364–365.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 74–75.

- Miller 1959, pp. 293–294.

- Morison 1975, p. 386.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 367–370.

- Hough & Crown 1952, Map p. 68.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 374–379.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 380.

- Rottman 2002, p. 190.

- Miller 1959, p. 294.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 389.

- Morison 1975, p. 388.

- Casey 1951, pp. 193–194.

- Mortensen 1950, pp. 342–343.

- Odgers 1968, pp. 200–201.

- Bureau of Yards and Docks 1947, p. 295.

- Tanaka 1980, p. 120.

- Casey 1951, pp. 194–196.

- Miller 1959, p. 295.

- Miller 1959, pp. 299–300.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 398.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 403.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 138–139.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 398–408.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 152.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 411.

- Rottman 2002, p. 192.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 429.

- Grant 2016, p. 225.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 408–412.

Bibliography

- Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area (1943). Terrain Study No. 63: Locality Study of Cape Gloucester (revised). Brisbane, Queensland: Monash University. OCLC 220852182.

- Bureau of Yards and Docks (1947). Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940–1946. Vol. II. US Government Printing Office. OCLC 816329866. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Casey, Hugh J., ed. (1951). Airfield and Base Development. Engineers of the Southwest Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 220327037.

- Grant, Lachlan (2016). "Campaigns in Aitape–Wewak". In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–231. ISBN 978-1-107-08346-2.

- Hammel, Eric (2010). Coral and Blood: The U.S. Marine Corps' Pacific Campaign. Pacifica, California: Pacifica Military History. ISBN 978-1-89098-815-9.

- Hough, Frank O.; Crown, John A. (1952). The Campaign on New Britain. OCLC 1283735.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - James, Karl (2013). "On Australia's Doorstep: Kokoda and Milne Bay". In Dean, Peter (ed.). Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–215. ISBN 978-1-10703-227-9.

- James, Karl (2014). "The 'Salamaua Magnet'". In Dean, Peter (ed.). Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–209. ISBN 978-1-107-03799-1.

- Johnston, Mark (2007). The Australian Army in World War II. Botley, Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-123-6.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower. OCLC 7185705.

- Miller, John Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. OCLC 63151382.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Morison, Samuel Eliot (1975) [1950]. Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. VI. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 21532278.

- Mortensen, Bernhardt L. (1950). "Rabaul and Cape Gloucester". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). The Pacific—Guadalcanal to Saipan (August 1942 to July 1944) (PDF). The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. IV. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 311–356. ISBN 978-0-912799-03-2. OCLC 9828710. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Vol. II (repr. ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 246580191.

- Rottman, Gordon (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-31331-395-0.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Isolation of Rabaul. OCLC 987396568.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.

External links

- Rickard, J. (24 April 2015). "Battle of Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943 – April 1944". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- "The fighting conditions during the Cape Gloucester campaign as remembered by Marine Sidney Phillips". Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.