Battle of Talasea

The Battle of Talasea (6–9 March 1944) was a battle fought in the Pacific theater of World War II between Japanese and Allied forces. Dubbed "Operation Appease" by the Allies, the battle was part of the wider Operations Dexterity and Cartwheel, and took place on the island of New Britain, Territory of New Guinea, in March 1944 as primarily US forces, with limited Australian support, carried out an amphibious landing to capture the Talasea area of the Willaumez Peninsula, as part of follow-up operations as the Japanese began withdrawing east towards Rabaul following heavy fighting around Cape Gloucester earlier in the year. The assault force consisted of a regimental combat team formed around the 5th Marines, which landed on the western coast of the Willaumez Peninsula, on the western side of a narrow isthmus near the Volupai Plantation. Following the initial landing, the Marines advanced east towards the emergency landing strip at Talasea on the opposite coast. Their advance south was stymied by a small group of Japanese defenders who prevented the US troops from advancing quickly enough to cut off the withdrawal of the Japanese force falling back from Cape Gloucester.

| Battle of Talasea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Pacific War | |||||||

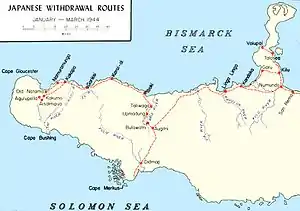

.jpg.webp) Map depicting the US Marine operation, March 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~3,000 | 596 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 17 killed and 114 wounded | 150 killed | ||||||

Prelude

Background

Japanese forces captured the island of New Britain in February 1942 after overwhelming the small Australian garrison stationed around Rabaul.[1] The Japanese subsequently built up a large garrison on the island, which became a lynchpin in the defensive barrier that they established following the failure of attempts to capture Port Moresby in late 1942. Actions around Cape Gloucester and Arawe – part of Operation Dexterity and the wider Operation Cartwheel – had been launched by the Allies to capture vital airfields and provide access through the sea passage between the straits separating New Britain from New Guinea, where during late 1943 the Allies had fought to secure the Huon Peninsula. In addition, the operations had sought to isolate the major Japanese base at Rabaul, as it had been decided that rather than destroying the base with a costly direct assault, a more prudent strategy would be to surround the base and therefore nullify it as a threat.[2] The 1st Marine Division's operations to secure Cape Gloucester would continue until April under the command of Major General William H. Rupertus. However, by early February US commanders were confident that their forces would prevail in securing western New Britain and they began planning to expand towards the east, advancing towards Talasea – which offered a low grade airstrip and a potential base – on the northern coast of the island, as part of actions to follow up the Japanese forces under Iwao Matsuda (Matsuda Force) who were withdrawing towards Cape Hoskins and Rabaul.[3][4]

The operation to secure the Talasea area of the Willaumez Peninsula was dubbed "Operation Appease" by the US planners. It would require an amphibious landing on a 350-yard (320 m) beach, dubbed "Red Beach" near the Volupai Plantation, on the northeastern side of the neck of the peninsula, which was bounded by a dense swamp to the north and a steep cliff to the south. The terrain south of Red Beach rose to the northern part of Little Mount Worri, which was in turn overlooked by Big Mount Worri to the south, while to the east, Mount Schleuther extended towards the coast, overlooking several villages. It was intended that landing would be followed by an advance to the southeast, towards Bitokara and Talasea with a follow-up drive south, and a landing on Garua to secure the Garua Plantation.[5]

Despite the limitations of the terrain on the flanks of the landing beach, to its front there were several redeeming features that offered tactical advantages for the troops undertaking the landing. The beach was situated along the narrowest part of the peninsula extending for a distance of 2.5 miles (4.0 km) east towards Garua Harbor, and had been identified as a likely landing zone by a former plantation owner, Flight Lieutenant Rodney Marshland, a Royal Australian Air Force officer; in this, it afforded a relatively flat and direct approach to the Marines' objectives, which were listed as the government buildings on the shore of Garua Harbor, the emergency landing ground at Talasea, and Garua Harbor.[6] In addition, the beach was serviced by a dirt track that offered the potential for vehicle access.[7]

Opposing forces

The main US force assigned to the operation was Combat Team A, a task organised regimental combat team, which consisted primarily of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Marines – under the command of Colonel Oliver P. Smith – supported by the 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines, a company from both the 1st and 17th Marines, and supporting elements including medical, armor, engineers, special weapons, ordnance, military police, and motor transport. Key supporting units included the 1st Medical Battalion, the 533rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, and the 1st Service Battalion.[8] The US force consisted of a little more than 3,000 ground troops, with the total force being around 5,000;[9] the majority of the landing craft were operated by the US Army engineers, with only a small number of US Navy vessels.[7]

The Japanese defending Talasea consisted of the 1st Battalion, 54th Infantry Regiment, a company from the 2nd Battalion, 54th Infantry Regiment, and a battery from the 23rd Field Artillery Regiment. In addition, there was a platoon of machine guns and a platoon of 90 mm mortars. The force totaled 596 men, of which 430 were in the immediate Talasea area.[10] These troops were drawn from Lieutenant General Yasushi Sakai’s 17th Division,[11] and were grouped together as "Terunuma Force", under the command of Captain Kiyamatsu Terunuma. These troops were tasked with the defending the area in order to secure a withdrawal route for the troops from Matsuda Force that were withdrawing from Cape Gloucester, in western New Britain.[12]

Battle

In the days prior to the assault, Royal Australian Air Force Bristol Beaufort aircraft flew numerous sorties from their base on Kiriwina softening up the defenses around the landing beach.[13] On 3 March, the landing was preceded by a small reconnaissance patrol, consisting of an Australian officer – Marshland – an American and two indigenous scouts, which was put ashore by PT boat. After determining contacting friendly local inhabitants and ascertaining the strength and dispositions of the Japanese in the vicinity, the patrol had departed the peninsula and returned to Iboki around midnight on 3 March by PT boat. The following couple of days were used for battle preparation, after which the US force set off for the overnight journey on, embarking from the 5th Marines' base at the Iboki Plantation at 13:00 on 5 March 1944 upon a fleet of 60 assorted types of landing craft escorted by five PT boats. On board one of the landing craft were four medium tanks.[7]

The following day, around first light, the landing was delayed almost half an hour as the fighter cover from the Fifth Air Force that had been assigned to support the landing failed to arrive; finally the order for the assault force to leave the line of departure was given by Smith despite the risks of proceeding without fighter cover. The initial assault force consisted of 500 marines from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines. These troops were tasked with securing a bridgehead through which follow on troops from the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines would pass as they pushed inland towards the Bitokara Mission.[14] Due to the presence of a coral reef offshore, the initial assault had to be made by two companies from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines aboard smaller tracked landing vehicles; these were lowered into the water from the larger tank landing craft, and as they made the run into the shore, they were provided covering machine gun fire from the tanks that were aboard one of the medium landing ships. This was answered by sporadic fire from the beach.[15]

As the two assault companies came ashore, a small spotter plane on an observation mission flew overhead, dropping grenades in lieu of the promised air support from the 5th Air Force. According to U.S. Marine Corps historians, Hough and Shaw, citing Lieutenant Colonel Isamu Murayama's Southeast Area Operations Record, this impromptu air support was later described by the defenders as heavy.[16] As the initial force pushed inland, several small scale clashes occurred, but the landing was largely unopposed. A beachhead was established about 200 yards (180 m) inland and patrols were sent out – on the right Company 'A' quickly met its objective, but on the left Company 'B' found the going a little harder due to swampy ground, which forced them to outflank it around the foothills of Lower Mount Worri where they encountered a small group of Japanese. To sea, the follow on waves were controlled by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Amory, in his own vessel, acting to ensure that the beach was not swamped by too many landing craft at the same time to ensure an orderly disembarkation as the 2nd Battalion followed up the 1st, moving through the beachhead towards Bitokara Mission. Nevertheless, the coral reefs slowed the boats coming in, forcing them to sail in single file, while the confines of landing beach made unloading slow and the requirement to manpack all equipment also added to the delays. Artillery landing on the water's edge suffered heavily from the Japanese mortars firing on the beach, while the medical staff on the beach also suffered heavily.[17][18]

Regardless, the advanced elements of the 2nd Battalion, consisting of its Company 'E', began moving through the 1st Battalion around 11:00 hours, even though the 1st had yet to secure the edge of the plantation. Of the four Sherman medium tanks that had come ashore, one became stuck on the beach, while the other three moved forward to support Company 'E' as it advanced along the track leading towards the plantation. Almost immediately they had an effect, silencing a Japanese machine gun position; however, one tank was damaged by Japanese infantry who swarmed around it in an effort to place magnetic mines on it. One succeeded, although he died in the act, and the tank was temporarily put out of commission, drawing off to the side of the track. The other two tanks continued on, supporting the infantrymen along with 81 mm mortar fire as they advanced against the southwest corner of the plantation. There, the Americans gained an intelligence boon when they recovered a map of the local Japanese defenses from the body of a Japanese officer who had been killed in the fighting. Subsequently, two companies from the 2nd Battalion – 'E' and 'G' – gained momentum: 'G' moving on the right of 'E', traversing the mountain slopes while 'E' moved along the track. By nightfall on the end of the first day, the Marines dug in.[19][20]

The Japanese commander, Terunuma, attempting to buy time for the Japanese forces withdrawing from Cape Gloucester, reinforced the troops attempting to hold Talasea, sending another company forward throughout the night of 6/7 March. In the darkness, they were able to advance to within 50 yards (46 m) of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines' positions. Nevertheless, these troops withdrew shortly after dawn when the Marines launched an early morning attack on 7 March. Throughout the day heavy fighting followed as the Americans advanced towards the opposite coast, sending patrols out towards the hills to the south in order to secure their flank. As they approached Mount Schleuther elements of the Japanese 54th Infantry Regiment, moving west along the high ground in an effort to cut the Marines off, began to pour heavy fire down on the Americans. In response, Company 'E' established a strong base of fire while Company 'F' – with covering fire from artillery and mortars – was hurriedly dispatched to gain a position from which to launch an attack by fire, with elements of Company 'H' protecting their right flank. Arriving ahead of the Japanese, the Marines began firing down on them, killing 40 in a one sided battle that pushed them down the reverse slope. Meanwhile, the US reinforcements – the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines – that had been scheduled to arrive early on 7 March were delayed until the afternoon, when they began taking over responsibility for the defense of the beachhead from the 1st Battalion. As a result, the plan for the envelopment of the village of Liapo, southwest of Little Mount Worri, and Waru, west of the emergency landing strip at Talasea, had to be modified. Instead of having one battalion proceed straight up the track while the crossed the mountains, a company from the 1st Battalion was sent through the scrub, west of the hills, towards Liapo. Hindered by the dense jungle they became isolated and had to harbor up for the night, while the 2nd Battalion established a night perimeter around part of Mount Schleuther and Bitokara track.[21][22]

Throughout the night, the Japanese in front of the 2nd Battalion's position began massing for an attack, but this was not carried out. On the morning of 8 March, Company 'F' launched an attack to their front, supported by a 37 mm gun and mortar fire; however, the attack quickly petered out when there was no answering fire from the Japanese. A patrol was subsequently sent out and found 12 dead Japanese. Later, a patrol was sent out towards Bitokara where they located a Japanese defensive position. The 2nd Battalion attempted to advance to contact, but again their efforts were thwarted by a hasty withdrawal by the Japanese defenders. When Company 'G' reached the eastern side of Bitokara, the remainder of the battalion joined them. The Americans then sent out several scouts to locate the Japanese positions on Mount Schleuther and around Talasea. They subsequently launched a fruitless attack on the peak which was beaten back by heavy fire, and resulted in 18 casualties amongst the Marines. As scouts reported the emergency landing strip at Talasea unoccupied, Company 'F' was dispatched to secure it and while the rest of the 2nd Battalion withdrew to Bitokara for the night, the lone company remained on the airstrip. Elsewhere, the remainder of the 1st Battalion moved towards Liapo to marry up with its isolated company, guided by a local scout. A friendly fire incident followed as the two forces joined up and mistook the guide for a Japanese soldier. After reorganizing and sending for another guide, the 1st Battalion set out for Waru. Held up by difficult terrain, they harbored up for the night.[23][24]

Heavy artillery and mortar fire was exchanged by both sides throughout the night, but it slackened as the Japanese defenders slowly slipped away south towards Bola, having been given the order to withdraw from their divisional headquarters, leaving a small rearguard of 100 soldiers to delay the US troops throughout 9 March. The Marines attacked Waru the following morning, but found the main Japanese positions abandoned, although they managed to capture two soldiers who had been too slow to get away. Later, a patrol was sent through to contact Company 'F' while another was sent across Garua Harbor aboard two landing craft to find it also devoid of Japanese. Following this, the 5th Marines began mopping up operations.[25] Supply craft were then redirected to Talasea, while the Japanese rearguard withdrew to Garilli, 4 miles (6.4 km) south, where they established another defensive line, having successfully delayed the Marines long enough to prevent them from cutting Matsuda Force's withdrawal route.[26]

Aftermath

The battle cost the Americans 17 killed and 114 wounded, while 150 Japanese are estimated to have been killed.[25] In the days following the landing, the Americans continued patrolling actions to follow up the withdrawing Japanese and secure Talasea, pushing north around the bay towards Pangalu, across the neck of the peninsula to Liapo and Volupai and on to Wogankai, southwest to Garu opposite Cape Bastian, and southwards along the coast towards Stettin Bay. As a result of the action, the US forces established themselves in a position to further harass the Japanese forces that were withdrawing east to Cape Hoskins. The commander of the 5th Marines, Smith, also recommended that a forward naval base be established at Talasea for PT boats to operate from in order to interdict the barges that the Japanese were sending between Cape Hoskins and Rabaul.[27]

In conjunction with the eastern expansion towards Talasea on the northern coast, the US forces had planned to advance towards Gasmata on the southern coast, where they would hold a line between Talasea and Gasmata, in an effort to isolate the main Japanese base around Rabaul. Responsibility for taking Gasmata was to have been given to the 126th Infantry Regiment, assigned to the 32nd Infantry Division;[28] however, the advance to Gasmata was eventually cancelled,[29] when US planners realized that it was geographically unsuited.[30] In this regard, concerns were raised about the swampy ground – which made it unsuitable for airfield construction – and the possibility of attack from the Japanese strong hold at Rabaul, particularly during the landing operation during which the landing ships would be particularly vulnerable.[31]

Following the capture of Talasea, the US advance east essentially ceased, except for limited patrols in the weeks following the capture of Talasea airfield. In April, the US Army 40th Infantry Division, arriving from Guadalcanal,[32] replaced the 1st Marine Division, which had lost a total 310 killed and 1,083 wounded up to that point in the entire campaign; against this the Japanese recorded 3,868 of their own as killed in action. Limited fighting followed as the 40th Infantry Division secured Hoskins Plantation and the abandoned airfield there on 7 May, but after this there was a lull in the fighting on New Britain as the US forces kept largely to the western end of the island, while the Japanese held Rabaul, on the Gazelle Peninsula. In the middle, Australian-led indigenous troops of the Allied Intelligence Bureau continued small-scale operations.[33] These would last until the Australian 5th Infantry Division, under Major General Alan Ramsay, arrived in October–November 1944, when the 40th Infantry were relieved. The Australians subsequently began a limited offensive, landing at Jacquinot Bay and then pushing further east on both the northern and southern coasts, but eventually the Australians also sought to conduct a campaign of containment rather than destruction, after occupying a line between Wide Bay and Open Bay.[31]

References

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 392–441.

- Miller 1959, p. 272.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 152.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 411.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 414–417.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 413.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 153.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 153–154.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 416–417.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 417.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 155.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 412.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 416.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 154–156.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 414–418.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 156.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 156–159.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 418–421.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 158.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 420.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 421–422.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 160–161.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 422–423.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 162–163.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 164.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 424–425.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 164–171.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 12–15.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 74.

- Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 15–18.

- Rickard 2015.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 429.

- Hough & Crown 1952, p. 187.

Bibliography

- Hough, Frank O.; Crown, John A. (1952). The Campaign on New Britain. Archived from the original on 24 December 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Miller, John Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Rickard, J. (2015). "Operation Dexterity – New Britain Campaign, 16 December 1943 – 9 March 1944". History of War. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Vol. Series IV—Army. Volume (1st ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219.