Nagarjunakonda

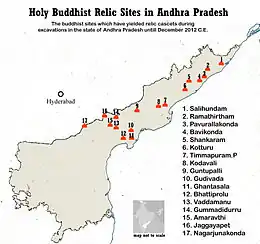

Nagarjunakonda: Nāgārjunikoṇḍa, meaning Nagarjuna Hill) is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Palnadu district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh.[2][3] It is one of India's richest Buddhist sites, and now lies almost entirely under the lake created by the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam. With the construction of the dam, the archaeological relics at Nagarjunakonda were submerged, and had to be excavated and transferred to higher land, which has become an island.

| Nagarjuna Konda | |

|---|---|

Ruins of the site | |

| Location | Macherla mandal, Palnadu district, Andhra Pradesh, India |

| Coordinates | 16°31′18.82″N 79°14′34.26″E |

| Governing body | Archaeological Survey of India |

Location of Nagarjuna Konda in India | |

.jpg.webp)

The site was once the location of a large Buddhist monastic university complex, attracting students from as far as China, Gandhara, Bengal and Sri Lanka. There are ruins of several Mahayana Buddhist and Hindu shrines.[4] It is 160 km west of another important historic site, the Amaravati Stupa. The sculptures found at Nagarjunakonda are now mostly removed to various museums in India and abroad. They represent the second most important group in the distinctive "Amaravati style", sometimes called "Later Andhra".[5] There is also a palace area, with secular reliefs, that are very rare from such an early date, and show Roman influence.[6]

The modern name is after Nagarjuna, a southern Indian master of Mahayana Buddhism who lived in the 2nd century, who was once believed, probably wrongly, to have been responsible for the development of the site. The original name, used when the site was most active, was "Vijayapuri".

This Nāgārjunakoṇḍa (sometimes Nāgārjunikoṇḍa) site in Andhra Pradesh is not to be confused with the Nāgārjuna (or Nāgārjuni) caves near the Barabar Caves in Bihar.

History

Coins issued by the later Satavahana kings (including Gautamiputra Satakarni, Pulumavi, and Yajna Satakarni) have been discovered at Nagarjunakonda.[7] An inscription of Gautamiputra Vijaya Satakarni, dated to his 6th regnal year, has also been discovered at the site, and proves that Buddhism had spread in the region by this time.[8]

The site rose to prominence after the decline of the Satavahanas, in the first quarter of the 3rd century, when the Ikshvaku king Vashishthiputra Chamamula established his capital Vijayapuri here. The coins and inscriptions discovered at Nagarjunakonda name four kings of the Ikshavaku dynasty: Vashishthi-putra Chamtamula, Mathari-putra Vira-purusha-datta, Vashishthi-putra Ehuvala Chamtamula, and Vashishthi-putra Rudra-purusha-datta. An inscription dated to the 30th regnal year of the Abhira king Vashishthi-putra Vasusena has also been discovered at the ruined Ashtab-huja-svamin temple.[8] This has led to speculation that the Abhiras, who ruled the region around Nashik, invaded and occupied the Ikshavaku kingdom. However, this cannot be said with certainty.[9]

The Ikshavaku kings constructed several temples dedicated to the deities such as Sarva-deva, Pushpabhadra, Karttikeya, and Shiva. Their queens, as well as Buddhist upasikas such as Bodhishri and Chandrashri, constructed several Buddhist monuments at the site.[10] It is believed that Sadvaha authorised the first monastic construction at Nagarjunakonda. During the early centuries, the site housed more than 30 Buddhist viharas; excavations have yielded art works and inscriptions of great significance for the scholarly study of the history of this early period.[11]

The last extant Ikshavaku inscription is dated to the 11th year (c. 309 CE) of Rudra-purusha: the subsequent fate of the dynasty is not known, but it is possible that the Pallavas conquered their territory by the 4th century.[12] The site declined after the fall of the Ikshavaku power. Some brick shrines were constructed in the Krishna River valley between 7th and 12th centuries, when the region was controlled by the Chalukyas of Vengi. Later, the site formed the part of the Kakatiya kingdom and the Delhi Sultanate. During the 15th and the 16th centuries, Nagarjunakonda once again became an important site. The contemporary texts and inscriptions allude to a hill fortress at Nagarjunakonda, which was probably built by the Reddi rulers as a frontier fortress protecting their main fort of Kondaveedu. It later appears to have come under the control of the Gajapatis: a 1491 CE inscription dated to the reign of the Gajapati king Purushottama indicates that the Nagarjunakonda fortress was controlled by his subordinate Sriratharaja Shingarayya Mahapatra. In 1515, the Vijayanagara king Krishnadevaraya stormed the fortress during his invasion of the Gajapati kingdom.[13]

The region was later ruled by the Qutb Shahi dynasty and the Mughals. It was subsequently granted as an agrahara to the pontiff of the Pushpagiri Math.[8]

Archaeological research

In 1926, a local schoolteacher, Suraparaju Venkataramaih, saw an ancient pillar at the site, and reported his discovery to the Madras Presidency government. Subsequently, Shri Sarasvati, the Telugu language Assistant to the Archaeological Superintendent for Epigraphy of Madras, visited the site, and it was recognized as a potential archaeological site.[14]

The first discoveries were made in 1926 by French archaeologist Gabriel Jouveau-Dubreuil (1885–1945).[15] Systematic digging was organized by English archaeologists under A. H. Longhurst during 1927–1931. The team excavated the ruins of several Buddhist stupas and chaityas, as well as other monuments and sculptures.[15][14]

In 1938, T N Ramachandran led another excavation at the site, resulting in the discovery of some more monuments. In 1954, when the construction of the proposed Nagarjuna Sagar Dam threatened the site with submergence, a large-scale excavation led by R Subrahmanyam was started to salvage the archaeological material. The excavation, conducted during 1954-1960, resulted in the discovery of a number of relics, dating from the Early Stone Age to the 16th century. Later, around 14 large replicas of the excavated ruins and a museum were established on the Nagarjunakonda hill. Some of the sculptures excavated at Nagarjunakonda are now at other museums in Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata, Paris and New York.[14]

An archaeological catastrophe struck in 1960, when an irrigation dam was constructed across the nearby Krishna River, submerging the original site under the waters of a reservoir. In advance of the flooding, several monuments were dug up and relocated to the top of Nagarjuna's Hill, where a museum was built in 1966 Other monuments were relocated to the mainland, east of the flooded area. Dedicated archaeologists managed to recover almost all of the relics.

Buddhist ruins

Archaeological inscriptions at the site show that the Andhra Ikshvaku kings Virapurusadatta, Ehuvula and family members patronized Buddhism. The inscriptions also show state-sponsorship of construction of temples and monasteries, through the funding of the Ikshvaku queens. Camtisiri in particular, is recorded as having funded the building of the main stupa for ten consecutive years. The support also spread beyond the noble classes, many non-royal names being inscribed in the relics. At its peak, there were more than thirty monasteries and it was the largest Buddhist centre in South India. Inscriptions showed that there were monasteries belonging to the Bahuśrutīya and Aparamahavinaseliya sub-schools of the Mahāsāṃghika, the Mahisasaka, and the Mahaviharavasin, from Sri Lanka. The architecture of the area reflects that of these traditions. There were other monasteries for Buddhist scholars originating from the Tamil kingdoms, Orissa, Kalinga, Gandhara, Bengal, Ceylon (the Culadhammagiri) and China. There is also a footprint at the site of the Mahaviharavasin monastery, which is believed to be a reproduction of that of Gautama Buddha.

The great stupa at Nagarjunakonda belongs to the class of uncased stupas, its brickwork being plastered over and the stupa decorated by a large garland-ornament.[2] The original stupa was renovated by the Ikshvaku princess Chamtisiri in the 3rd century, when ayaka-pillars of stone were erected. The outer railing, if any, was of wood, its uprights erected over a brick plinth. The stupa, 32.3 m in diameter, rose to a height of 18 m with a 4 m wide circumambulatory. The medhi stood 1.5 m and the ayaka-platforms were rectangular offsets measuring 6.7 by 1.5 m.[18]

The style of the reliefs recovered is "all but indistinguishable" from those of the final phase of the Amaravati Stupa not very far away, from the second quarter of the third century, slightly earlier than Nagarjunakonda. Though "lively and interesting", they show "a great decline since the mature phase at Amaravarti", with less complex groupings, various mannerisms in the figures, and a flatness to the surfaces.[19]

Hindu ruins

Most of the Hindu ruins at Nagarjunakonda can be identified as Shaivite, wherever an identification is possible. One of the temples has an inscription naming the god as "Mahadeva Pushpabhadraswami" (Shiva). Stone images of Kartikeya (Murugan) were found at two other shrines. An inscription found at another excavated shrine refers to yet another Shiva shrine. At least one temple, attested by a 278 CE inscription, can be identified as Vaishnavite, based on the image of an eight-armed god. A large sculpture of Devi has also been discovered at the site.[4]

Greco-Roman artifacts

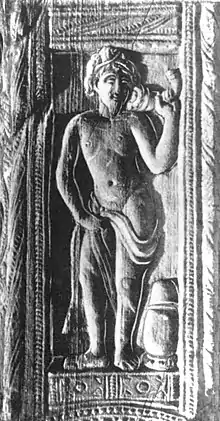

Various remains suggesting Greco-Roman influence can be found at Nagajurnakonda.[16] Roman coins were found, in particular Roman Aurei, one of Tiberius (16-37 CE), and the other of Faustina the Elder (141 CE), as well as a coin of Antoninus Pius.[20][16] These finds seem to attest to trade relations with the Roman world.[21] A relief representing Dionysus was also found in the Nagarjunakonda Palace site. He has a light beard, is semi-nude and carries a drinking horn, and there is a barrel of wine next to him.[16]

- Scythian influence

Indo-Scythians also appear, with reliefs of Scythian soldiers wearing caps and coats.[22][23] According to an inscription in Nagarjunakonda, a garrison of Scythian guards employed by the Iksvakus Kings may also have been stationed there.[25]

Inscriptions

The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions are a series of epigraphical inscriptions found in the area of Nagarjunakonda. The inscriptions are associated with the blossoming of Buddhist structures and the rule of the Ikshvaku, in the period covering approximately 210-325 CE.[26]

The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions tends to stress the cosmopolitan nature of Buddhist activities there, explained that a variety of Buddhist monks came from various lands.[26] An inscription in a monastery (Site No.38) describes its residents as acaryas and theriyas of the Vibhajyavada school, "who had gladdened the heart of the people of Kasmira, Gamdhara, Yavana, Vanavasa[27] and Tambapamnidipa".[26] The inscriptions suggest the involvement of these various people with Buddhism.[28]

The inscriptions are either in Prakrit, in Sanskrit, or a mix of both, and are all in the Brahmi script.[26] The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions are the earliest substantial South Indian Sanskrit inscriptions, probably from the late 3rd-century to early 4th-century CE. These inscriptions are related to Buddhism and to the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism, and parts of them reflect both standard Sanskrit and hybridized Sanskrit.[29]

The spread of the usage of Sanskrit inscriptions to the south can probably be attributed to the influence of the Western Satraps who promoted the usage of Sanskrit in epigraphy, and who were in close relation with southern Indian rulers: according to Salomon "a Nagarjunakonda memorial pillar inscription of the time of King Rudrapurusadatta attests to a marital alliance between the Western Ksatrapas and the Iksvaku rulers of Nagarjunakonda".[30][31] According to one of the inscriptions, Iksvaku king Virapurushadatta (250-275 CE) had multiple wives,[32] including Rudradhara-bhattarika, the daughter of the ruler of Ujjain (Uj(e)nika mahara(ja) balika), possibly the Indo-Scythian Western Kshatrapa king Rudrasena II.[33][34][35]

Etymology

The modern name of the site originates from its presumptive association with the Buddhist scholar Nagarjuna (konda is the Telugu word for "hill"). However, the archaeological finds at the site do not prove that it was associated with Nagarjuna. The 3rd–4th-century inscriptions discovered there make it clear that it was known as "Vijayapuri" in the ancient period: the name "Nagarjunakonda" dates from the medieval period. The Ikshavaku inscriptions invariably associate their capital Vijayapuri with the Sriparvata hill, mentioning it as Siriparvate Vijayapure.[36]

Fa-Hien, in his travelogue A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms, mentions a five storey monastery on top of the hill, dedicated to Kassapa Buddha. He describes each storey as being in the shape of a different animal, with the uppermost being in the shape of a pigeon.[37] Fa-Hien refers to the monastery as Po-lo-yue; which has been interpreted to mean Pārāvata, meaning "pigeon" (hence the name "Pigeon Monastery"), or Parvata, meaning "hill" in Sanskrit (although the latter is considered to be the correct name).[38]

When Hiuen-Tsang travelled to Andhradesa c. 640 CE,[39] he also visited this place. He has referred to Parvata as Po-lo-mo-lo-ki-li [40] or "Mountain of the Black Bee" in his book Great Tang Records on the Western Regions; as it was then known as Bhramaragiri[41] (bhramara means "bee", giri means "hill" or "mountain" in Sanskrit), because it had a shrine of Bharmaramba (a form of goddess Durga).[42] However, many scholars believe that Po-lo-mo-lo-ki-li was actually Parimalagiri alias Gandhagiri (Gandhamardan hills) in Odisha.[43]

Nagarjunasagar Dam

The Nagarjunasagar Dam is the tallest masonry dam in the world, constructed between 1955 and 1967. The excavated remains of the Buddhist civilisation were reconstructed and preserved at a museum on the island situated in the midst of the man-made Nagarjunasagar Lake The site has a 14th-century fort, medieval temples and a museum constructed like a Buddhist vihara. The museum houses a collection of relics of Buddhist culture and art These include a small tooth and an ear-ring believed to be that of Gautama Buddha. The main stupa of Nagarjunakonda named Mahachaitya is believed to contain the sacred relics of the Buddha. A partly ruined monolithic statue of the Buddha is the main attraction at the museum. It also houses historic finds in the form of tools from Paleolithic and Neolithic times, as well as friezes, coins and jewellery.[44][45]

Tourism

Located in the Guntur district, Nagarjunakonda Island is not directly accessible on the State Highway. The nearest train station is at Macherla, 29 km away. The island is mainly connected by a ferry to the mainland. The area is also known for panoramic views of the valley from a viewing area near the dam, and is also the site of the Ethipothala Falls, a natural waterfall that cascades down 22 m into a blue lagoon that is also a breeding centre for crocodiles. The nearby Srisailam wildlife sanctuary and the Nagarjunsagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve are refuge for diverse reptiles, birds and animals. Srisailam, which sits on the shore of Krishna in the Nallamala Hills is a site of immense historical and religious significance, including a Shiva temple that is one of the 12 sacred Jyotirlingas.

References

- [https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/38238 MET museum page

- Longhurst, A. H. (October 1932). "The Great Stupa at Nagarjunakonda in Southern India". The Indian Antiquary. ntu.edu.tw. pp. 186–192. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Syamsundar, V. L. (13 February 2017). "Palnadu aspires for separate district status". www.thehansindia.com. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- T. Richard Blurton (1993). Hindu Art. Harvard University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-674-39189-5.

- Rowland, pp. 209-214

- Rowland, 212

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, pp. 2–3.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 3.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 4.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 10.

- "Ancient India". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, pp. 8–9.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 9.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 2.

- The Buddhist Antiquities of Nagarjunakonda, Madras Presidency by A. H. Longhurst. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 72, Issue 2–3 June 1940 , pp. 226–227

- Varadpande, M. L. (1981). Ancient Indian And Indo-Greek Theatre. Abhinav Publications. pp. 91–93. ISBN 9788170171478.

- Carter, Martha L. (1968). "Dionysiac Aspects of Kushān Art". Ars Orientalis. 7: 121–146, Fig. 15. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 4629244.

- Visit Lord Budha – Nagarjunakonda Archived 4 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Harle, 38

- Turner, Paula J. (2016). Roman Coins from India. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9781315420684.

- Dutt, Sukumar (1988). Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India: Their History and Their Contribution to Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 132. ISBN 9788120804982.

- "In Nagarjunakonda Scythian influence is noticed and the cap and coat of a soldier on a pillar may be cited as an example.", in Sivaramamurti, C. (1961). Indian Sculpture. Allied Publishers. p. 51.

- "A Scythian dvarapala standing wearing his typical draperies, boots and head dress. Distinct ethnic and sartorial characteristics are noteworthy.", in Ray, Amita (1982). Life and Art of Early Andhradesa. Agam. p. 249.

- "National Portal and Digital Repository: Record Details". museumsofindia.gov.in.

- "The Iksvakus Kings employed Scythian soldiers as their palace guards, and also an inscription hints that a colony of Scythians existed at Nagarjunakonda.", in The Journal of the Institution of Surveyors (India). Institution of Surveyors. 1967. p. 374.

- Singh, Upinder (2016). The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology. SAGE Publications India. pp. 45–55. ISBN 9789351506478.

- Longhurst, A. H. (1932). The Great Stupa at Nagarjunakonda in Southern India. The Indian Antiquary. p. 186.

- Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2002). Tribal Roots of Hinduism. Sarup & Sons. p. 311. ISBN 9788176252997.

- Salomon 1998, pp. 90–91.

- Salomon 1998, pp. 93–94.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1986). Vakataka - Gupta Age Circa 200-550 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 66. ISBN 9788120800267.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 5.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 6.

- "Another queen of Virapurusha was Rudradhara-bhattarika. According to D.C. Sircar she might have been related to Rudrasena II (c. a.d. 254-74) the Saka ruler of Western India" in Rao, P. Raghunadha (1993). Ancient and medieval history of Andhra Pradesh. Sterling Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 9788120714953.

- (India), Madhya Pradesh (1982). Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Ujjain. Government Central Press. p. 26.

- K. Krishna Murthy 1977, p. 1.

- Legge, James (1971). Travels of Fa-Hien.

- Barua, Dipak Kumar (1969). Viharas In Ancient India.

- "Xuan Zang stayed in Vijayawada to study Buddhist scriptures". The Hindu. 3 November 2016. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Subrahmaniam, K.R. (1937). Journal Of The Andhra Historical Research Society,vol.10,pt.1 To 4. pp. 100–101.

- Samuel Beal (1911). Life Of Hiuen Tsiang By The Shaman Hwui Li.

- Beal, S. (1887). "Some Remarks on the Narrative of Fâ-hien". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 19 (2): 191–206. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00019389. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25208860. S2CID 162362496.

- Donaldson, Thomas E. (2001). Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa: Text. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6.

- "city information of hyderabad, nagarjunasagar, nagarjunakonda, warangal, medak". 14 May 2009. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Tourism of India - Buddha - Excursion". 21 December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

Bibliography

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- K. Krishna Murthy (1977). Nāgārjunakoṇḍā: A Cultural Study. Concept Publishing Company. OCLC 4541213.

- Archaeological Survey of India (1987). Nagarjunakonda.

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, pp. 209-214, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509984-2.