Moray Estate

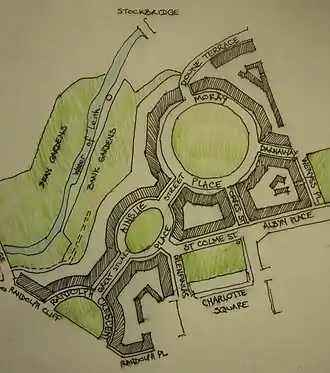

The Moray Estate in Edinburgh was an exclusive early 19th century building venture attaching the west side of Edinburgh's New Town.

Built on an awkward and steeply sloping site, it has been described as a masterpiece of urban planning.[1]

Background

The ground, extending to 5.3 hectares, was acquired in 1782 by the 9th Earl of Moray from the Heriot Trust.[2] The land contained Drumsheugh House, Moray House and its service block, and large gardens lying between Charlotte Square and the Water of Leith.

In 1822 his son, Francis Stuart, 10th Earl of Moray, commissioned the architect James Gillespie (later known as James Gillespie Graham after marriage into the wealthy Graham family) to draw up plans to build over 150 huge townhouses on the land. The houses were set on large plots, even by surrounding New Town standards, and were complemented by a series of private gardens, most notably on the slopes of the Water of Leith.

The scheme was curtailed on its south side due to the proposed new road and bridge (suggested and partly funded by John Learmonth who owned lands on the west bank of the Water of Leith), which culminated in the construction of Dean Bridge 1829/31. Land south of this road line, including the Drumsheugh House section, were not developed until later (parcelled with other lands in the West End).

Sales were begun (from plan) by auction on 7 August 1822. Over and above the cost of the plot, purchasers agreed to a build cost of £2000 to £3000 (depending on the plot) and an annual fee of £30. A "penalty clause" also imposed a fine of £100 on buildings not completed within 30 months. If comparing these prices to the norm, even for the affluent New Town this was perhaps ten times more than might have been expected. While the houses were among the largest ever built, this clearly guaranteed an exclusivity from the outset.[3]

While the majority of plots sold well and quickly (some of the corner plots were less popular, mostly being completed in the 1850s) the scheme as a whole was completed in 1858. The final phase included a central section on Great Stuart Street on the east side between Ainslie Place and Randolph Place, and the two corner blocks on Ainslie Place flanking the access to St Colme Street/Albyn Place.[4]

As one of the most affluent areas in Edinburgh, it set a trend. Glazing was changed to one-over-one format over almost the entire estate by 1950, but when architectural conservation came to the fore in the 1970's, it was one of the first areas to almost wholly restore windows to their original form.

Most basements throughout the estate are now separate properties and many of the blocks are divided into flats.

The entire scheme was designed as a residential enclave with the exception of Wemyss Place, which had ground floor commercial properties and a church in its centre. This church, by John Thomas Rochead does not look like a church and blends very well with the street. It was originally St Stephen's Free Church created in 1847 for Rev Gillies. Whilst intended as residential many properties became commercial through the years and by the 1970s these commercial uses exceeded 50%. This has reversed in recent years.

The street lights were originally individual tallow lamps. A unified gas lighting design and system was introduced by John Kippen Watson in the 1860s and this was converted to electric around 1910. However, the original lamps were mainly removed and replaced by modern lamp-posts in the 1960s. Edinburgh's New Town Conservation Area Committee restored electric versions of the original lamps in the 1980s and these are highly appropriate in appearance. For some reason Forres Street was omitted from this upgrade and that street still has two 1960s lamp-posts.

Form

The general form of the estate is as four storey and basement houses, set back behind the front basement area, and with a private garden to the rear. The continuous form necessitates a different solution on the corner blocks: these generally have a ground floor and basement duplex unit accessed from the more important street and flats above accessed from the secondary street. These either have no garden or a detached garden. From the pavement a flight of steps gives independent access to the basement, generally a service area. A short flight of steps rise to the main entrance, usually supported on a stone arch.

The buildings are constructed of local Craigleith sandstone with roofs of Scots slate with lead flashings.[5]

The typical interior has a grand open staircase built in stone topped by an ornate cupola giving it daylight, and often embellished with ornate plasterwork. The main room for public entertainment was usually the first floor front room.

Gardens

.jpg.webp)

The gardens form part of the collection of New Town Gardens. The Bank Gardens between the estate and the Water of Leith extend to 4.1 acres and slope steeply and were raised further to level the estate. A virtually inevitable landslip occurred at the back of the Ainslie Place feus in 1825 and had to be rectified by the addition of structural arches by James Jardine. A further landslip in the south-west corner in 1837 required further arches and these were then re-invented as a high level walkway leading to Dean Bridge. However the southern section of the Bank Gardens did not become fully operational until 1840.[2]

Over and above the Bank Gardens two other substantial private gardens were created: Moray Place Gardens and Ainslie Place Gardens. Of these Moray Place Gardens is sufficiently large and sufficiently screened to provide picnic areas and croquet lawns.

The several garden areas remain the private joint property of the Moray Estate owners (often called the Moray Feuars).

The pavements around the gardens are of "horonised" form. This is created from a series of vertical slivers of granite, created by the squaring of the granite setts on the vehicle surface, thereby making full use of the material.

Mews

The Moray estate (due to its layout concept) is the only set of New Town buildings which do not have ancillary mews to the rear. Instead the mews were located remotely: on Gloucester Lane and on Randolph Lane. The mews are fewer in number than would be expected for the number of houses on the estate.

Moray Place

Appearing as a circle but actually a duodecagon this is the largest and grandest space within the plan. Technically it is symmetrical around its northwest/southeast axis, but the scale of the form and central gardens makes this impossible to interpret on the ground, and this is only visible from above. Although rear mews were standard at the time of building, the layout did not allow this (the nearest are on Gloucester Lane).

Lord Moray took one of the largest and most prominent houses: 28 Moray Place. Other notable residents included Alexander Kinnear, 1st Baron Kinnear (2), George Deas, Lord Deas (3), Sir David Baxter of Kilmaron (5), Charles Dundas Lawrie (5), John Learmonth (6), John Sinclair, 1st Baron Pentland (6), Charles Hope, Lord Granton (12), Robert MacFarlane, Lord Ormidale and his son George Lewis MacFarlane (14), John MacGregor McCandlish (18), John Hope, Lord Hope (20), Francis Brown Douglas (Lord Provost) (21), Bouverie Francis Primrose (22), Francis Jeffrey, Lord Jeffrey (24), George Young, Lord Young (28), Andrew Coventry and his son George Coventry FRSE (29), Thomas Charles Hope (31), John Hope (31), Sir James Miles Riddell (33), John Fullerton, Lord Fullerton (33), Baron Hume (34), Robert Kerr, Lord Kerr (38), Robert Christison and his sons Sir Alexander Christison and David Christison (40), William Thomas Thomson and his son Spencer Campbell Thomson (41), Thomas Jamieson Boyd (Lord Provost) (41), James Skene (46), Sir James Wellwood Moncreiff, 9th Baronet (47), John Corse Scott (48), James Buchanan (1785-1857) and Rev George Coventry (49)[6]

Ainslie Place

Named after the Earl's wife, Margaret Jane Ainslie, daughter of Col. Sir Philip Ainslie of Pilton, Ainslie Place stands in the centre of the scheme. The format is an oval circus laid on a south-west to north-east axis, between the two halves of Great Stuart Street.

The scheme has always been popular with Scottish law lords and eminent physicians. Notable residents include John Millar, Lord Craighill (2), William Blackwood (3), Edward Maitland, Lord Barcaple (3), John MacWhirter (physician) (4), John Cowan, Lord Cowan (4), Mark Napier (historian) (6), Reginald Fairlie (office at 7), John Duncan (surgeon) (8), Alexander Bruce (neurologist) (8), James Ivory, Lord Ivory (9), Sir Thomas Dawson Brodie WS (9), James Gregory and his eminent sons Donald, William, Duncan and James all at 10, Sir William Edmonstone (11), George Cranstoun, Lord Corehouse (12), John Hay Forbes, Lord Medwyn (17), James Spence (surgeon) and George Burnett, Lord Lyon (21), Neil Kennedy, Lord Kennedy (22), Francis Cadell (artist) and his actress sister Jean Cadell (22), John Rankine (legal author) (23), Dean Edward Ramsay and his brother Admiral Sir William Ramsay (23) in later life (see Darnaway St), Very Rev James Robertson (25)

Randolph Crescent

This street forms the entrance into the estate from the south. Randolph Crescent Garden was originally retained by Lord Moray and Graham's plan showed a large mansion in the centre, probably as a replacement to Drumsheugh House. It was ultimately decided this was not a good location to build.[3]

The elevated ground level in the central garden may be the original ground level or may be due to the placing of excess soil here during original construction. It facilitated a large air raid shelter being constructed here during the Second World War.[7]

Notable residents include Edward Gordon, Baron Gordon of Drumearn (2), William Mackintosh, Lord Kyllachy (6), Robert Smith Candlish (9), Erskine Douglas Sandford (11), William Campbell, Lord Skerrington (12), and James Stevenson and his daughters Flora and Louisa (13).

Randolph Cliff

The dramatic entrance to the Moray Estate from Dean Bridge begins with Randolph Cliff, which stands dramatically over the Water of Leith far below. It was one of the final sections to be completed (and quite an engineering feat) and is laid out as flats rather than houses. The corner block as a complex stair to access the main stair, unlike any other block on the estate.

Randolph Place

Somewhat detached from the rest of the estate, Randolph Place never had the same allure for housing and from the outset seems to have attracted office use. This may be because the rear of West Register House was never developed to the same standard as the front creating a less attractive setting. Robert Adam's original plan for the building included a grand rear entrance onto Randolph Place. However when the funds could not be found for Adam's design, architect Robert Reid was called in to modify the plan. The modified plan placed attenuated pavilions flanking a Diocletian window above a Venetian window at the rear of the building overlooking Randolph Place, and although architect David Bryce later drew up plans to add towers to the pavilions, this work was never carried out.[8][9] Randolph Place therefore became a comparatively unimpressive entrance from the West End's Melville Street, into Charlotte Square and on to George Street. City of Edinburgh Council have undertaken a number of public consultations on possible ways to improve Randolph Place in recent years, including potentially resurfacing it or the addition of green space and public art, and the possibility of a cycle route from Melville Street, to George Street via Randolph Place, but as of 2022 nothing has been agreed.[10][11]

Two famous architects had their offices here: Alexander Hunter Crawford at 10 and Reginald Fairlie at 14.[12]

Great Stuart Street

Split into two halves by Ainslie Place, this street is named after the Earl's family name of Stuart and his additional title of Baron Stuart (granted in 1796). It forms the links between the main sections of the estate. It is the only north-south street in the New Town which numbers from the north (probably because building began at the north end).

Notable residents include Dr Alexander Monro (1), Sir Robert Christison (3), Harold Stiles (9), John Murray, Lord Murray (11), Lt Gen Thomas Robert Swinburne (13), William Henry Fox Talbot (13), James Warburton Begbie (16), William Edmonstoune Aytoun (16) and William Henry Playfair (17).

Doune Terrace

Named after the Earl's country estate of Doune and family title (from 1581) of Lord Doune, this street links Moray Place to the lower streets around Stockbridge.

Notable residents include James Craufurd, Lord Ardmillan (2) and Thomas Balfour, James Kinnear and James Pitman, Lord Pitman (9) .

St Colme Street

This street is named after the family title of Lord St Colme (granted in 1611) and links Ainslie Place to Queen Street.

Notable residents include George Angus (architect) (1), Thomas Guthrie Wright (6), Helen Kerr (6), and Andrew Rutherfurd, Lord Rutherfurd (9).

Harold Tarbolton had his office at no.4 and was later joined by Matthew Ochterlony.

Lord Rutherfurd employed William Notman to remodel his building in 1835, soon after it was built.

Albyn Place

Named after Glen Albyn on the Aberdeenshire estates, this short section is a continuation of St Colme Street linking to Queen Street.

Notable residents include William Forbes Skene founded Skene Edwards WS (offices at 5), Aeneas James George Mackay (7), David Mure, Lord Mure (8), Alan Campbell-Swinton (9), Prof Thomas Stewart Traill (10), Prof David Low (11)

Darnaway Street

Named after the family seat of Darnaway Castle, this short street links Moray Place to Heriot Row, then and still an exclusive Edinburgh address.

Notable residents include Thomas Duncan (painter) (1), William Kirk Dickson (3), George Joseph Bell (6), Edward Ramsay (7), Archibald Campbell Swinton and his son George Swinton (7), James Buchanan (1785-1857) (8), John Steell (11) and Robert Matthew (12).

Current residents include Prof Peter Higgs.[13]

Forres Street

Named after the family estate of Forres, this street connects Moray Place to Charlotte Square.

Notable residents include Thomas de Quincey (1), Thomas Chalmers (3), Robert Omond (4), John Montgomerie Bell (4), Ramsay Traquair (4), Sir Alexander Kinloch (5), David Paulin (6) and Archibald Fleming (9), James Maidment (10) Schomberg Scott (office) (11).

Glenfinlas Street

Named after the family rural estate of Glenfinlas in the Trossachs, this short street formed the north-west connection to Charlotte Square and appears a completion of the square. Due to boundary/ownership issues between the Moray Estate and Charlotte Square the final block was not completed until the late 20th century (the only block built as an office).

Notable residents include John Hughes Bennett (1).

Wemyss Place

Named after the Earl of Moray's step-mother, Lady Margaret Wemyss, daughter of David Wemyss, 4th Earl of Wemyss. Wemyss Place is peripheral to the estate and visually links more to Queen Street and Heriot Row. It is one of the few sections built with a mews (accessed through a central pend). The central block was built as St Stephen's Free Church and in WW2 its open interior allowed use as a drill hall for Edinburgh's Home Guard and rather ridiculously (under the wartime rules) had to be painted in camouflage colours (making it very obvious). Repainted grey after the war it was only restored to natural stone in the late 20th century. Due to the high damage done by the paint to the stone a high proportion of the rear is wholly modern. The grey paint still survives on the arched vault of the pend leading from front to back.

Notable residents include George Smith (Scottish architect) (8), William Guy (dentist) and John Smith (dentist) (11)

References

- Youngson, A. J. (2019). The making of classical Edinburgh 1750-1840 (2019 ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1474448017.

- Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh by Gifford, McWilliam and Walker

- "History – MORAY FEU". morayfeu.com. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- 1852 OS map

- The Making of Classical Edinburgh by A J Youngson

- Edinburgh Post Office Directories 1835 to 1910

- Edinburgh: location of air raid shelters 1940

- "General register house" (PDF). nrscotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Charlotte Square, West Register House (Former St George's Church) (Lb27360)".

- "Works begin (At last) on CCWEL". 8 February 2022.

- "Have your say on Randolph Place proposals - the NEN - North Edinburgh News". 17 February 2018.

- Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1910

- The Moray Feu, Edinburgh ISBN 978-1-739045-2-5