Montreal melon

The Montreal melon, also known as the Montreal market muskmelon or the Montreal nutmeg melon (French: melon de Montréal), is a variety of melon recently rediscovered and cultivated in the Montreal, Quebec, Canada, area. Scientifically, it is a cultivar of Cucumis melo subspecies melo.

| 'Montreal Market' | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Genus | Cucumis |

| Species | Cucumis melo |

| Cultivar | 'Montreal Market' |

| Origin | Introduced by Washington Atlee Burpee, 1881[1] |

History

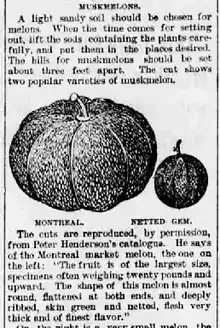

It was originally widely grown between the St. Lawrence River and Mount Royal, on the Montreal Plain. In its prime from the late 19th century until World War II, it was one of the most popular varieties of melon on the east coast of North America. The fruit was large (larger than any other melon cultivated on the continent at the time), round, netted (like a muskmelon), flattened at the ends, deeply ribbed, with a thin rind. Its flesh was light green, almost melting in the mouth when eaten. Its spicy flavor was reminiscent of nutmeg.

American newspaper reports show that the melon was also grown in Vermont in the early 20th century, and was found to be "exceedingly profitable" for the farmers.[2] One article lists the melons selling for about $10/dozen at wholesale, and from $1.25 to $1.75 each at retail in 1907.[3]

Reports from the late 19th Century tell of specimens weighing upwards of 20 lbs each: "The fruit is of the largest size, specimens often weighing twenty pounds and upward. The shape of this melon is almost round, flattened at both ends, and deeply ribbed, skin green and netted, flesh very thick and of finest flavor."[4]

The melon disappeared as Montreal grew. Its delicate rind, suitable for the family farm, was ill-suited to agribusiness. But after a couple of generations, it was rediscovered in a seed bank maintained by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Ames, Iowa, in 1996,[5] and is currently enjoying a renaissance amongst Montreal-area gardeners.

Method of cultivation

From a report dated 1909: "The seed is sown in the greenhouse or hotbed from late February to early April; later they are potted up into 3 or 4 inch pots, and when in danger of suffering for lack of root space and plant food and the weather is favorable they are removed to sash-covered frames, there to remain until they are almost fully grown. These hotbeds are well constructed, well exposed to the sun, and also protected from cold winds. The frames are often covered with two sets of sash, mats, and board shutters. With such protection, if horse manure is used to generate a sufficient bottom heat and the exposed portions of the frame are banked therewith, the plants may be grown almost as well as in a greenhouse. These frames are movable sections approximately 12 by 6, strong and tight with tie rails for the sash to slide upon.

The soil over which these sections are set is ridged up in beds 12 to 16 feet wide with a 1-foot center elevation. A trench is dug 2 feet wide, 15 to 18 inches deep, and filled almost level with well fermenting manure, and a portion of the surface soil thrown over it, slightly more being drawn in where the plants are to be set. The frames are then set in place and covered with sash, which in turn are further reinforced with mats and wooden shutters, or hay or straw with or without the shutters. A 4 to 6 foot space is allowed between the ends of each section. When the soil over the manure is well warmed up, the warmest portion of some favorable day is selected for planting. Great care is exercised now in transferring the plants from the hotbeds to guard against setbacks from sudden changes of temperature or soil conditions. The coddling process does not cease now. It is simply spread over a greater area and the plants require even closer care than before, for greater attention must be paid to watering, syringing, and ventilation, success at this stage being very largely dependent thereon.

As the fruit attains size, it is usually lifted from the soil by a shingle or flat stone, to avoid loss from cracking, rot, etc. Uniform shape, color, netting, and ripening is secured by turning the fruit every few days. When the runners fairly occupy the inclosed area the frames are raised a few inches. As the season advances more and more air is admitted until, finally, when the melons are almost full grown, the sash and then the frames themselves are entirely removed.

As each fruit sets its shoot is pinched off one or two joints beyond it. A 15 to 20 melon crop is considered sufficient from each 6 by 12 frame. Three or four hills are planted and usually two plants are set per hill.

The melons vary greatly in size. One weighing 44 pounds has been grown. The writer saw one weighing 22 pounds, which had been selected for seed purposes. Their average weight ranges from 8 to 15 pounds, and a dozen averages from 120 to 130 pounds. In exceptional cases some have been shipped weighing 240 pounds per dozen package. The larger melons are apt to be poorer in quality than those weighing 8 to 15 pounds."[6]

References

Uses public domain text from the USDA as shown (public domain due to age)

- U.P. Hedrick; F. H. Hall; L. R. Hawthorn & Alwin Berger (1937). "Part IV: The Cucurbits". The vegetables of New York. Vol. 1. New York State Agricultural Experiment Station/The Biodiversity Heritage Library. p. 81.

- Burlington weekly free press. (Burlington, Vt.), 10 Aug. 1911. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1911-08-10/ed-1/seq-16/>

- Burlington weekly free press. (Burlington, Vt.), 08 Aug. 1907. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- The Ottawa free trader. (Ottawa, Ill.), 13 June 1885. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- "Missing melon". Canadian Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- "The Montreal Musk Melon Industry". Experiment Station Work, XLIX, Farmers Bulletin 342. US Dept. of Agriculture (January 11, 1909). November 1908. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Cultural studies on the Montreal market muskmelon, Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, #169 (1912).