Montparnasse derailment

The Montparnasse derailment occurred at 16:00 on 22 October 1895 when the Granville–Paris Express overran the buffer stop at its Gare Montparnasse terminus. With the train several minutes late and the driver trying to make up for lost time, it approached the station too fast and the driver's application of the train air brake was ineffective. After running through the buffer stop, the train crossed the station concourse and crashed through the station wall; the locomotive fell onto the Place de Rennes below, where it stood on its nose. Although the passengers survived, a woman in the street below was killed by falling masonry.

| Montparnasse derailment | |

|---|---|

The wreckage of the station, photographed by Studio Lévy | |

| Details | |

| Date | 22 October 1895 16:00 |

| Location | Paris Montparnasse |

| Country | France |

| Operator | Chemins de fer de l'Ouest |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | 131 |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Injured | 6 |

Derailment

On 22 October 1895, the Granville to Paris and Montparnasse express, operated by Chemins de fer de l'Ouest, was made up of steam locomotive No. 721 (a type 2-4-0, French notation 120) hauling three luggage vans, a post van, and six passenger coaches.[1] The train had left Granville on time at 08:45, but was several minutes late as it approached its Paris Montparnasse terminus with 131 passengers on board. In an effort to make up lost time,[1][2] the train approached the station faster than usual, at a speed of 40–60 km/h (25–37 mph), and when the driver attempted to apply the Westinghouse air brake, it was faulty or ineffective.[1][3][4] The locomotive brakes alone were insufficient to stop the train, the momentum carried it into the buffers, and the locomotive crossed the almost 30-metre (98 ft) wide station concourse, crashing through a 60-centimetre (24 in) thick wall, before falling onto the Place de Rennes 10 metres (33 ft) below, where it stood on its nose.

A woman in the street below, Marie-Augustine Aguilard, was killed by falling masonry. She had been standing in for her husband, a newspaper vendor, while he went to collect the evening newspapers.[5] Two passengers, a fireman, two guards, and a passerby in the street sustained injuries.[2]

Aftermath

The locomotive driver was sentenced to two months in prison and fined 50 francs for approaching the station too fast. One of the guards was fined 25 francs as he had been preoccupied with paperwork and failed to apply the handbrake.[2]

The railway company settled with the family of the deceased woman, and arranged for the education of her two young children, as well as proposing future employment for them.

The passenger carriages were undamaged and were easily removed. It took 48 hours before the legal process and investigation allowed the railway to start removing the locomotive and tender. An attempt was made to move the locomotive with 14 horses, but this failed. A 250 tonne winch, with 10 men, first lowered the locomotive to the ground and then lifted the tender back into the station. When the locomotive reached the railway workshops it was found to have suffered little damage.[6]

Legacy

The wreckage remained outside the station for several days[3] and a number of photographs were taken, such as those attributed to Studio Lévy and Sons,[7] L. Mercier,[3] and Henri Roger-Viollet.[8]

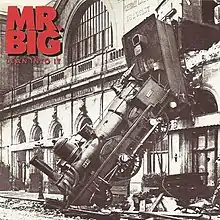

The Lévy and Sons photograph has become one of the most famous in transportation history.[9] The photograph, which is now in the public domain, is used as the cover page in the book An Introduction to Error Analysis by John Taylor.[10] The photograph is featured on the album covers for Lean Into It by American rock band Mr. Big[11] and Scrabbling at the Lock by Dutch rock band The Ex with Tom Cora, both first released in 1991,[12] and the 2019 album Warranty Void If Removed by French recording artist Dial-up Jeremy.[13]

A train crash with a similar chain of events occurs in the 1998 (season 5) episode of Thomas and Friends called "A Better View for Gordon". The incident also features during a dream in the 2007 novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret and its 2011 film adaptation, Hugo. It is depicted in the comic book series The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec,[14] in the 1978 fourth album Momies en folie.[15]

Citations

- Richou 1895, pp. 369–370.

- "Paris 1895". Danger-ahead.railfan.net. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Accident at the Gare de l'Ouest". Musee-orsay.fr. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Let's pause for a station break on Failure Magazine

- Jason Zasky: Let's Pause For a Station Break: The story behind the world's most famous train wreck photo, Failuremag.com Dated 4 Jan 2003, accessed 22 October 2018

- Richou 1895, p. 370.

- "Memorial". People.csail.mit.edu. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- "L'accident a la Gare Montparnasse". Iconicphotos.wordpress.com. 19 July 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Zasky, Jason. "Let's Pause For a Station Break: The story behind the world's most famous train wreck photo". Failuremag.com. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- John Robert Taylor (1997). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Mr. Big: Lean Into It, AllMusic, accessed 23 October 2018

- Scrabbling at the Lock, AllMusic, accessed 22 October 2018

- Warranty Void If Removed Discogs.com, accessed 9 February 2022.

- "Train". Tardi – Les Aventures Extraordinaires d'Adèle Blanc-Sec. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- "Jacques Tardi". Lambiek.net. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

General sources

- Richou, G. (9 November 1895). "L'Accident de la Gare Montparnasse". La Nature (in French). No. 1171. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

External links

Media related to the Montparnasse derailment at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to the Montparnasse derailment at Wikimedia Commons