Misinformation effect

The misinformation effect occurs when a person's recall of episodic memories becomes less accurate because of post-event information.[1] The misinformation effect has been studied since the mid-1970s. Elizabeth Loftus is one of the most influential researchers in the field. One theory is that original information and the misleading information that was presented after the fact become blended together.[2] Another theory is that the misleading information overwrites the original information.[3] Scientists suggest that because the misleading information is the most recent, it is more easily retrieved.[4]

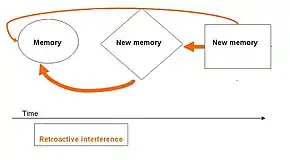

The misinformation effect is an example of retroactive interference which occurs when information presented later interferes with the ability to retain previously encoded information. Individuals have also been shown to be susceptible to incorporating misleading information into their memory when it is presented within a question.[5] Essentially, the new information that a person receives works backward in time to distort memory of the original event.[6] One mechanism through which the misinformation effect occurs is source misattribution, in which the false information given after the event becomes incorporated into people's memory of the actual event.[7] The misinformation effect also appears to stem from memory impairment, meaning that post-event misinformation makes it harder for people to remember the event.[7] The misinformation reflects two of the cardinal sins of memory: suggestibility, the influence of others' expectations on our memory; and misattribution, information attributed to an incorrect source.

Research on the misinformation effect has uncovered concerns about the permanence and reliability of memory.[8] Understanding the misinformation effect is also important given its implications for the accuracy of eyewitness testimony, as there are many chances for misinformation to be incorporated into witnesses' memories through conversations with other witnesses, police questioning, and court appearances.[9][7]

Methods

Loftus and colleagues conducts early misinformation effect studies in 1974 and 1978.[10][11] Both studies involved automobile accidents. In the latter study, participants were shown a series of slides, one of which featured a car stopping in front of a stop sign. After viewing the slides, participants read a description of what they saw. Some of the participants were given descriptions that contained misinformation, which stated that the car stopped at a yield sign. Following the slides and the reading of the description, participants were tested on what they saw. The results revealed that participants who were exposed to such misinformation were more likely to report seeing a yield sign than participants who were not misinformed.[12]

Similar methods continue to be used in misinformation effect studies. Standard methods involve showing subjects an event, usually in the form of a slideshow or video. The event is followed by a time delay and introduction of post-event information. Finally, participants are retested on their memory of the original event.[13] The original study paved the way for multiple replications of the effect in order to test things such as the specific processes initially causing the effect to occur and how individual differences influence susceptibility to the effect.

Neurological causes

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) from 2010 pointed to certain brain areas which were especially active when false memories were retrieved. Participants studied photos during an fMRI. Later, they viewed sentences describing the photographs, some of which contained information conflicting with the photographs. One day later, participants returned for a surprise item memory recognition test on the content of the photographs. Results showed that some participants created false memories, reporting the verbal misinformation conflicting with the photographs.[14] During the original event phase, increased activity in left the fusiform gyrus and the right temporal/occipital cortex was found which may have reflected the attention to visual detail, associated with later accurate memory for the critical item(s) and thus resulted in resistance to the effects of later misinformation.[14] Retrieval of true memories was associated with greater reactivation of sensory-specific cortices, for example, the occipital cortex for vision.[14] Electroencephalography research on this issue also suggests that the retrieval of false memories is associated with reduced attention and recollection related processing relative to true memories.[15]

Susceptibility

It is important to note that not everyone is equally susceptible to the misinformation effect. Individual traits and qualities can either increase or decrease one's susceptibility to recalling misinformation.[12] Such traits and qualities include age, working memory capacity, personality traits and imagery abilities.

Age

Several studies have focused on the influence of the misinformation effect on various age groups.[16] Young children — especially pre-school-aged children — are more susceptible than older children and adults to the misinformation effect.[17][18][16] Young children are particularly susceptible to this effect as it relates to peripheral memories and information, as some evidence suggests that the misinformation effect is stronger on an ancillary, existent memory than on a new, purely fabricated memory. This effect is redoubled if its source is in the form of a narrative rather than a question.[19] However, children are also more likely to accept misinformation when it is presented in specific questions rather than in open-ended questions.[17]

Additionally, there are different perspectives regarding the vulnerability of elderly adults to the misinformation effect. Some evidence suggests that elderly adults are more susceptible to the misinformation effect than younger adults.[16][20][18] Contrary to this perspective, however, other studies hold that older adults may make fewer mistakes when it comes to the misinformation effect than younger ones, depending on the type of question being asked and the skillsets required in the recall.[21] This contrasting perspective holds that the defining factor when it comes to age, at least in adults, depends largely on cognitive capacity, and the cognitive deterioration that commonly accompanies age to be the typical cause of the typically observed decline.[21] Additionally, there is some research to suggest that older adults and younger adults are equally susceptible to misinformation effects.[22]

Working memory capacity

Individuals with greater working memory capacity are better able to establish a more coherent image of an original event. Participants performed a dual task: simultaneously remembering a word list and judging the accuracy of arithmetic statements. Participants who were more accurate on the dual task were less susceptible to the misinformation effect, which allowed them to reject the misinformation.[12][23]

Personality traits

The Myers Briggs Type Indicator is one type of test used to assess participant personalities. Individuals were presented with the same misinformation procedure as that used in the original Loftus et al. study in 1978 (see above). The results were evaluated in regards to their personality type. Introvert-intuitive participants were more likely to accept both accurate and inaccurate post-event information than extrovert-sensate participants. Researchers suggested that this likely occurred because introverts are more likely to have lower confidence in their memory and are more likely to accept misinformation.[12][24] Individual personality characteristics, including empathy, absorption and self-monitoring, have also been linked to greater susceptibility.[16] Furthermore, research indicates that people are more susceptible to misinformation when they are more cooperative, dependent on rewards, and self-directed and have lower levels of fear of negative evaluation.[18]

Imagery abilities

The misinformation effect has been examined in individuals with varying imagery abilities. Participants viewed a filmed event followed by descriptive statements of the events in a traditional three-stage misinformation paradigm. Participants with higher imagery abilities were more susceptible to the misinformation effect than those with lower abilities. The psychologists argued that participants with higher imagery abilities were more likely to form vivid images of the misleading information at encoding or at retrieval, therefore increasing susceptibility.[12][25]

Paired participants

Some evidence suggests that participants, if paired together for discussion, tend to have a homogenizing effect on the memory of one another. In the laboratory, paired participants that discussed a topic containing misinformation tended to display some degree of memory blend, suggesting that the misinformation had diffused among them.[26]

Influential factors

Time

Individuals may not be actively rehearsing the details of a given event after encoding, as psychologists have found that the likelihood of incorporating misinformation increases as the delay between the original event and post-event information increases.[13] Furthermore, studying the original event for longer periods of time leads to lower susceptibility to the misinformation effect, due to increased rehearsal time.[13] Elizabeth Loftus' discrepancy detection principle argue that people's recollections are more likely to change if they do not immediately detect discrepancies between misinformation and the original event.[16][27] At times people recognize a discrepancy between their memory and what they are being told.[28] People might recollect, "I thought I saw a stop sign, but the new information mentions a yield sign, I guess I must be wrong, it was a yield sign."[28] Although the individual recognizes the information as conflicting with their own memories, they still adopt it as true.[16] If these discrepancies are not immediately detected they are more likely to be incorporated into memory.[16]

Source reliability

The more reliable the source of the post-event information, the more likely it is that participants will adopt the information into their memory.[13] For example, Dodd and Bradshaw (1980) used slides of a car accident for their original event. They then had misinformation delivered to half of the participants by an unreliable source: a lawyer representing the driver. The remaining participants were presented with misinformation, but given no indication of the source. The misinformation was rejected by those who received information from the unreliable source and adopted by the other group of subjects.[13]

Discussion and rehearsal

Psychologists have also evaluated whether discussion impacts the misinformation effect. One study examined the effects of discussion in groups on recognition. The experimenters used three different conditions: discussion in groups with a confederate providing misinformation, discussion in groups with no confederate, and a no-discussion condition. They found that participants in the confederate condition adopted the misinformation provided by the confederate. However, there was no difference between the no-confederate and no-discussion conditions, providing evidence that discussion (without misinformation) is neither harmful nor beneficial to memory accuracy.[29] Additionally, research has found that collaborative pairs showed a smaller misinformation effect than individuals, as collaborative recall allowed witnesses to dismiss misinformation generated by an inaccurate narrative.[30] Furthermore, there is some evidence suggesting that witnesses who talk with each other after watching two different videos of a burglary will claim to remember details shown in the video seen by the other witness.[31]

State of mind

Various inhibited states of mind such as drunkenness and hypnosis can increase misinformation effects.[16] Assefi and Garry (2002) found that participants who believed they had consumed alcohol showed results of the misinformation effect on recall tasks.[32] The same was true of participants under the influence of hypnosis.[33]

Arousal and stress after learning

Arousal induced after learning reduces source confusion, allowing participants to better retrieve accurate details and reject misinformation. In a study of how to reduce the misinformation effect, participants viewed four short film clips, each followed by a retention test, which for some participants included misinformation. Afterward, participants viewed another film clip that was either arousing or neutral. One week later, the arousal group recognized significantly more details and endorsed significantly fewer misinformation items than the neutral group.[34] Similarly, research also suggests that inducing social stress after presenting misinformation makes individuals less likely to accept misinformation.[35]

Anticipation

Educating participants about the misinformation effect can enable them to resist its influence. However, if warnings are given after the presentation of misinformation, they do not aid participants in discriminating between original and post-event information.[16]

Psychotropic placebos

Research published in 2008 showed that placebos enhanced memory performance. Participants were given a placebo "cognitive enhancing drug" called R273. When they participated in a misinformation effect experiment, people who took R273 were more resistant to the effects of misleading post-event information.[36] As a result of taking R273, people used stricter source monitoring and attributed their behavior to the placebo and not to themselves.[36]

Sleep

Controversial perspectives exist regarding the effects of sleep on the misinformation effect. One school of thought supports the idea that sleep can increase individuals' vulnerability to the misinformation effect. In a study examining this, some evidence was found that misinformation susceptibility increases after a sleeping cycle. In this study, the participants that displayed the least degree of misinformation susceptibility were the ones who had not slept since exposure to the original information, indicating that a cycle of sleep increased susceptibility.[21] Researchers have also found that individuals display a stronger misinformation effect when they have a 12-hour sleep interval in between witnessing an event and learning misinformation than when they have a 12-hour wakefulness interval in between the event and the introduction of misinformation.[37]

In contrast, a different school of thought holds that sleep deprivation leads to greater vulnerability to the misinformation effect. This view holds that sleep deprivation increases individual suggestibility.[38] This theory posits that this increased susceptibility would result in a related increase in the development of false memories.[26][39]

Other

Most obviously, leading questions and narrative accounts can change episodic memories and thereby affect witness' responses to questions about the original event. Additionally, witnesses are more likely to be swayed by misinformation when they are suffering from alcohol withdrawal[30][40] or sleep deprivation,[30][41] when interviewers are firm as opposed to friendly,[30][42] and when participants experience repeated questioning about the event.[30][43]

Struggles with addressing the misinformation effect

The misinformation effect can have dire consequences on decision making that can have harmful personal and public outcomes in a variety of circumstances. For this reason, various researchers have participated in the pursuit of a means to counter its effects, and many models have been proposed. As with Source Misattribution, attempts to unroot misinformation can have lingering unaddressed effects that do not display in short term examination. Although various perspectives have been proposed, all suffer from a similar lack of meta-analytic examination.

False confirmation

One of the problems with countering the misinformation effect, linked with the complexity of human memory, is the influence of information, whether legitimate or falsified, that appears to support the false information. The presence of these confirmatory messages can serve to validate the Misinformation as presented, making it more difficult to unroot the problem. This is particularly present in situations where the person has a desire for the information to be legitimate.[44]

Directly oppositional messages

A common method of unrooting false concepts is presenting a contrasting, "factual" message. While this would intuitively be a good means of portraying the information to be inaccurate, this type of direct opposition has been linked to an increase in misinformation belief. Some researchers hypothesize that the counter message must have at least as much support, if not more, than the initial message to present a fully developed counter-model for consideration. Otherwise, the recipient may not remember what was wrong about the information and fall back on their prior belief model due to lack of support for the new model.[45]

Exposure to the original source

Some studies suggest that the misinformation effect can occur despite exposure to accurate information.[46] This effect has been demonstrated when the participants have the ability to access an original, accurate video source at whim, and has even been demonstrated when the video is cued to the precise point in time where video evidence that refutes the misinformation is present.[46] Written and photographic contradictory evidence have also been shown to be similarly ineffective. Ultimately, this demonstrates that exposure to the original source is still not guaranteed to overcome the misinformation effect.[46]

Strategies to reduce the misinformation effect

There are a few existing evidence-based models for addressing the misinformation effect. Each of these, however, have their own limitations that impact their effectiveness.

Increased self regard

Some evidence has been shown to suggest that those suffering from the misinformation effect can often tell they are reporting inaccurate information but are insufficiently confident in their own recollections to act on this impression.[47] As such, some research suggests that increased self-confidence, such as in the form of self-affirmative messages and positive feedback, can weaken the misinformation effect.[47] Unfortunately, due to the difficulty of introducing increased self-regard in the moment, these treatment methods are held to not be particularly realistic for use in a given moment.[47]

Pretesting as a means of preventing the misinformation Effect

Another direction of study in preventing the misinformation effect is the idea of using a pretest to prevent the misinformation effect. This theory posits that a test, applied prior to the introduction of misleading information, can help maintain the accuracy of the memories developed after that point.[48] This model, however, has two primary limitations: its effects only seem to hold for one item at a time, and data supports the idea that it increases the impact of the information on the subsequent point of data. Pretesting also, paradoxically, has been linked with a decrease in accurate attributions from the original sample.[48]

The use of questions

Another model with some support is that of the use of questions. This model holds that the use of questions rather than declaratory statements prevents the misinformation effect from developing, even when the same information is presented in both scenarios. In fact, the use of questions in presenting information after the fact was linked with increased correct recall, and further with an increase in perfect recall among participants. The advocates of this view hold that this occurs because the mind incorporates definitive statements into itself, whereas it does not integrate questions as easily.[49]

Post-misinformation corrections and warnings

Correcting misinformation after it has been presented has been shown to be effective at significantly reducing the misinformation effect.[50] Similarly, researchers have also examined whether warning people that they might have been exposed to misinformation after the fact impacts the misinformation effect.[51][16] A meta-analysis of studies researching the effect of warnings after the introduction of misinformation found that warning participants about misinformation was an effective way to reduce — though not eliminate — the misinformation effect.[51] However, the efficacy of post-warnings appears to be significantly lower when using a recall test.[51] Warnings also appear to be less effective when people have been exposed to misinformation more frequently.[16]

Implications

Current research on the misinformation effect presents numerous implications for our understanding of human memory overall.

Variability

Some reject the notion that misinformation always causes impairment of original memories.[16] Modified tests can be used to examine the issue of long-term memory impairment.[16] In one example of such a test,(1985) participants were shown a burglar with a hammer.[52] Standard post-event information claimed the weapon was a screwdriver and participants were likely to choose the screwdriver rather than the hammer as correct. In the modified test condition, post-event information was not limited to one item, instead participants had the option of the hammer and another tool (a wrench, for example). In this condition, participants generally chose the hammer, showing that there was no memory impairment.[52]

Rich false memories

Rich false memories are researchers' attempts to plant entire memories of events which never happened in participants' memories. Examples of such memories include fabricated stories about participants getting lost in the supermarket or shopping mall as children. Researchers often rely on suggestive interviews and the power of suggestion from family members, known as "familial informant false narrative procedure."[16] Around 30% of subjects have gone on to produce either partial or complete false memories in these studies.[16] There is a concern that real memories and experiences may be surfacing as a result of prodding and interviews. To deal with this concern, many researchers switched to implausible memory scenarios.[16] Researchers have also found that they were able to induce rich false memories of committing a crime in early adolescence using a false narrative paradigm.[53]

Daily applications: eyewitness testimony

The misinformation effect can be observed in many situations. In particular, research on the misinformation effect has frequently applied to eyewitness testimony and has been used to evaluate the trustworthiness of eyewitnesses' memory.[7][18][9] After witnessing a crime or accident there may be opportunities for witnesses to interact and share information.[7][9] Late-arriving bystanders or members of the media may ask witnesses to recall the event before law enforcement or legal representatives have the opportunity to interview them.[30] Collaborative recall may lead to a more accurate account of what happened, as opposed to individual responses that may contain more untruths after the fact.[30] However, there have also been instances where multiple eyewitnesses have all remembered information incorrectly.[18] Remembering even small details can be extremely important for eyewitnesses: A jury's perception of a defendant's guilt or innocence could depend on such a detail.[5] If a witness remembers a mustache or a weapon when there was none, the wrong person may be wrongly convicted.[6]

See also

References

- Wayne Weiten (2010). Psychology: Themes and Variations: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-495-60197-5.

- Challies, Dana (2011). "Whatever Gave You That Idea? False Memories Following Equivalence Training: A Behavioral Account of the Misinformation Effect". Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 96 (3): 343–362. doi:10.1901/jeab.2011.96-343. PMC 3213001. PMID 22084495.

- Davis, Ben. "What is an example of the misinformation effect?".

- Yuhwa, Han (2017). "The Misinformation Effect and the Type of Misinformation: Objects and the Temporal Structure of an Episode". The American Journal of Psychology. 130 (4): 467–476. doi:10.5406/amerjpsyc.130.4.0467. JSTOR 10.5406/amerjpsyc.130.4.0467.

- Ogle, Christin M.; Chae, Yoojin; Goodman, Gail S. (2010), "Eyewitness Testimony", The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, American Cancer Society, pp. 1–3, doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0338, ISBN 978-0-470-47921-6, retrieved 2021-05-10

- Robinson-Riegler, B., & Robinson-Riegler, G. (2004). Cognitive Psychology: Applying the Science of the Mind. Allyn & Bacon. p. 313.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Belli, Robert F.; Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1996), Rubin, David C. (ed.), "The pliability of autobiographical memory: Misinformation and the false memory problem", Remembering our Past: Studies in Autobiographical Memory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 157–179, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511527913.006, ISBN 978-0-521-46145-0, retrieved 2021-05-10

- Saudners, J.; MacLeod, Malcolm D. (2002). "New evidence on the suggestibility of memory: The role of retrieval-induced forgetting in misinformation effects". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 8 (2): 127–142. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.515.8790. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.8.2.127. PMID 12075691.

- Quigley-Mcbride, Adele; Smalarz, Laura; Wells, Gary; Quigley-Mcbride, Adele; Smalarz, Laura; Wells, Gary (2011). "Eyewitness Testimony". obo. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0026. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Palmer, John C. (1974). "Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 13 (5): 585–589. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(74)80011-3. S2CID 143526400.

- Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Miller, David G.; Burns, Helen J. (1978). "Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 4 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19. ISSN 0096-1515. PMID 621467.

- Lee, Kerry (2004). "Age, Neuropsychological, and Social Cognitive Measures as Predictors of Individual Differences in Susceptibility to the Misinformation Effect". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 18 (8): 997–1019. doi:10.1002/acp.1075. S2CID 58925370.

- Vornik, L.; Sharman, Stefanie; Garry, Maryanne (2003). "The power of the spoken word: Sociolinguistic cues influence the misinformation effect". Memory. 11 (1): 101–109. doi:10.1080/741938170. PMID 12653492. S2CID 25328659.

- Baym, C. (2010). "Comparison of neural activity that leads to true memories, false memories, and forgetting: An fMRI study of the misinformation effect". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 10 (3): 339–348. doi:10.3758/cabn.10.3.339. PMID 20805535.

- Kiat, John E.; Belli, Robert F. (2017). "An exploratory high-density EEG investigation of the misinformation effect: Attentional and recollective differences between true and false perceptual memories". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 141: 199–208. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2017.04.007. ISSN 1074-7427. PMID 28442391. S2CID 4421445.

- Loftus, E. (2005). "Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory". Learning & Memory. 12 (4): 361–366. doi:10.1101/lm.94705. PMID 16027179.

- Bruck, Maggie; Ceci, Stephen J. (February 1999). "The Suggestibility of Children's Memory". Annual Review of Psychology. 50 (1): 419–439. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.419. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 10074684.

- Frenda, Steven J.; Nichols, Rebecca M.; Loftus, Elizabeth F. (2011-02-01). "Current Issues and Advances in Misinformation Research". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20 (1): 20–23. doi:10.1177/0963721410396620. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 54061899.

- Gobbo, Camilla (March 2000). "Assessing the effects of misinformation on children's recall: how and when makes a difference". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 14 (2): 163–182. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(200003/04)14:2<163::aid-acp630>3.0.co;2-h. ISSN 0888-4080.

- Wylie, L. E.; Patihis, L.; McCuller, L. L.; Davis, D.; Brank, E. M.; Loftus, E. F.; Bornstein, B. H. (2014). Misinformation effects in older versus younger adults: A meta-analysis and review. ISBN 978-1-317-80300-3.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Roediger, Henry L.; Geraci, Lisa (2007). "Aging and the misinformation effect: A neuropsychological analysis" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 33 (2): 321–334. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.321. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 17352614. S2CID 10651997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-15.

- Tessoulin, Marine; Galharret, Jean-Michel; Gilet, Anne-Laure; Colombel, Fabienne (2020-01-01). "Misinformation Effect in Aging: A New Light with Equivalence Testing". The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 75 (1): 96–103. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbz057. hdl:10.1093/geronb/gbz057. ISSN 1079-5014. PMID 31075169.

- Jaschinski, U., & Wentura, D. (2004). "Misleading postevent information and working memory capacity: an individual differences approach to eyewitness memory". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 16 (2): 223–231. doi:10.1002/acp.783.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ward, R.A., & Loftus, E.F., RA; Loftus, EF (1985). "Eyewitness performance in different psychological types". Journal of General Psychology. 112 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1080/00221309.1985.9711003. PMID 4056764.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dobson, M., & Markham, R., M; Markham, R (1993). "Imagery ability and source monitoring: implications for the eyewitness memory". British Journal of Psychology. 84: 111–118. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02466.x. PMID 8467368.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Skagerberg, Elin M.; Wright, Daniel B. (May 2008). "The co-witness misinformation effect: Memory blends or memory compliance?". Memory. 16 (4): 436–442. doi:10.1080/09658210802019696. ISSN 0965-8211. PMID 18432487. S2CID 27539511.

- Tousignant, J.; Hall, David; Loftus, Elizabeth (1986). "Discrepancy detection and vulnerability to misleading postevent information". Memory & Cognition. 14 (4): 329–338. doi:10.3758/bf03202511. PMID 3762387.

- Loftus, E.; Hoffman, Hunter G. (1989). "Misinformation and memory: The creation of new memories". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 188 (1): 100–104. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.118.1.100. PMID 2522502. S2CID 14101134.

- Paterson, Helen M.; Kemp, Richard I.; Forgas, Joseph P. (2009). "Co-Witnesses, Confederates, and Conformity: Effects of Discussion and Delay on Eyewitness Memory". Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 16 (sup1): S112–S124. doi:10.1080/13218710802620380. S2CID 145682214.

- Karns, T.; Irvin, S.; Suranic, S.; Rivardo, M. (2009). "Collaborative recall reduces the effect of a misleading post event narrative". North American Journal of Psychology. 11 (1): 17–28.

- Paterson, Helen M.; Kemp, Richard I.; Ng, Jodie R. (2011). "Combating Co-witness contamination: Attempting to decrease the negative effects of discussion on eyewitness memory". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 25 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1002/acp.1640.

- Assefi, S.; Garry, Maryanne (2003). "Absolut memory distortions: Alcohol placebos influence the misinformation effect". Psychological Science. 14 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.01422. PMID 12564758. S2CID 13424525.

- Scoboria, A.; Mazzoni, Giuliana; Kirsch, Irving; Milling, Leonard (2002). "Immediate and persisting effects of misleading questions and hypnosis on memory reports". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 8 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.8.1.26. PMID 12009174.

- English, Shaun; Nielson, Kristy A. (2010). "Reduction of the misinformation effect by arousal induced after learning". Cognition. 117 (2): 237–242. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.08.014. PMID 20869046. S2CID 15833599.

- Nitschke, Jonas P.; Chu, Sonja; Pruessner, Jens C.; Bartz, Jennifer A.; Sheldon, Signy (2019-04-01). "Post-learning stress reduces the misinformation effect: effects of psychosocial stress on memory updating". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 102: 164–171. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.12.008. ISSN 0306-4530. PMID 30562688. S2CID 54457443.

- Parker, Sophie; Garry, Maryanne; Engle, Randall W.; Harper, David N.; Clifasefi, Seema L. (2008). "Psychotropic placebos reduce the misinformation effect by increasing monitoring at test". Memory. 16 (4): 410–419. doi:10.1080/09658210801956922. PMID 18432485. S2CID 17256678.

- Calvillo, Dustin P.; Parong, Jocelyn A.; Peralta, Briana; Ocampo, Derrick; Gundy, Rachael Van (2016). "Sleep Increases Susceptibility to the Misinformation Effect". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 30 (6): 1061–1067. doi:10.1002/acp.3259. ISSN 1099-0720.

- Blagrove, Mark (1996). "Effects of length of sleep deprivation on interrogative suggestibility". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1037/1076-898x.2.1.48. ISSN 1076-898X.

- Darsaud, Annabelle; Dehon, Hedwige; Lahl, Olaf; Sterpenich, Virginie; Boly, Mélanie; Dang-Vu, Thanh; Desseilles, Martin; Gais, Stephen; Matarazzo, Luca; Peters, Frédéric; Schabus, Manuel. "Does Sleep Promote False Memories?". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (1): 26–40. ISSN 0898-929X.

- Gudjonsson, Hannesdottir, etursson, Bjornsson (2002). "The effects of alcohol withdrawal on mental state, interrogative suggestibility and compliance: An experimental study". Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 13 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1080/09585180210122682. S2CID 144438008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blagrove, M (1996). "Effects of length of sleep deprivation on interrogative suggestibility". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1037/1076-898x.2.1.48.

- Baxter, J., Boon, J., Marley, C. (2006). "Interrogative pressure and responses to minimally leading questions". Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Roediger, H., Jacoby, J., McDermott, K. (1996). "Misinformation effects in recall: Creating false memories through repeated retrieval". Journal of Memory and Language. 35 (2): 300–318. doi:10.1006/jmla.1996.0017. S2CID 27038956.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Goodwin, Kerri A.; Hannah, Passion J.; Nicholl, Meg C.; Ferri, Jenna M. (March 2017). "The Confident Co-witness: The Effects of Misinformation on Memory After Collaborative Discussion". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 31 (2): 225–235. doi:10.1002/acp.3320. ISSN 0888-4080.

- Chan, Man-pui Sally; Jones, Christopher R.; Hall Jamieson, Kathleen; Albarracín, Dolores (2017-09-12). "Debunking: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychological Efficacy of Messages Countering Misinformation". Psychological Science. 28 (11): 1531–1546. doi:10.1177/0956797617714579. ISSN 0956-7976. PMC 5673564. PMID 28895452.

- Polak, Mateusz; Dukała, Karolina; Szpitalak, Malwina; Polczyk, Romuald (2015-07-24). "Toward a Non-memory Misinformation Effect: Accessing the Original Source Does Not Prevent Yielding to Misinformation". Current Psychology. 35 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1007/s12144-015-9352-8. ISSN 1046-1310. S2CID 142215554.

- Blank, Hartmut (September 1998). "Memory States and Memory Tasks: An Integrative Framework for Eyewitness Memory and Suggestibility". Memory. 6 (5): 481–529. doi:10.1080/741943086. ISSN 0965-8211. PMID 10197161.

- Huff, Mark J.; Weinsheimer, Camille C.; Bodner, Glen E. (2015-09-15). "Reducing the Misinformation Effect Through Initial Testing: Take Two Tests and Recall Me in the Morning?". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 30 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1002/acp.3167. ISSN 0888-4080. PMC 4776340. PMID 26949288.

- Lee, Yuh-shiow; Chen, Kuan-Nan (2012-04-17). "Post-event information presented in a question form eliminates the misinformation effect". British Journal of Psychology. 104 (1): 119–129. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2012.02109.x. ISSN 0007-1269. PMID 23320446.

- Crozier, William E.; Strange, Deryn (2019). "Correcting the misinformation effect". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 33 (4): 585–595. doi:10.1002/acp.3499. ISSN 1099-0720. S2CID 149896487.

- Blank, Hartmut; Launay, Céline (2014-06-01). "How to protect eyewitness memory against the misinformation effect: A meta-analysis of post-warning studies". Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 3 (2): 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.03.005. ISSN 2211-3681.

- McCloskey, M.; Zaragoza, Maria (1985). "Misleading postevent information and memory for events: Arguments and evidence against memory impairment hypotheses". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 114 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.114.1.1. PMID 3156942. S2CID 16314512.

- Shaw, Julia; Porter, Stephen (2015-03-01). "Constructing Rich False Memories of Committing Crime". Psychological Science. 26 (3): 291–301. doi:10.1177/0956797614562862. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 25589599. S2CID 4869911.