Midas

Midas (/ˈmaɪdəs/; Greek: Μίδας) was the name of a king in Phrygia with whom several myths became associated, as well as two later members of the Phrygian royal house.

The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ability to turn everything he touched into gold. This came to be called the golden touch, or the Midas touch.[1] The legends told about this Midas and his father Gordias, credited with founding the Phrygian capital city Gordium and tying the Gordian Knot, indicate that they were believed to have lived sometime in the 2nd millennium BC, well before the Trojan War. However, Homer does not mention Midas or Gordias, while instead mentioning two other Phrygian kings, Mygdon and Otreus.

The Phrygian city Midaeum was presumably named after him, and this is probably also the Midas that according to Pausanias founded Ancyra (today known as Ankara).[2]

Another King Midas ruled Phrygia in the late 8th century BC. Most historians believe this Midas is the same person as the Mita, called king of the Mushki in Assyrian texts, who warred with Assyria and its Anatolian provinces during the same period.[3] A third Midas is said by Herodotus to have been a member of the royal house of Phrygia in the 6th century BC.

Mythological Midas

There are many, and often contradictory, legends about the most ancient King Midas. In one, Midas was king of Pessinus, a city of Phrygia, who as a child was adopted by King Gordias and Cybele, the goddess whose consort he was, and who (by some accounts) was the goddess-mother of Midas himself.[4] Some accounts place the youth of Midas in Macedonian Bermion (see Bryges).[5] In Thracian Mygdonia,[6] Herodotus referred to a wild rose garden at the foot of Mount Bermion as "the garden of Midas son of Gordias, where roses grow of themselves, each bearing sixty blossoms and of surpassing fragrance".[7] Herodotus says elsewhere that Phrygians lived in ancient Europe, where they were known as Bryges,[8] and the existence of the garden implies that Herodotus believed that Midas lived prior to a Phrygian migration to Anatolia.

According to some accounts, Midas had a son, Lityerses,[9] the demonic reaper of men, but in some variations of the myth he instead had a daughter, Zoë, whose name means "life". According to other accounts he had a son named Anchurus.[10]

Arrian gives an alternative story of the descent and life of Midas. According to him, Midas was the son of Gordios, a poor peasant, and a Telmissian maiden of the prophetic race. When Midas grew up to be a handsome and valiant man, the Phrygians were harassed by civil discord, and consulting the oracle, they were told that a wagon would bring them a king, who would put an end to their discord. While they were still deliberating, Midas arrived with his father and mother, and stopped near the assembly, wagon and all. They, comparing the oracular response with this occurrence, decided that this was the person whom the god told them the wagon would bring. They therefore appointed Midas king and he, putting an end to their discord, dedicated his father’s wagon in the citadel as a thank-offering to Zeus the king. In addition to this the following saying was current concerning the wagon, that whosoever could loosen the cord of the yoke of this wagon, was destined to gain the rule of Asia. This someone was to be Alexander the Great.[11] In other versions of the legend, it was Midas' father Gordias who arrived humbly in the cart and made the Gordian Knot.

Herodotus said that a "Midas son of Gordias" made an offering to the Oracle of Delphi of a royal throne "from which he made judgments" that were "well worth seeing", and that this Midas was the only foreigner to make an offering to Delphi before Gyges of Lydia.[12] The historical Midas of the 8th century BC and Gyges of Lydia are believed to have been contemporaries, so it seems most likely that Herodotus believed that the throne was donated by the earlier, legendary King Midas. However, some historians believe that this throne was donated by the later, historical King Midas, great grandfather of Alyattes of Lydia who was also referred to as Midas after amassing huge wealth from inventing taxable coinage using electrum sourced from Midas' famed river Pactolus.[13][14]

Golden Touch

One day, as Ovid relates in Metamorphoses XI,[15] Dionysus found that his old schoolmaster and foster father, the satyr Silenus, was missing.[16] The old satyr had been drinking wine and wandered away drunk, to be found by some Phrygian peasants who carried him to their king, Midas (alternatively, Silenus passed out in Midas' rose garden). Midas recognized him and treated him hospitably, entertaining him for ten days and nights with politeness, while Silenus delighted Midas and his friends with stories and songs.[17] On the eleventh day, he took Silenus back to Dionysus in Lydia. Dionysus offered Midas his choice of whatever reward he wished for. Midas asked that whatever he might touch should be changed into gold.

Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched an oak twig and a stone; both turned to gold. Overjoyed, as soon as he got home, he touched every rose in the rose garden, and all became gold. He ordered the servants to set a feast on the table. Upon discovering how even the food and drink turned into gold in his hands, he regretted his wish and cursed it. Claudian states in his In Rufinum: "So Midas, king of Lydia, swelled at first with pride when he found he could transform everything he touched to gold; but when he beheld his food grow rigid and his drink harden into golden ice then he understood that this gift was a bane and in his loathing for gold, cursed his prayer."[18]

In a version told by Nathaniel Hawthorne in A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1852), Midas' daughter came to him, upset about the roses that had lost their fragrance and become hard, and when he reached out to comfort her, found that when he touched his daughter, she turned to gold as well. Now, Midas hated the gift he had coveted. He prayed to Dionysus, begging to be delivered from starvation. Dionysus heard his prayer, and consented; telling Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. Then, whatever he put into the water would be reversed of the touch.

Midas did so, and when he touched the waters, the power flowed into the river, and the river sands turned into gold. This explained why the river Pactolus was so rich in gold and electrum, and the wealth of the dynasty of Alyattes of Lydia claiming Midas as its forefather no doubt the impetus for this origin myth. Gold was perhaps not the only metallic source of Midas' riches: "King Midas, a Phrygian, son of Cybele, first discovered black and white lead".[19]

However, according to Aristotle, legend held that Midas eventually died of starvation as a result of his "vain prayer" for the gold touch, the curse never being lifted.[20]

Ears of a donkey

Midas, now hating wealth and splendor, moved to the country and became a worshipper of Pan, the god of the fields and satyrs.[21] Roman mythographers[22] asserted that his tutor in music was Orpheus.

.jpg.webp)

Once, Pan had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo, and challenged Apollo to a trial of skill (also see Marsyas). Tmolus, the mountain-god, was chosen as umpire. Pan blew on his pipes and, with his rustic melody, gave great satisfaction to himself and his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and all but one agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented, and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer, and said "Must have ears of an ass!", which caused Midas's ears to become those of a donkey.[23] The myth is illustrated by two paintings, "Apollo and Marsyas" by Palma il Giovane (1544–1628), one depicting the scene before, and one after, the punishment. Midas was mortified at this mishap. He attempted to hide his misfortune under an ample turban or headdress, but his barber of course knew the secret, so was told not to mention it. However, the barber could not keep the secret. He went out into a meadow, dug a hole in the ground, whispered the story into it, then covered the hole up. A thick bed of reeds later sprang up from the covered up hole, and began whispering the story, saying "King Midas has an ass's ears".[24] Some sources, such as Plutarch, say that Midas committed suicide by drinking bull's blood, a powdered crystal substance which was used in the ancient world as pigment for red paint, but very toxic due to its high level of arsenic.

Sarah Morris demonstrated (Morris, 2004) that donkeys' ears were a Bronze Age royal attribute, borne by King Tarkasnawa (Greek Tarkondemos) of Mira, on a seal inscribed in both Hittite cuneiform and Luwian hieroglyphs. In this connection, the myth would appear for Greeks to justify the exotic attribute.

The stories of the contests with Apollo of Pan and Marsyas were very often confused, so Titian's Flaying of Marsyas includes a figure of Midas (who may be a self-portrait), though his ears seem normal.[25]

Similar myths in other cultures

In pre-Islamic legend of Central Asia, the king of the Ossounes of the Yenisei basin had donkey's ears. He would hide them, and order each of his barbers murdered to hide his secret. The last barber among his people was counselled to whisper the heavy secret into a well after sundown, but he didn't cover the well afterwards. The well water rose and flooded the kingdom, creating the waters of Lake Issyk-Kul.[26]

According to an Irish legend, the king Labraid Loingsech had horse/donkeys's ears, something he was concerned to keep quiet. He had his hair cut once a year, and the barber, who was chosen by lot, was immediately put to death. A widow, hearing that her only son had been chosen to cut the king's hair, begged the king not to kill him, and he agreed, so long as the barber kept his secret. The burden of the secret was so heavy that the barber fell ill. A druid advised him to go to a crossroads and tell his secret to the first tree he came to, and he would be relieved of his burden and be well again. He told the secret to a large willow. Soon after this, however, a harper named Craiftine broke his instrument, and made a new one out of the very willow the barber had told his secret to. Whenever he played it, the harp sang "Labraid Lorc has horse's ears". Labraid repented of all the barbers he had put to death and admitted his secret.[27]

In Ireland, at Loch Ine, West Cork, there is a similar story told of the inhabitant of its island, who had ass's ears. Anyone engaged to cut this King's hair was then put to death. But the reeds (in the form of a musical flute) spoke of them and the secret was out.

The myth is also known in Brittany where the king Mark of Cornwall is believed to have ruled the south-western region of Cornouaille. Chasing a white doe, he loses his best horse Morvarc'h (Seahorse) when the doe kills it with an arrow thrown by Mark. Trying to kill the doe, he is cursed by Dahut, a magician who lives under the sea. She gives life to Morvarc'h back but switches his ears and mane with Mark's ears and hair. Worried that the word might get out, Mark hides in his castle and kills every barber that comes to cut his hair until his milk brother Yeun is the last barber alive in Cornouaille. He promises to let him live if Yeun keeps the secret and Yeun cuts his hairs with a magical pair of scissors. The secret is too heavy for Yeun though and he goes to a beach to dig a hole and tell his secret in it. When he leaves, three reeds appear. Years later, when Mark's sister marries, the musicians are unable to play for the reeds of their bagpipes and bombards have been stolen by korrigans. They find three reeds on the beach and use them to make new ones, but the music instruments, instead of playing music, only sing "The King Mark has the ears and the mane of his horse Morvarc'h on his head" and Mark departs never to be seen again.[28]

Midas (8th century BC)

Another King Midas ruled Phrygia in the late 8th century BC, up until the sacking of Gordium by the Cimmerians, when he is said to have committed suicide. Most historians believe this Midas is the same person as the Mita, called king of the Mushki in Assyrian texts, who warred with Assyria and its Anatolian provinces during the same period.[3]

The King Midas who ruled Phrygia in the late 8th century BC is known from Greek and Assyrian sources. According to the former, he married a Greek princess, Damodice, daughter of Agamemnon of Cyme, and traded extensively with the Greeks. Damodice is credited with inventing coined money by Julius Pollux after she married Midas.[29] Some historians believe this Midas donated the throne that Herodotus says was offered to the Oracle of Delphi by "Midas son of Gordias" (see above). Assyrian tablets from the reign of Sargon II record attacks by a "Mita", king of the Mushki, against Assyria's eastern Anatolian provinces. Some historians believe Assyrian texts called this Midas king of the "Mushki" because he had subjected the eastern Anatolian people of that name and incorporated them into his army. Greek sources including Strabo[30] say that Midas committed suicide by drinking bull's blood during an attack by the Cimmerians, which Eusebius dated to around 695 BC and Julius Africanus to around 676 BC. Archeology has confirmed that Gordium was destroyed and burned around that time.[31]

Possible tomb

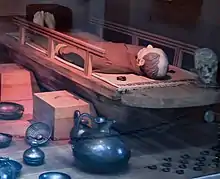

In 1957, Rodney Young and a team from the University of Pennsylvania opened a chamber tomb at the heart of the Great Tumulus (in Greek, Μεγάλη Τούμπα)—53 metres in height, about 300 metres in diameter—on the site of ancient Gordion (modern Yassıhüyük, Turkey), where there are more than 100 tumuli of different sizes and from different periods.[32] They discovered a royal burial, its timbers dated as cut to about 740 BC[33] complete with remains of the funeral feast and "the best collection of Iron Age drinking vessels ever uncovered".[34] This inner chamber was rather large: 5.15 metres by 6.2 metres in breadth and 3.25 metres high. On the remains of a wooden coffin in the northwest corner of the tomb lay a skeleton of a man 1.59 metres in height and about 60 years old.[35] In the tomb were found an ornate inlaid table, two inlaid serving stands, and eight other tables, as well as bronze and pottery vessels and bronze fibulae.[36] Although no identifying texts were originally associated with the site, it was called Tumulus MM (for "Midas Mound") by the excavator. As this funerary monument was erected before the traditional date given for the death of King Midas in the early 7th century BC, it is now generally thought to have covered the burial of his father.

Midas (6th century BC)

A third Midas is said by Herodotus to have been a member of the royal house of Phrygia and the grandfather of Adrastus, son of Gordias who fled Phrygia after accidentally killing his brother and took asylum in Lydia during the reign of Croesus. Phrygia was by that time a Lydian subject. Herodotus says that Croesus regarded the Phrygian royal house as "friends" but does not mention whether the Phrygian royal house still ruled as (vassal) kings of Phrygia.[37]

See also

- Philosopher's stone, mythical object in Alchemy, purported to transmute base materials into gold

- The Golden Touch, a Walt Disney Silly Symphony cartoon based on the Greek myth of King Midas

- The Chocolate Touch, a children's book about a boy who turns everything he touches to chocolate

Notes

- In alchemy, the transmutation of an object into gold is known as chrysopoeia.

- Pausanias 1.4.5.

- See for example Encyclopædia Britannica; also: "Virtually the only figure in Phrygian history who can be recognized as a distinct individual", begins Lynn E. Roller, "The Legend of Midas", Classical Antiquity, 22 (October 1983):299–313.

- "King Midas, a Phrygian, son of Cybele" (Hyginus, Fabulae 274).

- "Bromium" in Graves 1960:83.a; Greek traditions of the migration from Macedon to Anatolia are examined—as purely literary constructions—in Peter Carrington, "The Heroic Age of Phrygia in Ancient Literature and Art" Anatolian Studies 27 (1977:117–126).

- Mygdonia became part of Macedon in historical times.

- Herodotus, Histories 8.138.1

- Herodotus 7.73

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 10.415b, quoting Sositheus

- Plutarch, Parallela minora 5

- Arrian, Alexandri Anabasis, B.3.4–6

- Herodotus I.14.

- "coin - Origins of coins | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, notes to Penguin edition of Herodotus.

- "OVID, METAMORPHOSES 11 - Theoi Classical Texts Library". www.theoi.com.

- This myth appears in a fragment of Aristotle, Eudemus, (fr.6); Pausanias was aware that Midas mixed water with wine to capture Silenus (Description of Greece 1.4.1); a muddled version is recounted in Flavius Philostratus' Life of Apollonius of Tyana, vi.27: "Midas himself had some of the blood of satyrs in his veins, as was clear from the shape of his ears; and a satyr once, trespassing on his kinship with Midas, made merry at the expense of his ears, not only singing about them, but piping about them. Well, Midas, I understand, had heard from his mother that when a satyr is overcome by wine he falls asleep, and at such times comes to his senses and will make friends with you; so he mixed wine which he had in his palace in a fountain and let the satyr get at it, and the latter drank it up and was overcome".

- Aelian, Varia Historia iii.18 relates some of Silenus' accounts (Graves 1960:83.b.3).

- Claudian, In Rufinum: "sic rex ad prima tumebat Maeonius, pulchro cum verteret omnia tactu; sed postquam riguisse dapes fulvamque revinctos in glaciem vidit latices, tum munus acerbum sensit et inviso votum damnavit in auro."

- Hyginus, Fabulae 274

- Aristotle, Politics 1.1257b

- This myth puts Midas in another setting. "Midas himself had some of the blood of satyrs in his veins, as was clear from the shape of his ears" was the assertion of Flavius Philostratus, in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana (vi.27), not always a dependable repository of myth. (on-line Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- Cicero On Divinationi.36; Valerius Maximus, i.6.3; Ovid, Metamorphoses, xi.92f.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 191.

- The whispering sound of reeds is an ancient literary trope: the Sumerian Instructions of Shuruppak (3rd millennium BCE) warn "The reed-beds are ..., they can hide (?) slander". (Instructions of Shuruppak, lines 92–93).

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, pp. 27–28, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- The legend is related in Ella Maillart, Dervla Murphy, Turkestan solo: a journey through Central Asia (1938) 2005:48f; a wholly separate origin uncontaminated by the legend of Midas is not likely.

- Geoffrey Keating, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn 1.29–1.30

- Larvol, Gwenole. Ar Roue Marc'h a zo gantañ war e benn moue ha divskouarn e varc'h Morvarc'h. Saint-Breuc, TES. 2010.

- The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology, Martin Persson Nilsson, University of California Press, 1972, p. 48

- Strabo I.3.21.

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Rodney Young, Three Great Early Tumuli: The Gordion Excavations Final Reports, Volume 1, (1981):79–102.

- DeVries, Keith (2005). "Greek Pottery and Gordion Chronology". In Kealhofer, Lisa (ed.). The Archaeology of Midas and the Phrygians: Recent Work at Gordion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. pp. 42ff. ISBN 1-931707-76-6. Manning, Sturt; et al. (2001). "Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze-Iron Ages". Science. 294 (5551): 2532–2535 [p. 2534]. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2532M. doi:10.1126/science.1066112. PMID 11743159. S2CID 33497945.

- "King Midas' modern mourners". Science News. November 4, 2000.

- Simpson, Elizabeth (1990). "Midas' Bed and a Royal Phrygian Funeral". Journal of Field Archaeology. 17 (1): 69–87. doi:10.1179/009346990791548484.

- Young (1981):102–190. Simpson, Elizabeth (1996). "Phrygian Furniture from Gordion". In Herrmann, Georgina (ed.). The Furniture of Western Asia: Ancient and Traditional. Mainz: Philipp Von Zabern. pp. 187–209. ISBN 3-8053-1838-3.

- Herodotus I.35.

References

- Graves, Robert, 1960. The Greek Myths, rev. ed., 83.a-g.

- Sarah Morris, "Midas as Mule: Anatolia in Greek Myth and Phrygian Kingship" (abstract), American Philological Society Annual Meeting, 2004.

- "The Funerary feast of King Midas" (University of Pennsylvania) Archived 2007-02-04 at the Wayback Machine – "Tomb of Midas" report

- Calos Parada, "Midas" – Separating historical Midas from mythical Midas.

- Herodotus on Midas

- Theoi.com Classical references to Midas, in English translations.

- "Reconstruction of King Midas" – Reconstruction of "King Midas" by Richard Neave

Further reading

- Vassileva, Maya. "King Midas: between the Balkans and Asia Minor". In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne, vol. 23, n°2, 1997. pp. 9–20. doi:10.3406/dha.1997.2349. [www.persee.fr/doc/dha_0755-7256_1997_num_23_2_2349]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)