Michael Woodruff

Sir Michael Francis Addison Woodruff, FRS, FRSE, FRCS (3 April 1911 – 10 March 2001) was an English surgeon and scientist principally remembered for his research into organ transplantation. Though born in London, Woodruff spent his youth in Australia, where he earned degrees in electrical engineering and medicine. Having completed his studies shortly after the outbreak of World War II, he joined the Australian Army Medical Corps, but was soon captured by Japanese forces and imprisoned in the Changi Prison Camp. While there, he devised an ingenious method of extracting nutrients from agricultural wastes to prevent malnutrition among his fellow POWs.

Sir Michael Woodruff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 April 1911 Mill Hill, London, England |

| Died | 10 March 2001 (aged 89) |

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organ transplantation |

| Institutions | Universities of Sheffield, Aberdeen, Otago, Edinburgh |

At the conclusion of the war, Woodruff returned to England and began a long career as an academic surgeon, mixing clinical work and research. Woodruff principally studied transplant rejection and immunosuppression. His work in these areas of transplantation biology led Woodruff to perform the first kidney transplant in the United Kingdom, on 30 October 1960. For this and his other scientific contributions, Woodruff was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1968 and made a Knight Bachelor in 1969. Although retiring from surgical work in 1976, he remained an active figure in the scientific community, researching cancer and serving on the boards of various medical and scientific organisations.

Early life

Michael Woodruff was born on 3 April 1911 in Mill Hill,[2] London, England, the son of Harold Addison Woodruff and his wife, Margaret Ada Cooper.[3] In 1913, his father, Harold Woodruff, a professor of veterinary medicine at the Royal Veterinary College in London, moved the family to Australia so he could take up the post of Professor of Veterinary Pathology and Director of the Veterinary Institute at the University of Melbourne. The elder Woodruff later became the Professor of Bacteriology.[3] The family's new life in Australia was interrupted by World War I, which prompted Harold to enlist in the armed services. He became an officer in the Australian Army Veterinary Corps and was sent to Egypt.[4]

The remainder of the Woodruffs returned to London, and the two boys lived with their mother and paternal grandmother in the latter's residence in Finchley. Michael and his brother went back to Australia in 1917 after their mother, Margaret, died of a staphylococcal septicaemia. The two then spent a short time under the care of an aunt before being rejoined by their father in 1917.[3][5]

In 1919, Harold remarried and his new wife raised the children from his first marriage. The two boys did their early schooling at Trinity Grammar School in Melbourne. From then on he spent all of his youth in Australia except for a year in Europe in 1924 when his father went on sabbatical leave at Paris's Pasteur Institute. During this time, Woodruff and his brother boarded at Queen's College in Taunton, Somerset on the south coast of England. The headmaster at the school regarded Australians as "colonials" who were "backward" and put Woodruff in a year level one year lower than appropriate.[6] Upon returning to Australia, Woodruff attended the private Methodist Wesley College, where he enjoyed mathematics and rowing.[6]

He won a government scholarship to the University of Melbourne and Queen's College, a university residential college.[6] Woodruff studied electrical engineering and mathematics, receiving some instruction from the influential physicist Harrie Massey, then a tutor.[3] Despite success in engineering, Woodruff decided that he would have weak prospects as an engineer in Australia because of the Great Depression.[1] He decided to take up medical studies at the end of his third year of undergraduate study, but his parents wanted him to finish his degree first. Despite his fears regarding his ability to succeed as an engineer, Woodruff placed first in his graduating class with first-class honours. He also completed two years of the maths program with first-class honours.[6]

After graduating in 1933, he entered the medical program at the University of Melbourne. His mentors included Anatomy Professor Frederic Wood Jones. While at the University, he passed the primary exam for the Royal College of Surgeons in 1934, one of only four successful candidates who sat the examination in Melbourne that year. He finished the program in 1937 and received an MBBS with honours as well as two prizes in surgery. After graduation, he studied internal medicine for one more year, and served as a house surgeon at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.[3] Woodruff then started his surgical training.[6]

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II, Woodruff joined the Australian Army Medical Corps. He stayed in Melbourne until he finished his Master of Surgery Degree in 1941. At that time, he was assigned to the Tenth Australian Army General Hospital in British Malaya as a captain in the Medical Corps. According to Woodruff, his time in Malaya was quiet and relatively leisurely as the war in the Pacific was yet to begin in earnest. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed the situation and he was posted to a casualty clearing station where he worked as an anaesthetist, before being transferred into the Singapore General Hospital. A Japanese offensive resulted in the fall of Singapore and Woodruff was taken prisoner along with thousands of other Australian and British personnel.[1][7]

After being captured, Woodruff was imprisoned in the Changi Prison Camp. In the camp, Woodruff realised that his fellow prisoners were at great risk from vitamin deficiencies due to the poor quality of the rations they were issued by the Japanese. To help fight this threat, Woodruff asked for permission from the Japanese to allow him to take responsibility for the matter, which was granted.[7] He devised a method for extracting important nutrients from grass, soya beans, rice polishings, and agricultural wastes using old machinery that he found at the camp. Woodruff later published an account of his methods through the Medical Research Council titled "Deficiency Diseases in Japanese Prison Camps".[5] Woodruff remained a POW for three and a half years and later during this period he was sent to outlying POW camps to treat his comrades. As the prisoners were not allowed to be transferred, he had to improvise in his practice.[7] During this time he also read Maingot's surgery textbook, as a copy was in the camp, and he later said that reading about the fact that skin allografts were rejected a fortnight after being initially accepted, had stoked his interest in doing research on the topic.[7]

While stationed at the River Valley Road prisoner of war hospital in Singapore in 1945, with the supplies of chemical anæsthetics severely restricted by the Japanese, Woodruff and a medical/dental colleague from the Royal Netherlands Forces successfully used hypnotism as the sole means of anæsthesia for a wide range of dental and surgical procedures.[8]

At the conclusion of World War II, Woodruff returned to Melbourne to continue his surgical training. During his studies, he served as the surgical associate to Albert Coates. This position was unpaid, so Woodruff accepted an appointment as a part-time pathology lecturer to support himself.[9] In January 1946, Woodruff participated in an Australian Student Christian Movement meeting, where he met Hazel Ashby, a science graduate from Adelaide. She made a great impression on Woodruff, and he married her half a year later. The couple were research partners for the rest of their lives.[3][9]

Early career

Soon after his marriage, Woodruff travelled to England to take the second half of the FRCS Exam. Woodruff took his new wife over with no guarantee of employment, and declined a two-year travelling fellowship to Oxford University offered by the Australian Red Cross because it required him to return home and work.[10] Before departing, he applied for a position as a Tutor of Surgery at the University of Sheffield, and learned en route that they had accepted his application. He took the FRCS exam in 1947 and passed—a result that, in Woodruff's view, was not hindered by the fact that one of his examiners, Colonel Julian Taylor, had been with him at Changi.[1]

Sheffield

After passing his exam, Woodruff entered his position at Sheffield, where he trained in emergency and elective surgery.[10] Originally, he had planned to do surgical research, but Sheffield had no space for him in its surgical lab. Instead, Woodruff was given a place in the pathology laboratory where he studied transplant rejection, a process in which the immune system of a transplant recipient attacks the transplanted tissue. Woodruff was particularly interested in thyroid allografts to the anterior chamber of the eye because they did not appear to meet with rejection.[10] Woodruff's work with the allografts gave him a solid basis to work in the developing field of transplantion and rejection. To further himself in these areas, Woodruff arranged to meet Peter Medawar, an eminent zoologist and important pioneer in the study of rejection. The two men discussed transplantation and rejection, beginning a lasting professional relationship. Despite his achievements at Sheffield, Woodruff was rejected upon applying for a post at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.[3][10]

Aberdeen

In 1948, shortly after applying for the position in Melbourne, Woodruff moved from Sheffield to the University of Aberdeen where he was given a post as a senior lecturer,[1] having not known where the Scottish city was beforehand.[10] At Aberdeen, Woodruff was given better laboratory access under Professor Bill Wilson, and was also awarded a grant that allowed his wife to be paid for her services.[11] He took advantage of this access and his wife's skills as a lab assistant to investigate in utero grafts (tissue grafts performed while the recipient was still in the womb). At the time, the surgical community hypothesized that if a recipient were given in utero grafts, he would be able to receive tissue from the donor later in life without risk of rejection. Woodruff's experiments with rats produced negative results.[12] Woodruff also commenced work on antilymphocyte serum for immunosuppression, with little initial success.[12]

While in Aberdeen, Woodruff also visited the United States on a World Health Organization (WHO) Travelling Fellowship. During the visit, he met many of the leading American surgeons, an experience that increased his own desire to continue his work and research. After returning from the US, Woodruff experimented with the effects of cortisone and the impact of blood antigen on rejection. As part of his blood antigen studies, Woodruff found two volunteers with identical blood antigens and arranged for them to exchange skin grafts. When the grafts were rejected, Woodruff determined that rejection must be controlled by additional factors.[3][12] In 1951 Woodruff was awarded a Hunterian Professorship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England for his lecture The transplantation of homologous tissue and its surgical application.[12]

Dunedin

In 1953, Woodruff moved to Dunedin in New Zealand to become Professor of Surgery at the University of Otago.[12] Woodruff had earlier failed in his applications for the corresponding position at St Mary's Hospital Medical School, London and St Andrews University in Scotland.[12] While in Dunedin, Woodruff conducted research on the use of white blood cells to increase tolerance to allografts in rats. This line of research proved unsuccessful, but some of Woodruff's other projects did well. Among his more important accomplishments in the period, Woodruff established a frozen skin bank for burn treatment. As there was no plastic surgeon in Dunedin, Woodruff ended up being responsible for treating burns. He also worked on the phenomenon known as runt disease (graft versus host disease).[3] Although Woodruff had been productive in his four years in New Zealand, Dunedin's population of 100,000 was insufficient to supply a clinical medical school, so he began to look for an appointment elsewhere.[13]

Edinburgh

In 1957, Woodruff was appointed to the Chair of Surgical Science at the University of Edinburgh without requiring an interview.[13] At the university, he split his time equally between his clinical and teaching responsibilities and his research. He was also allowed to appoint two assistant researchers who went on to become prominent in their own right, Donald Michie and James Howard. As a major part of his research, Woodruff served as the honorary director of a Research Group on Transplantation established by the Medical Research Council.[13]

The research group's principal investigations concerned immunological tolerance (the body's acceptance of tissues, as opposed to rejection), autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (especially in mice), and immune responses to cancer in various animals. In his clinical role, Woodruff started a vascular surgery program and worked with the use of immunotherapy as a cancer treatment as well as the treatment of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. However, his most important clinical accomplishments were in kidney transplantation.[3][13]

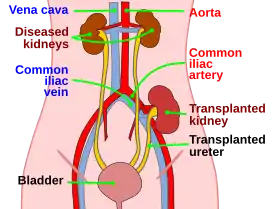

Woodruff performed the first ever kidney transplant in the UK, at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.[14] He had been waiting for the right patient for some time, hoping to find a patient with an identical twin to act as the donor, as this would significantly reduce the risk of rejection. The patient that Woodruff eventually found was a 49-year-old man suffering from severely impaired kidney function who received one of his twin brother's kidneys on 30 October 1960. The donor kidney was harvested by James Ross and transplanted by Woodruff. Both twins lived an additional six years before dying of an unrelated disease.[14] Woodruff thought that he had to be vigilant with his first kidney transplant, as he regarded the British medical community's attitude to be conservative towards transplantation.[13] From then until his retirement in 1976, he performed 127 kidney transplants.[13] Also in 1960, Woodruff published The Transplantation of Tissues and Organs, a comprehensive survey of transplant biology and one of seven books he wrote.[3] He was awarded the 1969 Lister Medal for his contributions to surgical science.[15] The corresponding Lister Oration, given at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, was delivered on 8 April 1970, and was titled 'Biological aspects of individuality'.[16]

The success of Woodruff's clinical transplant program was recognised and enhanced by funding from the Nuffield Foundation to construct and open the Nuffield Transplant Surgery Unit at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh.[17] In 1970 an outbreak of hepatitis B struck the transplant unit, resulting in the death of several patients and four of Woodruff's employees due to fulminant hepatic failure. Woodruff was deeply shaken by the loss and the unit was closed for a period while an investigation was carried out to develop a contingency plan to avoid such a disaster in future. The unit then resumed operations.[17]

Woodruff retired from the University of Edinburgh in 1976,[3] his role then being filled by Prof Geoffrey Duncan Chisholm,[18] and joined the MRC Clinical and Population Cytogenetics Unit. He spent the next ten years there, engaged in cancer research with an emphasis on tumour immunology using Corynebacterium parvum. During that time, Woodruff also published twenty-five papers and two books.[3] After retiring from his cancer research, Woodruff lived quietly with his wife in Edinburgh, travelling occasionally,[5] until his death there on 10 March 2001, a month before his 90th birthday.[1]

Legacy

Woodruff's contributions to surgery were important and long-lasting. In addition to performing the first kidney transplant in the UK, he devised a method of implanting a transplanted ureter in the bladder during transplants that is still used today. He established a large, efficient transplant unit in Edinburgh that remains one of the world's best. Although best known for these clinical accomplishments, Woodruff's contributions to the study of rejection and tolerance induction were equally important. Among these contributions, Woodruff's work with anti-lymphocyte serum has led to its wide use to reduce rejection symptoms in organ transplant recipients up to the current day.[3]

These important contributions to medicine and biology were first seriously honoured in 1968 when Woodruff was elected to be a Fellow of the Royal Society. The next year, 1969, Woodruff was knighted by the Queen, a rare accomplishment for a surgeon. Numerous medical organisations gave Woodruff honorary membership, including the American College of Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Woodruff also held office in several scientific organisations, serving as Vice-President of the Royal Society and President of The Transplantation Society. Finally, Woodruff served for many years as a WHO advisor and as a visiting professor at a number of universities.[19]

Despite his profound influence on transplantation and what Peter Morris called "a commanding presence in any gathering",[20] Woodruff was not known for his ability as a lecturer as he had a rather uncertain style of presentation and a tendency to mumble.[20] Nevertheless, Morris said that Woodruff has "a great turn of phrase and a rather wicked sense of humour".[20] Morris concluded that "What is surprising is that he was not successful in producing many surgeons in his own mould, despite the intellectual talent that was entering surgery and especially transplantation in the 1960s. However, his influence in transplantation at all levels was enormous."[20]

Publications

Woodruff's impact is also apparent in his large volume of publications. In addition to authoring over two hundred scholarly papers,[21] Woodruff wrote eight books during his career, covering numerous aspects of medicine and surgery.

- Deficiency Diseases in Japanese Prison Camps. M.R.C Special Report No. 274. H.M. Stationery Office, London 1951.

- Surgery for Dental Students. Blackwell, Oxford. (Fourth Ed., 1984 with H.E. Berry) 1954.

- The Transplantation of Tissues and Organs. Charles C. Thomas. Springfield, Illinois 1960.

- The One and the Many: Edwin Stevens Lectures for the Laity. Royal Society of Medicine, London 1970.

- On Science and Surgery. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1976.

- The Interaction of Cancer and Host: Its Therapeutic Significance. Grune Stratton, New York 1980.

- Cellular Variation and Adaptation in Cancer: Biological Basis and Therapeutic Consequences. Oxford University Press 1990.

- Nothing Venture Nothing Win. Scottish Academic Press 1996. (autobiography)

Personal life

In 1946 Woodruff married Hazel Gwenyth Ashby.[22]

The Woodruffs had two sons, followed by a daughter. Their first son completed a civil engineering degree at Sheffield University, where the daughter also attended, completing a science degree in botany. The second son did a medical degree at University College London and became an ophthalmologist.[23] Woodruff and his wife were avid tennis players and had a court in their home in Edinburgh.[20] After moving to Edinburgh, Woodruff took up sailing with the Royal Forth Yacht Club, and went on to compete in some races. He owned a boat and was known to go sailing on it in the Mediterranean each summer with his wife. During his student years, Woodruff was a keen rower and field hockey player.[20]

Woodruff was a lover of classical music, and after taking up the organ at university and learning from A. E. Floyd, the organist of St Paul's Cathedral,[6] he became the college organist at Queen’s College in Melbourne; he later learned to play the piano.[24] In his spare time, Woodruff continued to pursue his love of pure mathematics, especially number theory. He periodically attempted to prove Fermat's Last Theorem, but failed.[24]

References

- Morris, Peter (31 March 2001). "Professor Sir Michael Woodruff". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- "FreeBMD Entry Info". FreeBMD. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Morris, P. (2005). "Sir Michael Francis Addison Woodruff. 3 April 1911 – 10 March 2001: Elected F.R.S. 1968". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 51: 455–471. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2005.0030.

- Morris, p. 457.

- Woodruff, Michael. Nothing Venture Nothing Win. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7073-0737-6.

- Morris, p. 458.

- Morris, p. 459.

- Sampimon, R.L.H. & Woodruff, M.F.A., "Some Observations Concerning the use of Hypnosis as a Substitute for Anæsthesia", The Medical Journal of Australia, (23 March 1946), pp. 393–395.

- Morris, p. 460.

- Morris, p. 461.

- Morris, pp. 461–462.

- Morris, p. 462.

- Morris, p. 463.

- "History of Kidney Transplantation in Edinburgh". Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "Lister Medal". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 45 (2): 127. 1969. PMC 2387642.

- Woodruff, M. (1970). "Biological aspects of individuality". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 47 (1): 1–13. PMC 2387772. PMID 4393495.

- Morris, p. 464.

- Blandy, John P. (1 April 1997). "Geoffrey Duncan Chisholm". British Journal of Urology. 79 (S2): 1–2. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1997.tb16914.x. ISSN 1464-410X. PMID 9158539.

- Morris, p. 467.

- Morris, p. 469.

- Morris, P (2005). "Michael Francis Addison Woodruff Bibliography" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 51: 455–471. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2005.0030. S2CID 73171252.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Woodruff, Sir Michael (1996). Nothing Venture Nothing Win. Scottish Academic Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-7073-0737-6.

- Morris, p. 468.

Further reading

- Sir Michael Woodruff, The Guardian

- Leigh W (February 2011). "Sir Michael Francis Addison Woodruff (1911-2001) FRS DSc MD MS FRCS". J Med Biogr. 19 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1258/jmb.2010.010018. PMID 21350076. S2CID 207200478.

- MacDonald H (October 2015). Guarding the Public Interest: England's Coroners and Organ Transplants, 1960–1975, Journal of British Studies