Metastaseis (Xenakis)

Metastaseis (Greek: Μεταστάσεις; spelled Metastasis in correct French transliteration, or in some early writings by the composer Métastassis) is an orchestral work for 61 musicians by Iannis Xenakis. His first major work, it was written in 1953–54 after his studies with Olivier Messiaen and is about 8 minutes in length. The work was premiered at the 1955 Donaueschingen Festival with Hans Rosbaud conducting. This work was originally a part of a Xenakis trilogy titled Anastenaria (together with Procession aux eaux claires and Sacrifice) but was detached by Xenakis for separate performance.[1]

| Metastaseis | |

|---|---|

| by Iannis Xenakis | |

Iannis Xenakis in his studio in Paris, circa 1970 | |

| Native name | Μεταστάσεις |

| Style | Sound mass |

| Composed | 1953–4 |

| Duration | About 8 minutes |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 16 October 1955 |

| Location | Donaueschingen, Germany |

| Conductor | Hans Rosbaud |

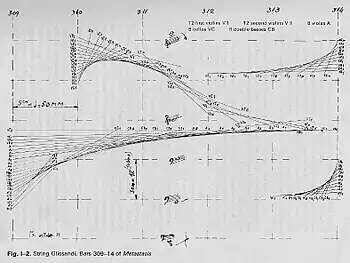

Metastaseis requires an orchestra of 61 players (12 winds, 3 percussionists playing 7 instruments, 46 strings) with no two performers playing the same part. It was written using a sound mass technique in which each player is responsible for completing glissandi at different pitch levels and times. The piece is dominated by the strings, which open the piece in unison before their split into 46 separate parts.

A ballet was choreographed to Xenakis' Metastaseis and Pithoprakta by George Balanchine (see Metastaseis and Pithoprakta). The ballet was premiered on January 18, 1968 by the New York City Ballet with Suzanne Farrell and Arthur Mitchell.

Title

The Greek title Μεταστάσεις was transliterated by the composer himself in various ways when writing in French: Les Métastassis, Métastassis, and Les Métastaseis. The Greek digraph ει is pronounced as "i" in modern Greek, and the correct French transliteration is Metastasis.[2]

The title page of the published score gives MetastaseisB in the composer's handwriting, and it appears typeset in this form on the score cover as well. The title, a portmanteau,[3] in the plural,[4] Meta (after or beyond) -stasis (immobility), refers to the dialectical contrast between movement or change and nondirectionality.[5] According to the composer's own description, "Meta=after + staseis=a state of standstills—dialectic transformations. The Metastaseis are a hinge between classical music (which includes serial music) and 'formalized music' which the composer was obliged to inculcate into composition".[6] These transformations include both the glissando mass events and the permutation of the tone rows.[7] The "B" (beta) refers to the revisions suggested by Hermann Scherchen: reduction of the strings from 12-12-12-12-4 to 12-12-8-8-6.[4]

Analysis

Metastaseis was inspired by the combination of an Einsteinian view of time and Xenakis' memory of the sounds of warfare, and structured on mathematical ideas by Le Corbusier. Music usually consists of a set of sounds ordered in time; music played backwards is hardly recognizable. Messiaen's similar observations led to his noted uses of non-retrogradable rhythms; Xenakis wished to reconcile the linear perception of music with a relativistic view of time. In warfare, as Xenakis knew it through his musical ear, no individual bullet being fired could be distinguished among the cacophony, but taken as a whole the sound of "gunfire" was clearly identifiable. The particular sequence of shots was unimportant: the individual guns could have fired in a completely different pattern from the way they actually did, but the sound produced would still have been the same. These ideas combined to form the basis of Metastaseis.

While in Newtonian physics time flows linearly at a universal rate, the Einsteinian view describes it as a function of matter and energy; change one of those quantities and time too is changed. Xenakis attempted to make this distinction in his music. While most traditional compositions depend on strictly measured time for the progress of the line, using an unvarying tempo, time signature, or phrase length, Metastaseis changes intensity, register, and density of scoring, as the musical analogues of mass and energy. It is by these changes that the piece propels itself forward: the first and third movements of the work do not have even a melodic theme or motive to hold them together, but rather depend on the strength of this conceptualization of time.

The second movement does have some sort of melodic element. A fragment of a twelve-tone row is used, with durations based on the Fibonacci sequence. (This integer sequence is nothing new to music: it was used often by Bartók, among others.) One interesting property of the Fibonacci sequence is that the further into the infinite sequence one looks, the closer the ratio of a term to its preceding term comes to the Golden Section; it doesn't take long before the result is correct to several significant figures. This idea of the Golden Section and the Fibonacci Sequence was also a favorite of Xenakis in his architectural works; the Convent de La Tourette was built on this principle. See: Modulor.

Xenakis, an accomplished architect, saw the chief difference between music and architecture as that while space is viewable from all directions, music can only be experienced from one. The preliminary sketch for Metastaseis was in graphic notation looking more like a blueprint than a musical score, showing graphs of mass motion and glissandi like structural beams of the piece, with pitch on one axis and time on the other. In fact, this design ended up being the basis for the Philips Pavilion, which had no flat surfaces but rather assumed the shape of hyperbolic paraboloids like those used to model the musical "masses" and swells of his string glissandi. Yet unlike many avant-garde composers of this century who would take such a thing as the completed score, Xenakis notated every event in traditional notation.

References

- Hoffmann, Peter, "Xenakis, Iannis", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- Barthel-Calvet, Anne-Sylvie, "MÉTASTASSIS-Analyse: Un texte inédit de Iannis Xenakis sur Metastasis", Revue de Musicologie 89, no. 1 (2003): 129–87. Citation on p. 160n72: "Le phonème « ει » se prononçant « i » en grec moderne, la transcription exacte en français est « Metastasis », orthographe couramment adoptée a l'heure actuelle". (in French)

- Bois, Mario (1967). Iannis Xenakis, the man and his music: a conversation with the composer and a description of his works, p.18. Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers.

- Harley, James (2004). Xenakis: His Life in Music, p.256n5. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97145-4. "The word metastaseis is to be understood as being in the plural form, and is in fact often misspelled through overlooking this fact.

- Harley (2004), p.10.

- Xenakis, Iannis, preface to the score, MetastaseisB (London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1967).

- Hoffman, Peter (2007–2010), "Xenakis, Iannis", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online

Further reading

- Baltensperger, André (1996). Iannis Xenakis und die Stochastische Musik. Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt. (in German) Cited in Hurley (2004), p. 356n9.

- Matossian, Nouritza: Xenakis. London: Kahn and Averill, 1990. ISBN 1-871082-17-X.

- Xenakis, Iannis: Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, second, expanded edition (Harmonologia Series No.6). Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1992. ISBN 1-57647-079-2. Reprinted, Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2001.

External links

- Los Angeles Philharmonic piece detail, Metastasis.

- Perusal score at Boosey & Hawkes (requires free registration)