Mastoid cells

The mastoid cells (also called air cells of Lenoir or mastoid cells of Lenoir) are air-filled cavities within the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the cranium. The mastoid cells are a form of skeletal pneumaticity. Infection in these cells is called mastoiditis.

| Mastoid cells | |

|---|---|

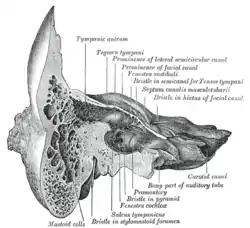

Coronal section of right temporal bone. (Mastoid cells labeled at bottom left.) | |

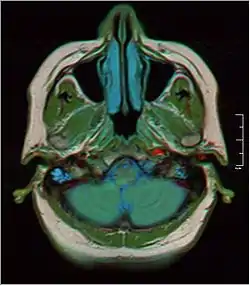

MRI showing fluid in mastoid air cells | |

| Details | |

| Artery | stylomastoid artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cellulae mastoideae |

| TA98 | A15.3.02.029 |

| TA2 | 646 |

| FMA | 72001 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The term cells here refers to enclosed spaces, not cells as living, biological units.

Anatomy

The mastoid air cells vary greatly in number, shape, and size; they may be extensive or minimal or even absent.[1]: 746

The cells are typically interconnected and their walls lined by mucosa that is continuous with that of the mastoid antrum and tympanic cavity.[1]: 746

Extent

They may excavate the mastoid process to its tip, and be separated from the posterior cranial fossa and sigmoid sinus by a mere slip of bone or not at all. They may extend into the squamous part of temporal bone, petrous part of the temporal bone zygomatic process of temporal bone, and - rarely - the jugular process of occipital bone; they may thus come to adjoin many important structures (including the bony labyrinth, tympanic cavity, external acoustic meatus, pharyngotympanic tube, superior jugular bulb, posterior cranial fossa, middle cranial fossa, carotid canal, abducens nerve, sigmoid sinus) to which they may disseminate infection in case of infective mastoiditis.[1]: 746

Innervation

The cells receive innervation from the posterior branch of the meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve (nervus spinosus),[1]: 400.e2 [2]: 364 and branches of the tympanic plexus.[1]: 749 [2]: 366

Vasculature

The cells receive arterial supply from the stylomastoid branch of the occipital artery or posterior auricular artery, and (sometimes) a mastoid branch of the occipital artery.[1]: 749

The superior petrosal sinus receives venous drainage from the mastoid air cells (mastoid infection may thus lead to a cerebellar abscess).[2]: 443

Development

At birth, the mastoid is not pneumatized, but becomes aerated before age six.[3] At birth, the mastoid antrum is well developed but the air cells are represented only by small diverticula from the antrum. The air cells then gradually extend into the bone of the mastoid during the first years of life. Their most significant enlargements takes place during puberty.[1]: 746

Function

The air cells are hypothesised to protect the temporal bone and the inner and middle ear against trauma and to regulate air pressure.[4]

Clinical significance

Infections in the middle ear easily spread into the mastoid air cells through the aditus ad antrum, resulting in mastoiditis, a potentially dangerous and life-threatening condition. Infection may then further spread into the middle cranial fossa or posterior cranial fossa, causing meningitis or abscess of adjacent brain tissue. Infection may also spread to muscles of the neck, causing pain and torticollis.[1]: 746

References

- Standring, Susan (2020). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (42th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-7020-7707-4. OCLC 1201341621.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). Elsevier Australia. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- Raphael Schillinger (July 1939) [1 July 1939]. "Pneumatization of the Mastoid: A Roentgen Study". Radiology. Radiological Society of North America. 33 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1148/33.1.54. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Ear Infections and Mastoiditis".

External links

- Anatomy image: hn1-8 at the College of Medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University