Martensdale, California

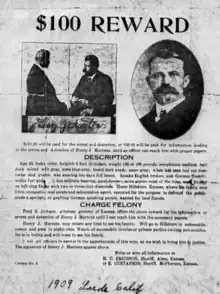

Martensdale was a town settled in Kern County, California, primarily by Mennonites from the Great Plains. The settlement was located near Lerdo, 6 mi (10 km) east of Shafter. In 1909, Henry J. Martens, claiming to own large quantities of land in California, convinced Mennonites to travel to California, where they settled, forming the town of Martensdale in June. Over the next several months, amenities such as a post office, a furniture dealer, and a grocer opened at the site, and houses were built. However, it was discovered in December that Martens did not own most of the land the town was located on, and had failed to make payments on the portion he owned. A number of lawsuits were filed against Martens in early 1910, and he was arrested in Kansas in March but not extradited. The residents of Martensdale were forced to leave the site, using wagons and log rollers to transport their homes to new sites. Many of the displaced settled in Rosedale. Martens spent the rest of his life as a fugitive and died in Kansas City in 1941.

Martensdale | |

|---|---|

Martensdale Location in California  Martensdale Martensdale (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 35°29′59″N 119°09′49″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Kern County |

| Founded | 1909 |

| Abandoned | 1910 |

History

In 1909, Henry J. Martens traveled throughout the Great Plains in the United States, claiming to own over 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of land in California. With drought conditions in the region, Martens was able to convince many Mennonites to travel to California via train. In reality, Martens only had arrangements to purchase 5,120 acres (2,070 ha) of land, which he exchanged for the abandoned farmland in the Great Plains.[1] Beginning in June 1909, Martens began showing a tract of land near Lerdo in Kern County, California, to the traveling Mennonites.[2] The first large group to visit the site decided to settle there. After hearing a message from a local minister asking them to prohibit saloons from opening in the planned city, the colonists decided to name the settlement Martensdale in honor of Martens.[2] The group also wanted to build a college for the town, and designated 100 acres (40 ha) for that purpose, as well as $16,000. Martens responded by producing 1,000 plats showing the proposed college. The small group who settled there were joined by larger numbers of settlers in the first half of October.[2]

The settlement, which was located near the present junction of the Lerdo Highway and California Highway 99,[3] gathered a number of amenities. An article in the Bakersfield Morning Echo dated November 23, 1909, reported that a large well had been dug for the community, and that it had a grocer, furniture dealer, and shoe-seller. A post office, barber shop, and hardware store were stated to be on the verge of coming to the community.[4] The colony also attracted non-Mennonites as well, as 25 German Methodists from Gotebo, Oklahoma, settled there on December 13.[5] Reports trickled back to the Great Plains that Martens had provided money for the establishment of schools for Baptists, Mennonites, Adventists, and Lutherans, although the modern writers Leland Harder and Kevin Enns-Rempel state that there is no evidence to prove that either significant Baptist and Lutheran settlement or the claimed donations actually occurred.[6] In total, over 100 families settled at Martensdale.[7] About eight percent of the town's Mennonite congregation had moved there from within other parts of California.[8]

However, Martens did not actually own the land at the site. Instead, John McWilliams Jr. had title to the land.[9] Martens was able to purchase a portion of the land on October 30, but most of the land occupied by the settlers still belonged to McWilliams.[10] However, Martens did not make the required payments on the land beyond the initial deposit paid.[11] By December, the settlers had learned that they could not live at the site; some had already built houses.[1] Martens' problems began to accumulate in 1910. In January, he was sued for failing to make payments on a land purchase and for the drilling of a well.[12] On January 29, 1910, a warrant was issued for Martens. One of the Martensdale colonists had pressed charges against him for taking $4,000 as payment for an orchard, when Martens did not have title or the right to sell it.[13] While this charge was withdrawn by the plaintiffs on January 31, three more individuals filed lawsuits against Martens in February, all for amounts in excess of $10,000. Another warrant followed on February 26, and Martens was arrested in Hillsboro, Kansas, on March 11.[12]

The houses already built at the site were moved by the settlers using wagons,[14] although several families were reported to have used log rollers for that purpose in March.[15] On April 26, the Bakersfield Morning Echo reported that an application for the closing of the post office had been made, and that it would soon close. A number of the former residents of Martensdale remained in Kern County, with many moving to Rosedale. The paper also reported that all of the residents were expected to be gone by the end of April, and that attempts by the former colonists to seek legal action against Martens were hampered by the governor of Kansas's refusal to extradite Martens to California.[16] Few traces of the town were left by the late summer.[17] Martens lived the rest of his life as a fugitive, eventually dying in Kansas City in 1941.[18] In 1949, 800 people gathered for a picnic to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Martensdale's settling.[19]

References

- Froese 2015, p. 35.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, pp. 20–21, 23.

- Enns-Rempel, Kevin (1993). "California in Their Own Words: First-Hand Accounts of Early Mennonite Life in the Golden State". California Mennonite Historical Society Bulletin (29): 6.

- "Newsletter from Martensdale". Bakersfield Morning Echo. November 23, 1909. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "Twenty-Five Colonists for Martensdale Arrive". The Bakersfield Californian. December 13, 1909. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 22.

- Durham 1998, p. 1014.

- Enns-Rempel, Kevin (1993). "They Came From Many Places: Sources of Mennonite Migration to California 1887–1939". California Mennonite Historical Society Bulletin (28): 3.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 21.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, pp. 22–23.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 24.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 25.

- "Swears Out a Warrant for Henry J. Martens". Bakersfield Morning Echo. January 29, 1910. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Froese 2015, pp. 35–36.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 28.

- "Martensdale is Only a Memory". Bakersfield Morning Echo. April 26, 1910. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 29.

- Harder & Enns-Rempel 1993, p. 34.

- "Neighborhood News". The Reedley Exponent. October 20, 1949. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

Sources

- Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, California: Word Dancer Press. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- Froese, Brian (2015). California Mennonites. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1513-0.

- Harder, Leland; Enns-Rempel, Kevin (1993). Henry J. Martens and the Mennonite Land Company: Benevolence, Entrepreneurship, or Fraud? (PDF). Fresno Pacific University.