Macronectes tinae

Macronectes tinae is an extinct species of giant petrel from the Pliocene of New Zealand. Although clearly belonging to the genus Macronectes, this species was notably smaller and less robust than either of the modern forms, possibly due to its more ancestral nature or due to the warmer climate of its environment. Like modern giant petrels it likely scavenged and hunted, feeding on the carcasses of seals and penguins as well as the chicks of other seabirds.

| Macronectes tinae Temporal range: Late Pliocene | |

|---|---|

| |

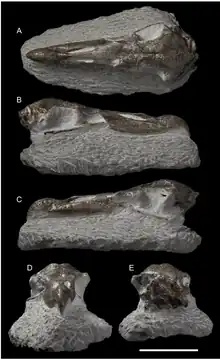

| Holotype skull of M. tinae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Macronectes |

| Species: | †M. tinae |

| Binomial name | |

| †Macronectes tinae Tennyson & Salvador, 2023 | |

History and naming

The bones of Macronectes tinae were discovered in the marine sediments of the Pliocene Tangahoe Formation, located within the Whanganui Basin of New Zealand's North Island. Both the holotype specimen, a complete skull, as well as the paratype humerus, are kept at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. The fusion of the individual elements suggest that both belonged to adult individuals, however the distance between them makes it unlikely that they belonged to a single individual, instead representing two different birds.

The skull that serves as the type specimen was the favourite fossil of Tina King, partner of fossil collector Alastair Johnson. For this reason the species was named after her.[1]

Description

The skull of M. tinae shows the characteristic bulbous beak tip known from modern species of giant petrel as well as the proportionally shortened nasal aperture.[1]

Although smaller than in other petrels, the nasal aperture of M. tinae is proportinally bigger than that of the two modern giant petrels. In fact, despite having an overall smaller skull the nasal aperture is of roughly equal total size as that of the extant species. The supraocciptal bone is shallower, only half to two thirds the depth of either modern species. However it is not certain how diagnostic this feature is, as it may also be the result of postmortem deformation. The same might account for the more prominent crista nuchalis transversa at the back of the head.[1]

The humerus appears to be the size of smaller Macronectes individuals and is proportionally less robust, with a shallower shaft. All condyles, although worn in the fossils, appear to resemble those of living petrels. The ventral epicondyle however might be better developed than in modern species and may extend further distally. This later assumption may again be the result of distortion during preservation. Regardless, the fact that the epicondyle is more pronounced is also seen in all other fulmarine petrels except for the two living Macronectes species. Another difference between M. tinae and modern giant petrels can be found in the shape of the fossa medialis brachialis. In the fossil species this fossa is elongated and almost fusiform, similar to what is seen in some specimens of Thalassoica, while modern giant petrels have a more circular fossa consistent with most other fulmarine petrels.[1]

Overall M. tinae shows similar but more gracile anatomy compared to the two modern species of giant petrel, the southern giant and northern giant petrel. This indicates that M. tinae was not just smaller but also not as bulky.[1]

Paleobiology

With its similar morphology and relatively young age, it is assumed that Macronectes tinae was likely similar in lifestyle to the modern species of giant petrels. The reason for this species' less bulky build may be twofold. For one, it reflects the fact that giant petrels evolved from much smaller birds, as the genus' closest relatives are all much smaller than species in Macronectes. Furthermore, the difference in size may be related to the fact that M. tinae lived in warmer waters compared to the modern forms. This later explanation is however not ideal, as giant petrels are known to venture into warmer waters, especially in their youth.

Today giant petrels subsist themselves with a scavenging and hunting lifestyle, feeding on the carcasses found near seal or penguin colonies, feeding on chicks of other sea birds or hunting a variety of marine life including fish and cephalopods. Their dietary needs would be met by the fauna present in the Tangahoe Formation, which was home to the monk seal Eomonachus belegaerensis, the penguin Eudyptes atatu, an undescribed species of pelagornithid, the albatross Aldiomedes angustirostris and two smaller species of petrels.[1]

References

- Tennyson, A.J.D.; Salvador, R.B. (2023). "A New Giant Petrel (Macronectes, Aves: Procellariidae) from the Pliocene of Taranaki, New Zealand". Taxonomy. 3 (1): 57–67. doi:10.3390/taxonomy3010006.