Lymphangioma

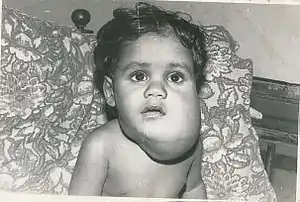

Lymphangiomas are malformations of the lymphatic system characterized by lesions that are thin-walled cysts; these cysts can be macroscopic, as in a cystic hygroma, or microscopic.[1] The lymphatic system is the network of vessels responsible for returning to the venous system excess fluid from tissues as well as the lymph nodes that filter this fluid for signs of pathogens. These malformations can occur at any age and may involve any part of the body, but 90% occur in children less than 2 years of age and involve the head and neck. These malformations are either congenital or acquired. Congenital lymphangiomas are often associated with chromosomal abnormalities such as Turner syndrome, although they can also exist in isolation. Lymphangiomas are commonly diagnosed before birth using fetal ultrasonography. Acquired lymphangiomas may result from trauma, inflammation, or lymphatic obstruction.

| Lymphangioma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lymphangioma (cystic hygroma) | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Most lymphangiomas are benign lesions that result only in a soft, slow-growing, "doughy" mass. Since they have no chance of becoming malignant, lymphangiomas are usually treated for cosmetic reasons only. Rarely, impingement upon critical organs may result in complications, such as respiratory distress when a lymphangioma compresses the airway. Treatment includes aspiration, surgical excision, laser and radiofrequency ablation, and sclerotherapy.

Signs and symptoms

There are three distinct types of lymphangioma, each with their own symptoms. They are distinguished by the depth and the size of abnormal lymph vessels, but all involve a malformation of the lymphic system. Lymphangioma circumscriptum can be found on the skin's surface, and the other two types of lymphangiomas occur deeper under the skin.

- Lymphangioma circumscriptum, a microcystic lymphatic malformation, resembles clusters of small blisters ranging in color from pink to dark red.[2] They are benign and do not require medical treatment, although some patients may choose to have them surgically removed for cosmetic reasons.

- Cavernous lymphangiomas are generally present at birth, but may appear later in the child's life.[3] These bulging masses occur deep under the skin, typically on the neck, tongue and lips,[4] and vary widely in size, ranging from as small as a centimeter in diameter to several centimeters wide. In some cases, they may affect an entire extremity such as a hand or foot. Although they are usually painless, the patient may feel mild pain when pressure is exerted on the area. They come in the colors white, pink, red, blue, purple, and black; and the pain lessens the lighter the color of the bump.

- Cystic hygroma shares many commonalities with cavernous lymphangiomas, and some doctors consider them to be too similar to merit separate categories. However, cystic lymphangiomas usually have a softer consistency than cavernous lymphangiomas, and this term is typically the one that is applied to lymphangiomas that develop in fetuses. They usually appear on the neck (75%), arm pit or groin areas. They often look like swollen bulges underneath the skin.

Causes

The direct cause of lymphangioma is a blockage of the lymphatic system as a fetus develops, although symptoms may not become visible until after the baby is born. The cause remains unknown. Why the embryonic lymph sacs remain disconnected from the rest of the lymphatic system is also not known.[4]

Cystic lymphangioma that emerges during the first two trimesters of pregnancy is associated with genetic disorders such as Noonan syndrome and trisomies 13, 18, and 21. Chromosomal aneuploidy such as Turner syndrome or Down syndrome[5] were found in 40% of patients with cystic hygroma.[6]

Pathophysiology

In 1976, Whimster studied the pathogenesis of lymphangioma circumscriptum, finding lymphatic cisterns in the deep subcutaneous plane are separated from the normal network of lymph vessels. They communicate with the superficial lymph vesicles through vertical, dilated lymph channels. Whimster theorized the cisterns might come from a primitive lymph sac that failed to connect with the rest of the lymphatic system during embryonic development.

A thick coat of muscle fibers that cause rhythmic contractions line the sequestered primitive sacs. Rhythmic contractions increase the intramural pressure, causing dilated channels to come from the walls of the cisterns toward the skin. He suggested that the vesicles seen in lymphangioma circumscriptum are outpouchings of these dilated projecting vessels. Lymphatic and radiographic studies support Whimsters observations. Such studies reveal that big cisterns extend deeply into the skin and beyond the clinical lesions. Lymphangiomas that are deep in the dermis show no evidence of communication with the regular lymphatics. The cause for the failure of lymph sacs to connect with the lymphatic system is not known.[4]

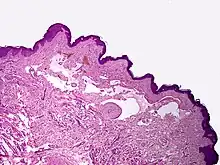

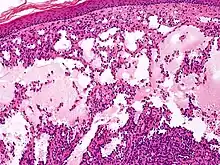

Microscopically, the vesicles in lymphangioma circumscriptum are greatly dilated lymph channels that cause the papillary dermis to expand. They may be associated with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis. There are many channels in the upper dermis which often extend to the subcutis (the deeper layer of the dermis, containing mostly fat and connective tissue). The deeper vessels have large calibers with thick walls which contain smooth muscle. The lumen is filled with lymphatic fluid, but often contains red blood cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. The channels are lined with flat endothelial cells. The interstitium has many lymphoid cells and shows evidence of fibroplasia (the formation of fibrous tissue). Nodules (A small mass of tissue or aggregation of cells) in cavernous lymphangioma are large, irregular channels in the reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissue that are lined by a single layer of endothelial cells. Also an incomplete layer of smooth muscle also lines the walls of these channels. The stroma consists of loose connective tissue with a lot of inflammatory cells. These tumors usually penetrate muscle. Cystic hygroma is indistinguishable from cavernous lymphangiomas on histology.[4]

The typical history of Lymphangioma circumscriptum shows a small number of vesicles on the skin at birth or shortly after. In subsequent years, they tend to increase in number, and the area of skin involved continues to expand. Vesicles or other skin abnormalities may not be noticed until several years after birth. Usually, lesions are asymptomatic or do not show any evidence of a disease, but, mostly, patients may have random break outs of some bleeding and major drainage of clear fluid from ruptured vesicles.

Cavernous lymphangioma first appears during infancy, when a rubbery nodule with no skin changes becomes obvious in the face, trunk, or extremity. These lesions often grow at a rapid pace, similar to that of raised hemangiomas. No family history of prior lymphangiomas is described.

Cystic hygroma causes deep subcutaneous cystic swelling, usually in the axilla, base of the neck, or groin, and is typically noticed soon after birth. If the lesions are drained, they will rapidly fill back up with fluid. The lesions will grow and increase to a larger size if they are not completely removed in surgery.[4]

Diagnosis

Cases of lymphangioma are diagnosed by histopathologic inspection.[7] In prenatal cases, lymphangioma is diagnosed during the late first trimester or early second trimester using an ultrasound. Other imaging methods such as CT and MRI scans are useful in treatment planning, delineate the size of the lesion, and determine its surrounding vital structures. T2-weight MRI is useful to differentiate lymphangioma from surrounding structures due to its high T2 signal.[8]

Classification

Lymphangiomas have traditionally been classified into three subtypes: capillary and cavernous lymphangiomas and cystic hygroma. This classification is based on their microscopic characteristics. A fourth subtype, the hemangiolymphangioma is also recognized.[9]

- Capillary lymphangiomas

- Capillary lymphangiomas are composed of small, capillary-sized lymphatic vessels and are characteristically located in the epidermis.

- Cavernous lymphangiomas

- Composed of dilated lymphatic channels, cavernous lymphangiomas characteristically invade surrounding tissues.

- Cystic hygromas

- Cystic hygromas are large, macrocystic lymphangiomas filled with straw-colored, protein-rich fluid.

- Hemangiolymphangioma

- As suggested by their name, hemangiolymphangiomas are lymphangiomas with a vascular component.

Lymphangiomas may also be classified into microcystic, macrocystic, and mixed subtypes, according to the size of their cysts.[9]

- Microcystic lymphangiomas

- Microcystic lymphangiomas are composed of cysts, each of which measures less than 2 cm3 in volume.

- Macrocystic lymphangiomas

- Macrocystic lymphangiomas contain cysts measuring more than 2 cm3 in volume.

- Mixed lymphangiomas

- Lymphangiomas of the mixed type contain both microcystic and macrocystic components.

Finally, lymphangiomas may be described in stages, which vary by location and extent of disease. In particular, stage depends on whether lymphangiomas are present above or superior to the hyoid bone (suprahyoid), below or inferior to the hyoid bone (infrahyoid), and whether the lymphangiomas are on one side of the body (unilateral) or both (bilateral).[9]

- Stage I

- Unilateral infrahyoid.

- Stage II

- Unilateral suprahyoid.

- Stage III

- Unilateral suprahyoid and infrahyoid.

- Stage IV

- Bilateral suprahyoid.

- Stage V

- Bilateral suprahyoid and infrahyoid.

Treatment

Treatment for cystic hygroma involves the removal of the abnormal tissue; however complete removal may be impossible without removing other normal areas. Surgical removal of the tumor is the typical treatment provided, with the understanding that additional removal procedures will most likely be required as the lymphangioma grows. Most patients need at least two procedures done for the removal process to be achieved. Recurrence is possible but unlikely for those lesions able to be removed completely via excisional surgery.[10] Radiotherapy and chemical cauteries are not as effective with the lymphangioma than they are with the hemangioma.[11] Draining lymphangiomas of fluid provides only temporary relief, so they are removed surgically. Cystic Hygroma can be treated with OK432 (Picibanil).

The least invasive and most effective form of treatment is now performed by interventional radiologists. A sclerosing agent, such as 1% or 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate, doxycycline, or ethanol, may be directly injected into a lymphocele. "All sclerosing agents are thought to work by ablating the endothelial cells of the disrupted lymphatics feeding into the lymphocele."[12]

Lymphangioma circumscription can be healed when treated with a flashlamp pulsed dye laser, although this can cause port-wine stains and other vascular lesions.[13]

Orbital lymphangiomas, which carry significant risks from surgical removal, can also be treated with sclerosing agents, systemic medication, or through observation.[14]

Sirolimus

Sirolimus is used to treat lymphangioma . Treatment with sirolimus can decrease pain and the fullness of venous malformations, improve coagulation levels, and slow the growth of abnormal lymphatic vessels. [15] Sirolimus is a relatively new medical therapy for the treatment of vascular malformations, [16] in recent years, sirolimus has emerged as a new medical treatment option for both vascular tumors and vascular malformations, as a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), capable of integrating signals from the PI3K/AKT pathway to coordinate proper cell growth and proliferation. [17] Sirolimus (rapamycin, trade name Rapamune) is a macrolide compound. It has immunosuppressant and antiproliferative functions in humans. It inhibits activation of T cells and B cells by reducing their sensitivity to interleukin-2 (IL-2) through mTOR inhibition.[18]

Prognosis

The prognosis for lymphangioma circumscriptum and cavernous lymphangioma is generally excellent. This condition is associated with minor bleeding, recurrent cellulitis, and lymph fluid leakage. Two cases of lymphangiosarcoma arising from lymphangioma circumscriptum have been reported; however, in both of the patients, the preexisting lesion was exposed to extensive radiation therapy.

In cystic hygroma, large cysts can cause dysphagia, respiratory problems, and serious infection if they involve the neck. Patients with cystic hygroma should receive cytogenetic analysis to determine if they have chromosomal abnormalities, and parents should receive genetic counseling because this condition can recur in subsequent pregnancies.[4]

Complications after surgical removal of cystic hygroma include damage to the structures in the neck, infection, and return of the cystic hygroma.[10]

Epidemiology

Lymphangiomas are rare, accounting for 4% of all vascular tumors in children.[4] Although lymphangioma can become evident at any age, 50% are seen at birth,[9] and 90% of lymphangiomas are evident by 2 years of age.[9]

History

In 1828, Redenbacher first described a lymphangioma lesion. In 1843, Wernher gave the first case report of a cystic hygroma, from the Greek "hygro-" meaning fluid and "oma" meaning tumor. In 1965, Bill and Summer proposed that Cystic hygromas and lymphangiomas are variations of a single entity and that its location determines its classification.

References

- Sheddy, Aditya; D'Souza, Donna. "Lymphangioma". Radiopaedia. UBM Medica network. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Boudaya S, et al. (2007). "Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva". Dermatology Online Journal. 13 (4): 10. doi:10.5070/D387R7T9TC. PMID 18319007.

- A.D.A.M (2007-09-26). "Lymphangioma". Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- Fernandez, Geover; Robert A Schwartz (2008). "Lymphangioma". WebMD LLC. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- Gedikbasi, Ali; Gul, Ahmet; Sargin, Akif; Ceylan, Yavuz (November 2007), "Cystic hygroma and lymphangioma: associated findings, perinatal outcome and prognostic factors in live-born infants", Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 276 (5): 491–498, doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0364-y, ISSN 0932-0067, PMID 17429667, S2CID 26084111

- Shulman LP, Emerson DS, Felker RE, Phillips OP, Simpson JL, Elias S (July 1992). "High frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities in fetuses with cystic hygroma diagnosed in the first trimester". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 80 (1): 80–2. PMID 1603503.

- Laskaris, George (2003). Color atlas of oral diseases. Thieme. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-58890-138-5.

- Ha, Jennifer; Yu, Yu-Ching; Lannigan, Francis (2014-08-05). "A Review of the Management of Lymphangiomas". Current Pediatric Reviews. 10 (3): 238–248. doi:10.2174/1573396309666131209210751. PMID 25088344.

- Giguère CM, Bauman NM, Smith RJ (December 2002). "New treatment options for lymphangioma in infants and children". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 111 (12 Pt 1): 1066–75. doi:10.1177/000348940211101202. PMID 12498366. S2CID 23946071.

- O’Reilly, Deirdre (2008). "Lymphangioma". Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- Goldberg; Kennedy (1997). "Lymphangioma". Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- Handbook of Interventional Radiologic Procedures. Third Edition. Krishna Kandarpa, and John Aruny. Lippincott 2002.

- Weingold DH, White PF, Burton CS (May 1990). "Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with tunable dye laser". Cutis. 45 (5): 365–6. PMID 2357907.

- Patel SR, Rosenberg JB, Barmettler A (2019). "Interventions for orbital lymphangioma". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5 (5): CD013000. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013000.pub2. PMC 6521140. PMID 31094450.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Venous Malformation | Treatments | Boston Children's Hospital".

- Dekeuleneer, Valérie, et al. "Theranostic Advances in Vascular Malformations." Journal of Investigative Dermatology 140.4 (2020): 756-763.

- Lee, Byung-Boong. "Sirolimus in the treatment of vascular anomalies." https://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741-5214(19)32236-0/fulltext, Journal of Vascular Surgery 71.1 (2020): 328.

- Mukherjee S, Mukherjee U (2009-01-01). "A comprehensive review of immunosuppression used for liver transplantation". Journal of Transplantation. 2009: 701464. doi:10.1155/2009/701464. PMC 2809333. PMID 20130772.