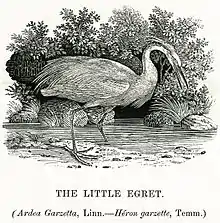

Little egret

The little egret (Egretta garzetta) is a species of small heron in the family Ardeidae. It is a white bird with a slender black beak, long black legs and, in the western race, yellow feet. As an aquatic bird, it feeds in shallow water and on land, consuming a variety of small creatures. It breeds colonially, often with other species of water birds, making a platform nest of sticks in a tree, bush or reed bed. A clutch of three to five bluish-green eggs is laid and incubated by both parents for about three weeks. The young fledge at about six weeks of age.

| Little egret | |

|---|---|

_Photograph_by_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg.webp) | |

| E. g. garzetta

Mangaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Egretta |

| Species: | E. garzetta |

| Binomial name | |

| Egretta garzetta (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

E. g. garzetta | |

| |

| Range of E. garzetta Breeding Resident Non-breeding Vagrant (seasonality uncertain) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ardea garzetta Linnaeus, 1766 | |

Its breeding distribution is in wetlands in warm temperate to tropical parts of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. A successful colonist, its range has gradually expanded north, with stable and self-sustaining populations now present in the United Kingdom.[2]

In warmer locations, most birds are permanent residents; northern populations, including many European birds, migrate to Africa and southern Asia to over-winter there. The birds may also wander north in late summer after the breeding season, and their tendency to disperse may have assisted in the recent expansion of the bird's range. At one time common in Western Europe, it was hunted extensively in the 19th century to provide plumes for the decoration of hats and became locally extinct in northwestern Europe and scarce in the south. Around 1950, conservation laws were introduced in southern Europe to protect the species and their numbers began to increase. By the beginning of the 21st century the bird was breeding again in France, the Netherlands, Ireland and Britain. Its range is continuing to expand westward, and the species has begun to colonise the New World; it was first seen in Barbados in 1954 and first bred there in 1994. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed the bird's global conservation status as being of "least concern".

Taxonomy

The little egret was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1766 in the twelfth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Ardea garzetta.[3] It is now placed with 12 other species in the genus Egretta that was introduced in 1817 by the German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster with the little egret as the type species.[4][5] The genus name comes from the Provençal French Aigrette, "egret", a diminutive of Aigron, "heron". The species epithet garzetta is from the Italian name for this bird, garzetta or sgarzetta.[6]

Two subspecies are recognised:[5]

- E. g. garzetta (Linnaeus, 1766) – nominate, found in Europe, Africa, and most of Asia except the south-east

- E. g. nigripes (Temminck, 1840) – found in the Sunda Islands, Australia and New Zealand

Three other egret taxa have at times been classified as subspecies of the little egret in the past but are now regarded as two separate species. These are the western reef heron Egretta gularis which occurs on the coastline of West Africa (Egretta gularis gularis) and from the Red Sea to India (Egretta gularis schistacea), and the dimorphic egret (Egretta dimorpha), found in East Africa, Madagascar, the Comoros and the Aldabra Islands.[7]

Description

_in_flight_Cyprus.jpg.webp)

The adult little egret is 55–65 cm (22–26 in) long with an 88–106 cm (35–42 in) wingspan, and weighs 350–550 g (12–19 oz). Its plumage is normally entirely white, although there are dark forms with largely bluish-grey plumage.[8] In the breeding season, the adult has two long plumes on the nape that form a crest. These plumes are about 150 mm (6 in) and are pointed and very narrow. There are similar feathers on the breast, but the barbs are more widely spread. There are also several elongated scapular feathers that have long loose barbs and may be 200 mm (8 in) long. During the winter the plumage is similar but the scapulars are shorter and more normal in appearance. The bill is long and slender and it and the lores are black. There is an area of greenish-grey bare skin at the base of the lower mandible and around the eye which has a yellow iris. The legs are black and the feet yellow. Juveniles are similar to non-breeding adults but have greenish-black legs and duller yellow feet,[9] and may have a certain proportion of greyish or brownish feathers.[8] The subspecies nigripes differs in having yellow skin between the bill and eye, and blackish feet. During the height of courtship, the lores turn red and the feet of the yellow-footed races turn red.[8]

Little egrets are mostly silent but make various croaking and bubbling calls at their breeding colonies and produce a harsh alarm call when disturbed. To the human ear, the sounds are indistinguishable from the black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) with which it sometimes associates.[9]

Distribution and habitat

The breeding range of the western race (E. g. garzetta) includes southern Europe, the Middle East, much of Africa and southern Asia. Northern European populations are migratory, mostly travelling to Africa although some remain in southern Europe, while some Asian populations migrate to the Philippines. The eastern race, (E. g. nigripes), is resident in Indonesia and New Guinea, while E. g. immaculata inhabits Australia and New Zealand, but does not breed in the latter.[8] During the late twentieth century, the range of the little egret expanded northwards in Europe and into the New World, where a breeding population was established on Barbados in 1994. The birds have since spread elsewhere in the Caribbean region and on the Atlantic coast of the United States.[10]

The little egret's habitat varies widely, and includes the shores of lakes, rivers, canals, ponds, lagoons, marshes and flooded land, the bird preferring open locations to dense cover. On the coast it inhabits mangrove areas, swamps, mudflats, sandy beaches and reefs. Rice fields are an important habitat in Italy, and coastal and mangrove areas are important in Africa. The bird often moves about among cattle or other hoofed mammals.[8]

Behaviour

Little egrets are sociable birds and are often seen in small flocks. Nevertheless, individual birds do not tolerate others coming too close to their chosen feeding site, though this depends on the abundance of prey.

Food and feeding

They use a variety of methods to procure their food; they stalk their prey in shallow water, often running with raised wings or shuffling their feet to disturb small fish, or may stand still and wait to ambush prey. They make use of opportunities provided by cormorants disturbing fish or humans attracting fish by throwing bread into water. On land they walk or run while chasing their prey, feed on creatures disturbed by grazing livestock and ticks on the livestock, and even scavenge. Their diet is mainly fish, but amphibians, small reptiles, mammals and birds are also eaten, as well as crustaceans, molluscs, insects, spiders and worms.[8]

Breeding

Little egrets nest in colonies, often with other wading birds. On the coasts of western India these colonies may be in urban areas, and associated birds include cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis), black-crowned night herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) and black-headed ibises (Threskiornis melanocephalus). In Europe, associated species may be squacco herons (Ardeola ralloides), cattle egrets, black-crowned night herons and glossy ibises (Plegadis falcinellus). The nests are usually platforms of sticks built in trees or shrubs, or in reed beds or bamboo groves. In some locations such as the Cape Verde Islands, the birds nest on cliffs. Pairs defend a small breeding territory, usually extending around 3 to 4 m (10 to 13 ft) from the nest. The three to five eggs are incubated by both adults for 21 to 25 days before hatching. They are oval in shape and have a pale, non-glossy, blue-green shell colour. The young birds are covered in white down feathers, are cared for by both parents and fledge after 40 to 45 days.[8][9]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) juvenile

juvenile.jpg.webp) feeding juvenile

feeding juvenile

Conservation

Globally, the little egret is not listed as a threatened species and has in fact expanded its range over the last few decades.[7] The International Union for Conservation of Nature states that their wide distribution and large total population means that they are a species that cause them "least concern".[1]

Status in northwestern Europe

Historical research has shown that the little egret was once present, and probably common, in Ireland and Great Britain, but became extinct there through a combination of over-hunting in the late medieval period and climate change at the start of the Little Ice Age.[11] The inclusion of 1,000 egrets (among numerous other birds) in the banquet to celebrate the enthronement of George Neville as Archbishop of York at Cawood Castle in 1465 indicates the presence of a sizable population in northern England at the time, and they are also listed in the coronation feast of King Henry VI in 1429.[12][13] They had become scarce by the mid-16th century, when William Gowreley, "yeoman purveyor to the Kinges mowthe", "had to send further south" for egrets.[13] In 1804 Thomas Bewick commented that if it were the same bird as listed in Neville's bill of fare "No wonder this species has become nearly extinct in this country!"[14]

Further declines occurred throughout Europe as the plumes of the little egret and other egrets were in demand for decorating hats. They had been used in the plume trade since at least the 17th century but in the 19th century it became a major craze and the number of egret skins passing through dealers reached into the millions.[15] Complete statistics do not exist, but in the first three months of 1885, 750,000 egret skins were sold in London, while in 1887 one London dealer sold 2 million egret skins.[16] Egret farms were set up where the birds could be plucked without being killed but most of the supply of so-called "Osprey plumes"[17] was obtained by hunting, which reduced the population of the species to dangerously low levels and stimulated the establishment of Britain's Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in 1889.[15]

By the 1950s, the little egret had become restricted to southern Europe, and conservation laws protecting the species were introduced. This allowed the population to rebound strongly; over the next few decades it became increasingly common in western France and later on the north coast. It bred in the Netherlands in 1979 with further breeding from the 1990s onward. About 22,700 pairs are thought to breed in Europe, with populations stable or increasing in Spain, France and Italy but decreasing in Greece.[18]

In Britain it was a rare vagrant from its 16th-century disappearance until the late 20th century, and did not breed. It has however recently become a regular breeding species and is commonly present, often in large numbers, at favoured coastal sites. The first recent breeding record in England was on Brownsea Island in Dorset in 1996, and the species bred in Wales for the first time in 2002.[19] The population increase has been rapid subsequently, with over 750 pairs breeding in nearly 70 colonies in 2008,[20] and a post-breeding total of 4,540 birds in September 2008.[21] The first record of breeding in Scotland happened in 2020 in Dumfries & Galloway.[22] In Ireland, the species bred for the first time in 1997 at a site in County Cork and the population has also expanded rapidly since, breeding in most Irish counties by 2010. Severe winter weather in 2010–2012 proved to be only a temporary setback, and the species continues to spread.[23]

Status in Australia

In Australia, its status varies from state to state. It is listed as "Threatened" on the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988.[24] Under this act, an Action Statement for the recovery and future management of this species has been prepared.[25] On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the little egret is listed as endangered.[26]

Colonisation of the New World

With its range continuing to expand, the little egret has now started to colonise the New World. The first record there was on Barbados in April 1954. The bird began breeding on the island in 1994 and now also breeds in the Bahamas.[18] Ringed birds from Spain provide a clue to the birds' origin.[10] The birds are very similar in appearance to the snowy egret and share colonial nesting sites with these birds in Barbados, where they are both recent arrivals. The little egrets are larger, have more varied foraging strategies and exert dominance over feeding sites.[10]

Little egrets are seen with increasing regularity over a wider area and have been observed from Suriname and Brazil in the south to Newfoundland, Quebec and Ontario in the north. Birds on the east coast of North America are thought to have moved north with snowy egrets from the Caribbean. In June 2011, a little egret was spotted in Maine, in the Scarborough Marsh, near the Audubon Center.[27]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Egretta garzetta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T62774969A86473701. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T62774969A86473701.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Lock, Leigh; Cook, Kevin. "The Little Egret in Britain: a successful colonist" (PDF). britishbirds.co.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1766). Systema naturae : per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 1 (12th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 237.

- Forster, T. (1817). A Synoptical Catalogue of British Birds; intended to identify the species mentioned by different names in several catalogues already extant. Forming a book of reference to Observations on British ornithology. London: Nichols, son, and Bentley. p. 59.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Ibis, spoonbills, herons, Hamerkop, Shoebill, pelicans". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 143, 171. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A.; Sargatal, J., eds. (1992). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 412. ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- Hancock, James; Kushlan, James A. (2010). The Herons Handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 175–180. ISBN 978-1-4081-3496-2.

- Witherby, H. F., ed. (1943). Handbook of British Birds, Volume 3: Hawks to Ducks. H. F. and G. Witherby Ltd. pp. 139–142.

- Kushlan James A. (2007). "Sympatric Foraging of Little Egrets and Snowy Egrets in Barbados, West Indies". Waterbirds. 30 (4): 609–612. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2007)030[0609:sfolea]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 25148265. S2CID 85785862.

- Colton, Stephen (August 13, 2016). "A shower of white fire: celebrating the Little Egret". The Irish News.

- Stubbs, F.J. (1910). "The Egret in Britain". Zoologist. 14 (4): 310–311.

- Bourne, W.R.P. (2003). "Fred Stubbs, Egrets, Brewes and climatic change". British Birds. 96: 332–339.

- Bewick, Thomas (1847) [1804]. A History of British Birds, Volume II, "Water Birds". R. E. Bewick. p. 44.

- Haines, Perry (20 August 2002). "History repeats, once again RSPB fights the cause of the Little Egret". BirdGuides. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus. p. 50. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

- "Birds and Millinery". Bird Notes and News. 2 (1): 29. 1906.

- "Little egret". Avibirds. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "UK RSPB information on the Little Egret spread into Britain". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- Holling, M.; et al. (2010). "Rare breeding birds in the United Kingdom in 2008" (PDF). British Birds. 103: 482–538.

- Calbrade, N.; et al. (2010). Waterbirds in the UK 2008/09. The Wetland Bird Survey. ISBN 978-1-906204-33-4.

- B. Mearns; R. Mearns (2020). "The first confirmed breeding of Little Egret in Scotland 2020". Scottish Birds. 40 (4): 305–306.

- Report of the Irish Rare Birds Breeding Panel 2013 Irish Birds Vol. 10 p.65

- "Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act – Listed Taxa, Communities and Potentially Threatening Processes". Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011.

- "Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act: Index of Approved Action Statements". Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008.

- Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria – 2007. East Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Sustainability and Environment. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-74208-039-0.

- "Rare Bird Flies Into Scarborough". Wmtw.com. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

External links

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Little Egret – The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- BirdLife species factsheet for Egretta garzetta

- "Little egret media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Little egret photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Audio recordings of Little egret on Xeno-canto.

_feeding_Cyprus_1.jpg.webp)

_feeding_Cyprus_2.jpg.webp)