Brownsea Island

Brownsea Island is the largest of the islands in Poole Harbour in the county of Dorset, England. The island is owned by the National Trust with the northern half managed by the Dorset Wildlife Trust. Much of the island is open to the public and includes areas of woodland and heath with a wide variety of wildlife, together with cliff top views across Poole Harbour and the Isle of Purbeck.

| Brownsea Island | |

|---|---|

The castle and piers on Brownsea Island | |

Brownsea Island Location within Dorset | |

| OS grid reference | SZ019879 |

| Civil parish | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | POOLE |

| Postcode district | BH13 |

| Dialling code | 01202 |

| Police | Dorset |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

The island was the location of an experimental camp in 1907 that led to the formation of the Scout movement the following year. Access is by public ferry or private boat; in 2017 the island received 133,340 visitors.[1] The island's name probably comes from Old English Brūnoces īeg = "Brūnoc's island".[2]

Geography

Brownsea Island lies in Poole Harbour opposite the town of Poole in Dorset, England. It is the largest of eight islands in the harbour. The island can be reached by one of the public ferries or by private boat. There is a wharf and a small dock near the main castle. The island is 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) long and 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) wide and consists of 500 acres (200 ha) of woodland (pine and oak), heathland and salt-marsh.[3]

The entire island, except the church and a few other buildings which are leased or managed by third parties, is owned by the National Trust. Most of the buildings are situated near the small landing stage. The northern portion of the island is a Nature Reserve managed by Dorset Wildlife Trust and an important habitat for birds; this part of the island has limited public access. A small portion to the southeast of the island, along with Brownsea Castle, is leased to the John Lewis Partnership for use as a holiday hotel by partners, and is not open to the public.

The island forms part of the Studland civil parish within the Dorset unitary authority. It is within the South Dorset constituency of the House of Commons. Until 31 January 2020, it was also within the South West England constituency of the European Parliament.[4][5]

Ecology

Brownsea Island has built up on a bare sand and mud bank deposited in the shallow harbour. Ecological succession has taken place on the island to create topsoil able to support ecosystems.

The nature reserve on the island is leased from the National Trust by Dorset Wildlife Trust. This reserve includes a brackish lagoon and area of woodland. Other ecosystems on the island include salt marsh, reedbed, two freshwater lakes, alder carr, coniferous woodland, deciduous woodland and arboretum. In the past invasive species such as rhododendrons, also non-native, were introduced to the island, but the trusts have cleared many areas.[6] The entire island is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Wildlife

The island is one of the few places in southern England where indigenous red squirrels survive, largely because non-native grey squirrels have never been introduced to the island. The Brownsea red squirrel population is the only population known in the UK to carry the human form of the bacteria stem Mycobacterium leprae that causes leprosy in humans.[7] Brownsea also has a small ornamental population of peacocks. The island has a heronry, in which both grey heron and little egret nest.

There is a large population of non-native sika deer on the island. In the past the numbers have been higher than the island can sustain and have overgrazed. To try to limit damage to trees and other vegetation by deer, areas of the island have been fenced off to provide areas of undamaged woodland to allow other species such as red squirrels to thrive.

The lagoon is noted for the large population of common tern and sandwich tern in summer, and a very large flock of avocets in winter, when more than 50 per cent of the British population (over 1500) can be present.

Some imported stonework and statuary on the island serves as a habitat for a Mediterranean land snail, Papillifera bidens.[8]

History

Early history

The first records of inhabitants on Brownsea Island occurred in the 9th century, when a small chapel and hermitage were built by monks from Cerne Abbey near Dorchester. The chapel was dedicated to St Andrew and the only resident of the island was a hermit, who may have administered to the spiritual welfare of sailors passing through Poole Harbour. In 1015, Canute led a Viking raid to the harbour and used Brownsea as a base to sack Wareham and Cerne Abbey.[9] In the 11th century the owner of the island was Bruno, who was Lord of the Manor of Studland.[9] Following his invasion of England, William the Conqueror gave Studland, which included Brownsea, to his half-brother, Robert de Mortain. In 1154, King Henry II granted the Abbot of Cerne the right of wreck for the island and the abbey continued to control the interests of Brownsea for the following 350 years.[10]

Tudor period and Civil War

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, control of Brownsea passed to the Crown. Henry VIII recognised the island's strategic importance of guarding the narrow entrance to the expanding port of Poole. As part of a deterrent to invasion forces from Europe, the island was fortified in 1547 by means of a blockhouse, which became known as Brownsea Castle. In the following centuries, the island passed into the hands of a succession of various owners.

In 1576, Queen Elizabeth I made a gift of Brownsea to one of her court favourites and rumoured lover, Sir Christopher Hatton.[11] During the English Civil War, Poole sided with Parliament and garrisoned Brownsea Castle. Colonel Thomas Pride, the instigator of Pride's Purge– the only military coup d'état in English history – was stationed on the island in 1654.[12] Sir Robert Clayton, a Lord Mayor of the City of London and wealthy merchant became owner in the mid-1650s and after his death in 1707 the island was sold to William Benson, a Whig Member of Parliament and architect. He converted the castle into a residence and was responsible for introducing many varieties of trees to the island.[13]

Industrial plans

In 1765 Sir Humphrey Sturt, a local landowner and MP purchased the island, which in turn passed to his sons. Sturt expanded the castle and records suggest that he spent £50,000 on enhancing the island's gardens.[14] Sir Augustus John Foster, a retired British diplomat, bought the island in 1840. Foster experienced bouts of depression and died in Brownsea Castle in 1848 when he slit his throat.[15] In 1852 Brownsea was again up for sale and was sold for £13,000. It was purchased by William Waugh, a former Colonel in the British Army in the belief he could exploit the white clay deposits on the island to manufacture high-quality porcelain.[16]

A three-storey pottery was built in southwest corner of the island together with a tramway to transport the clay from clay pits in the north. He hoped the clay would be of the same quality as the nearby Furzebrook clay, but it turned out to be suitable only for sanitary ware. The company employed more than 200 people, but by 1887 the venture closed owing to a lack of demand and the poor quality of the clay.[17]

Traces of these activities remain today, mainly as building foundations and pottery fragments. Waugh was also responsible for expanding the number of buildings on the island – creating the now ruined village of Maryland (named after Waugh's wife), as well as adding a new gatehouse and tower in the Tudor style. Waugh also paid for the construction of a new pier, adorned with castellated watch towers. Another large expenditure was the construction of St Mary's church, built in the Gothic style, and also named after his wife. The foundation stone was laid by Sir Harry Smith in 1853 and construction was completed a year later. Inside the church there is a monument to Waugh as well as the tomb of the late owner Charles van Raalte. Part of the church is dedicated to the Scouting movement and the flags of the Scout and Girl Guide movements line either side of the main altar.

After falling heavily into debt the Waughs fled to Spain. The island was acquired by creditors and sold in 1873 to George Cavendish-Bentinck, who added Jersey cows to Brownsea and expanded the island's agriculture. He filled the island with several Italian renaissance sculptures, some of which still decorate the church and the quay. The 1881 census recorded a total population of 270 people on the island, the majority of whom provided a labour force for the pottery works.[18] After his death, the island was sold to Kenneth Robert Balfour in 1891. Following the introduction of electric lighting, the castle was gutted by fire in 1896. It was subsequently rebuilt, and in 1901 Balfour put the island up for sale.[19]

20th century

The island was purchased by wealthy stockbroker Charles van Raalte who used the island as a residential holiday retreat. During this time the castle was renovated and served as host to famous visitors such as Guglielmo Marconi.[21] Robert Baden-Powell, a close friend of the van Raaltes, hosted an experimental camp for boys on the island in the summer of 1907. Brownsea was largely self-supporting, with a kitchen garden and a dairy herd. Many of the pottery factory workers had stayed on after it closed, farming and working for the owners.[22]

Charles van Raalte died in Calcutta in February, 1908 and his wife eventually sold the island in 1925. In 1927 it was purchased at auction by Mary Bonham-Christie for £125,000. A recluse by nature, she ordered a mass eviction of the island's residents to the mainland. Most of the island was abandoned and gradually reverted to natural heath and woodland. In 1934, a wild fire caused devastation after burning for a week. Much of the island was reduced to ashes, and the buildings to the east were only saved by a change of wind direction. Traumatised by the event, Bonham-Christie banned all public access to the island for the rest of her life.[23]

During the Second World War large flares were placed on the western end of the island to mislead Luftwaffe bombers away from the port of Poole. The decoy saved Poole and Bournemouth from 1,000 tonnes (160,000 st) of German bombs, but the deserted village of Maryland was destroyed.[24] In April 1961, Bonham-Christie died at 98 years old and her grandson gave the island to the Treasury to pay her death duties. Concerned the island could be sold to commercial developers, a campaign was started by local conservationist, Helen Brotherton, with the aim of purchasing the island to protect its natural habitats.

The National Trust subsequently agreed to take over responsibility for the island if enough funds were raised and in 1962 it purchased Brownsea for £100,000.[25] Work was carried out to prepare the island for visitors; tracks were cleared through areas overgrown with rhododendrons and firebreaks were created to prevent repetition of the 1934 fire. The Dorset Wildlife Trust leased a nature reserve on the north of the island, the Scout and Guide Movements were allowed to return and the castle was renovated and leased to the John Lewis Partnership for use as a staff hotel. The island was opened to the public in May 1963 by Olave, Lady Baden-Powell, the Chief Guide, at a ceremony attended by members of the 1907 camp. Soon after Brownsea Island was opened to the public, it was attracting more than 10,000 visitors a year.[26] Larger boats means that today the island attracts some 110,000 visitors annually.

Since 1964 the island has been host to the Brownsea Open Air Theatre, annually performing the works of William Shakespeare. The island has a visitor centre and museum, displaying the island's history. There is also a newly located shop and cafe, with one holiday cottage on the quay. At the Scout camp at the southwest of the Island there is an outdoor centre and a trading post shop which is focused on the Scout movement.

21st century

The Dorset Wildlife Trust operates on the island from The Villa, previously the island vicarage. The island has a single post box that is emptied each day. In October 2008, the island was featured on BBC One's annual Autumnwatch programme.[27]

There is an annual round-the-island swim of 4+1⁄2 miles (7.2 km) run by the RLSS Poole Lifeguards.[28]

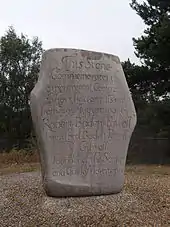

Scouting

From 1 August until 8 August 1907, Robert Baden-Powell held an experimental camp on the island, to test out his Scouting ideas. He gathered 21 boys of mixed social backgrounds (from boys' schools in the London area and a section of boys from the Poole, Parkstone, Hamworthy, Bournemouth, and Winton Boys' Brigade units) and held a week-long camp.[29] The boys took part in activities such as camping, observation, woodcraft, chivalry, lifesaving and patriotism. Following the successful camp, Baden-Powell published his first book on the Scouting movement in 1908, Scouting for Boys, and the international Scouting movement grew rapidly.[29]

Boy Scouts continued to camp on the island until the 1930s, when all public access to the island was forbidden by the island's owner. After ownership of the island transferred to the National Trust, a permanent 20 hectares (49 acres) Scout camp site was opened in 1963 by Olave Baden-Powell.

In August 2007, 100 years after the first experimental camp, Brownsea Island was the focus of worldwide celebrations of the centenary of Scouting. Four camps were set up on the island including a replica of the original 1907 camp, and hundreds of Scouts and Girl Guides from 160 countries travelled to the island to take part in the celebrations.[30] Also present on the Island that day were 17 descendants of Baden-Powell.

References

Notes

- "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Brownsea Island Key to English Place-names". The University of Nottingham. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Brownsea Island National Trust guide, 1993

- OS Explorer Map OL15 – Purbeck & South Dorset. Ordnance Survey. 2006. ISBN 978-0-319-23865-3.

- "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Steven Morris (8 September 2011). "Brownsea Island red squirrel population at capacity". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "UK red squirrels carry 'a form of leprosy' - scientists". BBC News. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Snail at Brownsea and Clivedon due to 'Victorian bling'". BBC News. 26 August 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- Sydenham (p.384)

- Sydenham (p.385)

- Legg (p.28)

- Legg (p.33)

- Legg (p.37–38)

- Legg (p.41)

- Legg (p.58)

- "Grand industrial plans". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Part 3 – Mining and quarrying on Brownsea Island". University of Southampton. 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Legg (p.72)

- "Agriculture and art". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Betty Clay | 1964 - 1974 England".

- "Marconi, a favourite guest". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Ordinary life on the island". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Legg (p.108)

- Legg (p.118)

- Legg (p.130)

- Legg (p.30)

- "Nature UK: Homepage of Springwatch and Autumnwatch". BBC. 2 November 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Brownsea Swim 2014 Details - RLSS Poole Lifeguard". Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- Woolgar, Brian; La Riviere, Sheila (2002). Why Brownsea? The Beginnings of Scouting. Brownsea Island Scout and Guide Management Committee (re-issue 2007, Wimborne Minster: Minster Press). ISBN 1-899499-16-4.

- "Scouts in centenary celebrations". BBC News. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Dorset Twinning Association List". The Dorset Twinning Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Dorset County Council, Visitor Numbers at Selected Attractions 1998 to 2002.

- National Trust (See External links).

- Pitt-Rivers, Michael, 1970. Dorset. London: Faber & Faber.

Bibliography

- Bugler, John; Drew, Gregory (1995). A history of Brownsea Island. Dorset County Library. ISBN 0852167652.

- Legg, Rodney (2005). The Book of Poole Harbour and Town. Halsgrove. ISBN 1-84114-411-8.

- Sydenham, John (1986) [1839]. The History of the Town and County of Poole (2nd ed.). Poole: Poole Historical Trust. ISBN 0-9504914-4-6.