List of Quaternary volcanic eruptions

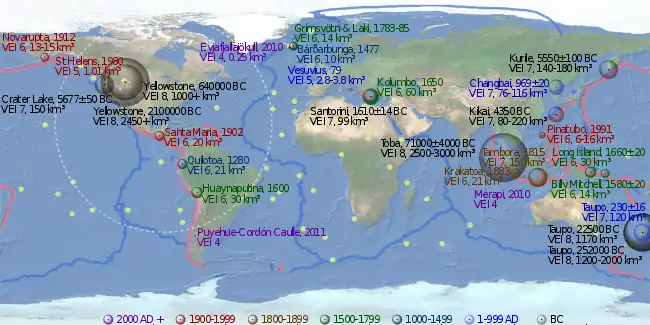

This article is a list of volcanic eruptions of approximately magnitude 6 or more on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) or equivalent sulfur dioxide emission during the Holocene, and Pleistocene eruptions of the Decade Volcanoes (Avachinsky–Koryaksky, Kamchatka; Colima, Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt; Mount Etna, Sicily; Galeras, Andes, Northern Volcanic Zone; Mauna Loa, Hawaii; Mount Merapi, Central Java; Mount Nyiragongo, East African Rift; Mount Rainier, Washington; Sakurajima, Kagoshima Prefecture; Santamaria/ Santiaguito, Central America Volcanic Arc; Santorini, Cyclades; Taal Volcano, Luzon Volcanic Arc; Teide, Canary Islands; Ulawun, New Britain; Mount Unzen, Nagasaki Prefecture; Mount Vesuvius, Naples); Campania, Italy; South Aegean Volcanic Arc; Laguna de Bay, Luzon Volcanic Arc; Mount Pinatubo, Luzon Volcanic Arc; Toba, Sunda Arc; Mount Meager massif, Garibaldi Volcanic Belt; Yellowstone hotspot, Wyoming; and Taupō Volcanic Zone, greater than VEI 4.

The eruptions in the Holocene on the link: Holocene Volcanoes in Kamchatka were not added yet, but they are listed on the Peter L. Ward's supplemental table.[1] Some of the eruptions are not listed on the Global Volcanism Program timetable as well, at least not as VEI 6. The timetables of Global Volcanism Program;[2] Bristlecone pine tree-rings (Pinus longaeva, Pinus aristata, Pinus ponderosa, Pinus edulis, Pseudotsuga menziesii);[3] the 4 ka Yamal Peninsula Siberian larch (Larix sibirica) chronology;[4] the 7 ka Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) chronology from Finnish Lapland;[5][6] GISP2 ice core;[7][8] GRIP ice core;[9] Dye 3 ice core;[9] Bipolar comparison;[10] Antarctic ice core (Bunder and Cole-Dai, 2003);[11] Antarctic ice core (Cole-Dai et al., 1997);[12] Crête ice core, in central Greenland,[13] benthic foraminifera in deep sea sediment cores (Lisiecki, Raymo 2005),[14] do not agree with each other sometimes. The 536–547 AD dust-veil event might be an impact event.[3][15]

Holocene eruptions

The Holocene epoch begins 11,700 years BP,[16] (10 000 14C years ago)

Since 2000 AD

| Name and area | Date | VEI | Products | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai, Tonga | 2022 | 5 | 6.5 km3 (dense-rock equivalent) of tephra | The largest eruption of the 21st century |

| Puyehue-Cordón Caulle, Southern Chile | 2011 | 5 |

1000–2000 AD

| Name and area | Date | VEI | Products | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinatubo, island of Luzon, Philippines | 1991, Jun 15 | 6 | 6 to 16 km3 (1.4 to 3.8 cu mi) of tephra | [2] an estimated 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted[17] |

| Mount St. Helens, Washington state, USA | 1980, May 18 | 5 | 1 to 1.1 km3 (0.2 to 0.3 cu mi) of tephra | |

| Novarupta, Alaska Peninsula | 1912, Jun 6 | 6 | 13 to 15 km3 (3.1 to 3.6 cu mi) of lava[18][19][20] | |

| Santa Maria, Guatemala | 1902, Oct 24 | 6 | 20 km3 (4.8 cu mi) of tephra[21] | |

| Mount Tarawera, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 1886, Jun 10 | 5 | 2 km3 (0.48 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Krakatoa, Indonesia | 1883, August 26–27 | 6 | 21 km3 (5.0 cu mi) of tephra[22] | |

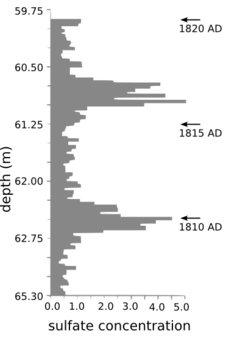

| Mount Tambora, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia | 1815, Apr 10 | 7 | 160–213 km3 (38–51 cu mi) of tephra | an estimated 10–120 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted, produced the "Year Without a Summer"[23] |

| 1808 ice core event | Unknown eruption near equator, magnitude roughly half Tambora | Emission of sulfur dioxide around the amount of the 1815 Tambora eruption (ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland).[24] | ||

| 1808 | Major eruptions in Urzelina, Azores (Urzelina eruption, fissure vent), Klyuchevskaya Sopka, Kamchatka Peninsula,[25] and Taal Volcano, Philippines.[26] | |||

| Note: Thompson Island, northeast of Bouvet Island, South Atlantic Ocean, disappeared in the 19th century, if it ever existed.[27] | ||||

| Grímsvötn, Northeastern Iceland | 1783–1784 | 6 | ||

| Laki | 1783–1784 | 6 | 14 cubic kilometres of lava | an estimated 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted, produced a Volcanic winter, 1783, on the North Hemisphere.[28] |

| Long Island (Papua New Guinea), northeast of New Guinea | 1660 ±20 | 6 | 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Kolumbo, Santorini, Greece | 1650, Sep 27 | 6 | 60 km3 (14.4 cu mi) of tephra[29] | |

| Huaynaputina, Peru | 1600, Feb 19 | 6 | 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[30] | |

| Billy Mitchell, Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea | 1580 ±20 | 6 | 14 km3 (3.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Bárðarbunga, Northeastern Iceland | 1477 | 6 | 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| 1452–53 ice core event, New Hebrides arc, Vanuatu. Location is uncertain, may be Kuwae | 36 to 96 km3 (8.6 to 23.0 cu mi) of tephra | 175–700 million tons of sulfuric acid;[31][32][33] only small pyroclastic flows are found at Kuwae | ||

| Mount Tarawera, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 1310 ± 12 | 5 | 5 km3 (1.2 cu mi) of tephra (Kaharoa eruption)[2] | |

| Quilotoa, Ecuador | 1280(?) | 6 | 21 km3 (5.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Samalas volcano, Rinjani Volcanic Complex, Lombok Island, Indonesia | 1257 | 7 | 40 km3 (dense-rock equivalent) of tephra | 1257 Samalas eruption; Arctic and Antarctic ice cores provide compelling evidence to link the ice core sulfate spike of 1258/1259 A.D. to this volcano.[34][35][36] |

1 to 1000 AD

| Tianchi eruption, Paektu Mountain, border of North Korea and China | 946 AD | 6 | 40 to 98 km3 (9.6 to 23.5 cu mi) of tephra[37] | Also known as Millennium Eruption of Changbaishan |

| Eldgjá eruption, Laki system, Iceland | 934–940 AD | 6 | Estimated 18 km3 (4.3 cu mi) of lava[38] | Estimated 219 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted[39] |

| Ceboruco, Northwest of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | 930 AD ±200 | 6 | 11 km3 (2.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Dakataua, Northern tip of the Willaumez Peninsula, New Britain, Papua New Guinea | 800 AD ±50 | 6? | 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi)? of tephra[2] | |

| Pago, East of Kimbe, New Britain, Papua New Guinea: Witori Caldera | 710 AD ±75 | 6 | 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Churchill, eastern Alaska | 700 AD ±200 | 6 | 20 km3 (4.8 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Rabaul, Rabaul Caldera, New Britain | 540 AD ±100 | 6 | 11 km3 (2.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Ilopango, El Salvador | 431 AD ±2, or 539/540 AD | 7 | 106.5 km3 (25.5 cu mi) of tephra[40][2] | |

| Ksudach, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia | 240 AD ±l00 | 6 | 20 to 26 km3 (4.8 to 6.2 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Hatepe eruption of Taupō Volcano, New Zealand | 230 AD ±16 | 7 | 120 km3 (29 cu mi) of tephra[41] | |

| Mount Vesuvius, Italy | 79 AD Oct 24 (?) | 5? | 2.8 to 3.8 km3 (0.7 to 0.9 cu mi) of tephra[2][42][43] | Pompeii eruption |

| Mount Churchill, eastern Alaska | 60 AD ±200 | 6 | 25 km3 (6.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Ambrym, Vanuatu | 50 AD ±100 | 6 | 60 to 80 km3 (14.4 to 19.2 cu mi) of tephra[2] |

Before the Common Era (BC/BCE)

| Name and area | Date | VEI | Products | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okmok, Okmok Caldera, Aleutian Islands | 44 BC[44] | 6 | 40 to 60 km3 (9.6 to 14.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Apoyeque, Nicaragua | 50 BC ±100 | 6 | 18 km3 (4.3 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Raoul Island, Kermadec Islands, New Zealand | 250 BC ±75 | 6 | more than 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Meager massif, Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, Canada | 400 BC ±50 | 5 | ||

| Mount Tongariro, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 550 BC ±200 | 5 | 1.2 km3 (0.29 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Pinatubo, island of Luzon, Philippines | 1050 BC ±500 | 6 | 10 to 16 km3 (2.4 to 3.8 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Avachinsky, Kamchatka | 1350 BC (?) | 5 | more than 1.2 km3 (0.29 cu mi) of tephra | tephra layer IIAV3[2] |

| Pago, east of Kimbe, New Britain, Papua New Guinea: Witori Caldera | 1370 BC ±100 | 6 | 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Taupō, New Zealand | 1460 BC ±40 | 6 | 17 km3 (4.1 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Avachinsky, Kamchatka | 1500 BC (?) | 5 | more than 3.6 km3 (0.86 cu mi) of tephra | tephra layer AV1[2] |

| Santorini (Thera), Greece, Youngest Caldera: Minoan eruption | 1610 BC ±14 years | 7 | 123 km3 (30 cu mi) of tephra[45] | Ended the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri and the Minoan age on Crete |

| Mount Aniakchak, Alaska Peninsula | 1645 BC ±10 | 6 | more than 50 km3 (12 cu mi) of tephra[2] | Severe global cooling[46] |

| Veniaminof, Alaska Peninsula | 1750 BC (?) | 6 | more than 50 km3 (12 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount St. Helens, Washington, USA | 1860 BC (?) | 6 | 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Hudson, Cerro, Southern Chile | 1890 BC (?) | 6 | more than 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Black Peak, Alaska Peninsula | 1900 BC ±150 | 6 | 10 to 50 km3 (2.4 to 12.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Long Island (Papua New Guinea), Northeast of New Guinea | 2040 BC ± 100 | 6 | more than 11 km3 (2.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Vesuvius, Italy | 2420 BC ±40 | 5? | 3.9 km3 (0.94 cu mi) of tephra | Avellino eruption[2][42][43][47] |

| Avachinsky, Kamchatka | 3200 BC ±150 | 5 | more than 1.1 km3 (0.26 cu mi) of tephra | tephra layer IAv20 AV3[2] |

| Pinatubo, island of Luzon, Philippines | 3550 BC (?) | 6 | 10 to 16 km3 (2.4 to 3.8 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Talisay (Taal) caldera (size: 15 x 20 km), island of Luzon, Philippines | 3580 BC ±200 | 7 | 150 km3 (36 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Haroharo Caldera, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 3580 BC ±50 | 5 | 2.8 km3 (0.67 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Pago, New Britain | 4000 BC ± 200 | 6? | 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi)? of tephra[2] | |

| Masaya Volcano, Nicaragua | 4050 BC (?) | 6 | more than 13 km3 (3.1 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Avachinsky, Kamchatka | 4340 BC ±75 | 5 | more than 1.3 km3 (0.31 cu mi) of tephra | tephra layer IAv12 AV4[2] |

| Macauley Island, Kermadec Islands, New Zealand | 4360 BC ±200 | 6 | 100 km3 (24 cu mi)? of tephra[2][48] | |

| Mount Hudson, Cerro, Southern Chile | 4750 BC (?) | 6 | 18 km3 (4.3 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Aniakchak, Alaska Peninsula | 5250 BC ±1000 | 6 | 10 to 50 km3 (2.4 to 12.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Kikai Caldera (size: 19 km), Ryukyu Islands, Japan: Akahoya eruption | 5350 BC (?) | 7 | 80 to 220 km3 (19.2 to 52.8 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mashu, Hokkaido, Japan | 5550 BC ±100 | 6 | 19 km3 (4.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Tao-Rusyr Caldera, Kuril Islands | 5550 BC ±75 | 6 | 30 to 36 cubic kilometers (7.2 to 8.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mayor Island / Tūhua, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 5060 BC ±200 | 5 | 1.6 km3 (0.38 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Crater Lake (Mount Mazama), Oregon, USA | 5677 BC ±150 | 7 | 150 km3 (36 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Khangar, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia | 5700 BC ± 16 | 6 | 14 to 16 km3 (3.4 to 3.8 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Crater Lake (Mount Mazama), Oregon, USA | 5900 BC ± 50 | 6 | 8 to 28 km3 (1.9 to 6.7 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Avachinsky, Kamchatka | 5980 BC ±100 | 5 | more than 8 to 10 km3 (1.9 to 2.4 cu mi) of tephra | tephra layer IAv1[2] |

| Menengai, East African Rift, Kenya | 6050 BC (?) | 6 | 70 km3 (17 cu mi)? of tephra[2] | |

| Haroharo Caldera, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 6060 BC ±50 | 5 | 1.2 km3 (0.29 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Sakurajima, island of Kyūshū, Japan: Aira Caldera | 6200 BC ±1000 | 6 | 12 km3 (2.9 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Kurile Caldera (size: 8 x 14 km), Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia | 6440 BC ± 25 years | 7 | 140 to 170 km3 (33.6 to 40.8 cu mi) of tephra | Ilinsky eruption[2] |

| Karymsky, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia | 6600 BC (?) | 6 | 50 to 350 km3 (12.0 to 84.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Vesuvius, Italy | 6940 BC ±100 | 5? | 2.75 to 2.85 km3 (0.7 to 0.7 cu mi) of tephra | Mercato eruption[2][42][43] |

| Fisher Caldera, Unimak Island, Aleutian Islands | 7420 BC ±200 | 6 | more than 50 km3 (12 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Pinatubo, island of Luzon, Philippines | 7460 BC ±150 | 6–7?[2] | ||

| Lvinaya Past, Kuril Islands | 7480 BC ±50 | 6 | 7 to 8 km3 (1.7 to 1.9 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Rotomā Caldera, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 7560 BC ±18 | 5 | more than 5.6 km3 (1.3 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Taupō Volcano, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 8130 BC ±200 | 5 | 4.7 km3 (1.1 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Grímsvötn, Northeastern Iceland | 8230 BC ±50 | 6 | more than 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Ulleung, Korea | 8750 BC (?) | 6 | more than 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Tongariro, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 9450 BC (?) | 5 | 1.7 km3 (0.41 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Taupō Volcano, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 9460 BC ±200 | 5 | 1.4 km3 (0.34 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Mount Tongariro, Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand | 9650 BC (?) | 5 | 1.6 km3 (0.38 cu mi) of tephra[2] | |

| Nevado de Toluca, State of Mexico, Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | 10.5 ka | 6 | 14 km3 (3.4 cu mi) of tephra | Upper Toluca Pumice[2][49] |

| GISP2 ice core event[1] | 11.258 ka |

Pleistocene eruptions

2.588 ± 0.005 million years BP, the Quaternary period and Pleistocene epoch begin.[50]

| Name and area | Date | VEI | Products | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GISP2 ice core event[1] | 12.657 ka | ||||

| Eifel hotspot, Laacher See, Vulkan Eifel, Germany | 12.900 ka | 6 | 6 km3 (1.4 cu mi) of tephra.[51][52][53][54] | ||

| Mount Vesuvius, Italy | 16 ka | 5 | Green Pumice[42][43] | ||

| Mount Vesuvius, Italy | 18.3 ka | 6 | Basal Pumice[42][43] | ||

| Santorini (Thera), Greece: Cape Riva Caldera | about 21 ka[2] | ||||

| Aira Caldera, south of the island of Kyūshū, Japan | about 22 ka | 7 | more than 400 km3 (96.0 cu mi) of tephra.[55] | ||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Oruanui eruption, Taupō Volcano, New Zealand | around 25.6 ka [56] | 8 | Approximately 1,170 km3 (280.7 cu mi) of tephra[57][58][59][60] | ||

| Laguna Caldera (size: 10 x 20 km), South-East of Manila, island of Luzon | 27–29 ka[2] | ||||

| Alban Hills, Rome, Italy | 36 ka | 4 | Peperino Ignimbrite of Albano Maar | Sedimentation and mobility of PDCs: a reappraisal of ignimbrites’ aspect ratio[61] | |

| Campi Flegrei, Naples, Italy | 39.280 ka ± 0.11 | [62] 200 cubic kilometres of lava | Campanian Tuff [1] | ||

| Galeras, Andes, Northern Volcanic Zone, Colombian department of Nariño | 40 ka | 2 km3 (0.5 cu mi) of tephra | |||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Rotoiti Ignimbrite, North Island, New Zealand | about 50 ka | 7 | about 240 km3 (57.6 cu mi) of tephra.[63] | ||

| Santorini (Thera), Greece: Skaros Caldera | about 70 ka[2] | ||||

| Lake Toba (size: 100 x 30 km), Sumatra, Indonesia | 73.7 ka ± 0.3[64] | 2,500 to 3,000 km3 (599.8 to 719.7 cu mi) of tephra[65] | estimated 150 to 1,000 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted (Youngest Toba Tuff).[66] | ||

| Aso Caldera, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan | 90 ka | 8 | 930 to 1,860 km3 (223.1 to 446.2 cu mi) of tephra[67] | The largest known eruption in Japan | |

| Yellowstone hotspot: Yellowstone Caldera | between 70 and 150 ka | 1,000 km3 (239.9 cu mi) intracaldera rhyolitic lava flows.[2] | |||

| Galeras, Andes, Northern Volcanic Zone, Colombian department of Nariño | 150 ka | 2 km3 (0.5 cu mi) of tephra | |||

| Kos-Nisyros Caldera, Greece | 161 ka | 110 km3 (26 cu mi) | Kos Plateau Tuff.[1] | ||

| Taal Caldera, island of Luzon, Philippines | between 500 and 100 ka | 25–30 km caldera formed by four explosive eruptions | |||

| Santorini (Thera), Greece: Southern Caldera | about 180 ka[2] | ||||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Rotorua Caldera (size: 22 km wide), New Zealand | 220 ka | more than 340 km3 (81.6 cu mi) of tephra.[1] | |||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Maroa Caldera (size: 16 x 25 km), New Zealand | 230 ka | 140 km3 (33.6 cu mi) of tephra.[1] | |||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Reporoa Caldera (size: 10 x 15 km), New Zealand | 230 ka | 7 | around 100 km3 (24.0 cu mi) of tephra[2] | ||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Whakamaru Caldera (size: 30 x 40 km), North Island, New Zealand | around 254 ka | 8 | 1,200 to 2,000 km3 (288 to 480 cu mi) of tephra | Whakamaru Ignimbrite/Mount Curl Tephra[68][69] | |

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Matahina Ignimbrite, Haroharo Caldera, North Island, New Zealand | 280 ka | 7 | about 120 km3 (28.8 cu mi) of tephra.[70] | ||

| Alban Hills, Rome, Italy | 365–351 ka | 6 | Villa Senni Ignimbrite >50km3 | Volcanoes of the World: Third Edition [71] | |

| Sabatini volcanic complex, Sabatini, Italy | 374 ka | 7 | more than 200 km3 (48 cu mi) | Morphi tephra.[1] | |

| Roccamonfina Caldera (size: 65 x 55 km), Roccamonfina, Italy | 385 ka | 100 to 125 km3 (24.0 to 30.0 cu mi) of tephra.[1] | |||

| Alban Hills, Rome, Italy | 407–398 ka | 6 | Pozzolane Nere Ignimbrite [71] | ||

| Alban Hills, Rome, Italy | 456–439 ka | 7 | Pozzolane Rosse Tephritic Ignimbrite >50km3 | Sedimentation and mobility of PDCs: a reappraisal of ignimbrites’ aspect ratio[61] | |

| Maipo (volcano), Andes, Southern Volcanic Zone, Chile | 450–500 ka | 7 | Diamante Caldera | ||

| Galeras, Andes, Northern Volcanic Zone, Colombian department of Nariño | 560 ka | 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of tephra | |||

| Lake Toba, Sumatra, Indonesia | 501 ka ±5 | Middle Toba Tuff[65] | |||

| Yellowstone hotspot: Yellowstone Caldera (size: 45 x 85 km) | 640 ka | 8 | more than 1,000 km3 (240 cu mi) of tephra | Lava Creek Tuff[2] | |

| Lake Toba, Sumatra, Indonesia | 840 ka ±30 | Oldest Toba Tuff[65] | |||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Mangakino Caldera, North Island, New Zealand | 0.97 Ma | more than 300 km3 (72.0 cu mi) | Rocky Hill Ignimbrite[1] | ||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Mangakino Caldera, North Island, New Zealand | 1.01 Ma | more than 300 km3 (72.0 cu mi) | Unit E[1] | ||

| Lake Toba, Sumatra, Indonesia | 1.2 ±0.16 Ma | Haranggoal Dacite Tuff[65] | |||

| Taupō Volcanic Zone, Mangakino Caldera, North Island, New Zealand | 1.23 Ma | more than 300 km3 (72.0 cu mi) | Ongatit Ignimbrite[1][72] | ||

| Yellowstone hotspot: Henry's Fork Caldera (size: 16 km wide) | 1.3 Ma | 7 | 280 km3 (67.2 cu mi) | Mesa Falls Tuff.[2] | |

| Yellowstone hotspot: Island Park Caldera (size: 100 x 50 km) | 2.1 Ma | 8 | 2,450 km3 (588 cu mi) | Huckleberry Ridge Tuff.[1][2] | |

| Cerro Galán Caldera, Argentina (size: 35 x 20 km) | 2.2 Ma | 8 | 1,000 km3 (240 cu mi) of dacitic magma.[73] |

Notes

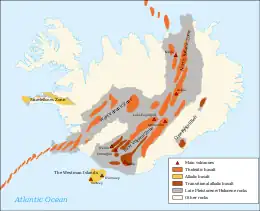

- Iceland has four volcanic zones: Reykjanes (Mid-Atlantic Ridge),[74] West and North Volcanic Zones (RVZ, WVZ, NVZ) and the East Volcanic Zone (EVZ). The Mid-Iceland Belt (MIB) connects them across central Iceland. There are two intraplate belts too (Öræfajökull (ÖVB) and Snæfellsnes (SVB)).

- Iceland's East Volcanic Zone: the central volcanoes of Vonarskard and Hágöngur belong to the same volcanic system; this also applies to Bárðarbunga and Hamarinn, and Grímsvötn and Þórðarhyrna.[75][76][77]

- Laki is part of a volcanic system, centering on the Grímsvötn volcano (Long NE-SW-trending fissure systems, including Laki, extend from the central volcano).[2]

- The Eldgjá canyon and the Katla volcano form another volcanic system. Although the Eldgjá canyon and the Laki fissure are very near from each other, lava from the Katla and the Hekla volcanic systems result in transitional alkalic basalts and lava from the central volcanoes result in tholeiitic basalts.

- The central volcano of Bárðarbunga, the Veidivötn and Trollagigar fissures form one volcanic system, which extend about 100 km SW to near Torfajökull volcano and 50 km NE to near Askja volcano, respectively. The subglacial Loki-Fögrufjöll volcanic system located SW of Bárðarbunga volcano is also part of the Bárðarbunga volcanic system and contains two subglacial ridges extending from the largely subglacial Hamarinn central volcano (15 km southwest of Bárðarbunga); the Loki ridge trends to the NE and the Fögrufjöll ridge to the SW.[2]

- Iceland's East Volcanic Zone: the central volcanoes of Vonarskard and Hágöngur belong to the same volcanic system; this also applies to Bárðarbunga and Hamarinn, and Grímsvötn and Þórðarhyrna.[75][76][77]

- New Zealand, North Island, Taupō Volcanic Zone:

- The following Volcanic Centers belong to the Taupō Volcanic Zone: Rotorua, Ōkataina, Maroa, Taupō, Tongariro and Mangakino.[78] It includes Mangakino volcano, Reporoa Caldera, Mount Tarawera, Mount Ruapehu, Mount Tongariro and Whakaari / White Island. The Taupō Volcanic Zone forms a southern portion of the active Lau-Havre-Taupō back-arc basin, which lies behind the Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone (Hikurangi Trough – Kermadec Trench – Tonga Trench).[79] Some lakes in the area: Taupo, Rotorua, Rotomahana, and Rerewhakaaitu. Lake Ōkataina, Lake Tarawera, Lake Rotokakahi (Green Lake), Lake Tikitapu (Blue Lake), Lake Okareka, and Lake Rotoiti lie within the Ōkataina Caldera.

- Taupō Volcanic Zone, the Mangakino Volcanic Center is the westernmost and oldest rhyolitic caldera volcano in the Taupō Volcanic Zone. Mangakino is a town too.[80]

- Taupō Volcanic Zone, Maroa Volcanic Center. The Maroa Caldera formed in the Northeast corner of the Whakamaru Caldera. The Whakamaru Caldera partially overlaps with the Taupō Caldera on the South. The Orakeikorako, Ngatamariki, Rotokaua, and Wairakei hydrothermal areas are located within or adjacent to the Whakamaru caldera. Whakamaru is a town too.[2]

- The oldest volcanic zone in the North Island is the Northland Region, then the Coromandel Volcanic Zone (CVZ), then the Mangakino caldera complex and the Kapenga Caldera and then the rest of the Taupō Volcanic Zone (TVZ).

- Santorini, South Aegean Volcanic Arc. The southern Aegean is one of the most rapidly deforming regions of the Himalayan-Alpine mountain belt (Alpide belt).[81]

- The twin volcanoes of Nindirí and Masaya lie within the massive Pleistocene Las Sierras pyroclastic shield volcano.[2]

- There are two peaks in the Colima volcano complex: Nevado de Colima (4,330 m), which is older and inactive, lies 5 km north of the younger and very active 3,860 m Volcán de Colima (also called Volcán de Fuego de Colima).

- The largely submarine Kuwae Caldera cuts the flank of the Late Pleistocene or Holocene Tavani Ruru volcano, the submarine volcano Karua lies near the northern rim of Kuwae Caldera.[2]

- Bismarck volcanic arc, the Rabaul Caldera includes the sub-vent of Tavurvur and the sub-vent of Vulcan.

- Bismarck volcanic arc, Pago volcano, New Britain, Papua New Guinea, is a young post-caldera cone within the Witori Caldera. The Buru Caldera cuts the SW flank of the Witori volcano.[2]

- Sakurajima, Kyūshū, Japan, is a volcano of the Aira Caldera.

- The Mount Unzen volcanic complex, East of Nagasaki, Japan, comprises three large stratovolcanoes with complex structures, Kinugasa on the North, Fugen-dake at the East-center, and Kusenbu on the South.

Nomenclature

Each state/ country seem to have a slightly different approach, but there is an order:

- Craton, and then Province as sections or regions of a craton.

- First: volcanic arc, volcanic belt and volcanic zone.

- Second: volcanic area, caldera cluster and caldera complex.

- Third: volcanic field, volcanic system and volcanic center.

- A volcanic field is a localized area of the Earth's crust that is prone to localized volcanic activity.

- A volcanic group (aka a volcanic complex) is a collection of related volcanoes or volcanic landforms.

- Neutral: volcanic cluster and volcanic locus.

In the Basin and Range Province the volcanic fields are nested. The McDermit volcanic field, is also named Orevada rift volcanic field. The Latir-Questa volcanic locus and the Taos Plateau volcanic field seem to be in a similar area. The Southwest Nevada volcanic field, the Crater Flat-Lunar Crater volcanic zone, the Central Nevada volcanic field, the Indian Peak volcanic field and the Marysvale volcanic field seem to have no transition between each other; the Ocate volcanic field is also known as the Mora volcanic field; and the Red Hill volcanic field is also known as Quemado volcanic field.

References

- "Supplementary Table to P.L. Ward, Thin Solid Films (2009) Major volcanic eruptions and provinces" (PDF). Teton Tectonics. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/largeeruptions.cfm Large Holocene Eruptions Archived February 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Salzer, Matthew W.; Malcolm K. Hughes (2007). "Bristlecone pine tree rings and volcanic eruptions over the last 5000 yr" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 67 (1): 57–68. Bibcode:2007QuRes..67...57S. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.07.004. S2CID 14654597. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- Hantemirov, Rashit M.; Shiyatov, Stepan G. (September 2002). "A continuous multimillennial ring-width chronology in Yamal, northwestern Siberia". The Holocene. 12 (6): 717–726. Bibcode:2002Holoc..12..717H. doi:10.1191/0959683602hl585rp. S2CID 129192118.

- Eronen, Matti; Zetterberg, Pentti; Briffa, Keith R.; Lindholm, Markus; Meriläinen, Jouko; Timonen, Mauri (September 2002). "The supra-long Scots pine tree-ring record for Finnish Lapland: Part 1, chronology construction and initial inferences". The Holocene. 12 (6): 673–680. Bibcode:2002Holoc..12..673E. doi:10.1191/0959683602hl580rp. S2CID 54806912.

- Helama, Samuli; Lindholm, Markus; Timonen, Mauri; Meriläinen, Jouko; Eronen, Matti (September 2002). "The supra-long Scots pine tree-ring record for Finnish Lapland: Part 2, interannual to centennial variability in summer temperatures for 7500 years". The Holocene. 12 (6): 681–687. Bibcode:2002Holoc..12..681H. doi:10.1191/0959683602hl581rp. S2CID 129520871.

- Zielinski, G. A.; Mayewski, P. A.; Meeker, L. D.; Whitlow, S.; Twickler, M. S.; Morrison, M.; Meese, D. A.; Gow, A. J.; Alley, R. B. (13 May 1994). "Record of Volcanism Since 7000 B.C. from the GISP2 Greenland Ice Core and Implications for the Volcano-Climate System". Science. 264 (5161): 948–952. Bibcode:1994Sci...264..948Z. doi:10.1126/science.264.5161.948. PMID 17830082. S2CID 21695750.

- Zielinski, Gregory A. (1995). "Stratospheric loading and optical depth estimates of explosive volcanism over the last 2100 years derived from the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 ice core". Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (D10): 20937. Bibcode:1995JGR...10020937Z. doi:10.1029/95JD01751.

- Clausen, Henrik B.; Hammer, Claus U.; Hvidberg, Christine S.; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Kipfstuhl, Josef; Legrand, Michel (30 November 1997). "A comparison of the volcanic records over the past 4000 years from the Greenland Ice Core Project and Dye 3 Greenland ice cores". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 102 (C12): 26707–26723. Bibcode:1997JGR...10226707C. doi:10.1029/97JC00587.

- Langway, C. C.; Osada, K.; Clausen, H. B.; Hammer, C. U.; Shoji, H. (1995). "A 10-century comparison of prominent bipolar volcanic events in ice cores". Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (D8): 16241. Bibcode:1995JGR...10016241L. doi:10.1029/95JD01175.

- Budner, Drew; Cole-Dai, Jihong (2003). "The number and magnitude of explosive volcanic eruptions between 904 and 1865 A.D.: Quantitative evidence from a new South Pole ice core" (PDF). In Robock, A.; Oppenheimer, C. (eds.). Volcanism and the Earth's Atmosphere. Geophysical Monograph Series. Vol. 139. American Geophysical Union. pp. 165–176. Bibcode:2003GMS...139..165B. doi:10.1029/139GM10. ISBN 978-0-87590-998-1.

The number and magnitude of large explosive volcanic eruptions between 904 and 1865 A.D.: Quantitative evidence from a new South Pole ice core

- Cole-Dai, Jihong; Mosley-Thompson, Ellen; Thompson, Lonnie G. (27 July 1997). "Annually resolved southern hemisphere volcanic history from two Antarctic ice cores". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 102 (D14): 16761–16771. Bibcode:1997JGR...10216761C. doi:10.1029/97JD01394.

- Crowley, Thomas J.; Criste, Tamara A.; Smith, Neil R. (5 February 1993). "Reassessment of Crete (Greenland) ice core acidity/volcanism link to climate change". Geophysical Research Letters. 20 (3): 209–212. Bibcode:1993GeoRL..20..209C. doi:10.1029/93GL00207.

- Lisiecki, L. E.; Raymo, M. E. (January 2005). "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records" (PDF). Paleoceanography. 20 (1): PA1003. Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.1003L. doi:10.1029/2004PA001071. hdl:2027.42/149224. S2CID 12788441.

Lisiecki, L. E.; Raymo, M. E. (May 2005). "Correction to "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records"". Paleoceanography. 20 (2): PA2007. Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.2007L. doi:10.1029/2005PA001164. S2CID 128995657.

data: Lisiecki, Lorraine E; Raymo, Maureen E (2005). "Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of globally distributed benthic stable oxygen isotope records". Pangaea: 3 datasets. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.704257. Supplement to Lisiecki, Lorraine E.; Raymo, Maureen E. (2005). "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records". Paleoceanography. 20 (1). Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.1003L. doi:10.1029/2004Pa001071. S2CID 12788441. - Baillie, M.G.L. (1994). "Dendrochronology raises questions about the nature of the AD 536 dust-veil event". The Holocene. 4 (2): 212–7. Bibcode:1994Holoc...4..212B. doi:10.1177/095968369400400211. S2CID 140595125.

- "International Stratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Robock, A.; C.M. Ammann; L. Oman, D. Shindell; S. Levis; G. Stenchikov (2009). "Did the Toba volcanic eruption of ~74k BP produce widespread glaciation?". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (D10): D10107. Bibcode:2009JGRD..11410107R. doi:10.1029/2008JD011652.

- Brantley, Steven R. (1999-01-04). Volcanoes of the United States. United States Geological Survey. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-16-045054-9. OCLC 156941033. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- Judy Fierstein; Wes Hildreth; James W. Hendley II; Peter H. Stauffer (1998). "Can Another Great Volcanic Eruption Happen in Alaska?". United States Geological Survey. Fact Sheet 075-98. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- Fierstein, Judy; Wes Hildreth (2004-12-11). "The plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Katmai National Park, Alaska". Bulletin of Volcanology. Springer. 54 (8): 646. Bibcode:1992BVol...54..646F. doi:10.1007/BF00430778. S2CID 86862398.

- "Santa Maria". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Hopkinson, Deborah (January 2004). "The Volcano That Shook the world: Krakatoa 1883". Scholastic.com. New York: Storyworks. 11 (4): 8.

- Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). "Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815". Progress in Physical Geography. 27 (2): 230–259. doi:10.1191/0309133303pp379ra. S2CID 131663534.

- Dai, Jihong; Mosley-Thompson, Ellen; Thompson, Lonnie G. (1991). "Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 96 (D9): 17, 361–17, 366. Bibcode:1991JGR....9617361D. doi:10.1029/91jd01634.

- "Документ без названия". Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- "Saderra Maso: Historical Taal". www.iml.rwth-aachen.de.

- Baker, P. E. (1967). "Historical and geological notes on Bouvetoya" (PDF). British Antarctic Survey Bulletin. 13: 71–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

Abstract: it is suggested that "Thompson Island",... may have disappeared as a result of a volcanic eruption during the nineteenth century.

- BBC Timewatch: "Killer Cloud", broadcast 19 January 2007

- Haraldur Sigurdsson; S. Carey; C. Mandeville (1990). Assessment of mass, dynamics and environmental effects of the Minoan eruption of the Santorini volcano. Thera and the Aegean World III: Proceedings of the Third Thera Conference. Vol. II. pp. 100–12.

- "Huaynaputina". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Nemeth, Karoly; Shane J. Cronin; James D.L. White (2007). "Kuwae caldera and climate confusion". The Open Geology Journal. 1 (5): 7–11. Bibcode:2007OGJ.....1....7N. doi:10.2174/1874262900701010007.

- Gao, Chaochao; Robock, A.; Self, S.; Witter, J. B.; Steffenson, J. P.; Clausen, H. B.; Siggaard-Andersen, M.-L.; Johnsen, S.; Mayewski, P. A.; Ammann, C. (27 June 2006). "The 1452 or 1453 A.D. Kuwae eruption signal derived from multiple ice core records: Greatest volcanic sulfate event of the past 700 years". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (D12): D12107. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11112107G. doi:10.1029/2005JD006710. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Witter, J.B.; Self S. (January 2007). "The Kuwae (Vanuatu) eruption of AD 1452: potential magnitude and volatile release". Bulletin of Volcanology. 69 (3): 301–318. Bibcode:2007BVol...69..301W. doi:10.1007/s00445-006-0075-4. S2CID 129403009.

- Lavigne, Franck (4 September 2013). "Source of the great A.D. 1257 mystery eruption unveiled, Samalas volcano, Rinjani Volcanic Complex, Indonesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (42): 16742–16747. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11016742L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307520110. PMC 3801080. PMID 24082132.

- "Mystery 13th Century eruption traced to Lombok, Indonesia". BBC News. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Oppenheimer, Clive (19 March 2003). "Ice core and palaeoclimatic evidence for the timing and nature of the great mid-13th century volcanic eruption". International Journal of Climatology. Royal Meteorological Society. 23 (4): 417–426. Bibcode:2003IJCli..23..417O. doi:10.1002/joc.891. S2CID 129835887.

- Yang, Qingyuan; Jenkins, Susanna F.; Lerner, Geoffrey A.; Li, Weiran; Suzuki, Takehiko; McLean, Danielle; Derkachev, A. N.; Utkin, I. V.; Wei, Haiquan; Xu, Jiandong; Pan, Bo (2021-10-23). "The Millennium Eruption of Changbaishan Tianchi Volcano is VEI 6, not 7". Bulletin of Volcanology. 83 (11): 74. Bibcode:2021BVol...83...74Y. doi:10.1007/s00445-021-01487-8. ISSN 1432-0819. S2CID 239461051.

- "Katla: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- "Laki and Eldgjá—two good reasons to live in Hawai'". USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- Dull, Robert A.; Southon, John R.; Kutterolf, Steffen; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Freundt, Armin; Wahl, David B.; Sheets, Payson; Amaroli, Paul; Hernandez, Walter; Wiemann, Michael C.; Oppenheimer, Clive (October 2019). "Radiocarbon and geologic evidence reveal Ilopango volcano as source of the colossal 'mystery' eruption of 539/40 CE" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 222: 105855. Bibcode:2019QSRv..22205855D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.07.037. S2CID 202190161.

- "Taupo – Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- "Summary of the eruptive history of Mt. Vesuvius". Osservatorio Vesuviano, Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology. Archived from the original on December 3, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "Somma-Vesuvius". Department of Physics, University of Rome. Archived from the original on 2011-04-12. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- McConnell, Joseph R.; Sigl, Michael; Plunkett, Gill; Burke, Andrea; Kim, Woon Mi; Raible, Christoph C.; Wilson, Andrew I.; Manning, Joseph G.; Ludlow, Francis; Chellman, Nathan J.; Innes, Helen M.; Yang, Zhen; Larsen, Jessica F.; Schaefer, Janet R.; Kipfstuhl, Sepp; Mojtabavi, Seyedhamidreza; Wilhelms, Frank; Opel, Thomas; Meyer, Hanno; Steffensen, Jørgen Peder (7 July 2020). "Extreme climate after massive eruption of Alaska's Okmok volcano in 43 BCE and effects on the late Roman Republic and Ptolemaic Kingdom". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (27): 15443–15449. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11715443M. doi:10.1073/pnas.2002722117. PMC 7354934. PMID 32571905.

- Johnston, E. N.; Sparks, R. S. J.; Phillips, J. C.; Carey, S. (July 2014). "Revised estimates for the volume of the Late Bronze Age Minoan eruption, Santorini, Greece". Journal of the Geological Society. 171 (4): 583–590. Bibcode:2014JGSoc.171..583J. doi:10.1144/jgs2013-113. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 129937513.

- McAneney, Jonny; Baillie, Mike (February 2019). "Absolute tree-ring dates for the Late Bronze Age eruptions of Aniakchak and Thera in light of a proposed revision of ice-core chronologies". Antiquity. 93 (367): 99–112. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.165. S2CID 166461015.

- "An ancient Bronze Age village (3500 bp) destroyed by the pumice eruption in Avellino (Nola-Campania)". Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Latter, J. H.|| Lloyd, E. F.|| Smith, I. E. M.|| Nathan, S. (1992). Volcanic hazards in the Kermadec Islands and at submarine volcanoes between southern Tonga and New Zealand Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Volcanic hazards information series 4. Wellington, New Zealand. Ministry of Civil Defence. 44 p.

- Arce, J. L.; Macías, J. L.; Vázquez-Selem, L. (1 February 2003). "The 10.5 ka Plinian eruption of Nevado de Toluca volcano, Mexico: Stratigraphy and hazard implications". GSA Bulletin. 115 (2): 230–248. Bibcode:2003GSAB..115..230A. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2003)115<0230:TKPEON>2.0.CO;2.

- Lin, Jiamei; Svensson, Anders; Hvidberg, Christine S.; Lohmann, Johannes; Kristiansen, Steffen; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Steffensen, Jørgen Peder; Rasmussen, Sune Olander; Cook, Eliza; Kjær, Helle Astrid; Vinther, Bo M.; Fischer, Hubertus; Stocker, Thomas; Sigl, Michael; Bigler, Matthias; Severi, Mirko; Traversi, Rita; Mulvaney, Robert (2022). "Magnitude, frequency and climate forcing of global volcanism during the last glacial period as seen in Greenland and Antarctic ice cores (60–9 ka)". Climate of the Past. 18 (3): 485–506. Bibcode:2022CliPa..18..485L. doi:10.5194/cp-18-485-2022. S2CID 247480436.

- van den Bogaard, P (1995). "40Ar/(39Ar) ages of sanidine phenocrysts from Laacher See Tephra (12,900 yr BP): Chronostratigraphic and petrological significance". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 133 (1–2): 163–174. Bibcode:1995E&PSL.133..163V. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(95)00066-L.

- P de Klerk; W Janke; P Kühn; M Theuerkauf (December 2008). "Environmental impact of the Laacher See eruption at a large distance from the volcano: Integrated palaeoecological studies from Vorpommern (NE Germany)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 270 (1–2): 196–214. Bibcode:2008PPP...270..196D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.09.013.

- Baales, Michael; Jöris, Olaf; Street, Martin; Bittmann, Felix; Weninger, Bernhard; Wiethold, Julian (November 2002). "Impact of the Late Glacial Eruption of the Laacher See Volcano, Central Rhineland, Germany". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 273–288. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58..273B. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2379. S2CID 53973827.

- Forscher warnen vor Vulkan-Gefahr in der Eifel. Spiegel Online, 13. Februar 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2008

- Aramaki, Shigeo (1984). "Formation of the Aira Caldera, Southern Kyushu, ~22,000 Years Ago". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B10): 8485–8501. Bibcode:1984JGR....89.8485A. doi:10.1029/JB089iB10p08485.

- Dunbar, Nelia W

- Wilson, Colin J. N. (2001). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: an introduction and overview". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 112 (1–4): 133–174. Bibcode:2001JVGR..112..133W. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00239-6.

- Manville, Vern & Wilson, Colin J. N. (2004). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: a review of the roles of volcanism and climate in the post-eruptive sedimentary response". New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 47 (3): 525–547. doi:10.1080/00288306.2004.9515074.

- Wilson CJ, Blake S, Charlier BL, Sutton AN (2006). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui Eruption, Taupo Volcano, New Zealand: Development, Characteristics and Evacuation of a Large Rhyolitic Magma Body". Journal of Petrology. 47 (1): 35–69. Bibcode:2005JPet...47...35W. doi:10.1093/petrology/egi066.

- Richard Smith, David J. Lowe and Ian Wright. 'Volcanoes – Lake Taupo', Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 16-Apr-2007

- Giordano, Guido; Doronzo, Domenico M. (30 June 2017). "Sedimentation and mobility of PDCs: a reappraisal of ignimbrites' aspect ratio". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 4444. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.4444G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04880-6. PMC 5493644. PMID 28667271.

- De Vivo, B.; Rolandi, G.; Gans, P. B.; Calvert, A.; Bohrson, W. A.; Spera, F. J.; Belkin, H. E. (November 2001). "New constraints on the pyroclastic eruptive history of the Campanian volcanic Plain (Italy)". Mineralogy and Petrology. Springer Wien. 73 (1–3): 47–65. Bibcode:2001MinPe..73...47D. doi:10.1007/s007100170010. S2CID 129762185.

- Froggatt, P. C. & Lowe, D. J. (1990). "A review of late Quaternary silicic and some other tephra formations from New Zealand: their stratigraphy, nomenclature, distribution, volume, and age". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 33: 89–109. doi:10.1080/00288306.1990.10427576.

- Mark, Darren F.; Renne, Paul R.; Dymock, Ross C.; Smith, Victoria C.; Simon, Justin I.; Morgan, Leah E.; Staff, Richard A.; Ellis, Ben S.; Pearce, Nicholas J. G. (2017-04-01). "High-precision 40Ar/39Ar dating of pleistocene tuffs and temporal anchoring of the Matuyama-Brunhes boundary". Quaternary Geochronology. 39: 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2017.01.002. ISSN 1871-1014. S2CID 13742673.

- Chesner, C.A.; Westgate, J.A.; Rose, W.I.; Drake, R.; Deino, A. (March 1991). "Eruptive History of Earth's Largest Quaternary caldera (Toba, Indonesia) Clarified" (PDF). Geology. 19 (3): 200–203. Bibcode:1991Geo....19..200C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0200:EHOESL>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Crick, Laura; Burke, Andrea; Hutchison, William; Kohno, Mika; Moore, Kathryn A.; Savarino, Joel; Doyle, Emily A.; Mahony, Sue; Kipfstuhl, Sepp; Rae, James W. B.; Steele, Robert C. J. (2021-10-18). "New insights into the ~ 74 ka Toba eruption from sulfur isotopes of polar ice cores". Climate of the Past. 17 (5): 2119–2137. Bibcode:2021CliPa..17.2119C. doi:10.5194/cp-17-2119-2021. ISSN 1814-9324. S2CID 239203480.

- Takarada, Shinji; Hoshizumi, Hideo (23 June 2020). "Distribution and Eruptive Volume of Aso-4 Pyroclastic Density Current and Tephra Fall Deposits, Japan: A M8 Super-Eruption". Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 170. Bibcode:2020FrEaS...8..170T. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.00170. S2CID 219827774.

- Froggatt, P. C.; Nelson, C. S.; Carter, L.; Griggs, G.; Black, K. P. (13 February 1986). "An exceptionally large late Quaternary eruption from New Zealand". Nature. 319 (6054): 578–582. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..578F. doi:10.1038/319578a0. S2CID 4332421.

The minimum total volume of tephra is 1,200 km³ but probably nearer 2,000 km³, ...

- Bryan, Scott E.; Teal R. Riley; Dougal A. Jerram; Christopher J. Stephens; Philip T. Leat (2002). "Silicic volcanism: An undervalued component of large igneous provinces and volcanic rifted margins" (PDF). Geological Society of America (Special Paper 362). Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- Bailet, R. A. & Carr, R. G. (1994). "Physical geology and eruptive history of the Matahina Ignimbrite, Taupo Volcanic Zone, North Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 37 (3): 319–344. doi:10.1080/00288306.1994.9514624.

- Siebert, Lee; Simkin, Tom; Kimberly, Paul (9 February 2011). Volcanoes of the World: Third Edition. ISBN 9780520947931.

- Briggs, R.M.; Gifford, M.G.; Moyle, A.R.; Taylor, S.R.; Normaff, M.D.; Houghton, B.F.; Wilson, C.J.N. (1993). "Geochemical zoning and eruptive mixing in ignimbrites from Mangakino volcano, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 56 (3): 175–203. Bibcode:1993JVGR...56..175B. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90016-K.

- "Cerro Galan Caldera". Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- "Reykjanes". Global Volcanism Program. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- Gudmundsson, Magnús T.; Thórdís Högnadóttir (January 2007). "Volcanic systems and calderas in the Vatnajökull region, central Iceland: Constraints on crustal structure from gravity data". Journal of Geodynamics. 43 (1): 153–169. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..153G. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.015.

- T. Thordarson & G. Larsen (January 2007). "Volcanism in Iceland in historical time: Volcano types, eruption styles and eruptive history" (PDF). Journal of Geodynamics. 43 (1): 118–152. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..118T. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.005.

- "Surtsey Nomination Report 2007" (PDF). Surtsey, Island. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- Cole, J.W. (1990). "Structural control and origin of volcanism in the Taupo volcanic zone, New Zealand". Bulletin of Volcanology. 52 (6): 445–459. Bibcode:1990BVol...52..445C. doi:10.1007/BF00268925. S2CID 129091056.

- L. M. Parson & I. C. Wright (1996). "The Lau-Havre-Taupo back-arc basin: A southward-propagating, multi-stage evolution from rifting to spreading". Tectonophysics. 263 (1–4): 1–22. Bibcode:1996Tectp.263....1P. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(96)00029-7.

- Krippner, Stephen J. P., Briggs, Roger M., Wilson, Colin J. N., Cole, James W. (1998). "Petrography and geochemistry of lithic fragments in ignimbrites from the Mangakino Volcanic Centre: implications for the composition of the subvolcanic crust in western Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 41 (2): 187–199. doi:10.1080/00288306.1998.9514803.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The South Aegean Active Volcanic Arc: Present Knowledge and Future Perspectives By Michaēl Phytikas, Georges E. Vougioukalakis, 2005, Elsevier, 398 pages, ISBN 0-444-52046-5