Linois-class cruiser

The Linois class comprised three protected cruisers of the French Navy built in the early 1890s; the three ships were Linois, Galilée, and Lavoisier. They were ordered as part of a naval construction program directed at France's rivals, Italy and Germany, particularly after Italy made progress in modernizing its own fleet. The plan was also intended to remedy a deficiency in cruisers that had been revealed during training exercises in the 1880s. As such, the Linois-class cruisers were intended to operate as fleet scouts and in the French colonial empire. The ships were armed with a main battery of four 138.6 mm (5.46 in) guns supported by two 100 mm (3.9 in) guns and they had a top speed of 20.5 knots (38.0 km/h; 23.6 mph).

Galilée at anchor sometime before 1909 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Linois class |

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Friant class |

| Succeeded by | Descartes class |

| Built | 1892–1898 |

| In commission | 1895–1920 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Retired | 3 |

| General characteristics (data for Linois) | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | 2,285 to 2,318 long tons (2,322 to 2,355 t) |

| Length | 98 m (321 ft 6 in) (o/a) |

| Beam | 10.62 m (34 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 5.44 m (17 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 20.5 knots (38.0 km/h; 23.6 mph) |

| Complement | 250–269 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

All three members of the class served with the Mediterranean Squadron upon entering service in the mid-to-late 1890s. During this period, they were primarily occupied with peacetime training maneuvers. Lavoisier was transferred to the Newfoundland and Iceland Naval Division in 1903, where she patrolled fisheries for the next decade. After uneventful careers, Linois and Galilée were discarded in 1910 and 1911, respectively, having spent less than fifteen years in service. Lavoisier was the only member of the class still in commission at the start of World War I in August 1914, and she was used to patrol for German warships and submarines in various secondary theaters, ending the war in the Syrian Naval Division, where she remained through the end of the war. She was ultimately struck from the naval register in 1920 and thereafter broken up.

Design

In the late 1880s, the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) accelerated construction of ships for its fleet and reorganized the most modern ironclad battleships—the Duilio and Italia classes—into a fast squadron suitable for offensive operations. These developments provoked a strong response in the French press. The Budget Committee in the French Chamber of Deputies began to press for a "two-power standard" in 1888, which would see the French fleet enlarged to equal the combined Italian and German fleets, then France's two main rivals on the continent. This initially came to nothing, as the supporters of the Jeune École doctrine called for a fleet largely based on squadrons of torpedo boats to defend the French coasts rather than an expensive fleet of ironclads. This view had significant support in the Chamber of Deputies.[1]

The next year, a war scare with Italy led to further outcry to strengthen the fleet. To compound matters, the visit of a German squadron of four ironclads to Italy confirmed French concerns of a combined Italo-German fleet that would dramatically outnumber their own. Training exercises held in France that year demonstrated that the slower French fleet would be unable to prevent the faster Italian squadron from bombarding the French coast at will, in part because it lacked enough cruisers (and doctrine to use them) to scout for the enemy ships.[2]

To correct the weaknesses of the French fleet, on 22 November 1890, the Superior Council authorized a new construction program directed not at simple parity with the Italian and German fleets, but numerical superiority. In addition to twenty-four new battleships, a total of seventy cruisers were to be built for use in home waters and overseas in the French colonial empire. The Linois class were ordered as part of the program,[2][3] and their design was based on the earlier Forbin class, albeit with increased freeboard.[4][5]

General characteristics and machinery

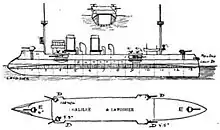

The ships of the Linois class varied slightly in dimensions; Linois was 98 m (321 ft 6 in) long overall, while Lavoisier and Galilée were 100.63 m (330 ft 2 in) long. Linois and Lavoisier had a beam of 10.62 m (34 ft 10 in), while Galilée was slightly wider, at 10.97 m (36 ft). All three ships had a draft of 5.44 m (17 ft 10 in). They displaced 2,285 to 2,318 long tons (2,322 to 2,355 t). Like most French warships of the period, the Linois-class cruisers' hulls had a pronounced ram bow and tumblehome shape. They also had a short forecastle deck , and the hulls included a double bottom. The ships had a minimal superstructure, with a small conning tower and a bridge forward and a smaller, secondary bridge aft. They were fitted with pole masts with spotting tops for observation and signaling purposes. Their crew varied over the course of their careers, amounting to 250–269 officers and enlisted men.[4][6]

The ships' propulsion system consisted of a pair of vertical triple-expansion steam engines driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by six coal-burning fire-tube boilers for Linois, while the other two vessels received sixteen coal-fired, Belleville-type water-tube boilers. All of the ships' boiler rooms were ducted into two funnels. Their machinery was rated to produce 6,800 indicated horsepower (5,100 kW) for a top speed of 20.5 knots (38.0 km/h; 23.6 mph). Coal storage amounted to 400 long tons (410 t) for Linois and 339 long tons (344 t) for Lavoisier and Galilée.[4] They had a cruising radius of 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) and 600 nmi (1,100 km; 690 mi) at 20.5 knots.[7]

Armament and armor

The ships were armed with a main battery of four 138.6 mm (5.5 in) 45-caliber guns in individual pivot mounts with gun shields, all in sponsons located amidships with two guns per broadside.[4] These were probably the M1893 variant installed without trunnions. They fired a variety of shells, including solid, 30 kg (66 lb) cast iron projectiles, and 35 kg (77 lb) explosive armor-piercing (AP) and semi-armor-piercing (SAP) shells with a muzzle velocity of 730 to 770 m/s (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s).[8] The forward pair were placed just abaft the conning tower and the after pair were between the aft funnel and the main mast. The main battery was supported by a secondary battery that consisted of a pair of 100 mm (3.9 in) Modèle 1891 guns, one at the bow and the other at the stern, which were also fitted with shields.[4] The guns fired 14 kg (31 lb) cast iron and 16 kg (35 lb) AP shells with a muzzle velocity of 710 to 740 m/s (2,300 to 2,400 ft/s).[9]

For close-range defense against torpedo boats, they carried eight 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns, two 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and four 37 mm Hotchkiss revolver cannon. These were carried in individual pivot mounts and they were distributed along the length of the ship to provide wide fields of fire. All three ships were also armed with four 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes in their hull above the waterline. The torpedoes were the M1892 variant, which carried a 75 kg (165 lb) warhead and had a range of 800 m (2,600 ft) at a speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).[4][10] Linois and Galilée had provisions to carry up to 120 naval mines.[4]

Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 40 mm (1.6 in) thick. Above the deck at the sides, a cofferdam filled with cellulose was intended to contain flooding from damage below the waterline. Below the main deck, a thin splinter deck covered the propulsion machinery spaces to protect them from shell fragments. Their forward conning towers had 138 mm (5 in) thick plating on the sides. The gun shields for the main battery were 75 mm (3 in) thick, while the secondary guns received 50 mm (2 in) thick shields.[4]

Construction

| Name | Laid down[4] | Launched[11] | Completed[4] | Shipyard[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linois | August 1892 | 30 January 1894 | 1895 | Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, La Seyne-sur-Mer |

| Galilée | 1893 | 28 April 1896 | September 1897[12] | Arsenal de Rochefort, Rochefort |

| Lavoisier | January 1895 | April 1897 | April 1898 | Arsenal de Rochefort, Rochefort |

Service history

Linois was assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron in 1896,[13] where she was joined by Galilée and Lavoisier in 1898. The three ships served as part of the cruiser force of the main French battle fleet. They took part in training exercises during this period, which sometimes included joint maneuvers with the Northern Squadron, along with shooting practice and naval reviews.[14][15][16] Linois was involved in a show of force meant to intimidate the Ottoman Empire in 1902 during a period of tension with France.[17] Lavoisier was transferred to the Newfoundland and Iceland Naval Division in 1903, where she patrolled fishing grounds off the coast of Newfoundland.[18] Linois remained in service with the Mediterranean Squadron through 1905.[19] During a review in 1909, Galilée hosted President Armand Fallières and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia during the latter's visit to France.[20] Linois was struck from the naval register in 1910, thereafter being broken up for scrap. Galilée was discarded the following year.[11]

Lavoisier was attached to the 2nd Light Squadron in the English Channel at the start of World War I in August 1914, but she saw no action there. She was transferred to the eastern Mediterranean in December 1915, operated briefly with the main French fleet, and then conducted anti-submarine patrols in the western Mediterranean. In 1917, she returned to the Moroccan Naval Division, and the following year, she was reassigned to the Syrian Naval Division, where she remained through the end of the war. In April 1919, Lavoisier was detached from the Syrian Division; decommissioned for the last time in August, she was struck from the naval register in early 1920 and sold to ship breakers.[21]

Citations

- Ropp, p. 195.

- Ropp, pp. 195–197.

- Campbell, pp. 310–311.

- Campbell, p. 310.

- Dorn & Drake, p. 49.

- Dorn & Drake, p. 50.

- France, p. 33.

- Friedman, p. 224.

- Friedman, p. 225.

- Friedman, p. 345.

- Smigielski, p. 193.

- Service Performed, p. 299.

- Thursfield, pp. 164–167.

- Brassey 1899, p. 71.

- Leyland, p. 64.

- Meirat, p. 21.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 218–219.

- Meirat, pp. 21–22.

- Brassey 1905, p. 42.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 232.

- Meirat, pp. 22–23.

References

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1905). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 40–57. OCLC 496786828.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Dorn, E. J. & Drake, J. C. (July 1894). "Notes on Ships and Torpedo Boats". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XIII: 3–78. OCLC 727366607.

- "France". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XV: 27–41. July 1896. OCLC 727366607.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 63–70. OCLC 496786828.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. Akron: F. P. D. S. III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "Service Performed by French Vessels Fitted with Belleville Boilers". Notes on Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. 20: 299. July 1901. OCLC 699264868.

- Smigielski, Adam (1985). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 190–220. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Naval Maneouvres in 1896". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 140–188. OCLC 496786828.