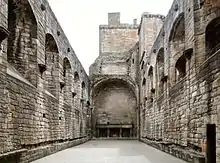

Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, 15 miles (24 km) west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Scotland in the 15th and 16th centuries. Although maintained after Scotland's monarchs left for England in 1603, the palace was little used, and was burned out in 1746. It is now a visitor attraction in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.

.jpg.webp)

Origins

A royal manor existed on the site from the 12th century.[1]

This was later enclosed by a timber palisade and outer fosse to create a fortification known as 'the Peel', built in 1301/2[2] by occupying English forces under Edward I. The site of the manor made it an ideal military base for securing the supply routes between Edinburgh Castle and Stirling Castle. The English fort was begun in March 1302 under the supervision of two priests, Richard de Wynepol and Henry de Graundeston, to the designs of Master James of St George, who was also present.[3] In September 1302, sixty men and 140 women helped dig the ditches; the men were paid twopence and the women a penny daily.[4] One hundred foot-soldiers were still employed as labourers on the castle in November and work continued during the Summer of 1303.[5]

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, a daughter of Edward I, was at Linlithgow Palace in July 1304. She was pregnant and travelled to Knaresborough Castle in England to have her child.[6] In September 1313, Linlithgow Peel was retaken for Scotland by an ordinary Scot named William Bynnie[7] or Bunnock[8] who was in the habit of selling hay to the garrison of the peel.[9] When the gate was opened for him, he halted his wagon so that it could not be closed, and he and his seven sons leapt out from their hiding place under the hay, and they captured the peel for King Robert the Bruce. King Robert sent reinforcements and had the peel dismantled so that it could not be retaken by the English.[10]

In January 1360, King David II visited Linlithgow and the peel was repaired 'for the king's coming'.[11]

In 1424, the town of Linlithgow was partially destroyed in a great fire.[12] King James I started the rebuilding of the Palace as a grand residence for Scottish royalty, also beginning the rebuilding of the Church of St Michael immediately to the south of the palace: the earlier church had been used as a storeroom during Edward's occupation.[13] James I set out to build a palace rather than a heavily fortified castle, perhaps inspired by Sheen Palace which he probably visited in England.[14] Mary of Guelders, the widow of James II and mother of James III, made improvements in 1461, for the visit of the exiled Henry VI of England.[15] Over the following century the palace developed into a formal courtyard structure, with significant additions by James III and James IV.

James IV and Margaret Tudor

James IV bought crimson satin for a new doublet to wear while formally welcoming the Spanish ambassador Don Martin de Torre at Linlithgow in August 1489. Silverware and tapestries were brought from Edinburgh for the event, and the wardrobe servant David Caldwell brought cords and rings to hang the tapestry in the palace. New rushes were brought from the Haw of Lithgow for the chamber floor. Entertainment included a play performed by Patrick Johnson and his fellows.[16] After a visit to Stirling the king returned to Linlithgow and played dice with the Laird of Halkett and his Master of Household, and on 17 September rewarded stonemasons working on the palace with two gold angel coins.[17] In November 1497 he played cards and bought jesses and leashes to go hawking. James gave the masons working on the building a tip of 9 shillings, known as "drinksilver", and ordered the master mason to go to Stirling Castle to provide a plan for his new lodgings there. Andrew Cavers, Abbot of Lindores, was made supervisor of construction at Linlithgow.[18]

James IV spent Easter 1490 at the palace, visited the town of Culross, and returned on 18 April to play dice with the Earl of Angus and the Laird of Halkett, losing 20 gold unicorn coins.[19] The king spent Christmas 1490 and Easter 1491 at Linlithgow. On 9 April he bought seeds for the palace gardener. The poet Blind Harry came to court at Linlithgow at least five times. James IV was interested in medicine and experimented taking blood from his servant Domenico and another man at Linlithgow.[20] Perkin Warbeck was a Christmas guest in 1495.[21] The king's mistress Margaret Drummond stayed at Linlithgow in the autumn of 1496.[22] The park dykes were rebuilt in 1498.[23]

On 31 May 1503 the palace was given to Margaret Tudor the bride of James IV.[24] A mason, Nichol Jackson, completed battlements on the west side of the palace in the summer of 1504. An African drummer known as the "More taubronar" performed at the palace.[25] When the king stayed at Linlithgow in July 1506 a coat was bought for a fool, and James IV visited the building work at the quire of St Michael's Church. He gave the master mason a tip of 9 shillings.[26] The son of James IV and Margaret Tudor, the future James V, was born in the palace in April 1512. The captain of the palace, Alexander McCulloch of Myreton, took on the role of the prince's bodyguard.[27]

The household of Margaret Tudor at Linlithgow included the African servants Margaret and Ellen More.[28] In April 1513 the roof of the chapel was altered and renewed, and a new organ was made by a French musician and craftsman called Gilyem and fixed to the wall. Timber was shipped to Blackness Castle and carted to the Palace. The windows of the queen's oratory, overlooking the Loch, were reglazed.[29] An English diplomat, Nicholas West, came to the palace in April 1513 and was met by Sir John Sinclair, one of the courtiers featured in William Dunbar's poem Ane Dance in the Quenis Chalmer.[30] West talked to Margaret Tudor and saw the baby Prince. He wrote "verily, he is a right fair child, and a large of his age".[31]

After the death of his father at the Battle of Flodden, the infant James V was not kept at Linlithgow, but came to the Palace from Stirling Castle dressed in a new black velvet suit accompanied by minstrels in April 1517, and went on to take up residence in Edinburgh Castle.[32] Margaret Tudor rewarded the king's nurse and governess, Marion Douglas, with a grant of the lands near Linlithgow palace called the Queen's Acres in July 1518. Marion's daughter, Katherine Bellenden, made the king's shirts.[33]

James V

When the teenage James V came to Linlithgow in 1528, Thomas Hamilton supplied him with sugar candy.[34] James V added the outer gateway and the elaborate courtyard fountain.[35] The stonework of the south façade was renewed and unified for James V in the 1530s by the keeper, James Hamilton of Finnart.[36] Timber imported from Denmark-Norway, including "Estland boards" and joists, was bought at the harbours of Dundee, South Queensferry, Montrose, and Leith, and shipped to Blackness Castle to be carted to the Palace. Three oak trees were cut down in Callender Wood to provide tables for dressing food in the kitchens, and seven oak trees from the Torwood. The improvements included altering the chapel ceiling and trees were brought from Callender to make scaffolding for this. Six hogshead barrels were bought to hold the scaffold in place.[37]

The older statues of the Pope, the Knight, and Labouring Man on the east side of the courtyard, with the inscriptions on ribbons held by angels were painted. New iron window grills, called yetts, were made by blacksmiths in Linlithgow, and these, with weather vanes, were painted with red lead and vermilion. A metal worker in Glasgow called George Clame made shutter catches for the windows and door locks in iron plated with tin. The chapel ceiling was painted with fine azurite. Thomas Peebles put stained glass in the chapel windows and the windows of the "Lyon Chamber", meaning the courtyard windows of the Great Hall.[38]

A chaplain, Thomas Johnston, kept the palace watertight and had the wallwalks and gutters cleaned. Robert Murray looked after the lead roofs and the plumbing of the fountain.[39] There was a tennis court in the garden and an eel-trap in the Loch.[40] The lodgings built for the queen in the 1530s may have been in the old north wing on the first floor. Only one side of a doorway from this period remains, which may have led to a grand staircase for the queen.[41] When Mary of Guise arrived in Scotland, James Hamilton of Finnart was given 400 French gold crowns to repair the palace.[42] In August 1539 he was paid for rebuilding the king's kitchen, at the north end of the great hall, with a fireplace, an oven, and a room for silver vessels, and another for keeping coal.[43]

During a visit in December 1539, Mary of Guise was provided with gold, silver, and black thread for embroidery, and her ladies' embroidery equipment was brought from Falkland Palace. Tapestry was brought from Edinburgh to decorate the palace. The goldsmiths Thomas Rynde and John Mosman provided chains, tablets or lockets, rings, precious stones, necklaces, and jewelled coifs for ladies called "shaffrons" for the king to give as gifts to his courtiers on New Year's Day. On the feast of the Epiphany in January the court watched an "interlude" that was an early version of David Lindsay's play, A Satire of the Three Estates, in the Great Hall. Mary of Guise returned to Edinburgh on 3 February and was crowned soon afterwards.[44]

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots, was born at Linlithgow Palace in December 1542 and lived at the palace for a time. In January 1543 Viscount Lisle heard that she was kept with her mother, "and nursed in her own chamber".[45] In March 1543 the English ambassador Ralph Sadler rode from Edinburgh to see her for the first time. Mary of Guise showed him the queen out of her swaddling and Sadler wrote that the infant was "as goodly a child I have seen, and like to live".[46] The Earl of Lennox came to see the infant queen on 5 April 1543.[47]

The blacksmith William Hill was employed at this time to increase the security of the palace by fitting iron window grills, called yetts. Lord Livingstone was paid £813 for keeping the infant queen in the palace.[48] Regent Arran was worried his enemies, including Cardinal Beaton, would take Mary in July 1543. He came with the Earl of Angus and brought his artillery. He considered putting the queen in Blackness Castle, a stronger fortress. Henry VIII hoped that Mary would be separated from her mother and taken to Tantallon Castle. Mary was teething and plans to move her were delayed.[49]

Supporters of the Auld Alliance at Linlithgow signed the "Secret Bond" pledging to prevent Mary marrying Prince Edward.[50] Following lengthy negotiations between the armed factions at Linlithgow, Mary was taken to Stirling Castle by her mother on 26 July 1543, escorted by the Earl of Lennox,[51] and an armed force described as a "great army".[52] Arran employed a carpenter from Linlithgow, Thomas Milne, to make three wooden chandeliers to hang in the palace in January 1546.[53]

As an adult Queen Mary often visited Linlithgow, but did not commission new building work at the palace. She returned on 14 January 1562 with her half-brother Lord James Stewart and received the Earl of Arran as a guest. She returned to Edinburgh on 30 January after visiting Cumbernauld Castle.[54] Lord Darnley, her second husband, played tennis at Linlithgow.[55] Mary came to Linlithgow in December 1565 to take the air and have a quiet time with few visitors, but her husband Lord Darnley was expected. She was pregnant and was carried to Linlithgow in a horse-litter.[56] She had a bed at Linlithgow of crimson velvet and damask embroidered with love knots.[57]

James VI

In the years after the abdication of Mary and the Marian Civil War, Captain Andrew Lambie and his lieutenant John Spreul kept an armed guard of 28 men of war at the Palace. An iron yett was brought to the Palace from Blackness Castle by Alexander Stewart in 1571.[58] Timber was used to fortify the church steeple.[59]

In March 1576 Regent Morton ordered some repairs to the roof and the kitchen chimney.[60] James VI of Scotland came to Linlithgow in May 1583, and his courtiers, including the Earl of Bothwell and the Earl Marischal played football.[61] James VI held a parliament in the great hall of the palace in December 1585, the first gathering of the whole nobility in the palace since the reign of his grandfather James V of Scotland.[62] James VI gave lands including the palace to his bride Anne of Denmark as a "morning gift". On 14 May 1590 Peder Munk, the Admiral of Denmark, rode to Linlithgow from Niddry Castle, and was welcomed at the palace by the keeper Lewis Bellenden. He took symbolic possession or (sasine) by accepting a handful of earth and stone.[63]

The keeper of the palace in 1594 was the English courtier Roger Aston who repaired the roof using lead shipped from England.[64] Roger Aston was of doubtful parentage and as a joke hung a copy of his family tree next to that of the king of France in the long gallery, which James VI found very amusing.[65] There was a private stair accessing the king's apartments, and the Laird of Dundas claimed to have encountered the queen there in the dark without recognising her.[66]

In January 1595 the Earl of Atholl, Lord Lovat, and Kenneth Mackenzie were kept prisoners in the palace, in order to pacify "Highland matters".[67] Lord Lovat gained the king's favour and soon after married one of Anne of Denmark's ladies in waiting, Jean Stewart, a daughter of Lord Doune.[68] Roger Aston helped the queen move to Linlithgow Palace at the end of May 1595.[69] Over several days at Linlithgow in June 1595, James VI and Anne had discussions about the keeping of their son Prince Henry by the Earl of Mar. Anne refused to talk to Mar when he came to Linlithgow.[70]

The daughter of James VI and Anne, Princess Elizabeth, lived in the Palace in the care of Helenor Hay, Countess of Linlithgow, helped by Mary Kennedy, Lady Ochiltree.[71] Alison Hay was her nurse, helped by her sister Elizabeth Hay.[72] John Fairny was appointed to guard her chamber door.[73] In 1599 James VI had to write to the Linlithgow burgh council about townspeople who had built houses which obstructed a route taken by the royal horses to water, and houses and gardens built near the loch (in recent times of drought) which hindered the royal laundry.[74]

Anne of Denmark came to visit Princess Elizabeth at Linlithgow Palace on 7 May 1603, and then rode to Stirling Castle, where she argued with the Countess of Mar and the Master of Mar over the custody of Prince Henry.[75] She brought Prince Henry to Linlithgow on 27 May, and after a week in Edinburgh, went to London.[76] In 1616 the Earl of Linlithgow said there was still a tapestry from the royal collection at Linlithgow, used in Prince Henry's chamber. The tapestry had been damaged by the fool Andrew Cockburn. The Earl had decorated Princess Elizabeth's rooms with his own tapestry.[77]

Decay and repair

After the Union of the Crowns in 1603 the Royal Court became largely based in England and Linlithgow was used very little. The North Range, said to be in very poor condition in 1583,[78] and "ruinous" in 1599,[79] collapsed at 4am on 6 September 1607. The Earl of Linlithgow wrote to King James VI & I with the news:

Please your most Sacred Majestie; this sext of September, betuixt thre and four in the morning, the north quarter of your Majesties Palice of Linlithgw is fallin, rufe and all, within the wallis, to the ground; but the wallis ar standing yit, bot lukis everie moment when the inner wall sall fall and brek your Majesties fontane."[80]

King James had the north range rebuilt between 1618 and 1622. The carving was designed by the mason William Wallace. In July 1620, the architect, James Murray of Kilbaberton, estimated that 3,000 stones in weight of lead would be needed to cover the roof, costing £3,600 in Pound Scots (the Scottish money of the time).[81]

After the death of the depute-treasurer Gideon Murray who was supervising the project, King James put the Earl of Mar in charge of the "speedy finishing of our Palace of Linlithgow". On 5 July 1621 the Earl of Mar wrote to James to tell him he had met James Murray, the master of works, and viewed the works at "grate lenthe". Mar said the Palace would be ready for the King at Michaelmas. King James planned to visit Scotland in 1622, but never returned.[82]

The carving at the window-heads and the Royal Arms of Scotland on the new courtyard façade were painted and gilded, as were the old statues of the Pope, Knight, and Labouring Man on the east side.[83] In 1629 John Binning, James Workman, and John Sawyers painted the interiors with decorative friezes above walls left plain for tapestries and hangings.[84] Despite these efforts, the only reigning monarch to stay at Linlithgow after that date was King Charles I, who spent a night there in 1633. As part of the preparations, the burgh council issued a proclamation forbidding the wearing of plaids and blue bonnets, a costume deemed "indecent".[85]

In 1648, part of the new North Range was occupied by The 2nd Earl of Linlithgow.[86] An English visitor in October 1641 recorded in a poem that the roof of the great hall was already gone, the fountain vandalised by those who objected on religious grounds to the motto "God Save the King," but some woodcarving remained in the Chapel Royal.[87]

The palace was again described as ruinous in 1668. Its swansong came in September 1745, when Bonnie Prince Charlie visited Linlithgow on his march south but did not stay overnight. It is said that the fountain was made to flow with wine in his honour.[88] The Duke of Cumberland's army destroyed most of the palace buildings by accidentally burning it through lamps left on straw bedding on the night of 31 January/1 February 1746.

Keepers and Captains of the Palace

The positions of official keeper and captain of the palace have been held by: Andrew Cavers, Abbot of Lindores, 1498;[89] John Ramsay of Trarinzeane, 1503;[90] James Hamilton of Finnart, 1534, Captain and Keeper; William Danielstoun from 19 November 1540; Robert Hamilton of Briggis, from 22 August 1543; Andrew Melville of Murdocairney, later Lord Melville of Monimail, brother of James Melville of Halhill, from 15 February 1567; George Boyd, deputy Captain, 1564; Andrew Ferrier, Captain of the Palace, 1565, Frenchman and archer of the Queen's Guard;[91] John Brown, June 1569; Andrew Lambie, June 1571;[92] Ludovic Bellenden of Auchnoul 22 November 1587, and 1595 Roger Aston. The office was acquired by Alexander Livingstone, 1st Earl of Linlithgow, and remained in that family until 1715 when the rights returned to the Crown.[93]

A Scottish heraldic manuscript known as The Deidis of Armorie dating from the late 15th-century and derived and translated from a variety of sources, outlines the duties of keepers and captains:

"The capitanys war ordanit be princis to keip the fortrassis and gud townys of the princis and to vittaill thaim and garnys thaim of al necessar thingis petenyng to the wer; ... and gar mak certane and sur wachis be him and his folkis, baith be nycht and day, ffor dout of ganfalling in pestilence, sua that he may rendre gud compt of the place quhen tym and place requiris"

(modernised) The Captains were ordained by princes to keep the fortresses and good towns of the princes, and to stock them with food and furnish armaments in case of war; ... and to make sure and certain watch, himself and his kinsfolk, both by night and day, For fear of succumbing to the plague, so that he may render good account of the place, when time and place requires.[94]

Present day

Long-neglected, the palace passed into the care of HM Commissioners for Woods and Forests, together with the surrounding grounds, in 1832. It passed to HM Office of Works in 1874. Major consolidation works were undertaken in the 1930s and 1940s.[95]

Today the palace is managed and maintained by Historic Environment Scotland. The site is open to visitors all year round, usually subject to an entrance fee for non-members, but on occasion the entry fee is waived during the organisation's "Doors open days".[96] In summer the adjacent 15th-century parish church of St Michael is open for visitors, allowing a combined visit to two of Scotland's finest surviving medieval buildings. The site was visited by 103,312 people in 2019.[97]

For over 40 years, tours of the palace for children are led by 'Junior Guides', pupils at Linlithgow Primary School[98]

A Strathspey for bagpipes was composed in honour of Linlithgow Palace.[99]

The Palace is said to be haunted by the spectre of Mary of Guise, mother to Mary, Queen of Scots.[100]

Artistic and cultural uses

On 4 December 2012, the French fashion house Chanel held its tenth Métiers d’Art show in the palace. The collection, designed by Karl Lagerfeld, was called 'Paris-Édimbourg' and inspired by classic Scottish styling using tweed and tartan fabrics worn by models Stella Tennant, Cara Delevingne, and Edie Campbell.

The show renewed media interest in the possibility of restoring the roof of the palace.[101]

In August 2014, a music festival was held on the palace's grounds called 'Party at the Palace'. This became a yearly event and again took place in 2015; from 2016 it was moved to the other side of the loch due to its popularity and need for more space. The festival still boasts views of the palace.

Some scenes in the time-traveling romance TV series Outlander are set at a fictional castle for which Linlithgow Palace stands in; this has attracted a number of international tourists.[102]

References

- "Linlithgow Palace: Property detail". Historic Scotland.

- Linlithgow Palace – Official Guide 1948

- Notices of Original Documents illustrative of Scottish History, Maitland Club, (1841), 67–83, (headings only).

- Accounts of the Master of Works, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), p. lxvi (Latin).

- Simpson, Grant, & Galbraith, James, ed., Calendar Documents Scotland in PRO and British Library, vol. 5 supplementary, SRO (n.d), no. 305, no. 472 (h, j, u), 'j' mentions Robert de Wynpol (Wimpole) working in Summer 1303, 472 (k) mentions the Warwolf lupus-guerre siege engine at Stirling Castle.

- Christopher Woolgar, The Great Household in Late Medieval England (Yale, 1999), p. 98.

- John B. Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, vol. 2 (H. Colburn, 1850), pp. 168

- Inglis, John (July 1915). "Edinburgh during the Provostship of Sir William Binning, 1675–1677". Scottish Historical Review. 12 (48): 369–387. JSTOR 25518844. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- George Waldie, A History of the Town and Palace of Linlithgow (Linlithgow, 1868), p. 25.

- Scott, Ronald McNair (1982). Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. Edinburgh, Scotland: Canongate Publishing. p. 133.

- Penman, Prof. Michael (2004). David II. East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell Press Ltd. p. 259.

- British Castle – Linlithgow Palace History

- "St Michael's Church Feature Page". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- John G. Dunbar, Scottish Royal Palaces (East Linton: Tuckwell, 1999), p. 8.

- Marilyn Brown, Scotland's Lost Gardens (Edinburgh, 2015), pp. 63, 71.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 117–8, 132–3, 142.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 120.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 366–9.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 132–3.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 175–6: Anne McKim, The Wallace (Canongate, 2003), p. viii.

- William Hepburn, The Household and Court of James IV of Scotland (Boydell, 2023), p. 67.

- Marilyn Brown, Scotland's Lost Gardens (Edinburgh, 2015), p. 71: Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 323.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 380.

- Foedera, vol. 8, p. 71: Joseph Bain, Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, 1357–1509, Addenda 1221–1435, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1888), p. 344 no. 1713

- Imtiaz Habib, Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Routledge, 2017): Accounts of the Treasurer, 1500–1504, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 440, 444.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, 1506–1507, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1901), pp. 204–5.

- William Hepburn, The Household and Court of James IV of Scotland (Boydell, 2023), p. 134.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1902), pp. 339, 324, 401, 404.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1902), pp. 442, 523–5.

- Michelle Beer, Queenship at the Renaissance Courts of Britain (Woodbridge, 2018), p. 93.

- Henry Ellis, Original Letters, vol. 1 (London, 1824), p. 74.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1903), p. 111.

- HMC 14th Report, part III: Roxburghe, vol. 1 (London), pp. 28–9: The Douglas Book, vol. 3, p. 388.

- Excerpta e libris domicilii Jacobi Quinti regis Scotorum (Bannatyne Club: Edinburgh, 1836), p. 169.

- John G. Dunbar, Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell/Historic Scotland/RCAHMS: East Linton, 1999), pp. 6–21.

- Henry Paton, Accounts of the Masters of Work: 1529–1615, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 115–131.

- Henry Paton, Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 123–6.

- Henry Paton, Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 126–7, 128.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), pp. 335, 339.

- David Hay Fleming & James Beveridge, Register of the Privy Seal, 1542–1548, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 67 no. 460.

- Charles McKean, 'Gender Differentiation in Scottish Royal Palaces', Monique Chatenet & Krista De Jonge, Le prince, la princesse et leurs logis (Paris, 2014), p. 94.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 60.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 195.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), pp. 264–5, 266–7, 287: State Papers of Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont. (London, 1836), pp. 170–1.

- Sadler State Papers, iv part 2 (London, 1836), p. 240.

- Arthur Clifford, Sadler State Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1809), pp. 86–8

- Joseph Bain, Hamilton Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1890), p. 510.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1908), pp. 177, 188, 192, 224.

- Arthur Clifford, Sadler State Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1809), pp. 234–5, 240–1: Joseph Bain, Hamilton Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1890), pp. 551, 584.

- Letters and Papers Henry VIII, 18:1 (London, 1901), no. 945: Hamilton Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1890), p. 630 no. 446.

- E. K. Marshall, R. K., Mary of Guise (Collins, 1977), pp. 126–130: Marcus Merriman, The Rough Wooing (Tuckwell, 2000), pp. 124–126: Edward M. Furgol, 'Scottish Itinerary of Mary Queen of Scots', PSAS, vol. 107 (1989), pp. 119–231.

- Lucinda H. S. Dean, 'In the Absence of an Adult Monarch', Medieval and Early Modern Representations of Authority in Scotland and the British Isles (Routledge, 2016), p. 147.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, 1541–1546, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1908), p. 433.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 590–2, 597–8.

- Charles Thorpe McInnes, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland: 1566–1574, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1970), p. 383.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 241, 243, 245.

- Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), p. 136 item 19.

- Charles Thorpe McInnes, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, 1566-1574, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1970), pp. 250-1, 303.

- John Hill Burton, Register of the Privy Council, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1878), pp. 166-7.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 13 (Edinburgh, 1978), p. 157.

- Miles Kerr-Peterson, A Protestant Lord in James VI's Scotland: George Keith, Fifth Earl Marischal (Boydell, 2019), p. 32: William Boyd, Calendar of State Papers Scotland: 1581–1583, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1910), p. 475.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1914), p. 161.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (John Donald: Edinburgh, 1997), p. 103.

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), pp. 79, 87.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar of Border Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1894), pp. 563

- Letters to King James the Sixth from the Queen, Prince Henry, Prince Charles (Edinburgh, 1835), p. l.

- Annie Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 523, 526.

- William Mackay, Fraser Chronicles (Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 223–5.

- Letters of John Colville (Edinburgh, 1858), pp. 278–9.

- Annie Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1593–1595, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 615–6, 626.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol 10 (Edinburgh, 1891), p. 521: Mary Anne Everett Green, Elizabeth Queen of Bohemia (London, 1902), pp. 2–4.

- Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart: Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), p. 23.

- Letters to King James the Sixth from the Queen, Prince Henry, Prince Charles etc (Edinburgh, 1835), pp. lxxxiii, lxxxv

- George Waldie, A History of the Town and Palace of Linlithgow (Linlithgow, 1868), pp. 58–9.

- William Fraser, Memorials of the Earls of Haddington, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1889), p. 210

- David Calderwood, History of the Kirk of Scotland, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1845), p. 231.

- David Masson, Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1891), p. 521.

- Henry Paton, Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), p. 311: Linlithgow Palace, official guide (1948).

- Calendar State Papers Scotland vol. 13 part 2 (Edinburgh, 1969), p. 623.

- The Spottiswoode Miscellany, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1844), p. 369.

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1895), p. 335.

- HMC Mar & Kellie at Alloa House (London, 1904), pp. 95–96.

- Mackechnie, Aonghus, 'James VI's Architects', Michael Lynch & Julian Goodare, The Reign of James VI (Tuckwell, 2000), p. 168.

- John Imrie & John Dunbar, Accounts of the Masters of Works, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1982), p. 269.

- George Waldie, A History of the Town and Palace of Linlithgow (Linlithgow, 1868), p. 62.

- The Spottiswoode Miscellany, vol. 1 (1844), pp. 370–372.

- Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, 2 (Edinburgh, 1904), p. 275, anonymous poem, A Scottish Journie of Montague Bertie, Lord Willoughby.

- "'Wine' fountain to flow once more". BBC News. 26 June 2007.

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1908), p. 38 no. 296.

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1908), p. 134 no. 909.

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 5:2 (Edinburgh, 1957), p. 254 no. 3182: vol. 5:1, p. 696 no. 2421.

- Gordon Donaldson, Register of the Privy Seal: 1567–1574, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1963), p. 247 no. 1282.

- The Spottiswoode Miscellany, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1844), p. 355: Protocol book of Thomas Johnson (SRS, 1920), nos. 340, 709, 781, 839, 864.

- L. A. J. R. Houwen, The Deidis of Armorie, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Scottish Text Society, 1994), pp. xiii, 2.

- Linlithgow Palace: Official Guide Book 1948

- "Free weekend". Historic Scotland.

- "ALVA – Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- "Historic Environment". www.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Archie Cairns – Book 1 Pipe Music 'Linlithgow Palace' Strathspey 1995

- "Haunted trail of Mary, Queen of Scots – Scotsman.com News". The Scotsman. 8 December 2005.

- Chanel Paris-Edimbourg Archived 11 April 2013 at archive.today: Vogue Metiers d'Art: Scotsman Newspaper, 3 March 2013, 'Roof for Linlithgow'

- Baynes, Richard (15 February 2020). "'Outlander' TV Show Prompts Tourist Boom in Central Scotland". Weekend Edition Saturday. Retrieved 16 February 2020.