Lechovo

Lechovo (Greek: Λέχοβο), renamed as Iroiko (Greek: Ηρωϊκό) between 1955 and 1956,[2][3] is a village and a former community in Florina regional unit, Western Macedonia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Amyntaio, of which it is a municipal unit.[4] The municipal unit has an area of 22.844 km2,[5] and a population of 1,115 (2011 census). The village is set amongst the mountains of Northern Greece and the main road runs through the town's centre. There is a museum, a football pitch and an indoor handball stadium. Lechovo has stone architecture common to many northern villages, and has an old upper square and church bell tower.

Lechovo

Λέχοβο | |

|---|---|

| |

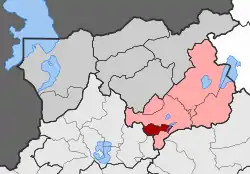

Lechovo Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 40°35′N 21°30′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Western Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Florina |

| Municipality | Amyntaio |

| • Municipal unit | 22.8 km2 (8.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 900 m (3,000 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 1,115 |

| • Municipal unit density | 49/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Vehicle registration | ΡΑ |

The village of Lehovo became inhabited in the mid-eighteenth century and some of its villagers worked as master builders.[6] In statistics gathered by Vasil Kanchov in 1900, Lechovo was populated by 750 Christian Albanians and 90 Aromanians.[7] Lechovo, with its population of hellenised Albanians, participated extensively on the Greek side of the Macedonian Struggle in the late Ottoman period.[8][9] Following the Young Turk Revolution, the Greek clergy's prominent position in places like Lechovo was contested by Aromanian and Albanian nationalists.[9] During the population exchange between Greece and Turkey (1923), Lechovo's pro-Greek sentiments resulted in Greek authorities removing it from consideration as a resettlement destination in the Florina region for incoming Greek Anatolian refugees.[10]

Lechovo had 1,194 inhabitants in 1981.[11] In fieldwork done by Riki Van Boeschoten in late 1993, Lechovo was populated by Arvanites.[11] Arvanitika (close to Albanian) was spoken in the village by people over 30 in public and private settings.[11] Children understood the language, but mostly did not use it.[11] Aromanian was spoken by people over 60, mainly in private.[11] In the early 2000s, the Tosk Albanian dialect was often spoken by village elders.[12]

Lechovo has not been influenced by the nearby predominant Slavic musical tradition of the area, and villagers have no knowledge of songs from their neighbours.[13] Dances performed in Lechovo are the Berati, Hasapia, Tsamiko, Kalamatiano, along with the Poustseno.[14]

Lechovo Church

Lechovo Church Macedonian Struggle Monument honouring Lechovo's participation

Macedonian Struggle Monument honouring Lechovo's participation Lechovo Folklore Museum

Lechovo Folklore Museum Traditional home items

Traditional home items Icons and other religious items

Icons and other religious items Traditional female clothing

Traditional female clothing

See also

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Name Changes of Settlements in Greece: Lechovon -- Iroikon". Pandektis. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "Name Changes of Settlements in Greece: Iroikon -- Lechovon". Pandektis. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "ΦΕΚ B 1292/2010, Kallikratis reform municipalities" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- Hart, Laurie Kain (2006). "Provincial Anthropology, Circumlocution, and the Copious Use of Everything". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 24 (2): 341. doi:10.1353/mgs.2006.0022. S2CID 144805728. "They praise, for example, its Albanian-speaking master builders from Lehovo (settled mid-18th century) Drosopigi (Belkameni) and Flambouro (Negovani)."

- Aarbakke 2015, pp. 3–4.

- Koliopoulos, John (1999). "Brigandage and Insurgency in the Greek Domains of the Ottoman Empire, 1853-1908". In Gondicas, Dimitri; Issawi, Charles (eds.). Ottoman Greeks in the Age of Nationalism: Politics, Economy, and Society in the Nineteenth Century. Darwin Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780878500963. "Lechovo, a village of hellenized Albanians in the Phlorina district".

- Aarbakke, Vemund (2015). "The Influence of the Orthodox Church on the Christian Albanians' national orientation in the Period Before 1912" (PDF). Albanohellenica. 6: 5.

- Kostopoulos, Tasos (2003). "Counting the 'Other': official census and classified statistics in Greece (1830-2001)". In Helmedach, Andreas; Höpken, Wolfgang; Maner, Hans-Christian (eds.). Jahrbücher f. Geschichte u. Kultur Südosteuropas 5. Slavica Verlag. p. 67.

- Van Boeschoten, Riki (2001). "Usage des langues minoritaires dans les départements de Florina et d'Aridea (Macédoine)" [Use of minority languages in the departments of Florina and Aridea (Macedonia)]. Strates. 10. para.1. "l’arvanitika (proche de l’albanais)"; Table 3: Lechovo, 1194, A, A2, V3; A = Arvanites, A = arvanitika, V = valaque (aroumain)"

- Albanian, Tosk at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- Moraitis 2008, p. 30.

- Moraitis, Thanasis (2008). "Η αρβανίτικη γλώσσα στα παραδοσιακά τραγούδια" [The Arvanitika language in traditional songs]. Ετερότητες και Μουσική στα Βαλκάνια [Otherness and Music in the Balkans] (PDF). Εκδόσεις ΤΕΙ Ηπείρου – ΚΕΜΟ. p. 32. ISBN 9789608932326.