Least seedsnipe

The least seedsnipe (Thinocorus rumicivorus) is a xerophilic species of bird in the Thinocoridae family.

| Least seedsnipe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Thinocoridae |

| Genus: | Thinocorus |

| Species: | T. rumicivorus |

| Binomial name | |

| Thinocorus rumicivorus Eschscholtz, 1829 | |

| |

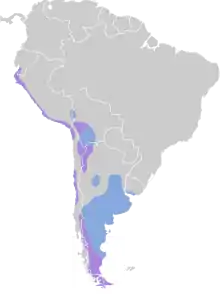

It breeds in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. They are common across South America and have been recorded in Ecuador, the Falkland Islands, Uruguay, Brazil, and as far away as Antarctica.[2] The range of the least seedsnipe is estimated to be about 1,300,000 km2.

Its natural habitats are temperate grassland, subtropical or tropical high-altitude grassland, and pastureland, but it can be found in habitats ranging from sandy beaches to the open steppe, and even some open deserts in northern Chile.[3][4]

Etymology

The least seedsnipe was described in 1829 by Eschscholtz. The genus name comes from the Greek thin-, thinos- (θινος) 'sand'or 'desert' and Latin 'corys' (from Greek κορυδος) 'lark'.[5] The species name comes from Latin rumicis “sorrel” and vorā “eater”.[6]

Taxonomy

There are three subspecies of the least seedsnipe:[7]

Description

The least seedsnipe is the smallest member of the Thinocoridae family.[8] They have short tails and long pointed wings. Their legs and toes are a dull greenish yellow. The beak of the least seedsnipe is an ashy color and is conical like that of a finch or a sand grouse.[4][9] Adult males have a gray face, neck, and breast, and have black lines at the center of the throat that form an inverted “T” shape.[2] The eyes are a dark gray color.[9]

Behavior

Male seedsnipe will commonly perch on a prominent bush or fence post to deliver nuptial calls that sound like a series of a “rapid pu-pu-pu-pu-pu”s, very similar to that of the Common Snipe.[10]

Seedsnipes are well-adapted to arid environments and show no increases in water loss between 20 and 36 °C. The thermoneutral zone extends from 33 to 38 °C in this species, but they have the capacity to dissipate heat through evaporative water loss up to 42 °C. Their metabolic rate is 38% lower than other non-passerine birds of similar body mass (~50 g), reducing the contribution to the total heat budget.[4]

Nesting

Only the female incubates the eggs. The average clutch size of the least seedsnipe is four eggs laid in a simple nest scrape, which the female buries using her feet (rather than her bill, as is seen in some African Charadrii) whenever she leaves the nest. If loose, dry plant material is available, she will use this to cover the hatchlings until her return. This behavior appears to have arisen independently in Thinocoridae. The primary purpose for nest covering in Thinocorus rumicivorus is most likely concealment from predators, but thermoregulation probably also plays a factor.[11]

Diet

As the common name suggests, least seedsnipes rely mostly on seeds, but they will also eat leaves and buds and as such are strictly vegetarian in their natural habitat. However, in captivity they have been known to eat mealworms. Unlike most Charadriiformes, least seedsnipes possess a crop, a gizzard and long intestinal caeca. They have been observed foraging from a crouched position, rapidly snapping off plants and swallowing the fragments whole. They also stretch to bite off the top of grasses and tall herbs and are well-suited to browsing.[12] They derive most if not all of their water needs from succulent plants and are only very rarely seen drinking water.[4][8] They visit the beds of Calceolaria uniflora (Scrophularaceae) and feed on the fleshy growths on the lower lips of the flower and in the process transfer pollen across flowers.[13]

Status and conservation

This species has an extremely large range and is one of the most common birds of southern Patagonia. According to the IUCN, the population appears stable. It has therefore been labeled as species of Least Concern.[1]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Thinocorus rumicivorus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22693046A93380643. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693046A93380643.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Favero, M., & Silva, M. P. (1998). First Record of the Least Seedsnipe Thinocorus rumicivorus in the Antarctic. Ornitologia Neotropical, 10, 107-109.

- Lane A. A. (1897) Field notes on the birds of Chili. Ibis 3, 297-3 17.

- Ehlers, R., and M. L. Morton (1982). Metabolic rate and evaporative water loss in the Least Seed-Snipe Thinocorus rumicivorus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 73A:233–235.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). "Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird-names". Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- “Thinocorus.”(2016). Animalia: Etymology of Animal Names. Web. Available at http://metazoa.us/thinocorus/. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Grebes, flamingos, buttonquail, plovers, painted-snipes, jacanas, plains-wanderer, seedsnipes". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Castro, F., J. Castro, A. R. Ferreira, M. A. Crozariol, and A. C. Lees (2012). A first documented Brazilian record of Least Seedsnipe Thinocorus rumicivorus Eschscholtz, 1829 (Thinocoridae). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 20:455–457.

- Grant, C. H. (1911). List of Birds collected in Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Southern Brazil, with Field‐notes. Ibis, 53(3), 459-478.

- Miller, E. H. (1996). Nuptial vocalizations of male Least Seedsnipe: Structure and evolutionary significance. The Condor, 98(2), 418-422.

- Maclean, G. L. (1974). Egg-covering in the Charadrii. Ostrich, 45(3), 167-174.

- Korzun, L. P., C. Érard, J.-P. Gasc, and F. J. Dzerzhinsky (2009). Adaptation of seedsnipes (Aves, Charadriiformes, Thinocoridae) to browsing: a study of their feeding apparatus. Zoosystema 31:347–368. doi: 10.5252/z2009n2a7

- Sérsic, A. N.; Cocucci, A. A. (1996). "A Remarkable Case of Ornithophily in Calceolaria : Food Bodies as Rewards for a Non-nectarivorous Bird*". Botanica Acta. 109 (2): 172–176. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.1996.tb00558.x.