Gag Law (Puerto Rico)

Law 53 of 1948 better known as the Gag Law,[1] (Spanish: Ley de La Mordaza) was an act enacted by the Puerto Rico legislature[lower-alpha 1] of 1948, with the purpose of suppressing the independence movement in Puerto Rico. The act made it a crime to own or display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to speak or write of independence, or to meet with anyone or hold any assembly in favor of Puerto Rican independence.[2] It was passed by a legislature that was overwhelmingly dominated by members of the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), which supported developing an alternative political status for the island. The bill was signed into law on June 10, 1948 by Jesús T. Piñero, the United States-appointed governor.[3] Opponents tried but failed to have the law declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court.

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

|

The law remained in force for nine years until 1957, when it was repealed on the basis that it was unconstitutional as protected by freedom of speech within Article II of the Constitution of Puerto Rico and the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

Prelude

After the United States invaded Puerto Rico in 1898 during the Spanish–American War, some leaders, such as José de Diego and Eugenio María de Hostos, expected the United States to grant the island its independence.[4][5] Instead, under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 ratified on December 10, 1898, the U.S. annexed Puerto Rico. Spain lost its American territories, and the United States gained imperial strength and global presence.[6]

In the early 20th century, the Puerto Rican independence movement was strong, growing, and embraced by multiple political parties. Among these were the Union Party of Puerto Rico founded in February 1904 by Luis Muñoz Rivera, Rosendo Matienzo Cintrón, Antonio R. Barceló, and José de Diego; the Liberal Party of Puerto Rico founded by Antonio R. Barceló; and the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party founded by José Coll y Cuchí.[7]

In 1914, the entire Puerto Rican House of Delegates demanded independence from the U.S. Instead, the U.S. imposed the Jones Act of 1917, which mandated U.S. citizenship on the entire island.[8] The passage of the Jones Act coincided with America's entry unto World War I, and it allowed the U.S. to conscript Puerto Ricans into the U.S. military.[9] The Jones Act was passed over the unanimous objection of the entire Puerto Rican House of Delegates, which was the legislature of Puerto Rico at that time.[8]

In addition to subjecting Puerto Ricans to the military draft, and sending them into World War I,[9] the Jones Act created a bicameral, popularly elected legislature in Puerto Rico (following ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1913 providing for popular election of senators), a bill of rights, and executive functions similar to those in most states. Because Puerto Rico was not a state, it did not have electoral status for U.S. presidential elections. The Act authorized popular election of the Resident Commissioner, previously appointed by the President of the U.S.

In the 1930s, leaders of the Nationalist Party split as differences arose between José Coll y Cuchí and his deputy, Pedro Albizu Campos, a Harvard-educated attorney. Coll y Cuchí left the party and Albizu Campos became president in 1931. He retained this post for the rest of his life, including terms in prison. In the 1930s, social unrest rose during the harsh conditions of the Great Depression. The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, then presided over by Albizu Campos, had some confrontations with the established government of the U.S. in the island, during which people were killed by police.

In 1938, Luis Muñoz Marín, son of Luis Muñoz Rivera and at first a member of the Liberal Party, founded the Partido Liberal, Neto, Auténtico y Completo (the "Clear, Authentic and Complete Liberal Party") in the town of Arecibo. He and his followers Felisa Rincon de Gautier and Ernesto Ramos Antonini claimed to have founded the "true" Liberal Party. His group renamed itself as the Popular Democratic Party (PPD). According to the historian Delma S. Arrigoitia, it abandoned its quest for independence and, by 1950, settled for a new political status for Puerto Rico called the Estado Libre Associado (Free Associated State), which opponents likened to continued colonialism.[10]

In the 1940 election, the PPD finished in a dead heat with Barceló's Liberal Party. In order to secure his position as Senate president, Muñoz Marin brokered an alliance with minor Puerto Rican factions, which was possible in such a multi-party system. In the elections of 1944 and 1948, the PPD gained a majority in the Senate and increasing victory margins. In addition, its candidates won almost all legislative posts and mayoral races. The Nationalist Party did not gain much electoral support.

By the late 1940s, the PPD fostered the idea of the creation of a "new" political status for the island. Under this hybrid political status as an Estado Libre Associado, or Associate Free State, the people of Puerto Rico would be allowed to elect their own governor, rather than having to accept a US appointee. In exchange, the United States would continue to control the island's monetary system, provide defense, and collect custom duties. It reserved the exclusive right to enter into treaties with foreign nations.

Under this status, the laws of Puerto Rico would continue to be subject to the approval of the Federal government of the United States.[11] The status of Estado Libre Associado displeased many advocates of Puerto Rican independence, as well as those who favored the island's being admitted as a state of the U.S.[7]

Passage

In 1948, the Senate passed a bill that restricted expressions of ideas related to the nationalist movement. The Senate at the time was controlled by the PPD and presided over by Luis Muñoz Marín.[12]

The bill, known as Law 53 and the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law), passed the legislature was signed into law on June 10, 1948, by the U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto Rico Jesús T. Piñero. It closely resembled the anti-communist Smith Law passed in the United States.[13]

The law prohibited owning or displaying a Puerto Rican flag anywhere, even in one's own home. It also became a crime to speak against the U.S. government; to speak in favor of Puerto Rican independence; to print, publish, sell or exhibit any material intended to paralyze or destroy the insular government; or to organize any society, group or assembly of people with a similar destructive intent. Anyone accused and found guilty of disobeying the law could be sentenced to ten years imprisonment, a fine of $10,000 (US), or both.[14]

Dr. Leopoldo Figueroa, a member of the Partido Estadista Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Statehood Party) and the only non-PPD member of the Puerto Rico House of Representatives, said the law was repressive and in direct violation of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees Freedom of Speech.[15] He noted that Puerto Ricans had been granted US citizenship and were covered by its constitutional guarantees.[16]

Reaction

Among those who opposed the "Gag Law" was Santos Primo Amadeo Semidey, a.k.a. "The Champion of Habeas Corpus." Amadeo Semidey was an educator, lawyer and former Senator in the Puerto Rico legislature [17] who confronted the government of Puerto Rico when the government approved and executed the laws of La Mordaza.[18] Amadeo Semidey, an expert in Constitutional Law, immediately filed a habeas corpus action with the U.S. Supreme Court which questioned the constitutionality of Law 53, and demanded the release of Enrique Ayoroa Abreu, arrested in Ponce. Amadeo Semidey and other lawyers also defended 15 members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, who were accused of breaking Gag Law 53.[19]

Revolts

| External video | |

|---|---|

On June 21, 1948, Pedro Albizu Campos, president of the Nationalist Party since 1931, gave a speech in the town of Manati where Nationalists from all over the island had gathered, in case the police attempted to arrest him. Later that month Campos visited Blanca Canales and her cousins Elio and Griselio Torresola, the Nationalist leaders of the town of Jayuya. Griselio soon moved to New York City where he met and befriended Oscar Collazo. From 1949 to 1950, the Nationalists in the island began to plan and prepare an armed revolution. The revolution was to take place in 1952, on the date the United States Congress was to approve the creation of the political status of the Commonwealth (Estado Libre Associado) for Puerto Rico. Albizu Campos called for an armed revolution because he considered the "new" status to be a colonial farce. He picked the town of Jayuya as the headquarters of the revolution because of its location. Weapons were stored in the Canales' residence.[20]

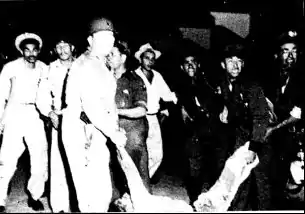

The uprisings, which became known as the "Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s," began on October 30, 1950. Albizu Campos ordered them after learning about his potential imminent arrest. Uprisings occurred in various towns, amongst them Peñuelas, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo and Ponce. Most notable were the Utuado Uprising, where the insurgents were massacred, and the Jayuya Uprising, in the town of the same name, where Nationalists attacked the police station, killing officers. The government sent in the Puerto Rican National Guard to take back control and used its planes to bomb the town.

Nationalists declared the "Free Republic of Puerto Rico" in Jayuya. Other Nationalists attempted to assassinate Governor Luis Muñoz Marín in his residence at La Fortaleza, as part of the San Juan Nationalist revolt.

By the end of the local revolts, 28 were dead - 7 police officers, 1 National Guardsman, and 16 Nationalists. There were also 49 wounded - 23 police officers, 6 National Guardsmen, 9 Nationalists and 11 non-participating bystanders.[21]

The revolts were not limited to Puerto Rico. They included a plot to assassinate United States President Harry S. Truman in Washington, D.C. On November 1, 1950, two Nationalists from New York City attacked the Blair House, where Truman was staying while renovations were being made to the White House. They did not harm him.

Truman acknowledged that it was important to settle Puerto Rico's status, and supported the plebiscite in 1952 in which voters had a chance to choose whether or not they wanted the constitution that had been drafted for the Estado Libre Associado. Nearly 82% of the voters on the island approved the new constitution.[22]

The last major attempt by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party to draw world attention to Puerto Rico's colonial situation occurred on March 1, 1954, when four nationalists: Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Irvin Flores and Andres Figueroa Cordero, attacked members of the United States House of Representatives by opening fire from the Congressional gallery. They wounded five representatives, one of them severely.[23]

Examples of suppression

Francisco Matos Paoli, Olga Viscal Garriga, Isabel Rosado and Vidal Santiago Díaz were four supporters of independence who were suppressed during the crackdown.

Francisco Matos Paoli, a poet and member of the Nationalist Party, was arrested and imprisoned under the Gag Law. For writing four Nationalist speeches and owning a Puerto Rican flag, Paoli was imprisoned for ten years.[24][25]

Olga Viscal Garriga was a student leader at the University of Puerto Rico. She was known for her skills as an orator and an active political activist. She was arrested in 1950 for participating in a demonstration that turned deadly in Old San Juan when U.S. forces opened fire and killed one of the demonstrators. Viscal Garriga was held without bail in La Princesa prison. During her trial in federal court, she was uncooperative with the U. S. Government prosecution, and refused to recognize the authority of the U.S. over Puerto Rico. She was sentenced to eight years for contempt of court (not for the initial charges regarding the demonstration), and released after serving five years.[26] Isabel Rosado was accused of participating in the revolts. Police arrested her at her job.[27] Rosado was convicted at trial and sentenced to fifteen months in jail; she was fired from her job.[27]

Vidal Santiago Díaz was Albizu Campos' barber. On October 31, he offered to serve as an intermediary if the government arrested Albizu Campos. That afternoon, while waiting alone in his barbershop Salon Boricua for an answer from the attorney general, he saw that his shop was surrounded by 15 police officers and 25 National Guardsmen. A gunfight ensued between Santiago Díaz and the police. It happened to be transmitted live via radio to the Puerto Rican public in general. The battle lasted 3 hours and came to an end after Santiago Díaz received five bullet wounds. Although Santiago Díaz had not been involved in the Nationalist revolts, he was sentenced to 17 years of prison after recovering from his wounds. He served two years before he was set free on a conditioned parole.[28]

Repeal

Law 53 (the Gag Law) or La Ley de la Mordaza as it is known in Puerto Rico, was repealed in 1957. In 1964, David M. Helfeld wrote in his article Discrimination for Political Beliefs and Associations that Law 53 was written with the explicit intent of eliminating the leaders of the Nationalist and other pro-independence movements, and to intimidate anyone who might follow them - even if their speeches were reasonable and orderly, and their activities were peaceful.[23]

Notes

- By 1948, the Puerto Rico legislature was not called the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico.

Further reading

- "War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony"; Author: Nelson Antonio Denis; Publisher: Nation Books (April 7, 2015); ISBN 978-1568585017.

See also

Articles related to the quest of Puerto Rican independence:

19th Century male leaders of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

- Ramón Emeterio Betances

- Mathias Brugman

- Francisco Ramírez Medina

- Manuel Rojas

- Segundo Ruiz Belvis

- Antonio Valero de Bernabé

19th century female leaders of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

Articles related to the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

- Cadets of the Republic

- Ponce massacre

- Río Piedras massacre

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

- Grito de Lares

- Intentona de Yauco

Articles related to Politics of Puerto Rico

References

- Pariser, Harry (1987). Explore Puerto Rico (5th ed.). Moon Publications. p. 23. ISBN 9781893643529. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

The Puerto Rican legislature under U.S. mandate passed la mordaza (the "gag law") in May 1948.

- Martinez, J.M. (2012). Terrorist Attacks on American Soil: From the Civil War Era to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-4422-0324-2. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Flores, Lisa Pierce (2010). The History of Puerto Rico. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-313-35418-2.

- "About Eugenio María de Hostos (1839–1903)". Hostos Community College. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- "José de Diego". The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War. Hispanic Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- Miles, Nelson Appleton (1896). Personal Recollections and Observations of General Nelson A. Miles.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) -

- José Trías Monge, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (Yale University Press, 1997) ISBN 0-300-07618-5

- Juan Gonzalez; Harvest of Empire, pp. 60-63; Penguin Press, 2001; ISBN 978-0-14-311928-9

- "World of 1898: The Spanish–American War", Library of Congress

- Dr. Delma S. Arrigoitia, Puerto Rico Por Encima de Todo: Vida y Obra de Antonio R. Barcelo, 1868-1938, Page 292; Publisher: Ediciones Puerto (January 2008); ISBN 978-1-934461-69-3

- Public Law 600, Art. 3, 81st Congress of the United States of America, July 3, 1950

- "La obra jurídica del Profesor David M. Helfeld (1948-2008)'; by: Dr. Carmelo Delgado Cintrón Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "Puerto Rican History". Topuertorico.org. January 13, 1941. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- "Jaime Benítez y la autonomía universitaria"; by: Mary Frances Gallart; Publisher: CreateSpace; ISBN 1-4611-3699-7; ISBN 978-1-4611-3699-6

- , Lex Juris, Ley Núm. 282, 22 December 2006

- La Gobernación de Jesús T. Piñero y la Guerra Fría

- Hernández, Rosario (July 20, 1993), R. de la C. 1310 (PDF) (in Spanish), House of Representatives of Puerto Rico, p. 2, archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011, retrieved September 1, 2010

- Puerto Rican History

- Ivonne Acosta, La Mordaza, Editorial Edile, Piedras River (1989), page 124.

- "El Grito de Lares" Archived 2008-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, New York Latino Journal, n.d.

- PROFESSOR PEDRO A. MALAVET, SEMINAR: THE U.S. TERRITORIAL POSSESSIONS; SPRING 2006; , University of Florida

- Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A Data Handbook, Volume I, p556 ISBN 9780199283576

- Helfeld, D. M. Discrimination for Political Beliefs and Associations, Revista del Colegio de Abogados de Puerto Rico; vol. 25, 1964

- "Francisco Matos Paoli".

- Francisco Matos Paoli, poeta, Proyecto Salon Hogar

- The Nationalist insurrection of 1950

- Anonymous, "Isabel Rosado Morales", Peace Host, n.d.

- The Nationalist Insurrection of 1950, Write of Fight

Further reading

- La mordaza: Puerto Rico, 1948-1957; By: Ivonne Acosta; Publisher: Editorial Edil (1987); ISBN 84-599-8469-9; ISBN 978-84-599-8469-0

- Puerto Rico Under Colonial Rule: Political Persecution And The Quest For Human Rights; By: Ramon Bosque-Perez (Editor) and Jose Javier Colon Morera (Editor); Publisher: State Univ of New York Pr; ISBN 0-7914-6417-2; ISBN 978-0-7914-6417-5

- The Puerto Rican Movement: Voices from the Diaspora (Puerto Rican Studies); By: Andres Torres; Publisher: Temple University Press; ISBN 1-56639-618-2; ISBN 978-1-56639-618-9