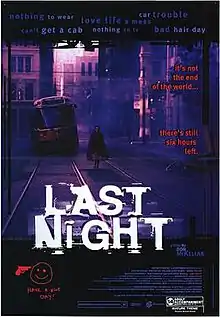

Last Night (1998 film)

Last Night is a 1998 Canadian apocalyptic black comedy-drama film directed by Don McKellar and starring McKellar, Sandra Oh and Callum Keith Rennie. It was produced as part of the French film project 2000, Seen By.... McKellar wrote the screenplay about how ordinary people would react to an unstated imminent global catastrophic event. Set in Toronto, Ontario, the film was made and released when many were concerned about the Year 2000 problem.

| Last Night | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Don McKellar |

| Written by | Don McKellar |

| Produced by | Niv Fichman Daniel Iron |

| Starring | Don McKellar Sandra Oh Tracy Wright Callum Keith Rennie Sarah Polley David Cronenberg |

| Cinematography | Douglas Koch |

| Edited by | Reginald Harkema |

| Music by | Alexina Louie Alex Pauk |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Lions Gate Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | C$2,300,000[1] |

| Box office | $591,165[2] |

The film was released to positive reviews for McKellar's direction and Oh's acting. It won awards at the Cannes and Toronto International Film Festivals, and three Genie Awards, including Best Actress for Oh.

Plot

In Toronto, a group of friends and family prepare for the end of the world, expected at midnight as the result of a calamity that is not explained, but which has been expected for several months. There has been panic and rioting after the imminent catastrophe was announced, but the chaos has since largely died down, with only sporadic murders, robberies, and incidents of vandalism as humanity accepts that Earth's demise is going to happen. On the last evening, Sandra’s car is vandalized by passersby while she scavenges leftovers in a supermarket, leaving her stranded. Meanwhile, Patrick meets with his extended family for a mock Christmas dinner celebration; Duncan, husband of Sandra, spends much of the day calling his customers to reassure them that their heating gas will be kept on until the very end; Craig is having sex with Lily as part of his plan to mark every sexual milestone he can think of before the end.

Patrick leaves the dinner prematurely to spend his final hours alone in his apartment. However, he unexpectedly meets Sandra at his front door. After Sandra begs him for help, Patrick reluctantly lets her in to use his phone to contact Duncan. Patrick then suggests Sandra steal a car, even offering to help her as she leaves his apartment. They walk out together looking for a car to steal, but ultimately, Patrick has to admit he doesn't know how to hotwire one. Meanwhile, Craig and Mrs. Carlton are having sex, and Donna turns up the music and lets herself go in the power company after Duncan had left.

Patrick meets his high school friend, Menzies, who is driving around to give out tickets to his concert with his cousin while Patrick and Sandra are trying to hitchhike. Later, Patrick, while visiting Craig in his apartment, convinces Craig to lend Sandra a car, despite his reluctance. After Sandra leaves, Craig tries to convince Patrick to enjoy sex in the final hours and discloses his omnisexual approach to addressing all of his fantasies before "the end." Craig later tells Patrick that he is not belittling Patrick but trying to inspire him to enjoy his final hours. While Patrick is leaving Craig's apartment, Craig attempts to have a homosexual affair with him, but he refuses, despite his love for Craig.

In the final hour, Duncan opens the door upon hearing a gunshot on the street only to be held hostage by Marty; in the concert that only a few people have attended, Mrs. Carlton quietly walks in while Menzies plays piano poorly on the stage. Sandra is stopped by a group of protesters who block traffic and vandalize the car she borrowed from Craig. Sandra then returns to Patrick's apartment. Using Patrick's phone, Sandra listens to Duncan's voicemail in which he assured his power company's customers that the gas will be running 'til the end. Upon realizing she will not reunite with Duncan, Sandra asks Patrick to join in her suicide pact which she had with Duncan. Patrick initially refuses, stating that he needs to know her more and to find a reason to love her in order to consider it, so they share their stories, slowly progressing into a serious topic: Patrick's lost loved one.

As midnight approaches, Craig meets with Donna and finds it difficult to believe that she is a virgin. Donna finds herself ashamed but Craig successfully turns the situation around and they have sex. While Patrick and Sandra make their final attempt to contact Duncan, it is revealed that Duncan was killed by a mob. Patrick and Sandra both sit on the roof facing each other, listening to the song "Guantanamera," each holding a loaded pistol to the other's temple. However, as the final seconds approach, both characters, overcome with emotion, lower their pistols and slowly embrace in a kiss.

Cast

- Don McKellar as Patrick Wheeler, the male protagonist who is depressed after losing his loved one due to sickness.

- Sandra Oh as Sandra, Duncan's wife, the female protagonist who is stranded in the city.

- Callum Keith Rennie as Craig Zwiller, Patrick's best friend. He spent his final hours having a sex marathon.

- Robin Gammell as Mr. Wheeler, Patrick's father.

- Roberta Maxwell as Mrs. Wheeler, Patrick's mother.

- Sarah Polley as Jennifer 'Jenny' Wheeler, Patrick's sister, Alex's girlfriend.

- Trent McMullen as Alex, Jennifer's boyfriend.

- Charmion King as Patrick's grandmother.

- Jessica Booker as Rose. She is invited to Patrick family's mock Christmas dinner celebration.

- David Cronenberg as Duncan, Sandra's husband. He works in a power company.

- Tracy Wright as Donna. She works in the same power company with Duncan. She is a virgin and has sex with Craig in the final hour.

- Geneviève Bujold as Mrs. Carlton, Patrick's and Craig's high school French teacher. She knows Craig's step mother and has sex with Craig.

- Karen Glave as Lily. She has sex with Craig knowing that Craig is only having sex with her because she is of African descent.

- Michael McMurtry as Menzies, Patrick's high school friend. He is having a concert in the final hours.

- Michael Barry as Marty. He shot Duncan with a shotgun.

- Nathalie Shats as Marty's girlfriend. She tried to stop Marty from killing Duncan.

- Arsinée Khanjian as streetcar mother. She is left stranded in a Metro with her daughter.

- Chandra Michaels as streetcar daughter. She is left stranded in a Metro with her mother.

- Jackie Burroughs as the runner. She is seen running throughout the film.

- Bob Martin as the television newscaster.

- Tom McCamus as the radio broadcaster.

Production

Development

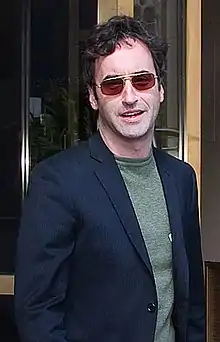

Director Don McKellar wrote the screenplay after being approached by the French producer Caroline Benjo of the firm Haut et Court[3] who asked him to join a project called "2000, Seen By..." consisting of films depicting the approaching millennium seen from the perspectives of 10 different countries.[4] McKellar fear that a story about the millennium would become dated immediately after the millennium and even questioned whether the end of the millennium has any significance.[3][5] Instead, McKellar was inspired to make his film about the end of the world, which only focus on the ordinary people's decisions, actions, and encounters that has no significant impact to the imminent catastrophic.[6] Therefore, McKellar asked his friends what they would do if they knew the end was coming, basing his screenplay on their responses.[1] His script does not explain why the world is ending because he did not view that as the point of the story.[5] However, McKellar acknowledged that the film's sun shining throughout the night "seems to suggest some major planetary alignment problems."[7] The film marked McKellar's first time directing a feature.[8]

For the C$2.2 million budget, McKellar secured the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as the main sponsor, with Haut et Court providing less than half of the budget. Afterwards, more money was raised.[9] Rhombus Media was a major sponsor.[7]

Filming

For the part of Duncan, McKellar cast Canadian director David Cronenberg, with McKellar explaining, "He takes his acting seriously," and "Cronenberg typified a certain type of person for me: a soft-spoken, articulate, careful character who may have a wild interior life- the most sane or the most insane character in the film."[10] Initially concerned about directing and acting at the same time, McKellar opted to keep the direction simple, aiming for a "fairly austere and elegant" style.[1] Shortly before shooting began, he learned a Hollywood film called Armageddon was in the works, but opted to go ahead upon hearing the stories were substantially different.[5]

Last Night was filmed on location in and near Toronto between September 15 and October 19, 1997.[1] Shooting primarily took place at the Macdonald Block and apartment buildings near The Annex.[11] Filmmakers used computers to depict an overturned streetcar, since overturning a real one would have been too expensive.[9] Cinematographer Douglas Koch used bleach bypass for sad visuals.[12]

Release

Following an advance showing for critics in Paris, Last Night premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1998, in the Directors' Fortnight section.[7] It was the first film played in Canada Perspectives at the Toronto International Film Festival. Afterwards, Lions Gate Entertainment obtained United States distribution rights.[9]

McKellar testified before the Parliament of Canada that Last Night played in theatres across Canada, before being replaced in many locations by Meet Joe Black.[13] By mid February 1999, Last Night had grossed $400,000 in Canadian theatres, a "respectable" sum, though McKellar noted the film performed better in Athens, Greece than in Toronto.[14]

Reception

Critical reception

.jpg.webp)

The film received positive reviews, with Rotten Tomatoes reporting an 84% approval rating from 49 reviews, with an average rating of 7.2/10, and the critical consensus stating, "An engrossing, poignant film, Last Night examines the end of the world through humorous and thought-provoking dialogue."[15] Roger Ebert gave the film three stars, noting fears of Y2K were prominent when he was writing in December 1999, but Last Night's apocalypse "paints a picture more bittersweet than violent." He found "moments of startling poignancy" in the last two-thirds of the film.[16] Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film "a smart, stiff-upper-lip alternative to a movie like Armageddon," and said McKellar and Sandra Oh give "intense performances," but expected more panic in the case of the apocalypse.[17] Entertainment Weekly gave the film an A−, calling it "a surreal, elegantly melancholy, and yet witty ensemble story," and Oh a "scene-stealer."[18] Peter Howell of the Toronto Star commented on the many Canadian cast members, suggesting the film is "too damn Canuck for its own good," and a riot scene would help.[19] For Maclean's, Tanya Davies declared it "a millennial coup."[20] Outside North America, critics favoured the film as "the perfect antidote" to U.S. apocalyptic films, with a U.K. critic adding "Only in Canada can you get away with a film like this."[21] Time Out called the film "a witty, perceptive movie, exceptionally well structured."[8]

In 2002, readers of Playback magazine voted Last Night the ninth greatest Canadian film of all-time.[22] In 2012, Oliver Lyttelton of IndieWire named it one of five "underseen" apocalypse films worth viewing, writing that it compared well to Armageddon and Deep Impact (1998) for "its quiet, character driven approach," and that it was likely the inspiration for Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012).[23] In 2014, Colin McNeil of Metro News wrote "Last Night is perhaps the most upbeat end-of-the-world movie you’ll ever see."[24]

In 2001, an industry poll conducted by Playback named it the third best Canadian film of the preceding 15 years.[25]

Accolades

McKellar won the "Award of the Youth" at the Cannes Film Festival and Best Canadian First Feature Film at the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival[26] for Last Night. The film also won three Genie Awards, where McKellar was effectively competing against himself as a screenwriter of both Last Night and The Red Violin.[27]

References

- Swedko, Pam (November 3, 1997). "On set with Don McKeller's Last Night". Playback. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "Last Night (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Glassman, Marc. "Last Night: In the Year of the Don". Take One: Film & Television in Canada.

- KH (2002). Allon, Yoram; Cullen, Del; Patterson, Hannah (eds.). Contemporary North American Film Directors: A Wallflower Critical Guide. London and New York: Wallflower Press. p. 367. ISBN 1903364523.

- Ostroff, Joshua (October 23, 1998). "Just the Beginning". Canoe.ca. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Weiss, Allan; Nicole, Black (2017). "'It's Over': Reflexivity In Don McKellar's Last Night". Canadian Journal of Film Studies. 26 (2): 31–45. doi:10.3138/cjfs.26.2.2017-0006. S2CID 150278853 – via JSTOR.

- Johnson, Brian D. (May 25, 1998). "French connection". Maclean's. Vol. 111, no. 21. p. 60.

- G.A. "Last Night". Time Out. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Ratzlow, Dave (November 8, 1999). "Interview: 'Last Night,' Don McKellar's Intimate Armageddon". IndieWire. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Romney, Jonathan (June 24, 1999). "Cheer up - we're all about to die". The Guardian. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Cole, Susan G.; Sumi, Glenn; Wilner, Norman; Semley, John (December 31, 2013). "Top 25 Toronto Films". Now. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- Dillon, Mark (May 3, 1999). "DOP: The versatile Doug Koch". Playback. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- McKellar, Don (April 6, 2005). "38th Parliament, 1st Session: Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- Jenish, D'Arcy (February 15, 1999). "All smiles on Genie night". Maclean's. Vol. 112, no. 7. p. 52.

- "Last Night (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (December 24, 1999). "Last Night". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Holden, Stephen (November 5, 1999). "Stranded in the City. On Doomsday to Boot". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- "Last Night". Entertainment Weekly. November 5, 1999. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Loiselle, Andre (2002). "The Radically Moderate Canadian: Don McKellar's Cinematic Persona". North of Everything: English-Canadian Cinema Since 1980. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press. p. 263. ISBN 088864390X.

- Davies, Tanya (December 28, 1998). "The year's brightest screen gems". Maclean's. Vol. 111, no. 52. p. 14.

- Melnyk, George (2004). "English Canada's Next Generation". One Hundred Years of Canadian Cinema. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. p. 217. ISBN 0802084443.

- Dillon, Mark (September 2, 2002). "Egoyan tops Canada's all-time best movies list". Playback. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Lyttelton, Oliver (June 22, 2012). "5 Underseen Apocalypse Movies To Accompany 'Seeking A Friend For The End Of The World'". IndieWire. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- McNeil, Colin (July 14, 2014). "Last Night: A very Canadian apocalypse movie". Metro News. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Posner, Michael (November 25, 2001). "Egoyan tops film poll". The Globe and Mail.

- "Last Night, No, take top prizes at fest". Hamilton Spectator, September 21, 1998.

- Kirkland, Bruce (December 8, 1998). "McKellar vs. McKellar". Canoe.ca. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Kelly, Brendan (March 7, 2000). "McKellar tops comedy noms". Variety. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Rogers Best Canadian Film Award". Toronto Film Critics Association. May 9, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "Awards". Toronto International Film Festival. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Dretzka, Gary (December 24, 1999). "Oh, Maybe Just The One". The Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2017.