Ku Klux Klan in Oregon

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) arrived in the U.S. state of Oregon in the early 1920s, during the history of the second Klan, and it quickly spread throughout the state, aided by a mostly white, Protestant population as well as by racist and anti-immigrant sentiments which were already embedded in the region.[1] The Klan succeeded in electing its members in local and state governments, which allowed it to pass legislation that furthered its agenda. Ultimately, the struggles and decline of the Klan in Oregon coincided with the struggles and decline of the Klan in other states, and its activity faded in the 1930s.[2]

Background

Racism in Oregon

Starting when it was still a territory, Oregon had several laws which prohibited both enslaved and free African Americans from living in the state. The first law, which was passed in 1843, outlawed slavery with the exception of slavery which was part of a sentence for a crime. It was amended in 1844 so a limit could be set on how much time slave owners had to move their slaves out of the state before the state would free them. However, free Blacks were also not allowed to remain in the state, the punishment for staying in the state was a lashing, but this provision was repealed before it was ever enforced. A second law which barred African Americans from migrating into Oregon was passed in 1848, but it allowed those African Americans who were already residing in the state to stay; this law was overturned in 1854.[3] When Oregon was admitted into the Union in 1859, its constitution contained an exclusionary law which prohibited Blacks from living in the state, owning property, or entering into contracts.[4] The passage of the 14th Amendment effectively overrode this law, but it was not officially repealed until 1926.[5]

Operations

Ku Klux Klan's Expansion into Oregon

The first member of the Ku Klux Klan was sworn in by Major Luther I. Powell in 1921 in Medford. During the same time, other members of the Klan were at work searching for new recruits across the state to add to their numbers and organize local chapters and klaverns.[2]

Eugene

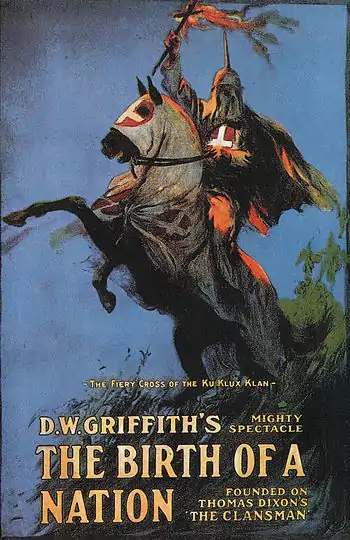

Early recruitment in Eugene was led by Powell, with help from local members and other associates of Powell, who would speak to the public alongside showings of the D. W. Griffith film The Birth of a Nation. In tandem with a religious revival in the area, they appealed to residents' concern for keeping foreign influences out as well as their desires for patriotism and morality. There were already over 80 members when a local newspaper wrote about the Klan arriving in town, and shortly thereafter the group would be formally organized under Exalted Cyclops Frederick S. Dunn, who was employed at the University of Oregon as department head of Latin studies. Members of Eugene Klan No. 3 quickly became involved in local politics, voicing not only moral stances against alcohol and prostitution, but anti-Catholic views as well, that resulted, directly and indirectly, in the ouster of several teachers and local leaders, which also coincided with the sudden resignation of Mayor Charles O. Peterson, Chief of Police Chris Christensen, and City Attorney Orla H. Foster. Additionally, many candidates endorsed by the Eugene Klan obtained local office in the fall of 1922. However, efforts to include the University of Oregon in their sphere of influence did not succeed, due to opposition from students, graduates, and faculty and administration, though this did not mean that there was no Klan presence on campus. The Klan was able to keep speakers and activities contrary to their values to a minimum; several members had business ties to campus life, a few were alumni, a few more faculty and students. Even the football graduate manager Jack Benefiel and coach, C. A. "Shy" Huntington were Klansmen. When the state legislature passed the Compulsory Education Act in 1922, the Klan's presence put Lane County among the 14 counties in the state where voters were in support of the measure.[1] In March 1924, the Klan joined forces with the local post of the American Legion (which at the time was led by Klansman George Love) to oppose Peter Vasillevich Verigin announcing that he would send around 10,000 of his Doukhobor followers from British Columbia to settle in the Willamette Valley. Ultimately, after a rally against the Doukhobor in Junction City in August, not much else would be done due to the murder of Verigin and very few Doukhobors actually moving, and their eventual return to Canada. Other than the Doukhobor incident, one of the last notable activities of Eugene Klan No. 3 was June 27, 1924, at the Lane County Fairgrounds. They held a parade through downtown, with participants and spectators from all over Oregon and from various Klan-related organizations, joined also by the city band and another local organization's band. There were fireworks and a burning cross above them on Skinner Butte, and they gathered afterward at the fairgrounds for an initiation ceremony, lit by cross covered in red lights instead of fire. Eventually, after the resignation of Fred L. Gifford from his post as Grand Dragon, in addition to national issues within the Klan, Klan No. 3 died out in the 1930s, although the exact time is not clear.[1]

Tillamook

In 1922-1925, the Ku Klux Klan saw unlikely growth in Tillamook County, on the Northern Oregon Coast. Soon after the rise of the Klan's presence in Portland, the Klan was established in Tillamook. The Klan found much success in Tillamook. The KKK also offered recognition of many native-born Protestants who were not previously accepted in their society. The KKK was originally drawn to Tillamook because of the lack of external opposition and threats. While no Klansmen were directly involved with local political occupations, becoming allies with the KKK was essential for any politician to succeed and get re-elected.[6]

Portland

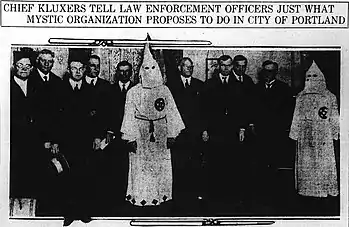

The Ku Klux Klan's development and growth across America was widely known as the "Middle-Class Movement".[7] Initial growth in Portland, was fundamentally founded on this principle. The traditions of the middle class, as well as their populist beliefs, complimented the Black exclusion laws that existed in the mid-1800s. In addition, there were anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese sentiments present because of the populations of such groups in Portland and the surrounding areas.[1] Portland was not fully made up of middle-class citizens, however, and its political activity was often anti-populist. The Klan had a very deep and complex presence in Portland, and no membership records exist of Klan members in the early 1900s. During the months of February and April 1922, over two thousand Klansmen participated in induction ceremonies; the specific number of Portland Klansmen is still unknown, but the state was estimated to contain more than 50,000 members. Members of the KKK in Portland came from a variety of backgrounds including doctors, lawyers, businessmen, clerks, and many other professions. Mount Tabor was home to many cross burnings.[7][8]

The 1924 bidding process for the replacement of the Burnside Bridge ended with a suspicious winning bid; the public would later learn that the 1924 contract was given for $500,000 more than the lowest bid. Having moved the bridge location to profit by selling their land, three Multnomah County commissioners were recalled as a result of the scandal, and a new engineering company assumed control of the project. The KKK had backed the commissioners and enabled their system of kickbacks and grafts; the ensuing "rotten bridge scandal" removed much of their clout even by 1924.[8]

Policies

Black Exclusion Laws

In the 1840s and '50s, residents of Oregon generally did not support slavery, however, they also did not want to live alongside African Americans. The first Black exclusion law was the result of the Organic Laws of Oregon, established in the Oregon Country in 1843 by the Provisional Government of Oregon. They included an article banning slavery in Oregon except for use as punishment, although the means of enforcement was left unclear. The Organic Laws were amended in 1844, reiterating the prohibition of slavery in Oregon, and forcing slave owners to remove slaves from the state. Once in effect, freed male slaves could not stay in Oregon for more than two years, and a female slave could not stay longer than three years. Any free African American who refused to leave would be subject to lashings and beatings. These punishments were prohibited in 1845.[9]

The Oregon Territorial Legislature enacted the second Black exclusion law on September 21, 1849. This law specified that "it shall not be lawful for any negro or mulatto to enter into, or reside" in Oregon. This law targeted African American seamen who could be tempted to jump overboard and swim to the coast to escape. Lawmakers were concerned that Blacks would "intermix with Indians, instilling into their minds feelings of hostility toward the white race". The second exclusion act was later rescinded in 1854.[9]

In 1857, the Oregon Constitution was ratified, and sections of Article XVIII went into effect. The article contained provisions for putting the questions of slavery and free Blacks to a vote of the people. The slavery amendment failed, but the exclusion law passed.

Notable figures

Walter M. Pierce

Walter M. Pierce was an Oregon politician from 1886 to 1942. During those years, he served in elected offices such as county recorder, state legislator, governor, and U.S. congressman. Pierce was an active participant in social movements such as populism and progressivism. Eventually, Pierce was elected to the Oregon State Senate, placing him at the forefront of these social and political reforms. His views on social reform mirrored those views which were held by members of the middle class, and at the time, the Klan's values mirrored the contradictory social and political values which were held by members of the middle class. Pierce was a supporter of radical populism and democratic populism, which led to his eventual support of and partnership with the Ku Klux Klan. After an unsuccessful run in 1918, Pierce was elected Governor of Oregon in 1922, while the political power of the Ku Klux Klan simultaneously emerged in Oregon. The Klan supported Pierce during his campaign for governor and was in close communication with Pierce as he was in office. After his retirement from political office in Oregon, Pierce would go on to be elected to Congress in 1932.[10]

References

- Lay, Shawn; Toy, Eckard (1992). "Robe and Gown: The Ku Klux Klan in Eugene, OR". The Invisible Empire in the West: Toward a New Historical Appraisal of the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 153–179. ISBN 9780252071713.

- "Ku Klux Klan". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Or. Const. Art. XVII § 4.

- "Oregon Secretary of State: Later Developments". sos.oregon.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Toll, William (1978). "Progress and Piety: The Ku Klux and Social Change in Tillamook, Oregon". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 69 (2): 75–85. ISSN 0030-8803. JSTOR 40489652.

- Johnston, Robert D. (2003). The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12600-5. JSTOR j.ctt4cgbrc.

- Chandler, J. D. (2016). Murder & Scandal in Prohibition Portland: Sex, Vice & Misdeeds in Mayor Baker's Reign. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4671-1953-5. OCLC 928581539.

- "Oregon Exclusion Law (1849)". African American National Biography. Oxford University Press. September 30, 2009. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.33707. ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1.

- Robert, McCoy (2014). "The Paradox of Oregon's Progressive Politics: The Political Career of Walter Marcus Pierce". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 115 (2): 258. doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.115.2.0258. ISSN 0030-4727.