Knowsley Hall shootings

The Knowsley Hall shootings occurred on the evening of 9 October 1952 in Knowsley Hall, Merseyside, England. Harold Winstanley, a 19-year-old trainee footman at the house, shot his employer, Lady Derby, and three colleagues. Two of those shot died: the butler, William Stallard, and the under-butler, Douglas Stuart. Winstanley fled the scene, assaulting the chef while doing so, and went to a local pub. He later took a bus into Liverpool, where he surrendered to the police. Winstanley was tried for the two murders and found guilty but insane and committed to Broadmoor Hospital.

Background

Knowsley Hall is the ancestral home of the Earls of Derby, located in Merseyside, England. In 1952, it was the residence of John Stanley, 18th Earl of Derby, and his wife, Lady Derby, Isabel Milles-Lade, daughter of Henry Milles-Lade. The couple had married in 1948 and were childless.[1] In contrast with some other aristocratic families, who had down-sized their staffs significantly to save costs in the post-war years, the Derbys continued to maintain a large staff at Knowsley, though much of the house was unused and shut off.[2][3]

Among the staff was Harold Winstanley, a 19-year-old trainee footman.[3][4] Winstanley had been born in nearby Aintree. His father had died when Winstanley was three years old, and some of his siblings and half-siblings had been taken into care. Winstanley remained with his mother and studied at the Walton Technical College, where he performed well academically.[5] Winstanley's mother was admitted to a mental institution in August 1946 and remained there until after the events of 1952.[6]

Winstanley had briefly served with the Scots Guards but was invalided on account of tuberculosis.[6] After his discharge he spent a period with the Royal Liverpool Golf Club in Wirral before joining the staff at Knowsley Hall on 15 December 1951.[4][5] Winstanley was trained in his role by the house's 40-year-old butler, William Stallard, and 29-year-old under-butler, Douglas Stuart, and was well-regarded by his colleagues.[4]

On 7 October 1952 Winstanley met a friend at Hoylake and became aware that he owned a Schmeisser MP-40 sub-machine gun.[3][nb 1] Winstanley expressed an interest in the weapon and agreed to purchase it, together with 400 rounds of ammunition, for £3 (equivalent to £92 in 2021) and a pair of trousers. Winstanley took possession of the weapon at 5:00 pm on 8 October and smuggled it into Knowsley Hall down his trousers. That evening, he filled the gun's magazines, finding he possessed only 200 rounds. He test-fired the gun in the grounds, showing it to a servant named Cooke. On 9 October, he cleaned and oiled the weapon and showed it to Anne Mitchell, a housemaid, telling her to keep it secret as he could be arrested for not having a gun licence. Later in the day, he asked Lord Derby's secretary when Lord Derby was expected home, but the secretary did not know.[4]

Shootings

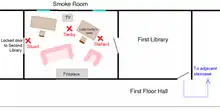

At around 8:15 pm, Lady Derby was dining alone in the first-floor Smoke Room. She was eating a dinner brought to her by the staff while seated at a table facing the corner of the room, watching a television set to her left. The door from the First Library was to her right, and the locked door to the Second Library was to her left.[4]

Winstanley entered the room from the First Library, smoking a cigarette, which was not permitted for the staff.[3] Lady Derby asked him what he wanted, stood up, and turned to face him when she noticed he was holding the MP-40. Winstanley told Lady Derby to turn around, and when she did, he shot her. Lady Derby was wounded slightly in the neck and fell forwards onto the floor, where she feigned death. She was struck by one round, which had entered the back of her neck and exited near her left ear.[4] In a statement made to the police after his arrest,[nb 2] Winstanley said he had intended to ask Lady Derby to help him dispose of the gun but had shot her after he became frightened. He said he told her to turn around as he did not want to shoot her when she was looking at him.[6]

As she was lying, Lady Derby heard Stallard enter and address Winstanley before he was shot and killed. Stallard was hit by five bullets, two of which caused fatal wounds to his head. It was established at the trial that Stallard was responding to the staff call bell activated from the Smoke Room, and the prosecution stated that only Winstanley was in a position to do so. The prosecution maintained that Winstanley had hidden in the First Library as Stallard passed through and shot him after he entered the Smoke Room.[4]

After Stallard's killing, Lady Derby also heard Stuart, who is thought to have heard the first shots and come to investigate, enter the Smoke Room and say "no".[4] He pled for his life, noting that he had a wife, to which Winstanley told him "I will look after your wife" before shooting a burst of fire. Stuart made for the locked door to the Second Library but was hit by a second burst of fire and killed.[4][6] He was struck by five bullets in the head, chest, and abdomen, and the police surgeon thought that all bar one would have been fatal alone. The police determined that 17 shots had been fired in the Smoke Room, all from a position near the door to the First Library. They thought seven had been directed at Lady Derby and five each at the butlers.[4]

After killing the two men, Winstanley moved to the first-floor hall where he met William Sullivan, Lord Derby's valet. Sullivan had heard the shots from the second floor and moved to investigate. Sullivan asked Winstanley what he was doing, but he did not answer, instead asking Mitchell and another housemaid, watching from the floor above, to come down. When the housemaids refused, Sullivan ran downstairs to the ground floor, pursued by Winstanley. On reaching the ground floor, Winstanley opened fire, wounding Sullivan in the hand with one of eleven shots. Sullivan collapsed into the entrance to the lift shaft, and Winstanley was aiming at him when other staff arrived on the scene.[4]

The housekeeper, Turley, tried to calm Winstanley down. He told her he had killed Stallard, Stuart, and Lady Derby but would not hurt the female staff. Turley made to call for the police, but Winstanley threatened to shoot her if she did. In the meantime, Lady Derby's lady's maid, Doxford, had found her and called the police from an upstairs telephone at 8:45 pm. Winstanley went to his room on the ground floor to get his coat, and the chef, Dupuy, tried to reason with him. Dupuy tried to seize the gun as they walked down a corridor to the exit. Winstanley struck him over the head with it, causing nine rounds to discharge into the wall. Dupuy was only lightly wounded in the head. Winstanley then left the house.[4]

Police search

The Liverpool City Police responded to the call and attended the house. A police surgeon treated Lady Derby and took her to the Liverpool Royal Infirmary in his car. A police search was begun. Winstanley had gone to the Coppull House, a local public house, where he drank a pint of beer.[8] He then caught a bus to Liverpool city centre where, at 11:42 pm, he called 9-9-9 from a public telephone box to hand himself in.[3][8] Liverpool City Police officers arrested him as he was in the act of leaving the phone box and pulling the gun from under his coat. On arrest, Winstanley said repeatedly, "I don't know why I did it". The MP-40 was recovered with a round in the breech and one full magazine, and 131 loose rounds were recovered from Winstanley's person. Under police questioning, Winstanley admitted to carrying out the shootings.[4]

Trial

Winstanley was charged with the murders of Stallard and Stuart. He was brought before Prescot Magistrate's Court for a committal hearing at 10:34 am on 5 November. F. D. Barry led the prosecution case, and solicitor Rex Makin the defence. Some 23 witnesses attended, including Lady Derby. The bench of three magistrates judged that there was sufficient evidence to proceed, and Winstanley's case was committed to trial at the court of assizes. Winstanley was held on remand in Walton Gaol.[4]

At the Manchester Assizes in December, Winstanley's case was prosecuted by Henry Ince Nelson QC and Robert Shenstone Nicklin and his defence led by Rose Heilbron QC and George Currie; the judge was Justice Jones. The defence did not dispute the facts of the killings and focussed instead on Winstanley's previous good character and his state of mind at the time of the shootings. Heilbron suggested that Winstanley had suffered a schizophrenic episode and could not, at that time, distinguish between right and wrong. The only witness called was Francis Brisby, the medical officer at Walton Gaol, who stated that Winstanley had schizophrenia.[5]

The case concluded on 16 December. The jury did not need to retire to consider their decision but, in a conference in the jury box, quickly returned a verdict of guilty but insane on the two counts of murder. Justice Jones ordered Winstanley to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure, and he was committed to Broadmoor Hospital.[5] No motive for the killings was ever established, with Winstanley and the other staff stating that relations with their employers were amicable.[3]

Later developments

Winstanley was later released from Broadmoor; thereafter, he would write to solicitor Rex Makin every year, updating him on his life.[9]

Legacy

Lady Derby made a full recovery from her injury.[8] The killings, together with Lord Derby's role as lord lieutenant, meaning he would need to welcome Elizabeth II to Lancashire on a visit in 1954, led to him ordering a dramatic remodelling of Knowsley Hall by architect Claud Phillimore, 4th Baron Phillimore. As around 40 house rooms were unused, and to save their heating expense and the risk of dry rot, Phillimore decided on a significant reduction in the floor plan.[3]

Between January 1953 and April 1954, an entire wing of the house and a library were demolished, reducing the footprint by a third. Significant remodelling was also carried out to the servants' quarters. This was the last time an English home was designed to accommodate a large domestic staff.[3]

Notes

- The MP-40, developed by Nazi Germany during the Second World War, was commonly known as a Schmeisser after the weapon designer Hugo Schmeisser. Schmeisser played no role in developing the MP-40, though he did help design the MP-41 variant, which saw very limited production.[7]

- At the trial, Winstanley's defence barristers applied for this statement to be discounted over the circumstances in which it had been taken, but the judge permitted the statement to be read after a short delay.[6]

References

- Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage, Baronetage, and Knightage, Privy Council, and Order of Preference. Burke's Peerage Limited. 1963. p. 706. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Lethbridge, Lucy (14 March 2013). Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth-century Britain. A&C Black. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-4088-3407-7. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Tinniswood, Adrian (7 October 2021). Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the Post-War Country House. Random House. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-1-4735-6916-4. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- "Knowsley Shootings". Liverpool Echo. 5 November 1952. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Knowsley Trial". Liverpool Echo. 16 December 1952. p. 8. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Knowsley Hall Tragedy". Cairns Post. 8 November 1952. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- Saiz, Agustin (November 2008). Deutsche Soldaten: Uniforms, Equipment & Personal Items of the German Soldier 1939–45. Casemate Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-932033-96-0. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Traynor, Luke (27 June 2017). "Rex Makin's most famous cases: The shooting of Lady Derby & the Cameo Murders". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- The Jewish Chronicle 2017.08.11, Elkan Rex Makin: Lawyer and journalist who championed the underdog against the establishment and bureaucracy