Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

The Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, which was established in 1974, preserves the historic and archaeological remnants of bands of Hidatsa, Northern Plains Indians, in North Dakota. This area was a major trading and agricultural area. Three villages were known to occupy the Knife area. In general, these three villages are known as Hidatsa villages. Broken down, the individual villages are Awatixa Xi'e (lower Hidatsa village), Awatixa and Big Hidatsa village. Awatixa Xi'e is believed to be the oldest village of the three. The Big Hidatsa village was established around 1600.

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site Archeological District | |

Reconstructed Hidatsa Indian Earthlodge | |

| |

| Location | Stanton, North Dakota |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°21′15″N 101°23′09″W |

| Area | 1,758 acres (7.11 km²) |

| Visitation | 31,079 (2005) |

| Website | Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002220[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 26, 1974 |

| Designated NHS | October 26, 1974 |

Geography

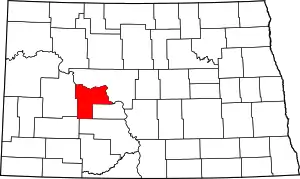

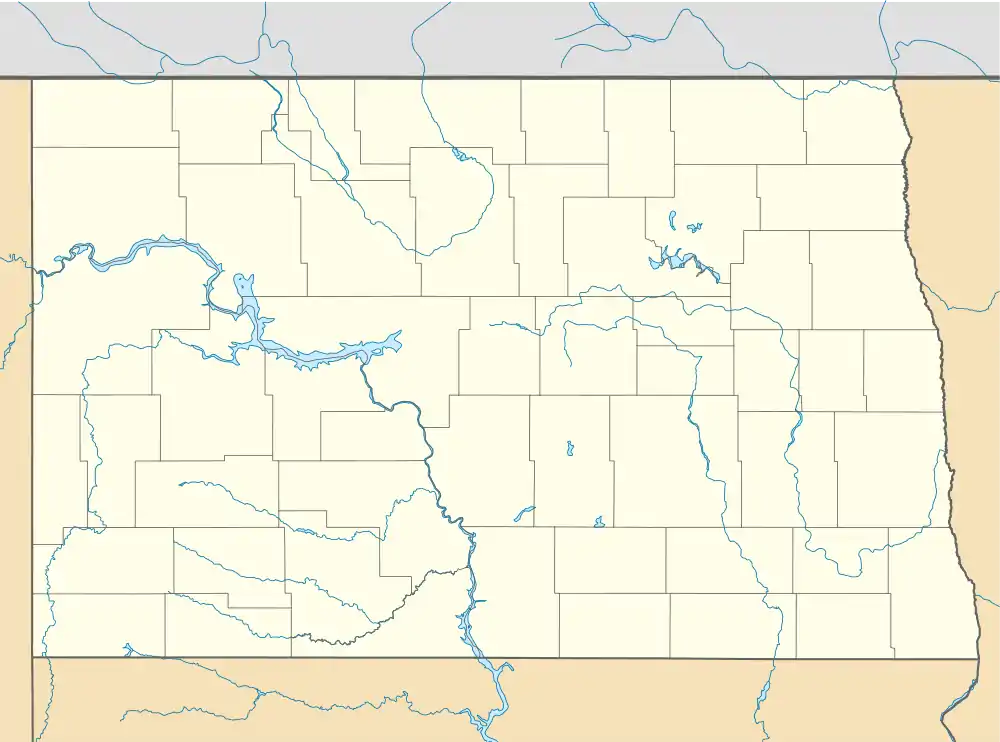

The Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site is located in central North Dakota, at the confluence of the Knife River with the Missouri River. The village is located ½ mile north of present-day Stanton, North Dakota, 1 hour north west of Bismarck, and 1 ½ hours south west of Minot, North Dakota. The Knife River is a tributary to the Missouri River. Scenic sights such as broad plains, river bluffs, and river bottom forests can all be seen along the two rivers. The national park borders both sides of the Knife River, and is made up of a forested peninsula along the length of the river.

The Missouri River is known as the "Big Muddy" due to its high sedimentation loads. The Missouri River drains approximately one-sixth of the United States and its basin encompasses 529,350 square miles (1,371,000 km2). During the pre-development period, the Missouri River represented one of North America's most diverse ecosystems.

History

Village

At the Knife River Indian Villages National Historical Site there are the visible remains of earth-lodge dwellings, cache pits, and travois trails. The remains of the earth-lodge dwellings can be seen as large circular depressions in the ground. These dwellings were as large as 40 feet in diameter and 14 feet high. They were made entirely of wood, covered by a layer of willows which was, in turn covered by a layer of dried grass. The grass layer was covered by about 4 inches of earth - hence the name. Many were once large enough to house up to 2 families. Their most valued horses were kept overnight in a coral by the door. The dwellings were constructed at ground level, but daily sweeping created a floor somewhat lower than the ground outside. The fire place was in the center and a hole in the roof allowed the smoke to get out. As the dwellings were abandoned, the walls and roof collapsed and created the visible outer circular rim.

Sakakawea (Sacagawea) was a Shoshone captive who lived in one of the villages of the Knife River. The presence of Sakakawea and her son on the Lewis and Clark Expedition was extremely crucial to the safety and guidance of the party and the success of their mission. In addition to her ability to translate for them, tribes who encountered the party believed that the presence of the young woman and child indicated they were not a threat. This is due to the fact that war parties did not allow women and children to accompany them.

The Knife River Villages served as an important major central trading and agricultural area. The Native Americans served as middlemen in a trading network that stretched from Minnesota, to the Great Plains and Gulf Coast, and the Northwest Pacific Coast. Their trading largely consisted of furs, guns, and metals such as copper, but the Hidatsa and Mandan also traded corn and other agricultural products. They raised corn, beans and squash as well as sunflowers in their extensive gardens which were managed by the women.

Smallpox epidemic

The Knife River villages thrived until 1837 when a series of smallpox outbreaks nearly wiped out the population;[2] they suffered a 50% loss in population. Gradually survivors of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara villages migrated north and developed the village of Like-a-Fishhook.

The smallpox outbreaks from 1837–1840 had a 90% death rate among the Mandan. The two Mandan villages that had been in contact with Lewis and Clark suffered the horrific effects of the virus.[3][4] The smallpox outbreak lasted from 1837–1838 and, out of 1,600 Mandan villagers, 31 survived. The smallpox epidemic was largely spread through the trading business. Despite warnings of outbreaks, Native Americans still visited trading posts and became exposed to the virus. Once the infected Mandan villages were empty, neighboring peoples raided the village for goods but suffered after carrying back the virus via blankets, horses, and household tools.

Flora and fauna

Over the hundreds of years that the Native Americans occupied this area, a very different landscape existed than what can be observed today. When occupied by the tribes, the upland areas were a mixed prairie region that contained a minimal number of trees. The floodplain forests in the river bottomlands were rich and fertile. This fertile area was cleared and used by the Native Americans in the cultivation of such crops as corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. Trees such as green ash, cottonwood, American elm, and box elder were common in the bottomlands. Other smaller trees and shrubs such as sandbar willow, red osier dogwood, and buffalo berry were also common.

In 1974, as an effort to preserve the historic value and beauty as it once appeared, the area surrounding the park was transformed back to how it originally looked when the Native Americans occupied the area. The area now contains native short grass prairies, exotic grasslands, 450 acres (1.8 km2) of hardwood forest, cultural village sites, wetland areas and sandbars.

Within some areas of the park, the forest composition has changed very little. A few prairie areas contain wheatgrass, needlegrass, grama, and big bluestem grasses, and many forbs and flowers. Native wildlife feed on plants such as choke cherry, wild plums, buffaloberry and Juneberry.

The various vegetative communities within the park are home to many species of wildlife. The surrounding forests are home to white tailed deer, coyotes, beavers, skunks, prairie pocket gophers, and thirteen-lined ground squirrels. The park is also home to a large variety of birds. Game birds found here include turkeys, pheasants, Canada geese, and mourning doves. Raptors such as owls, red-tailed hawks, bald eagles and kestrels can be spotted. Other birds surrounding the rivers that can be viewed here are white pelicans, snow geese, and great blue herons. The Missouri and the Knife Rivers are home to twenty–six known species of aquatic mollusks within the park.

Within the park limits, insect species are being collected and analyzed. Over 200 different species of invertebrates have been identified. The most common order of insects found here include Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), Hemiptera (true bugs) Homoptera (leaf hoppers), and Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants). Many of these insects are crucial to the diet of park wildlife.

As with everywhere else, the park struggles with the management of exotic invasive species. Exotic plants first appeared when Native Americans and Euro-Americans cleared the forests. Many exotic plants are introduced accidentally but a few were planted deliberately. Exotic plant species include leafy spurge, Canada thistle, and sweet clover. The park is currently conducting an inventory and monitoring program to gather information on the plant and animal species present within the park. From this information, the managers will be able to best decide how to manage and control the exotic invasive plants.

Climate

During the summer months, the temperature may reach the upper 80's with relatively low humidity and variable winds. The annual average temperature is 40 °F (4 °C). The winter months may bring below-zero temperatures. This area receives approximately 16 inches (410 mm) of precipitation a year.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site – Arikara". National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site North Dakota". National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site – Mandan". National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

1. "Climate of North Dakota." Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 3 August 2006. United States Geological Society. 19 Mar 2008 <http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/habitat/climate/figlist.htm>.

2. Eddins, O.. "Plains Indians Smallpox." Smallpox Native American Plains Indian Genocide. 19 Mar 2008 <http://www.thefurtrapper.com/indian_smallpox.htm Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine>.

3. "Knife River Indian Village – Earthlodge Interior." Lewis & Clark in North Dakota. State Historical Society of North Dakota. 18 Mar 2008 <http://www.nd.gov/hist/lewisclark/attractions_KnifeRiver.html>.

4. "Knife River Indian Villages." Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service). National Park Service. 18 Mar 2008 <http://www.nps.gov/knri/>.

5. "Knife River Indian Villages National Historical Site North Dakota." Knife River Indian Villages NHS. April 2004. National Historical Site. 19 Mar 2008 <http://www.geospectra.net/lewis_cl/knife_riv/k_river.htm#kite>.

6. Salley, Shawn. "Knife River Indian Villages National Historical Site North Dakota." Knife River Indian Villages . 18 Mar 2008 <https://web.archive.org/web/20080226071134/http://www.emporia.edu/earthsci/student/salley4/index.htm>.

7. "Stanton." Stanton. 18 Mar 2008 <http://www.stantonnd.com/>.

8. "The Missouri River Story." The River. United States Geological Society. 18 Mar 2008 <https://web.archive.org/web/20060923025250/http://infolink.cr.usgs.gov/The_River/>.