Karamanli dynasty

The Karamanli dynasty (also spelled Caramanli or Qaramanli) was an autonomous dynasty that ruled Ottoman Tripolitania from 1711 to 1835. Their territory comprised Tripoli and its surroundings in present-day Libya. At its peak, the Karamanli dynasty's influence reached Cyrenaica and Fezzan, covering most of Libya. The founder of the dynasty was Pasha Ahmed Karamanli, a descendant of the medieval Karamanids. The most well-known Karamanli ruler was Yusuf ibn Ali Karamanli Pasha who reigned from 1795 to 1832, who fought a war with the United States between 1801 and 1805. Ali II was the last of the dynasty.

| Karamanli dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Country | Tripolitania |

| Founded | 1711 |

| Founder | Ahmed Karamanli |

| Final ruler | Ali II Karamanli |

| Titles | Pasha |

| Deposition | 1832 |

History

In the early 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was losing its grip on its North African holdings, including Tripolitania. A period of civil war ensued, with no ruler able to hold office for more than a year. Ahmed Karamanli, a Janissary and popular cavalry officer, murdered the Ottoman governor of Tripolitania and seized the throne in the 1711 Karamanli coup. After persuading the Ottomans to recognize him as governor, Ahmed established himself as pasha and made his post hereditary. Though Tripolitania continued to pay nominal tribute to the Ottoman padishah, it otherwise acted as an independent kingdom.

An intelligent and able man, Ahmed greatly expanded his city's economy, particularly through the employment of corsairs on crucial Mediterranean shipping routes; nations that wished to protect their ships from the corsairs were forced to pay tribute to the pasha. On land, Ahmed expanded Tripolitania's control as far as Fezzan and Cyrenaica before his 1745 death.

Tripolitanian civil war

Ahmad's successors proved to be less capable than himself, preventing the state from ever achieving the brief golden ages of its Barbary neighbors, such as Algiers or Tunis.[1] However, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli to survive several dynastic crises without invasion.[1]

'Ali ibn Mehmed neglected the affairs of state in the 1780s and delegated most of his power to his eldest son Hasan, whom he appointed as bey. The assassination of Hasan Bey in June 1790 by 'Ali's youngest son Yusuf Karamanli triggered a war of succession between Yusuf and Hamet Karamanli ('Ali's middle son, whom he appointed as bey after Hasan's death). In 1793, Ottoman officer Ali Burghul intervened, deposed Hamet and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. However, 'Ali, Hamet and Yusuf Karamanli returned to Tripolitania in January 1794 with the aid of the bey of Tunis, expelled Burghul and reestablished Tripolitania's de facto independence under nominal Ottoman suzerainty. 'Ali formally abdicated in favour of Hamet, but Yusuf deposed Hamet within several months of the restoration, and ruled as bey of Tripoli during 1795–1832.

Barbary Wars

In 1801, Yusuf demanded a tribute of $225,000 from United States President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, confident in the ability of the new United States Navy to protect American shipping, refused the Pasha's demands, leading the Pasha to unofficially declare war, in May 1801, by chopping down the flagpole before the American consulate. Jefferson responded by ordering the US Navy into the Mediterranean, successfully blockading Tripolitania's harbors in 1803. After some initial military successes, most notably the capture of the USS Philadelphia, the pasha soon found himself threatened with invasion by American ground forces following the Battle of Derna and the reinstatement of his deposed brother, Hamet Karamanli, recruited by the American army officer William Eaton. On June 10, 1805, he signed the Treaty of Peace and Amity ending the war.

Trans-Saharan campaigns

Karamanli domination of the Fezzan was consolidated during the 18th century.[2] In the early 19th century, Yusuf expanded Karamanli influence further by sending expeditions south to consolidate control of the trans-Saharan trade routes leading to Kanem–Bornu.[2] By 1807 he was able to force all the tribes of Cyrenaica and the Fezzan, including the Awlad Sulayman, to submit to him, and brought the Fezzan under direct control.[3] Military expeditions into the central Sahara helped to secure the trade routes in 1816.[2] In 1817, Muhammad al-Mukni, the Bey of Fezzan under Karamanli authority, obtained permission from Yusuf to assist Muhammad al-Kanimi, the de facto ruler of Kanem–Bornu, in the latter's war against the neighbouring kingdom of Baghirmi.[3] From 1819 onward Yusuf started planning for a conquest of Bornu,[3] but the military expeditions that did take place seemed to be focused on profiting from the slave trade rather than on establishing administrative control over the region.[2] In 1821, Mustafa al-Ahmar (al-Mukni's successor as Bey of Fezzan) led another expedition to the Lake Chad region to assist al-Kanimi, which was successful and returned with a large number of slaves.[3][2] By 1821 Yusuf also agreed to aid the British in sending heir explorers to Bornu, but they encountered difficulties when al-Kanimi learned of Yusuf's designs on Bornu.[3] Yusuf prepared an army in the Fezzan for a major expedition against Bornu, but he needed external assistance to fund the campaign. Mustafa al-Ahmar's death in 1823 also led to delays. When his requests for a loan from the British failed in 1824, he abandoned his plans of conquering Bornu.[3]

Decline

By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania's economy began to crumble.[5] Yusuf attempted to compensate for lost revenue by encouraging the trans-Saharan slave trade, but with abolitionist sentiment on the rise in Europe and to a lesser degree the United States, this failed to salvage Tripolitania's economy. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons; though Yusuf abdicated in 1832 in favor of his son Ali II, civil war soon resulted. Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, but instead deposed and exiled Ali II, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania.[6] A descendant family with the same name still exists in modern Tripoli-Libya.

List of rulers of the Karamanli Dynasty (1711–1835)

- Ahmed I (29 July 1711 – 4 November 1745)

- Mehmed Pasha (4 November 1745 – 24 July 1754)

- Ali I Karamanli (24 July 1754 – 30 July 1793)

- Ali Pasha (30 July 1793 – 20 January 1795), also called 'Ali Burghul' – Ottoman-supported usurper

- Ahmed II (20 January – 11 June 1795), also called 'Ahmed' or 'Hamet'

- Yusuf Karamanli (11 June 1795 – 20 August 1832)

- Mehmed Karamanli (1817) (1st time, in rebellion)

- Mehmed ibn Ali (1824) (1st time, in rebellion)

- Mehmed Karamanli (1826) (2nd time, in rebellion)

- Mehmed Karamanli (July 1832) (3rd time, in rebellion)

- Mehmed ibn Ali (1835) (2nd time, in rebellion)

- Ali II Karamanli (20 August 1832 – 26 May 1835)

References

- McLachlan 1978, p. 290.

- Loimeier, Roman (2013). Muslim Societies in Africa: A Historical Anthropology. Indiana University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-253-00797-1.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M. (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0.

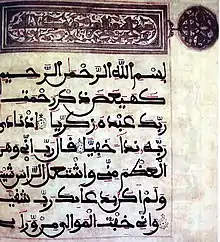

- أفا, عمر; المغراوي, محمد (2013). الخط المغربي: تاريخ وواقع وآفاق (in Arabic). مطبعة النجاح الجديدة - الدار البيضاء: منشورات وزارة الأوقاف والشؤون الإسلامية - المملكة المغربية. ISBN 978-9981-59-129-5.

- Hume 1980, p. 311.

- US Country Studies

Sources

- Dearden, Seton (1976). A Nest of Corsairs: The Fighting Karamanlis of the Barbary Coast. London: John Murray.

- Hume, L. J. (1980). "Preparations for Civil War in Tripoli in the 1820s: Ali Karamanli, Hassuna D'Ghies and Jeremy Bentham". The Journal of African History. 21 (3): 311–322.

- McLachlan, K. S. (1978). "Tripoli and Tripolitania: Conflict and Cohesion during the Period of the Barbary Corsairs (1551–1850)". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. New Series. 3 (3): 285–294.