Kaktovik numerals

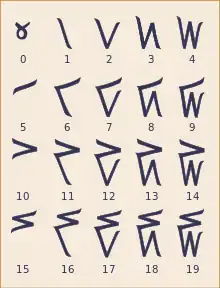

The Kaktovik numerals or Kaktovik Iñupiaq numerals[1] are a base-20 system of numerical digits created by Alaskan Iñupiat. They are visually iconic, with shapes that indicate the number being represented.

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

The Iñupiaq language has a base-20 numeral system, as do the other Eskimo–Aleut languages of Alaska and Canada (and formerly Greenland). Arabic numerals, which were designed for a base-10 system, are inadequate for Iñupiaq and other Inuit languages. To remedy this problem, students in Kaktovik, Alaska, invented a base-20 numeral notation in 1994, which has spread among the Alaskan Iñupiat and has been considered for use in Canada.

The image here shows the Kaktovik digits 0 to 19. Larger numbers are composed of these digits in a positional notation: Twenty is written as a one and a zero (![]()

![]() ), forty as a two and a zero (

), forty as a two and a zero (![]()

![]() ), four hundred as a one and two zeros (

), four hundred as a one and two zeros (![]()

![]()

![]() ), eight hundred as a two and two zeros (

), eight hundred as a two and two zeros (![]()

![]()

![]() ), and so on.

), and so on.

System

Iñupiaq, like other Inuit languages, has a base-20 counting system with a sub-base of 5 (a quinary-vigesimal system). That is, quantities are counted in scores (as in Welsh, and in some Danish such as halvtreds 'fifty', and French, such as quatre-vingts 'eighty'), with intermediate numerals for 5, 10, and 15. Thus 78 is identified as three score fifteen-three.[2]

The twenty digits are:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

The Kaktovik digits graphically reflect the lexical structure of the Iñupiaq numbering system. For example, the number seven is called tallimat malġuk in Iñupiaq ('five-two'), and the Kaktovik digit for seven is a top stroke (five) connected to two bottom strokes (two): ![]() . Similarly, twelve and seventeen are called qulit malġuk ('ten-two') and akimiaq malġuk ('fifteen-two'), and the Kaktovik digits are respectively two and three top strokes (ten and fifteen) with two bottom strokes:

. Similarly, twelve and seventeen are called qulit malġuk ('ten-two') and akimiaq malġuk ('fifteen-two'), and the Kaktovik digits are respectively two and three top strokes (ten and fifteen) with two bottom strokes: ![]() ,

, ![]() .[3]

.[3]

Values

In the following table are the decimal values of the Kaktovik digits up to three places to the left and to the right of the units' place.[3]

| n | n×203 | n×202 | n×201 | n×200 | n×20−1 | n×20−2 | n×20−3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,000 | 400 | 20 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.0025 | 0.000125 |

| 2 | 16,000 | 800 | 40 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.00025 |

| 3 | 24,000 | 1,200 | 60 | 3 | 0.15 | 0.0075 | 0.000375 |

| 4 | 32,000 | 1,600 | 80 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.0005 |

| 5 | 40,000 | 2,000 | 100 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.0125 | 0.000625 |

| 6 | 48,000 | 2,400 | 120 | 6 | 0.3 | 0.015 | 0.00075 |

| 7 | 56,000 | 2,800 | 140 | 7 | 0.35 | 0.0175 | 0.000875 |

| 8 | 64,000 | 3,200 | 160 | 8 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.001 |

| 9 | 72,000 | 3,600 | 180 | 9 | 0.45 | 0.0225 | 0.001125 |

| 10 | 80,000 | 4,000 | 200 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.025 | 0.00125 |

| 11 | 88,000 | 4,400 | 220 | 11 | 0.55 | 0.0275 | 0.001375 |

| 12 | 96,000 | 4,800 | 240 | 12 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.0015 |

| 13 | 104,000 | 5,200 | 260 | 13 | 0.65 | 0.0325 | 0.001625 |

| 14 | 112,000 | 5,600 | 280 | 14 | 0.7 | 0.035 | 0.00175 |

| 15 | 120,000 | 6,000 | 300 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.0375 | 0.001875 |

| 16 | 128,000 | 6,400 | 320 | 16 | 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| 17 | 136,000 | 6,800 | 340 | 17 | 0.85 | 0.0425 | 0.002125 |

| 18 | 144,000 | 7,200 | 360 | 18 | 0.9 | 0.045 | 0.00225 |

| 19 | 152,000 | 7,600 | 380 | 19 | 0.95 | 0.0475 | 0.002375 |

Origin

In the early 1990s, during a math enrichment activity at Harold Kaveolook school in Kaktovik, Alaska,[4] students noted that their language used a base-20 system and found that, when they tried to write numbers or do arithmetic with Arabic numerals, they did not have enough symbols to represent the Iñupiaq numbers.[5] The students first addressed this lack by creating ten extra symbols, but found these were difficult to remember. The middle school in the small town had nine students, so it was possible for the entire class to work together to create a base-20 notation. Their teacher, William Bartley, guided them.[5]

After brainstorming, the students came up with several qualities that an ideal system would have:

- Visual simplicity: The symbols should be "easy to remember"

- Iconicity: There should be a "clear relationship between the symbols and their meanings"

- Efficiency: It should be "easy to write" the symbols, and they should be able to be "written quickly" without lifting the pencil from the paper

- Distinctiveness: They should "look very different from Arabic numerals," so there would not be any confusion between notation in the two systems

- Aesthetics: They should be pleasing to look at[5]

In base-20 positional notation, the number twenty is written with the digit for 1 followed by the digit for 0. The Iñupiaq language does not have a word for zero, and the students decided that the Kaktovik digit 0 should look like crossed arms, meaning that nothing was being counted.[5]

When the middle-school pupils began to teach their new system to younger students in the school, the younger students tended to squeeze the numbers down to fit inside the same-sized block. In this way, they created an iconic notation with the sub-base of 5 forming the upper part of the digit, and the remainder forming the lower part. This proved visually helpful in doing arithmetic.[5]

Computation

Abacus

The students built base-20 abacuses in the school workshop.[4][5] These were initially intended to help the conversion from decimal to base-20 and vice versa, but the students found their design lent itself quite naturally to arithmetic in base-20. The upper section of their abacus had three beads in each column for the values of the sub-base of 5, and the lower section had four beads in each column for the remaining units.[5]

Arithmetic

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

An advantage the students discovered of their new system was that arithmetic was easier than with the Arabic numerals.[5] Adding two digits together would look like their sum. For example,

- 2 + 2 = 4

is

+

+  =

=

It was even easier for subtraction: one could simply look at the number and remove the appropriate number of strokes to get the answer.[5] For example,

- 4 − 1 = 3

is

−

−  =

=

Another advantage came in doing long division. The visual aspects and the sub-base of five made long division with large dividends almost as easy as short division, as it didn't require writing in subtables for multiplying and subtracting the intermediate steps.[4] The students could keep track of the strokes of the intermediate steps with colored pencils in an elaborated system of chunking.[5]

A simplified multiplication table can be made by first finding the products of each base digit, then the products of the bases and the sub-bases, and finally the product of each sub-base:

| × | 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

× | 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

× | 5 |

10 |

15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

5 |

5 |

|||||||||||||

| 2 |

10 |

10 |

|||||||||||||

| 3 |

15 |

15 |

|||||||||||||

| 4 |

These tables are functionally complete for multiplication operations using Kaktovik numerals, but for factors with both bases and sub-bases it is necessary to first disassociate them:

6 * 3 = 18

is

![]() *

* ![]() = (

= (![]() *

* ![]() ) + (

) + (![]() *

* ![]() ) =

) = ![]()

In the above example the factor ![]() (6) is not found in the table, but its components,

(6) is not found in the table, but its components, ![]() (1) and

(1) and ![]() (5), are.

(5), are.

Legacy

The Kaktovik numerals have gained wide use among Alaskan Iñupiat. They have been introduced into language-immersion programs and have helped revive base-20 counting, which had been falling into disuse among the Iñupiat due to the prevalence of the base-10 system in English-medium schools.[4][5]

When the Kaktovik middle school students who invented the system were graduated to the high school in Barrow, Alaska (now renamed Utqiaġvik), in 1995, they took their invention with them. They were permitted to teach it to students at the local middle school, and the local community Iḷisaġvik College added an Inuit mathematics course to its catalog.[5]

In 1996, the Commission on Inuit History Language and Culture officially adopted the numerals,[5] and in 1998 the Inuit Circumpolar Council in Canada recommended the development and use of the Kaktovik numerals in that country.[6]

Significance

Scores on the California Achievement Test in mathematics for the Kaktovik middle school improved dramatically in 1997 compared to previous years. Before the introduction of the new numerals, the average score had been in the 20th percentile; after their introduction, scores rose to above the national average. It is theorized that being able to work in both base-10 and base-20 might have comparable advantages to those bilingual students have from engaging in two ways of thinking about the world.[5]

The development of an indigenous numeral system helps to demonstrate to Alaskan-native students that math is embedded in their culture and language rather than being imparted by western culture. This is a shift from a previously commonly held view that mathematics was merely a necessity to get into a college or university. Non-native students can see a practical example of a different world view, a part of ethnomathematics.[7]

In Unicode

The Kaktovik numerals were added to the Unicode Standard in September, 2022, with the release of version 15.0. A font is available in the external links.

| Kaktovik Numerals[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1D2Cx | 𝋀 | 𝋁 | 𝋂 | 𝋃 | 𝋄 | 𝋅 | 𝋆 | 𝋇 | 𝋈 | 𝋉 | 𝋊 | 𝋋 | 𝋌 | 𝋍 | 𝋎 | 𝋏 |

| U+1D2Dx | 𝋐 | 𝋑 | 𝋒 | 𝋓 | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1D2Cx | ||||||||||||||||

| U+1D2Dx |

See also

- Maya numerals, a quinary-vigesimal system from another American culture

References

- Edna Ahgeak MacLean (2012) Iñupiatun Uqaluit Taniktun Sivunniuġutiŋit: North Slope Iñupiaq to English Dictionary

- MacLean (2014) Iñupiatun Uqaluit Taniktun Sivuninit / Iñupiaq to English Dictionary, p. 840 ff.

- MacLean (2014) Iñupiatun Uqaluit Taniktun Sivuninit / Iñupiaq to English Dictionary, p. 832

- Bartley, Wm. Clark (January–February 1997). "Making the Old Way Count" (PDF). Sharing Our Pathways. 2 (1): 12–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- Bartley, William Clark (2002). "Counting on tradition: Iñupiaq numbers in the school setting". In Hankes, Judith Elaine; Fast, Gerald R. (eds.). Perspectives on Indigenous People of North America. Changing the Faces of Mathematics. Reston, Virginia: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. pp. 225–236. ISBN 978-0873535069.

- "Regarding Kaktovik Numerals. Resolution 89-09. Inuit Circumpolar Council. 1998". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Engblom-Bradley, Claudette (2009). "Seeing mathematics with Indian eyes". In Williams, Maria Sháa Tláa (ed.). The Alaska Native Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 237–245. ISBN 9780822390831. See in particular p. 244.

Further reading

- Tillinghast-Raby, Amory (April 10, 2023). "A Number System Invented by Inuit Schoolchildren Will Make Its Silicon Valley Debut". Scientific American. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

External links

- free Kaktovik font, based on Bartley (1997)

- Kaktovik–Arabic converter, using either images or Unicode

- Grunewald, Edgar (December 30, 2019). "Why These Are The Best Numbers!". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2019. The video demonstrates how long division is easier with visually intuitive digits like the Kaktovik ones; the illustrated problems were chosen to work out easily, as the problems in a child's introduction to arithmetic would be.

- Silva, Eduardo Marín; Miller, Kirk; Strand, Catherine (April 29, 2021). "Unicode request for Kaktovik numerals (L2/21-058R)" (PDF). Unicode Technical Committee Document Registry. Retrieved April 30, 2021.