Journey Through the Impossible

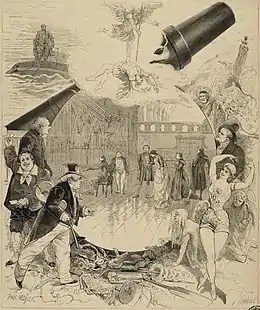

Journey Through the Impossible (French: Voyage à travers l'impossible) is an 1882 fantasy play written by Jules Verne, with the collaboration of Adolphe d'Ennery. A stage spectacular in the féerie tradition, the play follows the adventures of a young man who, with the help of a magic potion and a varied assortment of friends and advisers, makes impossible voyages to the center of the Earth, the bottom of the sea, and a distant planet. The play is deeply influenced by Verne's own Voyages Extraordinaires series and includes characters and themes from some of his most famous novels, including Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and From the Earth to the Moon.

The play opened in Paris at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin on 25 November 1882, and achieved a financially successful run of 97 performances. Contemporary critics gave the play mixed reviews; in general, the spectacular staging and the use of ideas from Verne's books were highly praised, while the symbolism and moral themes in the script were criticized and attributed to the collaboration of d'Ennery. The play was not published during Verne's lifetime and was presumed lost until 1978, when a single handwritten copy of the script was discovered; the text has since been published in both French and English. Recent scholars have discussed the play's exploration of the fantasy genre and of initiation myths, its use of characters and concepts from Verne's novels, and of the ambiguous treatment of scientific ambition in the play, marking a transition from optimism to pessimism in Verne's treatment of scientific themes.

Plot

About twenty years before the play begins, the Arctic explorer Captain John Hatteras became the first man to reach the North Pole, but went mad in the attempt (as described in Verne's novel The Adventures of Captain Hatteras). Upon his return to England, where he spent the rest of his life in a mental hospital, his young son Georges was confided to the care of the aristocrat Madame de Traventhal, of Castle Andernak in Denmark.

At the start of the play, Georges is living with Madame de Traventhal and her granddaughter Eva, to whom he is engaged. He has never learned the identity of his father, but he dreams obsessively of travel and adventure, and wishes to follow in the footsteps of great explorers: Otto Lidenbrock (from Journey to the Center of the Earth), Captain Nemo (from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea), Michel Ardan (from From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon), and especially Captain Hatteras. Madame de Traventhal, in the hope of curing him of his obsession, sends for a physician newly arrived in the country, a certain Doctor Ox (from the short story "Dr. Ox's Experiment"). Ox enters and is welcomed into the castle, although he does not seem to get along well with Master Volsius, a local church organist and friend of the de Traventhals.

Doctor Ox, catching him alone, reveals Georges's true parentage, and persuades him to drink a magic potion that allows him to go beyond the limits of the probable and journey through the impossible. Eva, realizing what has happened, takes the potion and drinks some as well, so as not to desert Georges. A family friend, the dancing master Tartelet (from The School for Robinsons), is seduced by the opportunity to travel and drinks his own share of the potion before anyone can stop him. Ox sets off with all three travelers, while Volsius makes secret plans to come along and protect Georges from Ox's influence. Along the way, another Dane, Axel Valdemar, also gets mixed up into the journey and becomes a friend of Tartelet.

During the voyages, Volsius reappears in the guise of Georges's heroes: Otto Lidenbrock at the center of the Earth, Captain Nemo on a journey on the Nautilus to Atlantis, and Michel Ardan on a cannon-propelled trip to a distant planet, Altor. Ox and Volsius are in constant conflict throughout, with the former urging Georges toward hubris and the latter seeking to protect Georges from the influence. Ox appears to have won at the climax of the play, when Georges—attempting to work for the benefit of Altor, where overconsumption has deprived the planet of soil and other natural resources—leads a massive technological project to save the planet from burning by redirecting its water channels. The project backfires, and the planet explodes.

Through the magical intervention of Ox and Volsius, the travelers are brought back to Castle Andernak, where Georges is on the brink of death. Volsius persuades Ox to work together with him, resolving the tension between them by revealing that the world needs both symbolic figures—scientific knowledge and spiritual compassion—to work in harmony. Together, they bring Georges back to life and health. He renounces his obsessions and promises to live happily ever after with Eva.

Themes

The play's most prominent thematic inspiration is Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires series, which it freely invokes and refers to; in addition to plot elements taken from Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, From the Earth to the Moon, and Around the Moon, the character of Doctor Ox reappears from the short story "Dr. Ox's Experiment," Mr. Tartelet is derived from a character in The School for Robinsons, and the hero Georges is described as the son of Captain Hatteras from The Adventures of Captain Hatteras.[1] At the same time, the plot of the play sets it distinctly apart from the rest of Verne's work. While his novels are based on meticulously researched facts and plausible conjectures, and often end with an ultimate goal remaining unattainable, the play explores the potential of letting a character go beyond all plausible limits and carry out adventures in a domain of pure fantasy.[2]

Like many of Verne's novels, the play is deeply imbued with themes of initiation, echoing the traditional mythic pattern of a young hero coming of age and reaching maturity through a dangerous and transformative journey.[3] In Journey Through the Impossible, the young Georges, initially trapped by obsessions similar to those that drove his father mad, resolves his inner torments during a harrowing series of experiences in which Ox and Volsius compete as substitute father-figures.[4] Both father-figures are highly symbolic: Ox is a sinister tempter representing knowledge and science, balancing the Guardian Angel Volsius.[5]

The play also features an ambiguous and multifaceted portrayal of scientific knowledge, celebrating it for its humanistic achievements and discoveries, but also warning that it can do immense harm when in the hands of the unethical or overambitious.[6] Given these themes, the play is likely Verne's most purely science-fictional work.[7] Structurally, the play evokes the three-part design of Jacques Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann,[8] in which the hero must choose between love and art.[5] In Journey Through the Impossible, however, the choice is between positive ideals—love, goodness, happiness—and the unbounded scientific ambitions of the sinister Doctor Ox.[5]

The use of scientific themes mark the play's position at a major turning-point in Verne's ideology.[5] In Verne's earlier works, knowledgeable heroes aim to use their skills to change the world for the better; in his later novels, by contrast, scientists and engineers often apply their knowledge toward morally reprehensible projects. The play, by exploring science in both positive and negative lights, shows Verne in transition between the two points of view.[6]

Production

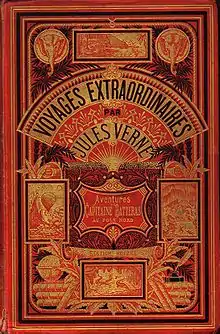

Since 1863, Verne had been under contract with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, who published each of his novels, beginning with Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and continuing through the rest of his books to form the novel sequence Hetzel called the Voyages Extraordinaires. The arrangement gave Verne prominence as a novelist and a certain amount of financial stability, but under the terms of the contract Verne's profits barely earned him a living wage.[9] Verne's fortunes changed markedly in 1874, when the stage adaptation of his novel Around the World in Eighty Days was a smash hit, running for 415 performances in its original production and quickly making Verne wealthy as well as famous as a playwright. Adapted with the collaboration of the showman d'Ennery, the play invented and codified the pièce de grand spectacle, an extravagant theatrical genre that became intensely popular in Paris throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century.[10] Verne and d'Ennery went on to adapt two other Verne novels, The Children of Captain Grant and Michael Strogoff, as similarly spectacular plays.[10]

Verne began playing with the idea of bringing a mixed selection of Voyages Extraordinaires characters together on a new adventure in early 1875, when he considered writing a novel in which Samuel Fergusson from Five Weeks in a Balloon, Pierre Aronnax from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Phileas Fogg from Around the World in Eighty Days, Dr. Clawbonny from The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, and other characters would go around the world together in a heavier-than-air flying machine. Another novel featuring a similar trip around the world in a flying machine, Alphonse Brown's La Conquête de l'air, was published later that year, causing Verne to put the idea on hold.[11] The idea, in highly modified form, finally reemerged five years later as Journey Through the Impossible.[12]

Verne went to d'Ennery with the idea in February 1880, and they collaborated in Antibes for several weeks on two projects simultaneously: the dramatization of Michael Strogoff and the new play.[12] Journey Through the Impossible was the only one of their collaborations not based directly on a pre-existing Verne novel.[13] Modern scholarship has not been successful in determining how much of the play each of the collaborators wrote, but the Verne scholar Robert Pourvoyeur has suggested that the play is clearly founded on Verne's ideas and therefore can be treated as being mostly the work of Verne.[14]

According to contemporary rumors, Verne and d'Ennery came to difficulties over the treatment of science in the play, with d'Ennery wanting to condemn scientific research and Verne advocating a more science-friendly and hopeful approach. Verne reportedly cut some especially negative lines out of the script, and protested when d'Ennery had them reinserted for the production.[15] Journey Through the Impossible would be their last collaboration.[10] The play is also Verne's only contribution to the féerie genre.[16]

Joseph-François Dailly, the first actor to play the role of Passepartout in Around the World in Eighty Days, was cast as Valdemar; another cast member of Around the World, Augustin-Guillemet Alexandre, played opposite him as Tartelet. Paul-Félix Taillade, who had appeared in The Children of Captain Grant, was cast as Doctor Ox, and Marie Daubrun, a well-known féerie actress who was also the mistress and muse of Charles Baudelaire, played Eva. The production was directed by Paul Clèves (born Paul Collin), the director of the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin from 1879 to 1883.[17] Oscar de Lagoanère, a prolific composer and music director, wrote the music for the play.[14]

Reception

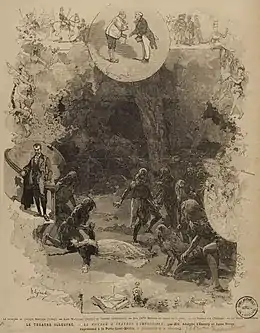

The play, advertised as une pièce fantastique en trois actes,[1] premiered in Paris at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin on 25 November 1882.[18] As with the previous Verne–d'Ennery collaborations, Journey Through the Impossible had a gala opening night.[13] The play was a pronounced box-office success;[14][19] however, critical reception was mixed.[13] In the 1882 edition of Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, Édouard Noël and Edmond Stoullig criticized the play for including "Catholico-reactionary mysticism which seeks to elicit tears of holy water from the audience;" Noël and Stoullig suspected that d'Ennery was to blame for the mystical overtones.[13] In Le Temps, Francisque Sarcey panned the play with a brief notice, claiming that all the other plays running that week were "far more interesting and entertaining." He noted the innovative Verne-d'Ennery idea of using the human characters of Volsius and Ox to represent good and evil in the fantasy, rather than resorting to the typical "Good Fairy" and "Bad Fairy" characters in such plays, but added that he "didn't quite see what we've gained by the substitution."[13]

The Parisian critic Arnold Mortier, in a long review of the play, described it as "beautiful" and "elegant", and highly praised Dailly's performance as Valdemar, but believed the staging lacked originality: "a great deal of money went into this production, but very few ideas." Like Sarcey, he commented with some asperity on the metaphorical use of Volsius and Ox as symbols of Good and Evil, rather than attractive young women playing Good and Bad Fairies: "Is it not time, perhaps, to return to that practice?"[20] An anonymous reviewer for The New York Times said of the play: "I have never seen anything more idiotically incoherent, or of which the dialogue is more pretentious," but predicted that it would be a success because of its spectacular production values.[21] Henri de Bornier gave the play a brief but highly positive notice in La Nouvelle revue, highlighting the elegance of the decor and commenting Verne and d'Ennery had done humankind a "true service" by exploring impossible domains on the stage.[22]

Charles Monselet, in Le Monde Illustré, praised Taillade and the "curious" nature of the voyages, but found the play as a whole tiresome.[23] On the other hand, two other major illustrated journals, L'Illustration and L'Univers Illustré, greeted the play with wholly positive reviews, particularly lauding the spectacular staging.[24][25] Auguste Vitu gave the play a largely positive review, praising the actors, the decor, and the use of Verne's ideas, but expressed doubts about the wisdom of combining so many disparate styles—dramatic realism, scientific fiction, and pure fantasy—in one production.[26] Anonymous reviewers in the Revue politique et littéraire and the Revue Britannique, as well as Victor Fournel in Le Correspondant and Arthur Heulhard in the Chronique de l'Art, all wrote similarly mixed reviews, speaking highly of the actors and of Verne's characters and concepts but saying that d'Ennery's dramatizations and revisions were clumsy.[27][28][29][30] In his 1910 history of the féerie, Paul Ginisty hailed Journey Through the Impossible for introducing a "scientific element" to the genre and for bringing characters from Verne's books to the stage, but sharply criticized d'Ennery for putting "furiously outdated" sentiments in the mouth of the character Volsius.[15]

Journey Through the Impossible ran for 97 performances,[18] and contributed to the ongoing fame of both Verne and d'Ennery.[14] In 1904, the pioneering director Georges Méliès freely adapted the play into a film, The Impossible Voyage.[19]

Rediscovery

The play was not published in Verne's lifetime and was presumed lost until 1978, when a handwritten copy was discovered in the Archives of the Censorship Office of the Third Republic.[18] The text was published in France by Jean-Jacques Pauvert in 1981.[18] An English translation by Edward Baxter was commissioned by the North American Jules Verne Society and published in 2003 by Prometheus Books.[31] The first production of the play after its rediscovery occurred in 2005, in a small-scale performance at the Histrio Theatre in Washington, DC.[32]

Since its rediscovery, the play has been studied and analyzed by scholars interested in its place in Verne's oeuvre, though it remains relatively little-known among his works.[32] The American Verne scholar Arthur B. Evans has called it "delightful," saying it "shows [Verne] at his most whimsically science-fictional."[31] The Swiss-American Verne scholar Jean-Michel Margot has described it as "one of the most intriguing, surprising, and important later works by Jules Verne."[7]

Notes

References

- Theodoropoulou 2009, p. 20

- Margot 2005, pp. 154–5

- Theodoropoulou 2009, pp. 41–42

- Theodoropoulou 2009, pp. 92, 47

- Margot 2005, p. 155

- Margot, Jean-Michel (2003), "Introduction", in Verne, Jules (ed.), Journey Through the Impossible, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, pp. 11–19

- Margot 2005, p. 156

- Theodoropoulou 2009, p. 11

- Margot 2005, p. 153

- Margot 2005, p. 154

- Verne, Jules; Hetzel, Pierre-Jules; Dumas, Olivier; Gondolo della Riva, Piero; Dehs, Volker (1999), Correspondance inédite de Jules Verne et de Pierre-Jules Hetzel (1863-1886), vol. II, Geneva: Slatkine, p. 52

- Butcher, William (2008), Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography (revised ed.), Hong Kong: Acadien, p. 289

- Lottmann, Herbert R. (1996), Jules Verne: an exploratory biography, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 233–234

- Theodoropoulou 2009, p. 5

- Ginisty, Paul (1910), La Féerie, Paris: Louis-Michaud, pp. 214–215, retrieved 10 March 2014

- Theodoropoulou 2009, p. 9

- Margot, Jean-Michel (2003), "Notes", in Verne, Jules (ed.), Journey Through the Impossible, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, pp. 161–180

- Margot 2005, p. 161

- Unwin, Timothy A. (2005), Jules Verne: Journeys in Writing, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p. 98, ISBN 9780853234685

- Mortier, Arnold (2003), "Evenings in Paris in 1882: Journey Through the Impossible", in Verne, Jules (ed.), Journey Through the Impossible, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, pp. 147–153

- "A Jules Verne Piece", The New York Times, 19 December 1889, reprinted in Verne, Jules (2003), Journey Through the Impossible, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, pp. 155–160

- de Bornier, Henri (15 December 1882), "Revue du Théâtre: Drame et comédie", La Nouvelle revue, 19 (4): 926, retrieved 25 November 2014

- Monselet, Charles (2 December 1882), "Théâtre", Le Monde Illustré, no. 1340. Reproduced online at the German Jules Verne Club's European Jules-Verne-Portal Archived 2015-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 November 2014.

- Sayigny (2 December 1882), "Le Voyage à travers l'impossible", L'Illustration, vol. LXXX, no. 2075. Reproduced online at the German Jules Verne Club's European Jules-Verne-Portal Archived 2015-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 November 2014.

- Damon (2 December 1882), "Voyage à travers l'impossible", L'Univers Illustré. Reproduced online at the German Jules Verne Club's European Jules-Verne-Portal Archived 2015-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 November 2014.

- Vitu, Auguste (1885), "Voyage à travers l'impossible", Les milles et une nuits du théâtre, vol. 8, Paris: Ollendorff, pp. 498–504, retrieved 25 November 2014

- "Notes et impressions", Revue politique et littéraire, 3 (23): 732, 2 December 1882, retrieved 25 November 2014

- "Chronique et bulletin bibliographique", Revue Britannique, 6: 559, December 1882, retrieved 25 November 2014

- Fournel, Victor (25 December 1882), "Les Œuvres et les Hommes", Le Correspondant: 1183, retrieved 25 November 2014

- Heulhard, Arthur (7 December 1882), "Art dramatique", Chronique de l'Art (49): 581–582, retrieved 25 November 2014

- Evans, Arthur B (November 2004), "Books in Review: Verne on Stage", Science Fiction Studies, 3, XXXI (94): 479–80, retrieved 10 February 2013

- Theodoropoulou 2009, p. 6

Citations

- Margot, Jean-Michel (March 2005), "Jules Verne, playwright", Science Fiction Studies, 1, XXXII (95): 150–162, retrieved 11 February 2013

- Theodoropoulou, Athanasia (2009), Stories of initiation for the modern age: explorations of textual and theatrical fantasy in Jules Verne's Voyage à travers l'impossible and Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials (PhD thesis), University of Edinburgh, hdl:1842/4294, retrieved 8 September 2014

External links

- Music inspired by the play from the North American Jules Verne Society

- A scenic model from the original production at the Bibliothèque nationale de France