José Sarria

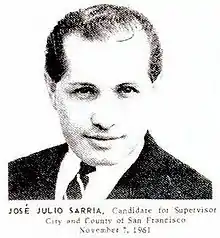

José Julio Sarria (December 13, 1922 – August 19, 2013),[1][2] also known as The Grand Mere, Absolute Empress I de San Francisco, and the Widow Norton, was an American political activist from San Francisco, California, who, in 1961, became the first openly gay candidate for public office in the United States. He is also remembered for performing as a drag queen at the Black Cat Bar and as the founder of the Imperial Court System.

José Sarria | |

|---|---|

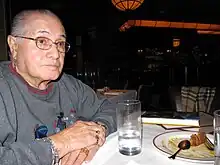

Sarria dines in Kenmore Square, 2010 | |

| Born | José Julio Sarria December 13, 1922[1] San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 19, 2013 (aged 90) |

| Other names | The Nightingale of Montgomery Street Empress José I, The Widow Norton |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | First openly gay candidate for public office in the United States |

Family history

José Sarria was born in San Francisco, California, to Maria Dolores Maldonado and Julio Sarria. His family was of Spanish and Colombian origin.[3] His mother Maria was born in Bogotá to an upper class and politically active family.[4] During the events of the Thousand Days War and following her mother's death, Maria sought out the protection of her mother's friend, General Rafael Uribe Uribe, to escape Colombia.[5] The general located Maria's surviving uncle, who took her to the American consulate. There she was made a ward of the United States and relocated to Panama.[6] "My mother got to Panama with directions to the home of a family called Kopp. He was the chairman of the big German beer company there",[7] said Sarria. "She went to work for the Kopps. ... My mother was the upstairs maid and took care of the children."[7] In 1919, she relocated to Guatemala City but remained there for just six months and, in 1920, sailed to San Francisco.[8] As Sarria reported it, "Now on the boat is where my mother met my father, Julio Sarria. He came from a large and very wealthy family, very well known. ... His grandparents came from Spain."[9]

Maria initially worked for the woman who sponsored her passage to the United States[10] and then took a job as a maid with a family named Jost. Julio was the maitre d' at the Palace Hotel.[11] Julio courted Maria until she realized she was pregnant. Their son José was born on December 12. His birth certificate reads 1923 but Sarria believed he was born in 1922.[12][13] Julio and Maria never married.

Early life

Sarria's mother continued to work for the Jost family, but it became increasingly difficult for her to fulfill her job responsibilities and care for an infant.[14] Maria made arrangements for him to be raised by another couple, Jesserina and Charles Millen.[15] Jesserina had recently lost her youngest child to diphtheria and suffered severe depression. Her doctor suggested she take in another child to raise and, after meeting with her, Maria agreed to let her raise José. José came to consider the Millens and their children to be his second family.[16] Maria bought a house and moved the Millens and José into it.[17]

Sarria did not have a relationship with his birth father, a man who showed no interest in him and failed to provide his family with financial support. Julio Sarria was eventually arrested for failure to pay child support. A judge ordered that he pay $5 to be released; this money was then turned over for Jose's care. Julio was arrested each month until he returned to Nicaragua in around 1926 or 1927; each time he paid the $5 and was released.[17] Julio died in Nicaragua in 1945. Years later, José learned that his father had acknowledged him as his first-born.[18]

Sarria attended the Emerson School for kindergarten and then, because he spoke only Spanish, was sent to private schools until learning English.[13] Sarria began dressing in female clothes at an early age and his family indulged him,[19] allowing him occasionally to go on family outings dressed as a girl.[13] In his youth, he studied ballet, tap dance,[20] and singing.[15]

When Sarria was around ten years old, he asked his mother how much money they had in the bank. Maria, who gave her money to her employer Mr. Jost to invest, asked to see the books. She discovered that Jost had been embezzling from her and from the other women whom she had referred to him. Jost was arrested, convicted and deported. Maria sued Jost's corporate partners and received a settlement but never recovered the bulk of the money. Unable to afford her house payments, Maria moved José and the Millen family to Redwood City in 1932.[21]

As a teenager, Sarria enrolled in Commerce High School, where he took advanced classes in French and German. With his Spanish and English, these brought his total languages to four.[22] His facility with languages led to his first serious relationship with another man. Sarria tutored Paul Kolish, an Austrian baron who fled to Switzerland when the Nazis invaded Austria. He brought with him his wife and son Jonathan, each of whom suffered from asthma and tuberculosis. When his wife died, he brought Jonathan to America.[23] Kolish found himself falling in love with his tutor and Sarria's family welcomed him and his son.[22] Sarria graduated from high school and enrolled in college to study home economics.[24]

Military service

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Sarria became determined to join the military, despite being, at just under 5 feet (1.52 meters) tall,[15] too short to meet the Army's height requirement. He seduced a major who was attached to the San Francisco recruiting station on the condition that the major approve Sarria's enlistment.[25] Jose Sarria was approved and entered the Army Reserve, continuing his studies as he waited to be called up to active duty. Shortly before he was scheduled for induction in the regular Army, his beloved second father, Charles Millen, died of a heart attack. Sarria's induction was delayed a month, then he was sworn in and ordered to Sacramento, California, for basic training with the Signal Corps.[26]

Because of his fluency in several languages, Sarria was assigned to Intelligence School. However, following a routine background check for security clearance, he was advised that he would no longer be in the program. Sarria assumed that it was because investigators discovered his homosexuality. "I mean I had no lisp, but I wasn't the most masculine guy in town ... So I think that they figured that I was a little bit gay."[27] Sarria officially remained attached to the Signal Corps but was ordered to Cooks and Bakers School and trained as a cook.[25] After graduating from cooking school, he was assigned to train as a scout, but deliberately failed the training because of the dangerous nature of the assignment. He was then assigned to the motor pool.[28]

Through his work at the motor pool, Sarria met a young officer named Major Mataxis.[29] He became the major's orderly, eventually running an officers' mess in occupied Germany[25] where he cooked for Mataxis and about ten other officers.[30] He was discharged from the Army in 1947,[31] at the rank of Staff Sergeant.[32]

Upon Sarria's return from overseas, Kolish began to worry about their future. The United States had no legal recognition for same-sex relationships and Kolish looked for a way to provide for Sarria after Kolish's death. He proposed marriage to Sarria's mother Maria. Maria was willing, but José refused to allow it. Given no other choice, Kolish contacted his only remaining adult relative, a brother who lived in Hollywood, and left instructions for the care of Sarria and his family.[33]

On Christmas Day 1947, Kolish and his son were struck by a drunk driver while driving to spend the holiday with Sarria and his family. Both were killed.[34] The coroner determined that Jonathan died first, meaning that Paul's brother inherited everything. The brother ignored Paul's wishes regarding Sarria. "I would have gotten one of the houses", Sarria claimed, "but he only gave me a little money and one ring. He claimed that was all Paul wanted me to have. He was so evil. He said afterwards, 'If you expect anything else, you're not going to get it.' "[35]

The Nightingale of Montgomery Street

Following his military service, Sarria returned to San Francisco. He enrolled in college with plans of becoming a teacher.[36] He and his sister Teresa began frequenting the Black Cat Bar, a center of the city's beat and bohemian scene. Sarria and Teresa both became smitten with a waiter named Jimmy Moore and bet as to which of them could get him into bed first. José won the bet and soon Moore and he were lovers.[37] Sarria began covering for Moore when he was unable to work and soon Black Cat owner Sol Stoumen hired him as a cocktail waiter.

At around this time, Sarria was arrested for solicitation[3] in a sting operation at the St. Francis Hotel. Sarria maintained his innocence, stating that the arresting officer knew him personally. "But they had to make an example of somebody ... I was in the wrong place at the wrong time."[38] Nonetheless, he was convicted and subjected to a large fine. Sarria, understanding that his conviction meant he could never become certified as a teacher, dropped out of college.[36] Unsure of how to find work, he took the advice of a drag performer named Michelle and entered a drag contest at an Oakland bar called Pearl's. Sarria took second place, winning a two-week performance contract at the bar at $50 a week. "I decided then to be the most notorious impersonator or homosexual or fairy or whatever you wanted to call me–and you would pay me for it."[39] Returning to San Francisco, he picked up some small singing jobs while still cocktail waiting at the Black Cat.[40]

One night at the Black Cat, Sarria recognized the piano player's rendition of Bizet's opera Carmen and began singing arias from the opera while he delivered drinks.[41] This quickly led to a schedule of three to four shows a night, along with a regular Sunday afternoon show. Sarria was billed as "The Nightingale of Montgomery Street".[42] Initially he focused on singing parodies of popular torch songs. Soon, however, Sarria was performing full-blown parodic operas in his natural high tenor. His specialty was a re-working of Carmen set in modern-day San Francisco. Sarria as Carmen would prowl through the popular cruising area Union Square. The audience cheered "Carmen" on as she dodged the vice squad and made her escape.[43]

Sarria encouraged patrons to be as open and honest as possible. "People were living double lives and I didn't understand it. It was persecution. Why be ashamed of who you are?"[44] He exhorted the clientele, "There's nothing wrong with being gay–the crime is getting caught", and "United we stand, divided they catch us one by one".[41] At closing time he would call upon patrons to join hands and sing "God Save Us Nelly Queens" to the tune of "God Save the Queen". Sometimes he would bring the crowd outside to sing the final verse to the men across the street in jail, who had been arrested in raids earlier in the night.[41] Speaking of this ritual in the film Word is Out, gay journalist George Mendenhall said:

It sounds silly, but if you lived at that time and had the oppression coming down from the police department and from society, there was nowhere to turn ... and to be able to put your arms around other gay men and to be able to stand up and sing 'God Save Us Nelly Queens' ... we were really not saying 'God Save Us Nelly Queens.' We were saying 'We have our rights, too.'[45]

Sarria fought against police harassment, both of gays and of gay bars. Raids on gay bars were routine, with everyone inside the raided bar taken into custody and charged with such crimes as being "inmates in a disorderly house". Although the charges were routinely dropped, the arrested patrons' names, addresses and workplaces were printed in the newspapers.[46] When charges were not dropped, the arrested men usually quietly pleaded guilty. Sarria encouraged men to plead not guilty and demand a jury trial.[41] Following Sarria's advice, more and more gay men began demanding jury trials, so many that court dockets were overloaded and judges began expecting that prosecutors have actual evidence against the accused before going to trial.[47] One favored harassment technique, employed especially on Halloween after midnight, was to arrest drag queens under an old city ordinance that made it illegal for a man to dress in women's clothing with an "intent to deceive". In consultation with attorney Melvin Belli, Sarria countered this tactic by distributing labels to his fellow drag queens (hand-made, in the shape of a black cat's head)[48] that read "I am a boy". If confronted, the queen would simply display the tag to prove that there was no intent to deceive. Sarria's actions helped bring an end to Halloween police raids.[36] Along with Guy Strait, Sarria formed the League for Civil Education (LCE) in 1960[36] or 1961.[49] The LCE, like other homophile organizations, ran educational programs on the topic of homosexuality and provided support for men being ostracized for being gay and for those caught in police raids.[50]

Political candidacy

During an intensive period of police pressure after the 1959 San Francisco mayoral election, in which the supposed leniency of city government toward homosexuals became an issue,[51] Sarria ran for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1961, becoming the first openly gay candidate for public office in the United States.[52] Although Sarria never expected to win[44] he almost did win by default. On the last day for candidates to file petitions, city officials realized that there were fewer than five candidates running for the five open seats, which would have guaranteed Sarria a seat. By the end of the day, a total of 34 candidates had filed.[53] LCE co-founder Strait began printing the LCE News in part to support Sarria's candidacy.[54] Sarria garnered some 6,000 votes in the citywide race,[52] finishing ninth.[44] This was not enough to win a seat but was enough to shock political pundits and set in motion the idea that a gay voting bloc could wield real power in city politics.[55] "[He] put the gay vote on the map", said Terence Kissack, former executive director of the GLBT Historical Society. "He made it visible and showed there was a constituency."[44] As Sarria put it, "From that day on, nobody ran for anything in San Francisco without knocking on the door of the gay community."[56]

In 1962, Sarria along with bar owners and employees formed the Tavern Guild, the country's first gay business association.[57] The Guild raised money for legal fees and bail for people arrested at gay bars and helped bar owners coordinate their response to the harassment by the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control and the police.[58]

Sarria continued to perform and agitate at the Black Cat until, after some 15 years of unrelenting police pressure, the bar lost its liquor license in 1963.[59] The Black Cat stayed open as a luncheonette for a few more months before finally closing for good in February 1964.[60]

José I, The Widow Norton

With the demise of the Black Cat, Sarria helped found the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) in 1963. SIR grew out of a split between Sarria and Strait over the direction that LCE was heading. Strait and his supporters wanted to focus more on publishing the group's newsletter, while Sarria and his backers wanted to maintain focus on street-level organizing.[61] SIR sponsored both social and political functions, including bowling leagues, bridge clubs, voter registration drives and "Candidates' Nights" and published its own magazine, Vector.[52] In association with the Tavern Guild, SIR printed and distributed "Pocket Lawyers". These pocket-sized guides offered advice on what to do if arrested or harassed by police.[62] SIR lasted for 17 years.[63]

Crowned Queen of the Beaux Arts Ball in 1964 by the Tavern Guild, Sarria, stating that he was "already a queen", proclaimed himself "Her Royal Majesty, Empress of San Francisco, José I, The Widow Norton". Sarria devised the name "Widow Norton" as a reference to the much-celebrated citizen of 19th century San Francisco, Joshua Norton, who had declared himself Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico in 1859.[64] Sarria organized elaborate annual pilgrimages to lay flowers on Norton's grave in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Colma, California.[65] He purchased a plot adjacent to Norton's where he is now interred.[66]

Sarria's assumption of the title of Empress led to the establishment of the Imperial Court System, a network of non-profit charitable organizations throughout the United States, Canada, and Mexico that raises money for various beneficiaries. Sarria is much revered within the hierarchy of the Imperial Court System and is affectionately and informally known as "Mama" or "Mama José" among Imperial Court members.[67] The "José Honors Awards" are presented to Imperial Court dignitaries and others in a bi-annual banquet held in Sarria's honor.

Restaurateur

In 1964, Sarria went into business with restaurateur Pierre Parker, who owned restaurants called "Lucky Pierre" in Carmel, California, and New York City.[68] They met when Parker wandered into the Black Cat one night and they struck up a friendship.[69] In addition to his restaurants, Parker held the French food concession for the World's Fair.[60] He invited Sarria to join him at the 1964 New York World's Fair.

While working at the Fair, Sarria learned that his longtime companion, Jimmy Moore, had died. Moore had been a frequent drinker throughout their relationship and had been arrested a number of times for public drunkenness. A judge finally told Moore that the next time he was arrested he would be given the maximum sentence. Moore was arrested again and, scared of a long prison term, hanged himself in jail.[70] Although devastated, Sarria could not come home from the exposition. At the end of the season he returned and he and Moore's father consoled each other. "And so, that ended my big romance. The great love of my life. It carried on for nine years."[71]

Sarria and Parker worked together through both seasons of the New York fair, Expo 67 in Montreal, HemisFair '68 in San Antonio, Texas and Expo '74 in Spokane, Washington,[72] after which Sarria retired. He and Parker moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where Sarria lived until returning to San Francisco in 1977.[73] He remained politically active, endorsing the candidacies of Harvey Milk for the Board of Supervisors.[74] In 1977, Milk would win the board seat that Sarria had sought in 1961.[75]

Later life

Sarria and members of the Imperial Court appeared along with other notable drag queens in the 1995 film To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar. They played the judges of the "Drag Queen of the Year Contest" that opened the film.

In 2005, Sarria found himself at the center of a legal controversy over his role on the jury in the 1991 murder trial of Clifford Bolden. Bolden had been sentenced to death in 1991 for the 1986 murder of Henry Michael Pederson, whom Bolden allegedly picked up in a bar in San Francisco's Castro district. Bolden's attorneys claimed that Sarria, who was not on the jury that convicted Bolden but was seated as an alternate for the penalty phase, had known Bolden's lover, Pederson and another of the jurors. They alleged that he had concealed this knowledge in order to remain on the jury and push for a death sentence. Sarria acknowledged having spoken occasionally with the other juror but denied the rest of the allegations.[76] Sarria was cleared of wrongdoing in February 2008.[77]

Sarria was honored in 2005 with the San Francisco LGBT Pride Celebration Committee's Lifetime Achievement Grand Marshal Award.[78] On May 25, 2006, Sarria's lifetime of activism was commemorated when the city of San Francisco renamed a section of 16th Street in the Castro to José Sarria Court.[42] A plaque outlining Sarria's accomplishments is embedded in the sidewalk in front of the Harvey Milk Memorial Branch of the San Francisco Public Library, which is located at 1 José Sarria Court.[79] In 2009, the California State Assembly honored Sarria during an official celebration of LGBT Pride Month on June 21.[80]

Sarria reigned over the Imperial Court System until February 17, 2007, abdicating the throne in favor of his first heir apparent, Nicole Murray-Ramirez, who assumed the title Empress Nicole the Great, Queen Mother of the Americas.[81] This abdication marked the end of a 42-year reign of pioneering political activism and unforgettable queer pageantry. [82]

Sarria left San Francisco in 1996, settling in the Palm Springs, California,[64] area for more than a decade before moving to Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, New Mexico, a suburb of Albuquerque.[83][84] [85] On granting Sarria its Lifetime Achievement Award in March 2012, Albuquerque Pride noted that he was living in Los Ranchos in "a cute little casita and is enjoying his time raising chickens."[86] The "casita" was the guest house adjacent to the home of Tony Ross and his husband PJ Sedillo (also known as Fontana DeVine, Imperial Dowager Empress VI of the United Court of the Sandias); Ross and Sedillo served as Sarria's caregivers in the last three years of his life.[87]

Death

Sarria died of adrenal cancer at the age of 89 or 90 on August 19, 2013, at his home in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque.[85] [88][89] Obituaries and tributes appeared around the United States in media including The Advocate, KALW Public Radio (San Francisco), The New York Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle. Media outside the United States that reported the death include Gay Star News, an online newspaper based in London; Replika, a monthly LGBT magazine in Warsaw, Poland; Roze Golf, a regional LGBT radio program and online magazine based in Enschede, Netherlands; the website of RTVE, the Spanish national public television network; and Svenska Dagbladet, a daily newspaper in Stockholm, Sweden.

Sarria's imperial-drag-themed funeral was held on September 6, 2013, at Grace Cathedral of San Francisco, with the Right Rev. Marc Handley Andrus, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of California, presiding; some 1,000 mourners attended the service.[90] Various local and state elected officials participated, including California State Sen. Mark Leno, former San Francisco mayor Art Agnos, San Francisco Treasurer José Cisneros, and members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Leaders of the Imperial Court System and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence attended in full regalia, with the formal mourning dress for the court dictated by Sarria in advance.[91] Other dignitaries at the funeral included Stuart Milk, nephew of politician Harvey Milk and head of the Harvey Milk Foundation.[92][93]

Immediately following the funeral, a cortege of approximately 500 mourners accompanied Sarria's body to Woodlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Colma, where he was buried with full military honors in a plot he had previously purchased at the foot of the grave of Joshua Norton.[94]

Archives & memorabilia

Sarria documented his public and private activities throughout his life, amassing an extensive collection of archival materials and artifacts. He donated the majority of his papers and memorabilia, along with a sampling of his costumes, to the GLBT Historical Society, an archives and research center in San Francisco. An initial donation came in 1996 followed by another substantial body of material in 2012.[83][95]

In addition, Sarria gave a small selection of costumes, accessories and documents to the Oakland Museum of California—including a cape and headdress that he wore in performances of his comic version of Aida at The Black Cat.[96][97] An article published in The Atlantic in 2011 asserted that Sarria had also donated materials to the Smithsonian Institution.[98] This claim appears to be erroneous, as Sarria stated in 2012 that he declined the Smithsonian's request.[83]

In 2016, a group of individuals associated with various Imperial Courts created the José Sarria Foundation to further Sarria's memory and legacy. One of the aims of the group is to gather and preserve a collection Sarria's costume jewelry and other personal belongings that were auctioned by his estate.[99] Established as a 501(c)3 public charity in the state of Washington, the organization outlines its mission as follows: "The foundation is dedicated to keeping José Julio Sarria's memory alive for future generations ... continuing his life's work of philanthropy, balanced with a healthy dose of fun."[100]

Public commemorations

The San Francisco Pride Board created the José Julio Sarria History Makers award to honor LGBT people who make newsworthy accomplishments that were not going to get the recognition. It was created shortly before Sarria's death.[101]

Sarria is one of the LGBT historic figures honored on the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco's Castro District. A bronze plaque in Sarria's memory was dedicated as part of the honor walk on Castro Street in November 2017.[102]

On Wednesday, June 12, 2019, José Sarria was featured in the daily segment: "Pride Month F.Y.I." on the television talk show The View during a Pride Month salute. A leading LGBTQ pioneer was featured every day during the month of June on the show.[103]

In June 2019, Sarria was one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.[104][105] The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history,[106] and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[107]

In 2022, Sarria was honored with a star on the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs. His star is on Museum Way near a statue of Marilyn Monroe.[108]

Fictional portrayals

In 2017, Michael DeLorenzo portrayed Sarria in the miniseries about the history of the modern LGBT movement called When We Rise.

In 2020, Sarria was portrayed in the HBO docu-drama Equal.

Notes

- Ancestry.com. California Birth Index, 1905–1995 [database online]. Provo, Utah, US: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- "Imperial Council SF Founder". Imperial Council San Francisco. 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Aldrich, et al. p. 370

- Gorman, Michael R. (1998). The Empress Is a Man: Stories from the Life of José Sarria. New York: Routledge. pp. 14–6. ISBN 0789002590.

- Gorman p. 17

- Gorman p. 19–20

- Gorman p. 20–1

- Gorman p. 23

- Gorman pp. 24–5

- Gorman p. 26

- Gorman p. 27

- Pettis, Ruth M (2004). "Sarria, Jose (1923?)". glbtq. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

His birth certificate states December 12, 1923, but Sarria suspects that his mother added a year to deflect attention from her unmarried state.

- Boyd p. 20

- Gorman p. 31

- Bullough p. 376

- Gorman p. 35

- Gorman p. 36

- Gorman p. 72

- Shilts p. 51

- Boyd p. 22

- Gorman pp. 45–7

- Gorman p. 63

- Gorman pp. 60–1

- Gorman p. 77

- Bullough pp. 376–7

- Gorman pp. 80–1

- Gorman p. 87

- Gorman p. 90

- Gorman p. 91

- Gorman p. 92

- Gorman

- Gorman p. 95

- Gorman pp. 66–7

- Gorman p. 69

- Gorman p. 70

- Bullough p. 377

- Shilts pp. 51–2

- Gorman p. 139

- Loughery p. 216

- Boyd p. 21

- Shilts p. 52

- Dufty, Bevan (May 26, 2006). "Honoring a gay pioneer's contribution to San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- D'Emilio, John (2012). Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. London: University of Chicago Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0226922454.

- Olsen, David (May 24, 2006). "'Why be ashamed?' Desert resident was first openly gay political candidate". The Press-Enterprise. Archived from the original on June 30, 2006. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Mariposa Film Group (1977). Word is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives (Theatrical film). United States: Mariposa Film Group.

- Shilts p. 54

- Shilts p. 53

- Gorman p. 179

- Marcus p. 136

- Bullough p. 378

- Shilts pp. 55–6

- Miller p. 347

- Witt, et al. p. 8

- Carter p. 104

- Shilts pp. 56–7

- Lockhart p. 36

- Bullough p. 157

- D'Emilio p. 189

- Shilts p. 57

- Gorman p. 150

- Gorman p. 197

- D'Emilio p. 191

- Gorman p. 198

- Nash, Tammye (October 12, 2007). "Jose Sarria: Activist Empress". Dallas Voice. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Vigil, Delfin (February 21, 2005). "A gay court pays homage to its queer emperor". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Montanarelli, Lisa; Harrison, Ann (2005). Montanarelli, et al. non-numbered page. ISBN 9780762736812.

- "Founder of the International Court System Empress I Jose". International Court System. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- "Restaurant Guide". The New York Times. October 20, 1959. p. 44.

- Gorman p. 146

- Gorman p. 133

- Gorman p. 134

- Gorman p. 153

- Gorman p. 159

- Shilts p. 75

- Shilts p. 183

- Van Derbeken, Jaxon (July 17, 2005). "Death Row juror alleged to have secret vendetta". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Graham, S (February 13, 2008). "Judge: S.F. drag queen did not taint death case". ALM Research. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Sister Dana Van Iquity (April 28, 2005). "Parade Announces Lifetime Achievement Grand Marshal". San Francisco Bay Times. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- "Eureka Valley/Harvey Milk Branch Library". San Francisco Public Library. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- Aiello, Dan. "Assembly Proclaims June LGBT Pride Month Despite GOP Link To Prop 8". California Progress Report. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Baldwin, Anthony (November 2, 2006). "Imperial Court System founder Jose Sarria steps down". Gay & Lesbian Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Villegas, Jordan (May 20, 2021). ""The Empress is a Man": The Drag Royalty of José Julio Sarria". Latina. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- "Community leader, court founder José Sarria donates archives, costumes to Historical Society". History Happens. October 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Coe, Alexis (March 1, 2013). "Recent acquisitions: Gay icon, performer and "empress" José Sarria". San Francisco Weekly. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- Slotnik, Daniel E. (August 23, 2013). "José Sarria, Gay Advocate and Performer, Dies at 90". New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Albuquerque Pride (2012-05). "Honored dignitaries: Lifetime achievement award recipient" Archived September 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine; retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Tassy, Elaine (August 18, 2013). "Gay rights pioneer, WWII vet dies at age 90". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- "Jose Julio Sarria, founder of Imperial Court System, dies at 90". LGBT Weekly. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Brydum, Sunnivie (August 19, 2013). "Legendary Drag Queen José Julia Sarria Dead at 91". The Advocate. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- Bajko, Matthew S. (September 6, 2013). "Gay SF icon laid to rest". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- O'Connor, Lydia (September 7, 2013). "Jose Sarria, gay rights activist, leaves behind best funeral instructions ever". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- Christopher Harrity (September 8, 2013). "PHOTOS: Elegance and Honor, the State Funeral of José Sarria". The Advocate. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013.

- Carl Nolte (September 6, 2013). "Mourners celebrate gay rights pioneer Jose Sarria". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "Funeral fit for a queen". Bay Area Reporter. September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- José Sarria Papers (Collection No. 1996-01); GLBT Historical Society online catalog of archival collections; retrieved October 24, 2011.

- Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable of the Society of American Archivists. "Lavender Legacies Guide. United States: California"; retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Wood, Sura (April 29, 2010). "Bringing art to the people: The Oakland Museum reopens after renovation". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Sismondo, Christine (2011-11). "The Queen of San Francisco", The Atlantic.

- "About". José Sarria Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "A New Way to Honor Mama José". José Sarria Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "SF Pride 2013 Grand Marshal Lineup". Bay Times. May 30, 2013.

- "Second LGBT Honorees Selected for San Francisco's Rainbow Honor Walk". Rainbow Honor Walk. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "Pride Month FYI on "The View"". The View. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- Glasses-Baker, Becca (June 27, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor unveiled at Stonewall Inn". www.metro.us. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Rawles, Timothy (June 19, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor to be unveiled at historic Stonewall Inn". San Diego Gay and Lesbian News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Laird, Cynthia. "Groups seek names for Stonewall 50 honor wall". The Bay Area Reporter / B.A.R. Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Sachet, Donna (April 3, 2019). "Stonewall 50". San Francisco Bay Times. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "Sarria gets his star in Palm Springs". Bay Area Reporter.

References

- Aldrich, Robert and Garry Wotherspoon (2000). Who's Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History: From World War II to the Present Day. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22974-X.

- Boyd, Nan Alamilla (2003). Wide-open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20415-8.

- Bullough, Vern L. (2002). Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context. New York, Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56023-193-9.

- Carter, David (2005). Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York, MacMillan. ISBN 0-312-34269-1.

- D'Emilio, John (1983). Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14265-5.

- Gorman, Michael R. (1998). The Empress is a Man: Stories From the Life of José Sarria. New York, Harrington Park Press: an imprint of Haworth Press. ISBN 0-7890-0259-0 (paperback edition).

- Lockhart, John (2002). The Gay Man's Guide to Growing Older. Los Angeles, Alyson Publications. ISBN 1-55583-591-0.

- Loughery, John (1998). The Other Side of Silence: Men's Lives and Gay Identities: A Twentieth Century History. New York, Harry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-3896-5.

- Marcus, Eric (1992). Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights 1945 - 1990, An Oral History. New York, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-016708-4.

- Miller, Neil (1995). Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present. New York, Vintage Books. ISBN 0-09-957691-0.

- Montanarelli, Lisa, and Ann Harrison (2005). Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. San Francisco, Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-3681-X.

- Shilts, Randy (1982). The Mayor of Castro Street. New York, St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-52331-9.

- Witt, Lynn, Sherry Thomas and Eric Marcus (1995). Out in All Directions: The Almanac of Gay and Lesbian America. New York, Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67237-8.

External links

- GLBT Historical Society (San Francisco). Holds the personal papers of José Sarria (collection no. 1996-01).

- "José Sarria at Black Cat Cafe 1963." on YouTube Silent amateur movie (length: 1 minute, 56 seconds); from the José Sarria Papers at the GLBT Historical Society.

- José Sarria at IMDb