Johnny Poe

John Prentiss Poe Jr. (February 26, 1874 – September 25, 1915) was an American college football player and coach, soldier, Marine, and soldier of fortune, whose exploits on the gridiron and the battlefield contributed to the lore and traditions of the Princeton Tigers football program.

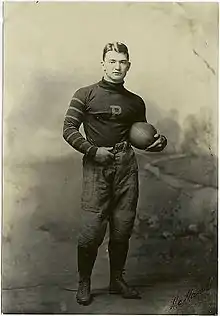

Poe pictured in The Official National Collegiate Athletic Association football guide, 1893 | |

| Born: | February 26, 1874 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died: | September 25, 1915 (aged 41) near Loos, France |

| Career information | |

| Position(s) | Halfback/Quarterback |

| College | Princeton |

| Career history | |

| As coach | |

| 1893–1894 | Virginia |

| 1896–1896 | Navy |

| 1897 | Princeton (assistant) |

| 1902–1903 | Princeton (assistant) |

| 1906 | Princeton (assistant) |

| 1908–1909 | Princeton (assistant) |

| As player | |

| 1891–1892 | Princeton |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Honduran Army |

| Years of service | 1898 1898–1899 1903 1907–1908 1914-1915 |

| Rank | Corporal (USA) Captain (Honduras) Private (Great Britain) |

| Unit | Royal Garrison Artillery the Black Watch |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War Philippine–American War Black Patch Wars Banana Wars World War I |

| Relations | Edgar Allan Poe (cousin) John P. Poe, Sr. (father) Edgar A. Poe (brother) Art Poe (brother) Gresham Poe (brother) Bradley T. Johnson (cousin) |

| Other work | cowboy, miner |

Biography

Family

Prentiss, known as "Johnny", was born February 26, 1874, in Baltimore, Maryland, to John Prentiss Poe Sr., and Anne Johnson Hough. He was the third of six sons in a family that also included three daughters. John Sr. was a prominent attorney, and relative[1] of the American writer and poet, Edgar Allan Poe. John Sr. was an 1856 graduate of Princeton University and would later serve as Attorney General of Maryland. Anne Hough was from a Maryland family who supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Her nephew, Bradley T. Johnson served as a Confederate general, and her brother, Gresham Hough, fought with Mosby's raiders.[2]

All six Poe brothers attended The Carey School for Boys which later became the Boys' Latin School of Baltimore and all wound up playing football for Princeton. The oldest, S. Johnson Poe, played halfback and also played on Princeton's national champion lacrosse team. The second son, Edgar A. Poe, was captain of the football team, and later served as Attorney General of Maryland, like his father. The fourth son, Neilson Poe, also played halfback. Fifth son, Arthur Poe, was voted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1969. Finally, the sixth son, Gresham Poe, played quarterback, and followed Johnny as head coach at Virginia.[3]

College football career

Poe enrolled at Princeton University in the fall of 1891, and was elected president of the freshman class. In spite of his small size, he made the varsity football team at halfback, and finished the season tied for third in touchdowns scored for the team. However, he struggled academically, and was asked to leave in the Spring. When he left for home, the entire freshman class escorted him to the train station.[4]

He re-enrolled the following Fall, and started at quarterback, moving to halfback midway through the season. Poe played even better than in his freshman year, finishing second on the team for touchdowns scored. However, he was once again forced to leave the university for scholastic reasons.[5]

After leaving Princeton, Poe bounced around, coaching two seasons at Virginia, working for a steamboat operator, selling real estate, coaching the Navy football team, and serving as an assistant coach at Princeton. Poe would often return to Princeton as an assistant coach, including the National Championship season of 1903. It was while serving as an assistant coach that Poe is credited with saying "If you won't be beat, you can't be beat," which became the team motto for many seasons.[6][7]

Soldier, adventurer

Poe enlisted in the Fifth Maryland Infantry Regiment, and after over three years had risen to the rank of corporal, when the United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. His regiment was mustered into Federal service on May 14, and sent to Tampa, Florida, on June 3, in preparation for an invasion of Cuba. However, the regiment was unable to obtain transport to Cuba, and spent the war in Tampa, and later in Huntsville, Alabama, before being mustered out of service on October 22,.[8] Poe worked as a cowpuncher in New Mexico, but longed for action and enlisted in the Regular Army's 23rd Infantry. He was sent to the island of Sulu in the Philippines, where he served in Company F and as an orderly on General Bates' staff, seeing none of the action he had been hoping for. Declining to apply for a commission, Poe instead asked his father to buy out his enlistment, and worked as a surveyor in Baltimore for a few months before returning to New Mexico.[9][10][6]

In 1903, Poe joined the Kentucky National Guard, his detachment of which was sent to Princeton, Kentucky, to suppress uprisings which led to the "Black Patch Wars". Later that year, he wrote to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, volunteering his services in the looming Panamanian revolution. He was enlisted and sailed for Panama aboard the USS Dixie, but saw no action, and he returned to the United States. There, he engaged briefly in the coal-mining business in Charleston, West Virginia, before moving to Tonopah, Nevada, to engage in silver mining there.[6][10]

Hearing that war was breaking out between Honduras and Nicaragua, Poe left Nevada in 1907, intending to join the Nicaraguan army. However, when his ship reached Honduras, anxious that the war was ending, he joined the army of Honduras. He was made a captain and put in charge of a gun in the siege of Amapala. The war ended with the defeat of Honduran forces, and Poe returned to Nevada and mining. The following year found him with General Rafael de Nogales Méndez on a filibustering expedition in Venezuela against the dictator, Cipriano Castro. Méndez eventually ran afoul of the new president, Juan Vicente Gómez, and went into exile. Poe returned once again to his mining interest, taking a two-year break, however, to join an expedition to survey the boundary between Alaska and Canada.[11][12]

Death

Within days of Britain's entry into World War I, Poe volunteered for the British Army and was assigned to the Royal Garrison Artillery, where he served in France for the remainder of 1914 and the first part of 1915. By then he had decided that artillery was too far behind the lines, and had himself transferred to the Black Watch, a famous Scottish infantry regiment, known to the Germans as the "Ladies from Hell" for the kilts they wore and their ferocity.[13]

In the opening hours of the Battle of Loos, on the morning of September 25, 1915, Poe was with a detachment carrying bombs to another regiment and was part way across an open field, when he was struck in the stomach by a bullet and killed. He was later buried there, between the German and British lines. However, his friends and relatives were never able to locate his grave.[14][15]

Legacy

Poe's name was entered into the Black Watch roll of honor at Edinburgh Castle. At Princeton, Poe field was named in his honor. Given annually and established by Poe's mother, the "John Prentiss Poe, Jr. Memorial Football Cup" (presently known as the Poe-Kazmaier Trophy) is the highest award given to a Princeton football player.

Head coaching record

| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia Orange and Blue (Independent) (1893–1894) | |||||||||

| 1893 | Virginia | 8–3 | |||||||

| 1894 | Virginia | 8–2 | |||||||

| Virginia: | 16–5 | ||||||||

| Navy Midshipmen (Independent) (1896) | |||||||||

| 1896 | Navy | 5–3 | |||||||

| Navy: | 5–3 | ||||||||

| Total: | 21–8 | ||||||||

References

Footnotes

- first cousin once removed, Street, p.117.

- Porter.

- Presby & Moffatt, pp. 341–345.

- Presbrey and Moffat, pp. 345–349.

- Presbrey and Moffatt, pp. 349–354.

- Washington Bee.

- Edwards, p. 418.

- Imbrie, pp. 488–489.

- The New York Times, December 2, 1901.

- The Washington Times, December 28, 1903.

- The New York Times, October 30, 1915.

- The New York Times, May 7, 1907.

- The New York Times, October 30, 1915.

- The New York Times, October 30, 1915

- Edwards, p. 181.

Sources

- "Ex-Football Hero In War" (PDF). The New York Times. May 7, 1907. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- "'Johnny' Poe Killed Fighting in France" (PDF). The New York Times. October 30, 1915. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- "Poe is on the Dixie Sailing to Panama". The Washington Times. December 28, 1903. p. 2. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- "Soldier of Fortune". Washington Bee. October 5, 1907. p. 7. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- "Transport Arrives From Philippines" (PDF). The New York Times. December 2, 1901. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- Bernstein, Mark F. (September 10, 2003). "A Princeton hero's search for meaning". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- Edwards, William H. (1916). Football Days – Memories of the Game and of the Men Behind the Ball (PDF). Moffat, Yard & Company. p. 418. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- Imbrie, Andrew Clerk, ed. (1905). The Class of 1895 Princeton University Decennial Record, 1895–1905 (PDF). pp. 322–327 & 488–489. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Morse, Edwin W. (1918). "John P. Poe of the First Black Watch". The Vanguard of American Volunteers in the Fighting Lines and in Humanitarian Service August, 1914 – April, 1917 (PDF). Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 75–82. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Porter, David L., ed. (1987). Biographical Dictionary of American Sports – Football. Greenwood Press. p. 474. ISBN 0-313-25771-X.

- Presbrey, Frank; Moffatt, James Hugh (1901). Athletics at Princeton – A History (PDF). Frank Presbrey Co. pp. 341–354. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Street, Julian (1917). "The Story of 'Johnnie' Poe". In Charles Hanson Towne (ed.). For France (PDF). Doubleday, Page & Co. pp. 116–121. Retrieved February 25, 2008.