Jelling stones

The Jelling stones (Danish: Jellingstenene) are massive carved runestones from the 10th century, found at the town of Jelling in Denmark. The older of the two Jelling stones was raised by King Gorm the Old in memory of his wife Thyra. The larger of the two stones was raised by King Gorm's son, Harald Bluetooth, in memory of his parents, celebrating his conquest of Denmark and Norway, and his conversion of the Danes to Christianity. The runic inscriptions on these stones are considered the best known in Denmark.[1] In 1994, the stones, in addition to the burial mounds and small church nearby, were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as an unparalleled example of both pagan and Christian Nordic culture.[2]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Jelling stones, in their glass casing (2012) | |

| Location | Jelling, Denmark |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii |

| Reference | 697 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Area | 4.96 ha |

| Coordinates | 55°45′24″N 9°25′10″E |

Location of Jelling stones in Denmark | |

Significance

The stones are strongly identified with the creation of Denmark as a nation state. Both inscriptions mention the name "Danmark" (in the form of accusative "tanmaurk" ([dɑnmɒrk]) on the large stone, and genitive "tanmarkar" (pronounced [dɑnmɑrkɑɹ̻̊˔]) on the small stone).[3]

The larger stone explicitly mentions the conversion of Denmark from Norse paganism and the process of Christianization, alongside a depiction of the crucified Christ; it is therefore popularly dubbed "Denmark's baptismal certificate" (Danmarks dåbsattest), an expression coined by art historian Rudolf Broby-Johansen in the 1930s.[4]

Recent history

After having been exposed to the elements for a thousand years, cracks are beginning to show. On 15 November 2008 experts from UNESCO examined the stones to determine their condition. Experts requested that the stones be moved to an indoor exhibition hall, or in some other way protected in situ, to prevent further damage from the weather.[5]

In February 2011 the site was vandalized using green spray paint, with the word "GELWANE" written on both sides of the larger stone, and with identical graffiti sprayed on a nearby gravestone and on the church door.[6] After much speculation about the possible meaning of the enigmatic word "gelwane",[7] the vandal was eventually discovered to be a 15-year-old boy with Asperger's syndrome and the word itself was meaningless.[8][9][10] As the paint had not fully hardened,[9] experts were able to remove it.[11]

The Heritage Agency of Denmark decided to keep the stones in their current location and selected a protective casing design from 157 projects submitted through a competition. The winner of the competition was Nobel Architects.[12] The glass casing creates a climate system that keeps the stones at a fixed temperature and humidity and protects them from weathering.[13] The design features rectangular glass casings strengthened by two solid bronze sides mounted on a supporting steel skeleton. The glass is coated with an anti-reflective material that gives the exhibit a greenish hue. Additionally, the bronze patina gives off a rusty, greenish colour, highlighting the runestones' gray and reddish tones and emphasising their monumental character and significance.[13]

Runestone of Harald Bluetooth

The inscription on the larger of the two Jelling stones (Jelling II, Rundata DR 42) translates to:

King Haraldr ordered this monument made in memory of Gormr, his father, and in memory of Thyrvé, his mother; that Haraldr who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.

In normalized Old Norse:

Haraldr konungr bað gǫrva kumbl þausi aft Gorm faður sinn auk aft Þórví móður sína. Sá Haraldr es sér vann Danmǫrk alla auk Norveg auk dani gærði kristna.[14]

Danish translation:

Kong Harald bød gøre disse kumler efter Gorm, sin fader, og efter Thyre, sin moder, den Harald, som vandt sig hele Danmark og Norge og gjorde danerne kristne.[15]

| Transcription | Transliteration[16] | |

| (side A) | ᚼᛅᚱᛅᛚᛏᚱ ᛬ ᚴᚢᚾᚢᚴᛦ ᛬ ᛒᛅᚦ ᛬ ᚴᛅᚢᚱᚢᛅ ᚴᚢᛒᛚ ᛬ ᚦᛅᚢᛋᛁ ᛬ ᛅᚠᛏ ᛬ ᚴᚢᚱᛘ ᚠᛅᚦᚢᚱ ᛋᛁᚾ ᛅᚢᚴ ᛅᚠᛏ ᛬ ᚦᚭᚢᚱᚢᛁ ᛬ ᛘᚢᚦᚢᚱ ᛬ ᛋᛁᚾᛅ ᛬ ᛋᛅ ᚼᛅᚱᛅᛚᛏᚱ (᛬) ᛁᛅᛋ ᛬ ᛋᚭᛦ ᛫ ᚢᛅᚾ ᛫ ᛏᛅᚾᛘᛅᚢᚱᚴ | haraltr : kunukʀ : baþ : kaurua kubl : þausi : aft : kurm faþur sin auk aft : þąurui : muþur : sina : sa haraltr (:) ias : sąʀ * uan * tanmaurk |

| (side B) | ᛅᛚᛅ ᛫ ᛅᚢᚴ ᛫ ᚾᚢᚱᚢᛁᛅᚴ | ala * auk * nuruiak |

| (side C) | ᛫ ᛅᚢᚴ ᛫ ᛏ(ᛅ)ᚾᛁ (᛫ ᚴᛅᚱᚦᛁ ᛫) ᚴᚱᛁᛋᛏᚾᚭ | * auk * t(a)ni (* karþi *) kristną |

The stone has a figure of the crucified Christ on one side and on another side a serpent wrapped around a lion. Christ is depicted as standing in the shape of a cross and entangled in what appear to be branches.[17] This depiction of Christ has often been taken as indicating the parallels with the "hanging" of the Norse pagan god Odin, who in Rúnatal gives an account of being hanged from a tree and pierced by a spear.[17]

.jpg.webp)

Modern copies of the runestone of Harald Bluetooth

Another copy of this stone was placed in 1936 on the Domplein ('Dom Square') in Utrecht in the Netherlands, next to the Cathedral of Utrecht, on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of Utrecht University.

In 1955, a plaster cast of this stone was made for a festival in London. It is now located in the grounds of the Danish Church in London, 4 St Katherines Precinct, Regents Park, London. The copy is painted in bright colours, like the original. Most of the original paint has flaked away from the original stone, but enough small specks of paint remained to enable the determination of what the colours looked like when they were freshly painted. A copy is also located in the National Museum of Denmark, and another copy, decorated by Rudolf Broby-Johansen in the 1930s, just outside the Jelling museum, which stands within sight of the Jelling mounds.[18]

A copy exists in Rouen, Normandy, France, near Saint-Ouen Abbey Church, offered by Denmark to the city of Rouen, on the occasion of the millennium of Normandy in 1911.

A facsimile of the image of Christ on Harald's runestone appears on the inside front cover of Danish passports.[19]

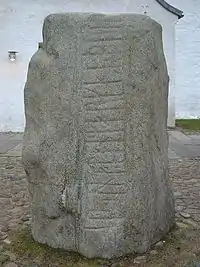

Runestone of Gorm

The inscription on the older and smaller of the Jelling stones (Jelling I, Rundata DR 41) translates to "King Gormr made this monument in memory of Thyrvé, his wife, Denmark's adornment."

| Transcription | Transliteration[20] | |

| (side A) | ᛬ ᚴᚢᚱᛘᛦ ᛬ ᚴᚢᚾᚢᚴᛦ ᛬ ᛬ ᚴ(ᛅᚱ)ᚦᛁ ᛬ ᚴᚢᛒᛚ ᛬ ᚦᚢᛋᛁ ᛬ ᛬ ᛅ(ᚠᛏ) ᛬ ᚦᚢᚱᚢᛁ ᛬ ᚴᚢᚾᚢ | : kurmʀ : kunukʀ : : k(ar)þi : kubl : þusi : : a(ft) : þurui : kunu |

| (side B) | ᛬ ᛋᛁᚾᛅ ᛬ ᛏᛅᚾᛘᛅᚱᚴᛅᛦ ᛬ ᛒᚢᛏ ᛬ | : sina : tanmarkaʀ : but : |

See also

- Boris stones — similar landmarks in Belarus

- Curmsun Disc

- Bornholm amulet

- Haraldskær Woman

- Jelling stone ship — a ship setting that lay between the mounds

- Jelling style

- List of runestones

- Tourism in Denmark

References

- Jelling stones. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- "Jelling Mounds, Runic Stones and Church". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 19 Jun 2021.

- Thunberg, Carl L. (2012). Att tolka Svitjod. Göteborgs universitet. CLTS. p. 51. ISBN 978-91-981859-4-2.

- Lokalhistorie fra Sydøstjylland Archived 2021-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, Historisk Samfund for Sydøstjylland og bidragyderne (2010), p. 83.

- "Eksperter: Runestenene skal reddes". Danmarks Radio. 16 November 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- Politiken.dk: Jellingstenene hærget af graffiti

- More Jelling Stones graffiti: Gelwane the Second and Web mining

- Politiken.dk

- Ritzau (20 February 2011). Jellingstenen skal renses hurtigst muligt. Kriteligt Dagblad. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Gelwane" art project

- Skarum, S. (7 March 2011). Jellingstenen er reddet – næsten. Berlinske. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Jelling Stones get designer cases". Copenhagen Post. 5 March 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- Covering of the runic stones in Jelling, Denmark Archived 2013-04-14 at archive.today. – Copper Concept. Access date: 13 July 2012.

- Stefan Brink, Neil Price, The Viking World, Routledge (2008), p. 277.

- "Jellingstenene, ca. 950-965". danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- (Jacobsen & Moltke, 1941–42, DR 42)

- Kure, Henning (2007). "Hanging on the World Tree: Man and Cosmos in Old Norse Mythic Poetry". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes, and Interactions. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. pp. 68–73. ISBN 978-91-89116-81-8. pp. 69–70.

- Jellingstenen – en del af historiekanonen Archived 16 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Lærere i grundskolen: Historie, EMU, Danmarks Undervisningsportal (in Danish)

- "Council of Europe". Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- (Jacobsen & Moltke, 1941–42, DR 41)

Further reading

- Hogan, C. Michael. "Jelling Stones," Megalithic Portal, editor Andy Burnham

- Rundata, Joint Nordic database for runic inscriptions.

- Jacobsen, Lis; Moltke, Erik (1941–42). Danmarks Runeindskrifter. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaards Forlag.