Jean-Pierre Blanchard

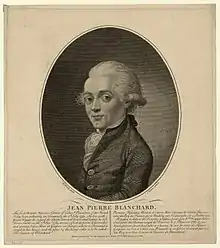

Jean-Pierre [François] Blanchard (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ pjɛʁ blɑ̃ʃaʁ]; 4 July 1753 – 7 March 1809) was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular the first aerial crossing of the English Channel, on 7 January 1785.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard | |

|---|---|

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, engraving after a portrait by Richard Livesay | |

| Born | 4 July 1753 |

| Died | 7 March 1809 (aged 55) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Ballooning |

| Spouse(s) | Victoire Lebrun {abandoned} Marie Madeleine-Sophie Armant |

Biography

1784 - Flights in Paris

Blanchard made his first successful balloon flight in Paris on 2 March 1784, in a hydrogen gas balloon launched from the Champ de Mars. The first successful manned balloon flight had taken place on 21 November 1783, when Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d'Arlandes took off at Palace of Versailles in a free-flying hot air balloon constructed by the Montgolfier brothers. The first manned hydrogen balloon flight had taken place on 1 December 1783, when Professor Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert launched the first gas balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris. Blanchard's flight nearly ended in disaster, when one spectator (Dupont de Chambon, a contemporary of Napoleon at the École militaire de Brienne) slashed at the balloon's mooring ropes and oars with his sword after being refused a place on board. Blanchard intended to "row" northeast to La Villette but the balloon was pushed by the wind across the Seine to Billancourt and back again, landing in the rue de Sèvres. Blanchard adopted the Latin tag Sic itur ad astra as his motto.

The early balloon flights triggered a phase of public "balloonomania", with all manner of objects decorated with images of balloons or styled au ballon, from ceramics to fans and hats. Clothing au ballon was produced with exaggerated puffed sleeves and rounded skirts, or with printed images of balloons. Hair was coiffed à la montgolfier, au globe volant, au demi-ballon, or à la Blanchard.[1]

1784 - Flights in London

Blanchard moved to London in August 1784, where he took part in a flight on 16 October 1784 with John Sheldon, just a few weeks after the first flight in Britain (and the first outside France), when Italian Vincenzo Lunardi flew from Moorfields to Ware on 15 September 1784. Blanchard's propulsion mechanisms – flapping wings and a windmill – again proved ineffective, but the balloon flew some 115 km from Lewis Lochée’s military academy in Little Chelsea, landing in Sunbury and then taking off again to end in Romsey. Blanchard took a second flight on 30 November 1784, taking off with an American, Dr John Jeffries, from the Rhedarium behind Green Street[2] Mayfair, London to Ingress in Kent.

1785 - First flight over the English Channel

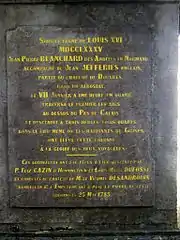

MDCCLXXXV

Jean-Pierre Blanchard of Les Andelys in Normandy

accompanied by Jean Jefferies English (sic)

Leaving from Dover Castle

in an Aerostat.

January 7th at a quarter past one,

was the first to cross the air

above Pas-de-Calais

and descended after three and a quarter hours

in the very place where the inhabitants of Guines

raised this column

to the glory of the two travellers.

These aeronauts were received on their descent by

P. Eliz Casin d'Honnincthun and Louis Marie Dufosse.

and taken to the castle of M.Le Vicomte Desandrouin

Chamberlain of the Emperor who laid the stone of this

column on May 25, 1785.[Note 1]

A third flight, again with Jeffries, was the first flight over the English Channel, taking about 2½ hours to travel from England to France on 7 January 1785,[3][4][5] flying from Dover Castle to Guînes. Blanchard was awarded a substantial pension by Louis XVI. The King ordered the balloon and boat be hung up in the church of Église Notre-Dame de Calais.[6] (A subsequent Channel crossing attempt in the opposite direction by Pilâtre de Rozier on 15 June 1785 ended unsuccessfully in a fatal crash.)[7]

Flights in Europe

Blanchard toured Europe, demonstrating his balloons. He holds the record of first balloon flights in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland. Among the events that included demonstrations of his abilities as a balloonist was the coronation of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II as King of Bohemia in Prague in September 1791.

Following the invention of the modern parachute in 1783 by Sébastien Lenormand in France, in 1785 Jean-Pierre Blanchard demonstrated it as a means of jumping safely from a balloon. While Blanchard's first parachute demonstrations were conducted with a dog as the passenger, he later had the opportunity to try it himself when in 1793 his hydrogen balloon ruptured and he used a parachute to escape. Subsequent development of the parachute focused on making it more compact. While the early parachutes were made of linen stretched over a wooden frame, in the late 1790s, Blanchard began making parachutes from folded silk, taking advantage of silk's strength and light weight.

1793 - Flights in America

On 9 January 1793, Blanchard conducted the first balloon flight in the Americas.[8] He launched his balloon from the prison yard of Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and landed in Deptford, Gloucester County, New Jersey. One of the flight's witnesses that day was President George Washington, and the future presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were also present. Blanchard left the United States in 1797.

Personal life and death

He married Marie Madeleine-Sophie Armant (better known as Sophie Blanchard) in 1804. On 20 February 1808 Blanchard had a heart attack while in his balloon at The Hague. He fell from the balloon and died roughly a year later on 7 March 1809 due to severe injuries. His widow continued to support herself with ballooning demonstrations until doing so also killed her.[9]

Pictures

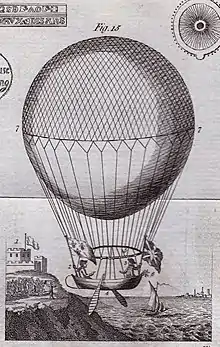

Airship designed by Jean-Pierre Blanchard, 1784

Airship designed by Jean-Pierre Blanchard, 1784.jpg.webp) Crossing of the English Channel by Blanchard and Jeffries on 7 January 1785.

Crossing of the English Channel by Blanchard and Jeffries on 7 January 1785. Crossing of the English Channel by Blanchard in 1785.

Crossing of the English Channel by Blanchard in 1785..jpg.webp) Walnut Street Jail, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Blanchard launched his 9 January 1793 American flight from the prison yard.

Walnut Street Jail, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Blanchard launched his 9 January 1793 American flight from the prison yard. La 14e expérience aérostatique de Monsieur Blanchard accompagné du Chevalier Lépinard, Lille, 26 août 1785, painting by Louis Joseph Watteau

La 14e expérience aérostatique de Monsieur Blanchard accompagné du Chevalier Lépinard, Lille, 26 août 1785, painting by Louis Joseph Watteau Blanchard and Jeffries Crossing the English Channel in 1785

Blanchard and Jeffries Crossing the English Channel in 1785

Notes

- Original text of Blanchard's Column at Guînes: Sous le régné de Louis XVI MDCCLXXXV, Jean-Pierre Blanchard des Andelys en Normand, Accompagne de Jean Jefferies Anglais, Partit du chateau de Douvre dans un Aérostat, Le VII Janvier a une heure un quart, traversa le prémier les airs au dessus de Pas-de-Calais, et descendit de trois heures trois quarts dans le lieux même ou les habitants de Guînes. Ont élevé cette colonne À la gloire des deux voyageurs.

Ces aeronauts en été recus à leur descent par P. Eliz Casin d'Honnincthun et Louis Marie Dufossé, Et conduits au château de M.Le Vicomté Desandrouin, Chambellan de L'Empereur qui a posé la pierre de cette colonne le 25 Mai 1785.

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-29. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The Rhedarium had been built as military stables in 1738 and then sold, in 1784, to be used as a coach manufact by a Mr. Murdoch MacKenzie." (Blog: The Early London Gas Industry: The Rhedarium); see The Survey of London,, vol 40: The Green Street Area, Introduction, and ibid "Wood's Mews".

- Blanchard, Jean-Pierre-François. (subscription required) Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford. p. 286.

- "1785: Across the English Channel in a balloon". The History Channel. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Canterbury. Extract of an authentic Letter from Dover. Jan. 20, 1785". Kentish Gazette. England. 22 January 1785. Retrieved 13 November 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Holmes 2008, pp. 148−155.

- Beischer, DE; Fregly, AR (1962). "Animals and man in space. A chronology and annotated bibliography through the year 1960". US Naval School of Aviation Medicine. ONR TR ACR-64 (AD0272581). Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Her death is described in detail, with multiple citations, in the Wikipedia article about her.

References

- Holmes, Richard (2008). The age of wonder. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-3187-0.