James Ensor

James Sidney Edouard, Baron Ensor (13 April 1860 – 19 November 1949)[1] was a Belgian painter and printmaker, an important influence on expressionism and surrealism who lived in Ostend for most of his life. He was associated with the artistic group Les XX.

James Ensor | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait of James Ensor by his Easel, 1890 | |

| Born | James Sidney Ensor 13 April 1860 |

| Died | 19 November 1949 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Education | Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, Brussels (Belgium) |

| Known for | Painting, graphic arts |

Biography

Ensor's father, James Frederic Ensor, born in Brussels to English parents,[2] was a cultivated man who studied engineering in England and Germany.[3] Ensor's mother, Maria Catherina Haegheman, was Belgian. Ensor himself lacked interest in academic study and left school at the age of fifteen to begin his artistic training with two local painters. From 1877 to 1880, he attended the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where one of his fellow students was Fernand Khnopff.[4] Ensor first exhibited his work in 1881. From 1880 until 1917, he had his studio in the attic of his parents' house. His travels were very few: three brief trips to France and two to the Netherlands in the 1880s,[5] and a four-day trip to London in 1892.[6]

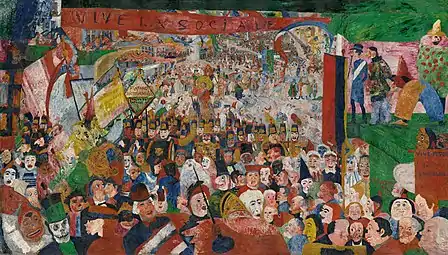

During the late 19th century, much of Ensor's work was rejected as scandalous, particularly his painting Christ's Entry Into Brussels in 1889 (1888–89). The Belgian art critic Octave Maus famously summed up the response from contemporaneous art critics to Ensor's innovative (and often scathingly political) work: "Ensor is the leader of a clan. Ensor is the limelight. Ensor sums up and concentrates certain principles which are considered to be anarchistic. In short, Ensor is a dangerous person who has great changes. ... He is consequently marked for blows. It is at him that all the harquebuses are aimed. It is on his head that are dumped the most aromatic containers of the so-called serious critics." Some of Ensor's contemporaneous work reveals his defiant response to this criticism. For example, the 1887 etching "Le Pisseur" depicts the artist urinating on a graffitied wall declaring (in the voice of an art critic) "Ensor est un fou" or "Ensor is a Madman."[7]

Ensor's paintings continued to be exhibited and he gradually won acceptance and acclaim. In 1895 his painting The Lamp Boy (1880) was acquired by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, and he had his first solo exhibition in Brussels.[8] By 1920 he was the subject of major exhibitions; in 1929 he was named a Baron by King Albert, and was the subject of the Belgian composer Flor Alpaerts's James Ensor Suite; and in 1933 he was awarded the band of the Légion d'honneur. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, after considering Ensor's 1887 painting Tribulations of Saint Anthony (now in MoMA's collection), declared Ensor the boldest painter working at that time.[9]

Even in the first decade of the 20th century, however, Ensor's production of new works was diminishing, and he increasingly concentrated on music—although he had no musical training, he was a gifted improviser on the harmonium, and spent much time performing for visitors.[10] Against the advice of friends, he remained in Ostend during World War II despite the risk of bombardment. In his old age, he was an honored figure among Belgians, and his daily walk made him a familiar sight in Ostend.[11] He died there following a short illness, on 19 November 1949 at the age of 89.

Art

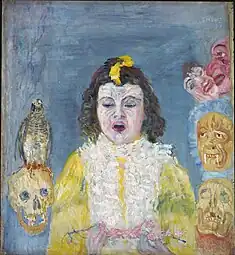

While Ensor's early works, such as Russian Music (1881) and The Drunkards (1883), depict realistic scenes in a somber style, his palette subsequently brightened and he favored increasingly bizarre subject matter. Such paintings as The Scandalized Masks (1883) and Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man (1891) feature figures in grotesque masks inspired by the ones sold in his mother's gift shop for Ostend's annual Carnival. Subjects such as carnivals, masks, puppetry, skeletons, and fantastic allegories are dominant in Ensor's mature work. Ensor dressed skeletons up in his studio and arranged them in colorful, enigmatic tableaux on the canvas, and used masks as a theatrical aspect in his still lifes. Attracted by masks' plastic forms, bright colors, and potential for psychological impact, he created a format in which he could paint with complete freedom.[12]

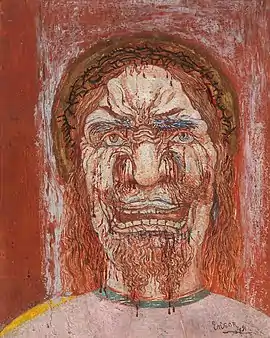

The four years between 1888 and 1892 mark a turning point in Ensor's work. He turned to religious themes, often the torments of Christ.[13] Ensor interpreted religious themes as a personal disgust for the inhumanity of the world.[13] In 1888 alone, he produced forty-five etchings as well as his most ambitious painting, the immense Christ's Entry Into Brussels in 1889.[14] Also known as Entry of Christ into Brussels, it is considered "a forerunner of twentieth-century Expressionism."[15] In this composition, which elaborates a theme treated by Ensor in his drawing Les Aureoles du Christ of 1885, a vast carnival mob in grotesque masks advances toward the viewer. Identifiable within the crowd are Belgian politicians, historical figures, and members of Ensor's family.[16] Nearly lost amid the teeming throng is Christ on his donkey; although Ensor was an atheist, he identified with Christ as a victim of mockery.[17] The piece, which measures 99+1⁄2 by 169+1⁄2 inches, was rejected by Les XX and was not publicly displayed until 1929.[15] After its controversial export in the 1960s, the painting is now at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.[15]

As Ensor achieved belated recognition in the final years of the 19th century, his style softened and he painted less in the 20th century. Historians have generally seen Ensor's last forty or fifty years as a long period of decline, although noting a few original "superb and poignant" compositions from his later period.[14] One author identified significant works of Ensor's late period such as The Artist's Mother in Death (1915), a subdued painting of his mother's deathbed with a still life of prominent medicine bottles in the foreground, and The Vile Vivisectors (1925), a vehement attack on those responsible for the use of animals in medical experimentation.[14] Another stated "He would still paint pictures magnificently vigorous and bold, but they would be exceptions rather than the rule" noting works such as Our Two Portraits (1905), The Deliverance of Andromeda (1925), Port of Ostend (1933), and Ensor at the Harmonium (1933).[18] The aggressive sarcasm that had characterized his work since the mid-1880s was less evident in his few new compositions, and much of his output consisted of mild repetitions of earlier works.[19] Several still life paintings, void of social, political, or introspective content, stand out among his later works. Ensor turned more and more to music in his later years, playing the harmonium and even composing a ballet-pantomime in one act, The Scale of Love (1907), complete with an original libretto, sets, and costumes. He is known to have stated in later years that he had followed the wrong path in life, feeling that he should have devoted himself to music.[20][21]

Gallery

Early work (1879–1884)

_-_De_vrouw_met_de_wipneus_001.jpg.webp) Woman with Turned-up Nose (1879), oil on canvas mounted on wood, 54 x 45 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Woman with Turned-up Nose (1879), oil on canvas mounted on wood, 54 x 45 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp_-_De_rog_001.jpg.webp) The Skate (c. 1880), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

The Skate (c. 1880), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp_-_Stilleven_met_chinoiserie%C3%ABn_001.jpg.webp) Still Life with Chinoiseries (1880), oil on canvas, 100 x 78 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

Still Life with Chinoiseries (1880), oil on canvas, 100 x 78 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp Afternoon in Ostend (1881), oil on canvas, 108 x 133 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Afternoon in Ostend (1881), oil on canvas, 108 x 133 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp_-_De_oestereetster_001.jpg.webp) The Oyster Eater (1882), oil on canvas, 207 x 150 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

The Oyster Eater (1882), oil on canvas, 207 x 150 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp_oil_on_canvas%252C_113_x_97.5_cm.%252C_Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg.webp) Meadow Flowers (1883), oil on canvas, 113 x 97.5 cm., Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Meadow Flowers (1883), oil on canvas, 113 x 97.5 cm., Minneapolis Institute of Arts The Rower (1883), Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

The Rower (1883), Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp_oil_on_canvas%252C_135_x_112_cm.%252C_Royal_Museums_of_Fine_Arts_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Scandalized Mask (1883), oil on canvas, 135 x 112 cm., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Scandalized Mask (1883), oil on canvas, 135 x 112 cm., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels_-_De_daken_van_Oostende_001.jpg.webp)

Mature work (1885–1899)

_-_Uitdrijving_Adam_en_Eva_uit_het_aards_paradijs_001.jpg.webp) Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise (1887), oil on canvas, 205 x 245 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise (1887), oil on canvas, 205 x 245 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp Tribulations of Saint Anthony (1887), oil on canvas, 117.8 x 167.6 cm., Museum of Modern Art, New York

Tribulations of Saint Anthony (1887), oil on canvas, 117.8 x 167.6 cm., Museum of Modern Art, New York Astonishment of the Mask Wouse (1889), oil on canvas, 131,5 x 109 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Astonishment of the Mask Wouse (1889), oil on canvas, 131,5 x 109 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889), oil on canvas, 74.8 x 60 cm., Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889), oil on canvas, 74.8 x 60 cm., Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth Attributes of the Studio (1889), oil on canvas, 83 x 113.5 cm., Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Attributes of the Studio (1889), oil on canvas, 83 x 113.5 cm., Alte Pinakothek, Munich.jpg.webp)

The Assassination (1890), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Columbus Museum of Art [inspired by the death of Antoine B. Fualdès

The Assassination (1890), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Columbus Museum of Art [inspired by the death of Antoine B. Fualdès The Good Judges (1891), oil on panel, 38 x 46 cm., private collection

The Good Judges (1891), oil on panel, 38 x 46 cm., private collection

Still Life with Ray (1892) oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Still Life with Ray (1892) oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels The Dangerous Cooks (1896), oil on panel, 38 x 46 cm., private collection

The Dangerous Cooks (1896), oil on panel, 38 x 46 cm., private collection_-_Bloemen_en_groenten_001.jpg.webp) Flowers and Vegetables (1896), oil on canvas, 79 x 98 cm.; collection Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Flowers and Vegetables (1896), oil on canvas, 79 x 98 cm.; collection Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp The Great Judge (1898), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, private collection

The Great Judge (1898), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, private collection_oil_on_canvas%252C_117_x_82_cm.%252C_Menard_Art_Museum%252C_Komaki%252C_Japan.jpg.webp) Self-Portrait with Masks (1899), oil on canvas, 117 x 82 cm., Menard Art Museum, Komaki

Self-Portrait with Masks (1899), oil on canvas, 117 x 82 cm., Menard Art Museum, Komaki

Later work (1900–1949)

Still Life with Chinoiseries (c. 1906), oil on canvas, 85 × 105 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

Still Life with Chinoiseries (c. 1906), oil on canvas, 85 × 105 cm., Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

Fantastic Still Life (c. 1917), oil on canvas, 16 x 21.5 cm., Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna

Fantastic Still Life (c. 1917), oil on canvas, 16 x 21.5 cm., Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna Still Life with a Cabbage (1921), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Still Life with a Cabbage (1921), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands Girl with Masks or Eucharist (1921), oil on canvas, 57.2 × 52.5 cm., Städelsches Art Institute and Urban Gallery, Frankfurt

Girl with Masks or Eucharist (1921), oil on canvas, 57.2 × 52.5 cm., Städelsches Art Institute and Urban Gallery, Frankfurt_oil_on_canvas%252C_119_x_128_cm.jpg.webp) Finding of Moses (1924), oil on canvas, 119 x 128 cm., private collection

Finding of Moses (1924), oil on canvas, 119 x 128 cm., private collection%252C_oil_on_canvas.jpg.webp) The Vile Vivisectors (1925), oil on canvas, dimensions and collection unknown

The Vile Vivisectors (1925), oil on canvas, dimensions and collection unknown Ensor at the Harmonium (1933), oil on canvas, dimensions and collection unknown

Ensor at the Harmonium (1933), oil on canvas, dimensions and collection unknown

Printmaking

Ensor was a prolific and accomplished printmaker. He created 133 etchings and drypoints over the course of his career, with 86 of them made between 1886 and 1891 during the height of Ensor's most creative period.[22] Ensor himself recognized that the prints were a key part of his artistic legacy, stating in a letter to Albert Croquez in 1934: "Yes, my intention is to go on working for a long time yet so that generations to come may hear me. My intention is to survive, and I think of the solid copper plate, the unalterable ink, easy reproduction, faithful prints, and I adopt etching as a means of expression."[23]

In 1889, Ensor created two highly political etchings. The first, titled Doctrinal Nourishment [or Alimentation Doctrinaire], depicts key figures in Belgium—a bishop, the king, etc.—defecating on the masses of Belgium. The second, titled Belgium in the XIXth Century or King Dindon, depicts King Leopold II watching as military figures violently quell a protest. These prints are very rare today because Ensor attempted to remove them from circulation after being named Baron and many others were lost during the war.[24]

_etching%252C_25_x_19_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) The Cathedral (1886) etching, 25 x 19 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

The Cathedral (1886) etching, 25 x 19 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_drypoint%252C_24_x_18.1_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Ernest Rousseau (1887) drypoint, 24 x 18.1 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Ernest Rousseau (1887) drypoint, 24 x 18.1 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_drypoint%252C_13.9_x_9.2_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Boulevard Anspach (1888) drypoint, 13.9 x 9.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Boulevard Anspach (1888) drypoint, 13.9 x 9.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_etching%252C_13.8_x_17.8_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Country Fair Near a Windmill (1889) etching, 13.8 x 17.8 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Country Fair Near a Windmill (1889) etching, 13.8 x 17.8 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_etching%252C_6.9_x_12.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) My Portrait in the Year 1960 (1888) etching, 6.9 x 12., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

My Portrait in the Year 1960 (1888) etching, 6.9 x 12., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_drypoint%252C_11.9_x_15.9_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Peculiar Insects (1888) drypoint, 11.9 x 15.9 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Peculiar Insects (1888) drypoint, 11.9 x 15.9 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_17.8_x_24.8_cm.%252C_Plantin-Moretus_Museum%252C_Antwerp.jpg.webp) Alimentation Doctrinaire (1889) etching, 17.8 x 24.8 cm., Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp

Alimentation Doctrinaire (1889) etching, 17.8 x 24.8 cm., Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp_etching%252C_10_x_12_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) King Pest (1895) etching, 10 x 12 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

King Pest (1895) etching, 10 x 12 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_11.8_x_15.8_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Demons Taunting Me (1895) etching, 11.8 x 15.8 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Demons Taunting Me (1895) etching, 11.8 x 15.8 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_etching_and_drypoint%252C_17.9_x_24.2_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Christ Tormented by Demons (1895) etching and drypoint, 17.9 x 24.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Christ Tormented by Demons (1895) etching and drypoint, 17.9 x 24.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_13.9_x_17.8_cm.%252C_etching_and_drypoint%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) The Devils Dzitts and Hihanox Lead Christ into Hell (1895) 13.9 x 17.8 cm., etching and drypoint, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

The Devils Dzitts and Hihanox Lead Christ into Hell (1895) 13.9 x 17.8 cm., etching and drypoint, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_etching%252C_24.1_x_18.2_cm.%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Ghent.jpg.webp) Death Pursuing Humanity (1896) etching, 24.1 x 18.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Death Pursuing Humanity (1896) etching, 24.1 x 18.2 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent_etching%252C_19.7_x_29.8_cm.%252C_Plantin-Moretus_Museum%252C_Antwerp.jpg.webp) Plague Below, Plague Above, Plague Everywhere (1904) etching, 19.7 x 29.8 cm., Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp

Plague Below, Plague Above, Plague Everywhere (1904) etching, 19.7 x 29.8 cm., Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp

The Seven Deadly Sins

_etching%252C_9_x_14_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Death Dominating the Deadly Sins (1904) etching, 9 x 14 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Death Dominating the Deadly Sins (1904) etching, 9 x 14 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_15_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Anger (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Anger (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_15_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Avarice (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Avarice (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_15_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Envy (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Envy (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_15_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Gluttony (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Gluttony (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_13.7_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Lust (1888) etching, 9.8 x 13.7 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Lust (1888) etching, 9.8 x 13.7 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_9.8_x_15_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Pride (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Pride (1904) etching, 9.8 x 15 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_etching%252C_10_x_14_cm.%252C_Royal_Library_of_Belgium%252C_Brussels.jpg.webp) Sloth (1902) etching, 10 x 14 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Sloth (1902) etching, 10 x 14 cm., Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Honour

- 1919: Commander of the Order of Leopold.[25]

Influence and legacy

Ensor is considered to be an innovator in 19th-century art. Although he stood apart from other artists of his time, he significantly influenced such 20th-century artists as Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, George Grosz, Alfred Kubin, Wols, Felix Nussbaum,[26] and other expressionist and surrealist painters of the 20th century. As Los Angeles County Museum of Art CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan has explained: "James Ensor's signature style – his radical distortion of form, his ambiguous space, his riotous color, his muddled surfaces, and his proclivity for the bizarre – both anticipated and influenced modernist movements from symbolism and German expressionism to dada and surrealism."[27]

Ensor's works are in many public collections, notably the Modern Art Museum of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, and Mu.ZEE in Ostend. Major works by Ensor are also in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne. A collection of his letters is held in the Contemporary Art Archives of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels.[28] The Ensor collections of the Flemish fine art museums can all be seen at the James Ensor Online Museum.[29]

Ensor has been paid homage by contemporary painters[30] and artists in other media. The Belgian artist Pierre Alechinsky (b. 1927) and noted member of COBRA, painted The Tomb of Ensor (1961) in homage to Ensor, which is now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.[31] He is the subject of a song, "Meet James Ensor",[32] recorded in 1994 by the alternative rock duo They Might Be Giants. The 1996 Belgian movie, Camping Cosmos, was inspired by drawings of James Ensor, in particular Carnaval sur la plage (1887), La mort poursuivant le troupeau des humains (1896), and Le bal fantastique (1889). The film's director, Jan Bucquoy, is also the creator of a comic Le Bal du Rat mort[33] inspired by Ensor.

An exhibition of approximately 120 works by James Ensor was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 2009, and then at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, October 2009 – February 2010. The Getty mounted a similar exhibition June–September 2014.[34] The Art Institute of Chicago exhibited Ensor's 1887 masterpiece The Temptation of St. Anthony from November 2014 through January 2015, along with other important paintings and etchings.[35] From October 2016 through January 2017, the Royal Academy of Arts in London hosted a major exhibition of Ensor's paintings and etchings, curated by the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans.[36] The black artist Kara Walker painted a controversial work, "Christ's Entry into Journalism", inspired by Ensor in 2017.[37]

The yearly philanthropic "Bal du Rat mort" (Dead Rat Ball) in Ostend continues a tradition begun by Ensor and his friends in 1898.

In the movie Halloween (1978), a poster of one of Ensor's self-portraits appears on the wall of a room in Laurie Strode's (Jamie Lee Curtis) home.

References

- Citations

- "James Ensor". Netherlands Institute of Art (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Farmer 1976, p. 7

- "Info – Ensor Advisory Committee". Jamesensor.org. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- Becks-Malorny 2000, pp. 12–16

- Ensor et al. 2005, p. 21

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 94

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 10

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 95

- Swinbourne 2009

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 91

- Becks-Malorny 2000, pp. 91–92

- van Gindertael 1975, p. 114

- Arnason & Kalb 2004, p. 95

- Farmer 1976, p. 32

- J. Paul Getty Museum. Christ's Entry into Brussels in 1889. Archived 6 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 48

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 43

- Janssens, 1978, p. 89-90

- Becks-Malorny 2000, pp. 87–88

- Farmer, 1976, p. 31

- "Janssens, 1978, p. 91"

- Swinbourne 2009, p. 20

- Taevernier 1999, p. 8

- Taevernier 1999, pp. 199–209

- Royal Decree of H.M. King Albert I on 14 November 1919.

- Becks-Malorny 2000, p. 92

- Papanikolas, Theresa (2008). Doctrinal Nourishment: Art and Anarchism in the Time of James Ensor. Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-87587-199-8.

- "La Documentation". The Contemporary Art Archives. 24 December 2004. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "jamesensor.eu". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Mohammed, Nisha. American fundamentalists: Christ's entry into Washington in 2008. An interview with Joel Pelletier. Archived 22 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Rutherford Institute, 5 July 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- "Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: Pierre Alechinsky, The Tomb of Ensor". Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "Meet James Ensor" on This Might Be A Wiki

- Flemish newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws, 5 October 1981, Marc Wilmet: "Jan Bucquoy laureaat van het stripverhaal".

- "James Ensor's massive menace, minute malign fantasies on display at the Getty | Off-Ramp | 89.3 KPCC". scpr.org. 16 June 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "Temptation: The Demons of James Ensor". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Intrigue: James Ensor by Luc Tuymans | Exhibition". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- von Arx, Arabella Hutter (2 November 2017). "The Redemption of Art Through Disfigurement and Slaughter".

- Works cited

- Arnason, H. Harvard; Kalb, Peter (2004). History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 978-0-13-184069-0.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulrike (2000). James Ensor. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5858-7.

- Ensor, James; Pfeiffer, Ingrid; Hollein, Max; Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (2005). James Ensor. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz. ISBN 978-3-7757-1702-1.

- Farmer, John David (1976). Ensor. New York: George Braziller. OCLC 462494050.

- Swinbourne, Anne (2009). James Ensor. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978-0-87070-752-0.

- Taevernier, Auguste (1999). James Ensor. Belgium: Pandora/Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon. ISBN 90-5325-135-9.

- van Gindertael, Roger (1975). Ensor. Boston: New York Graphic Society Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8212-0649-2.

- Janssens, Jacques (1978). James Ensor. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-517-53284-0.

- Further reading

- Berko, Patrick & Viviane (1981). "Dictionary of Belgian painters born between 1750 & 1875", Knokke 1981, p. 272–274.

- Janssens, Jacques (1978). James Ensor. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

- Tricot, Xavier (1994). Ensoriana. Antwerp: Pandora.

- Tricot, Xavier (2009). James Ensor, Life and work. Catalogue raisonné of his paintings. Ostfildern: HatjeCantz.

- Tricot, Xavier (2010). James Ensor. The complete prints. Roeselare: Deceuninck.

External links

![]() Media related to Paintings by James Ensor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings by James Ensor at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by or about James Ensor at Internet Archive

- James Ensor Online Museum

- James Ensor Archief – Publications by or with the cooperation of Patrick Florizoone

- The Royal Museums' Modern Art Collection: 19th-century symbolism, with Ensor's Skeletons fighting for a smoked herring

- Exhibition at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp: "Ensor and the Moderns"

- The Getty Museum: James Ensor

- James Ensor: The Temptation of Saint Anthony digital exhibition catalogue

- Flemish Art Collection: James Ensor, Graphic Artist Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Goya, Redon, Ensor Grotesque paintings and drawings" 2009 Special Exhibition at KMSKA

- 2009 Ensor show at Museum of Modern Art, NYC

- Sanford Schwartz, "Mysteries of Ensor," New York Review of Books, 24 September 2009.