Iru Malargal

Iru Malargal (transl. Two Flowers) is a 1967 Indian Tamil-language romantic drama film directed by A. C. Tirulogchander. The film stars Sivaji Ganesan, Padmini and K. R. Vijaya, with Nagesh, S. A. Ashokan, V. Nagayya, Manorama and Roja Ramani in supporting roles. It revolves around a man who faces upheavals in his life as he is caught between his lady-love and his devoted wife.

| Iru Malargal | |

|---|---|

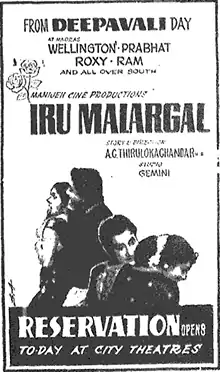

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | A. C. Tirulogchander |

| Screenplay by | Aaroor Dass (dialogues) |

| Story by | A. C. Tirulogchander |

| Produced by | Thambu |

| Starring | Sivaji Ganesan Padmini K. R. Vijaya |

| Cinematography | Thambu |

| Edited by | B. Kanthasamy |

| Music by | M. S. Viswanathan |

Production company | Manijeh Cine Productions |

Release date |

|

| Country | India |

| Language | Tamil |

Iru Malargal was released on 1 November 1967, Diwali day. The film became a commercial success, running for over 100 days in theatres, and won two awards at the Tamil Nadu State Film Awards: Best Actress for Vijaya and Best Story Writer for Tirulogchander.

Plot

Sundar and Uma are classmates who fight often. Sundar, however, is very much in love with Uma, and when they perform in a dance drama competition at Madurai, and later move on to Kodaikanal, he expresses this love. Uma asks him to climb up a peak so that she will consider him as a suitor. Sundar suffers from acrophobia and almost falls while climbing, at which point Uma accepts his love.

Sundar's cousin Shanti, who lives with his family and takes care of the entire household, is fond of him and wishes to marry him. Sundar's father Sivasamy also wants this marriage to take place. When Shanti discovers the love between Sundar and Uma, however, she changes her mind. Sivasamy asks Sundar to marry Shanti, but he refuses, revealing that he is in love with Uma. Furious, Sivasamy begins looking for another bridegroom for Shanti.

Meanwhile, Uma goes to seek permission to marry Sundar from her brother, who is her only living relative. She tells Sundar that she will send him a letter on a particular date (10 October). When Uma's letter informs him that she has decided to marry another person because she is not willing to go against her brother's wishes, an emotionally distraught Sundar becomes bedridden. In truth, Uma's brother and sister-in-law died in an accident. She decided to renounce her love to take care of their children, and lied to Sundar so that he would not come after her.

While taking care of the dejected Sundar, Shanti is confronted by her bridegroom who accuses her of having a relationship with Sundar. When Sundar realises how much his father and his cousin have suffered because of him, he decides to marry Shanti.

Years later, Sundar has become a successful businessman living in Kodaikanal with Shanti and their daughter Geetha; Sivasamy is long dead. Uma joins Geetha's school and becomes her teacher. When Geetha enthusiastically tells her mother about Uma, Shanti wants Uma to take tuition for Geetha; Uma accepts. She is shocked to learn that Geetha is Sundar's child when they accidentally meet along the road. Sundar goes to Uma's home, where they have a conversation about the past. Hearing this, Geetha realises that her father was once in love with her teacher.

Shanti learns of Sundar's relationship with Uma. Not wanting to cause Sundar and Shanti to separate, Uma gives a letter to the school principal Sundaravathanam, asking him to take care of her brother's children if something happens to her, and goes to a cliff to meet Sundar. She asks Sundar if will he come with her leaving everything behind if she calls him. Sundar replies that he could leave anything except his wife and child. This is the answer Uma wants, having decided that, if Sundar talked about leaving Shanti and Geetha, she would throw herself from the cliff. At the same time, Shanti concludes that Uma and Sundar should be united, and decides to commit suicide, Uma and Sundar stop her, with Uma telling her everything that happened between her and Sundar was in the past. Uma also tells Sundar and Shanti that she does not want to cause further problems for them and leaves.

Cast

- Sivaji Ganesan as Sundar

- Padmini as Uma

- K. R. Vijaya as Shanthi

- V. Nagayya as Sivasamy

- S. A. Ashokan as Balu

- Nagesh as Sundaravathanam

- Manorama as Poongothai

- Roja Ramani as Geetha

- Master Sridhar as Suresh

- Pasi Narayanan as college classmate

- Madhavi as Sudha

Production

The story of Iru Malargal was written by A. C. Tirulokachandar who also directed,[1] and produced by Thambu under Manijeh Cine Productions.[2] The dialogues were written by Aaroor Dass. Cinematography was handled by Thambu, and editing by B. Kanthasamy.[1] Tirulokachandar's name was spelt "Tirulogchander" in the credits.[3]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was composed by M. S. Viswanathan, while Vaali penned the lyrics,[4][5] replacing Viswanathan's usual associate Kannadasan.[6] The song "Maharaja Oru Maharani" was the first in Tamil to feature ventriloquism before it was used on a larger scale in Avargal 10 years later.[7] It marked the debut of Shoba Chandrasekhar as a playback singer.[8] Vaali considered the number "Madhavi Ponmayilal" as one among his "personal favourites".[9] The song is set in Kharaharapriya raga.[10][11] N. Sathiya Moorthy Rediff.com named it as one of Vaali's "most memorable songs".[12]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Kadavul Thantha" | L. R. Eswari, P. Susheela | |

| 2. | "Maharaja Oru Maharani" | Sadan, Shoba, T. M. Soundararajan | |

| 3. | "Mannikka Vendugiren" | T. M. Soundararajan, P. Susheela | |

| 4. | "Madhavi Pon Mayilaal" | T. M. Soundararajan | |

| 5. | "Velli Mani" | P. Susheela | |

| 6. | "Annamita Kaigaluku" | P. Susheela |

Release and reception

Iru Malargal was released on 1 November 1967,[13] Diwali day. Despite facing competition from another Sivaji Ganesan film Ooty Varai Uravu, released on the same day,[14][15] it emerged a commercial success, running for over 100 days in theatres.[16] Kalki lauded the performances of Ganesan, Padmini, Vijaya and Nagayya, but felt the screenplay could have been more concise and certain songs removed.[17] At the Tamil Nadu State Film Awards, Vijaya won for Best Actress, and Tirulokchandar won for Best Story Writer.[7]

References

- Cowie & Elley 1977, p. 265.

- "1967–இரு மலர்கள்- மணிஜே சினி புரொ.(100 நாள்)" [1967-Iru Malargal- Manijeh Cine Pro.(100 days)]. Lakshman Sruthi (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Rangarajan, Malathi (18 June 2016). "A director who stood tall". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Aalayamani – Iru Malargal Tamil Film LP Vinyl Record by M S Viswanathan". Mossymart. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Iru Malargal (1967)". Raaga.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Rangarajan, Malathi (9 July 2004). "Memorable evening in many ways". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2005. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- "செலுலாய்ட் சோழன் – 112 – சுதாங்கன்" [Celluloid King – 112 – Sudhangan]. Dinamalar (in Tamil). Nellai. 7 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Ashok Kumar, S. R. (13 April 2006). "A celebrity in her own right". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Ashok Kumar, S. R. (1 February 2007). "A lyrical journey across four generations in cinema". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Mani, Charulatha (13 April 2012). "A Raga's Journey — Kingly Kharaharapriya". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Sundararaman 2007, p. 140.

- Sathiya Moorthy, N. (22 July 2013). "Remembering Vaali". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- "Iru Malargal". The Indian Express. 1 November 1967. p. 3. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- Jeshi, K. (1 November 2013). "Released on Deepavali". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- நரசிம்மன், டி.ஏ. (26 October 2018). "சி(ரி)த்ராலயா 39: ஊட்டி வரை லூட்டி". Hindu Tamil Thisai (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Ganesan & Narayana Swamy 2007, p. 242.

- "இரு மலர்கள்". Kalki (in Tamil). 12 November 1967. p. 14. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

Bibliography

- Cowie, Peter; Elley, Derek (1977). World Filmography: 1967. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 0-498-01565-3.

- Ganesan, Sivaji; Narayana Swamy, T. S. (2007) [2002]. Autobiography of an Actor: Sivaji Ganesan, October 1928 – July 2001. Sivaji Prabhu Charities Trust. OCLC 297212002.

- Sundararaman (2007) [2005]. Raga Chintamani: A Guide to Carnatic Ragas Through Tamil Film Music (2nd ed.). Pichhamal Chintamani. OCLC 295034757.

External links

- Iru Malargal at IMDb