International healthcare accreditation

Due to the near-universal desire for safe and good quality healthcare, there is a growing interest in international healthcare accreditation.[1] Providing healthcare, especially of an adequate standard, is a complex and challenging process. Healthcare is a vital and emotive issue—its importance pervades all aspects of societies, and it has medical, social, political, ethical, business, and financial ramifications. In any part of the world healthcare services can be provided either by the public sector or by the private sector, or by a combination of both, and the site of delivery of healthcare can be located in hospitals or be accessed through practitioners working in the community, such as general medical practitioners and dental surgeons.

This is occurring in most parts of the developed world in a setting in which people are expressing ever-greater expectations of hospitals and healthcare services. This trend is especially strong where socialised medical systems exist. For example, in the European Union "... patients have ever-greater expectations of what health systems ought to deliver," although there has been a "... continuous rise in costs of services determined by scientific and technological innovation."[2] And in one particular EU member state, the United Kingdom, "... People are going to increase demand and they have also got an increased expectation of what the NHS can deliver."[3] The USA manifests some differences here, and is an unusual and distinct oddity among developed Western countries. In 2007, 45.7 million of the overall US population (i.e. 15.3%) had no health insurance whatsoever[4] yet in 2007 the USA spent nearly $2.3 trillion on healthcare, or 16% of the country's gross domestic product, more than twice as much per capita as the OECD average.[5] Because of this, some US citizens are having to look outside of their country to find affordable healthcare, through the medium of medical tourism, also known as "Global Healthcare" (see below).

Apart from using hospitals and healthcare services to regain their health if it has become impaired, or to prevent ill health occurring in the first place, people the world over may also use them for a wide variety of other services, for example “improving upon nature” (e.g. cosmetic surgery, gender reassignment surgery[6] or acquiring help to overcome difficulties with becoming a parent (e.g. infertility treatment).[7]

Healthcare and hospital accreditation

Fundamentally healthcare and hospital accreditation is about improving how care is delivered to patients and the quality of the care they receive. Accreditation has been defined as "A self-assessment and external peer assessment process used by health care organisations to accurately assess their level of performance in relation to established standards and to implement ways to continuously improve" [8] Interest in hospital accreditation ascends as far as the World Health Organization (see external links). Accreditation is one important component in patient safety. However, there is limited and contested evidence supporting the effectiveness of accreditation programs.[9]

In the USA in the early 20th century, there was concern over how to best create an appropriate environment in which clinicians could work. Standards to improve the control of the hospital environment were thus generated, and these subsequently grew into accreditation schemes with the remit to facilitate and improve organisational development. Part of the process is not only about assessing quality, but also about promoting and improving quality. Similar accreditation schemes were soon developed elsewhere in the world.

In countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, sophisticated accreditation groups have grown up to survey hospitals (and, in some cases, healthcare in the community). Furthermore, other accreditation groups have been set up with openly declared remits to look after just one particular area of healthcare, such as laboratory medicine or psychiatric services or sexual health.

Accreditation systems are structured so as to provide objective measures for the external evaluation of quality and quality management. Accreditation schemes should ideally focus primarily on the patient and their pathway through the healthcare system – this includes how they access care, how they are cared for after discharge from hospital, and the quality of the services provided for them. At the heart of these schemes is a list of standards which, ideally, serve to assess evaluate in a systematic and comprehensive way the standards of professional performance in a hospital. This includes not only hand-on patient care but also training and education of staff, credentials, clinical governance and audit, research activity, ethical standards etc. The standards can also be used internally by hospitals to develop and improve their quality standards and quality management. Some international accreditation schemes believe that the standards applied should be fixed and are non-negotiable, while others operate a system of negotiation over standards - however, whatever approach is taken the every aspect of the process should be evidence-based.

International standardization groups also exist, but it must be pointed out that the mere achieving of set standards is not the only factor involved in quality accreditation - there is also the significant matter of the incorporating into participating hospitals systems of self-examination, problem solving and self-improvement, and hence there is more to accreditation than following some sort of overall "standardization" process.

As governments and the general public have increasingly come to demand more and more openness about health care and its delivery, including and especially hospital quality and safety and the clinical performance of doctors, and these accreditation systems have generally adapted to fulfill this extended role.

However, accreditation should ideally be independent of governmental control, and accreditation groups should assess hospitals “holistically”, and not just some isolated facet of the hospital’s activities or services such as the laboratories, pharmacy services, infection control, financial health or information technology services (indeed, partial accreditation of this type should be publicly acknowledged as such by both the accreditation scheme and the hospital). The best accreditation schemes also assess academic and intellectual activity (such as teaching and research) within those hospitals that they survey (see later) and have a clear and declared interest in medical ethics.

In some parts of the world, accessing healthcare can be very expensive, even prohibitively so. While some countries have elected to provide comprehensive healthcare services for all of their populations, others appear to be satisfied with leaving portions of their population without access to healthcare. When it comes to who pays the bills for healthcare, it may be the government or it may be the individual (sometimes either by direct payment, and sometimes through employer-run schemes, insurance companies etc.), or a combination of both. However, healthcare can never be truly “free” – someone somewhere will always have to pay, and the payer will always want the best value for money possible. "Affordability" of healthcare can be the insurmountable hurdle for some people. Value for money is hence another factor in assessing the true quality of healthcare.

Background

A number of larger countries engage in hospital accreditation that is provided internally. Taking the USA as an example, numerous groups provide accreditation for internal healthcare organizations, including the AAAHC Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care, doing business internationally as "Acreditas Global", Community Health Accreditation Program (CHAP), the Joint Commission, TJC, Accreditation Commission for Health Care, Inc. (ACHC), the "Exemplary Provider Program" of The Compliance Team, American Accreditation Commission International (AACI), and the Healthcare Quality Association on Accreditation (HQAA).

Other countries have looked towards accessing the services of the major international healthcare accreditation groups based in other countries to assess their healthcare services. There are many reasons for this, including cost, a desire to improve healthcare quality for one’s own citizens (good governance is at the basis of all high-quality healthcare), or a desire to market one’s healthcare services to “medical tourists”. Some hospitals pursue international healthcare accreditation as a de facto form of advertising.

In response to this marketing opportunity, some national accreditation groups have expanded internationally, and gone on to survey and accredit hospitals outside of their own national borders, providing "international healthcare accreditation".

This process of accreditation has been made increasingly complicated by the fact that in many parts of the world, people are choosing to cross international borders to access healthcare, a phenomenon known as “medical tourism” or "Global Healthcare". Medical tourism/Global Healthcare is key issue in international healthcare accreditation. It is becoming increasingly important as millions of (especially) Europeans and Americans seek healthcare overseas outside of their own countries for a variety of reasons, including and especially affordability. It represents a growing multibillion-euro/dollar/pound business of increasing importance to the economies of many countries, such as Singapore, Thailand, India, Hong Kong, Malaysia and the Philippines. The importance of medical tourism/Global Healthcare to the economy of developing countries is increasingly the subject of academic study. , and this synergy has a clear "knock-on" effect for those organizations based within the developed world who are seeking to develop the medical tourism/Global Healthcare market.

Reasons why patients are seeking out medical tourism/Global Healthcare options are manifold;

- (a) healthcare may be too expensive at home

- (b) waiting lists may be too long

- (c) patients wish to access treatments not available at home (e.g. stem cell therapy, termination of pregnancy, unlicensed medications, gender re-assignment surgery)

- (d) patients wish for greater confidentiality than may be feasible at home (e.g. HIV/AIDS treatment, infertility treatment, gender re-assignment surgery, face lifts)

- Other new challenges include new medical developments which are not universally accessible, the emergence of the so-called “superbugs” (e.g. MRSA, VRSA, VRE>Clostridium difficile, ESBL-producing E. coli), problems with the blood transfusion supply (e.g. Chaga's disease in the USA, HIV, HTLV-1 etc.), and the social imponderables such as war, political change and natural disasters. Any of these factors may lead to a loss of public confidence in healthcare services, and a desire to seek out healthcare overseas. The environmental and political situation will constantly vary throughout the world, and this will need to be factored into the equations.

The following quote, from the website of Partners Harvard Medical International, crystallizes the increasing relevance of international health care accreditation and its growing commercial importance, particularly in relation to medical tourism/global healthcare. "In competitive health care markets where patients have an increasing array of choices, quality is the most important differentiator for organizations striving for sustainability and both national and regional leadership. International accreditation has become a powerful indicator of a health care organization’s commitment to high-quality care and patient safety.[10]" Reflecting this, much of the discussion on medical tourism blog sites reflects the increasing importance of international healthcare and hospital accreditation to this industry

Consumers

How does an individual contemplating becoming a medical tourist ensure that the overseas healthcare they are planning to access is as safe as possible and is of adequate quality? For sure, it is not simply a matter of looking at hospital buildings and at mattresses, and it is certainly not just an issue of looking only at the prices charged. While architecturally pleasing rooms and easier access to satellite television and the internet may improve personal comfort, and a bargain basement price may help the wallet, what is often more important may include such issues as:

- the standards of governance in the hospital or clinic

- the healthcare providing establishment’s commitment to self-improvement, and to learn positively from errors

- the overall medical ethical standards operating within the organization

- the clinical staff’s ethical standards and their personal and collective commitment to caring for patients and the wider community

- the quality of the clinical staff, including their background educational attainment and training, and evidence of continuing professional development by those staff

- the quality and ethical standards of the management and their personal and collective commitment to caring for patients and the wider community

- the clinical track record of the hospital or clinic

- the infection control track record of the hospital or clinic

- the hospital may be located in a country where the environment and climate may bring a patient into contact with infectious and/or tropical diseases that are unfamiliar to them

- evidence of a robust, just and fair system to deal with complaints made by patients when things go wrong, as they inevitably will from time to time, and where appropriate to compensate the injured party in a fair and reasonable way

The above list is not exhaustive, but it represents a good start. Also, the intending medical tourist should check whether or not a hospital is wholly accredited by an international accreditation group, or if it is only partly accredited (e.g. for infection control), the latter being less inclined to create confidence in a potential consumer.

How does the person in the street access this type of quality information? This can be very difficult. Accreditation schemes well-recognised as providing services in the international healthcare accreditation field include:

- Joint Commission International (JCI) (based in the United States)

- Trent Accreditation Scheme (based in UK-Europe) The former Trent Scheme (which ended in 2010) was the first scheme to accredit a hospital in Asia, in Hong Kong in 2000

The different accreditation schemes vary in approach, quality, size, intent, sourcing of surveyors and the skill of their marketing. They also vary in terms of how much they charge hospitals and healthcare institutions for their services. They all have web sites.

Umbrella organizations

The International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) is an umbrella organisation for such organisations providing international healthcare accreditation.[11] Its offices are based in the Republic of Ireland. ISQua is a small non-profit limited company with members in over 70 countries. ISQua works to provide services to guide health professionals, providers, researchers, agencies, policy makers and consumers, to achieve excellence in healthcare delivery to all people, and to continuously improve the quality and safety of care. ISQua does not actually survey or accredit hospitals or clinics itself.

The United Kingdom Accreditation Forum, or UKAF, is a UK-based umbrella organisation for organisations providing healthcare accreditation.[12] Its offices are based in London. Like ISQua, UKAF does not actually survey and accredit hospitals itself. India becomes 12th nation to join ISQua.

Accreditation services

If a hospital or clinic simply wishes to improve its services to patients wherever those patients come from (locally or from further afield), or wishes to attract medical tourists, how do they choose whom to go to when contemplating accessing external peer review by an accreditation group such as those listed above. No one healthcare system has a monopoly of excellence and no one provider country or scheme can claim to be the total arbiter of quality. The same is true of healthcare accreditation schemes.

For example, some countries, such as the USA, perform very poorly when it comes to providing anything close to universal access to healthcare of adequate quality to the population living within their own borders. Others, such as the United Kingdom and Australia, have created state-funded systems which provide everything without the assistance of the private sector.

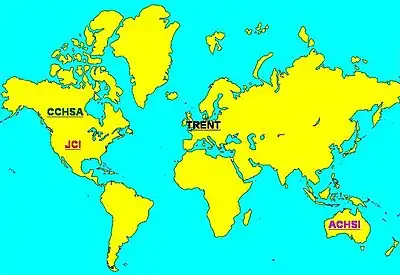

Different holistic accreditation schemes are sourced out of different parts of the world, for example in hospitals there is (see map):

- ACSA International out of Spain: partnership with IBES - Brazilian Healthcare Excellence Institute.

- Joint Commission International (JCI) out of the USA[13]

- Accreditation Canada [14]

- QHA Trent out of the United Kingdom[15]

- Australian Council on Health Care Standards International in Australia[16]

No single international accreditation scheme enjoys exclusive rights to be seen as an overall worldwide-relevant scheme. Some hospitals seek multiple accreditations to increase their credibility in different parts of the world.

Other fields of accreditation pertain to general medical practices ("GP" or Family Medicine) is some westernized countries. GP accreditation services, such as the Royal College of General Practitioners (RGCP)[17] in the United Kingdom, and Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited (AGPAL)[18] in Australia provide accreditation services for these practices. The cost of such accreditation varies enormously[19] and precise data are scarce; in the case of the Joint Commission International, JCI, costs can be substantial. Variance in cost is based on the country, size and operations of an organization.[20][21]

For hospitals, ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is often mistakenly considered to be an international healthcare accreditation scheme. However it is not.

See also

- Accreditation

- Hospital accreditation

- Evidence-based medicine

- Health tourism provider

- Health insurance

- Hospital, Lists of hospitals

- List of international healthcare accreditation organizations

- Medical tourism

- Patient safety

- Patient safety organization

- Medical ethics

- International SOS

- International Organization for Standardization

- United Kingdom Accreditation Forum

References

- Lovern E. (Nov 13, 2000) "Accreditation gains attention." Modern Healthcare 30(47):46.

- Office for International Public Health and Social Affairs. "Contribution to the Reflection Process for a New EU Health Strategy." Venice Italy: Regional Health and Social Department.

- UK Parliament Select Committee on Health (9 February 2006). Minutes of Evidence. Examination of Witnesses Bernie Hurn and Michael Hall (Questions 520 - 530)].

- Sherman, A., R. Greenstein, and S. Parrott (August 26, 2008). "Poverty and Share of Americans Without Healthcare Were Higher in 2007...". Washington: Centre for Budget and Policy Priorities.

- "Health care: Bill of Health". The Economist. 26 June 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- BBC News https://web.archive.org/web/20070817100337/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/newsnight/4115535.stm. Archived from the original on 2007-08-17.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Multiple births and fertility treatment". Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/323/7310/443 .

- Hinchcliff, R; Greenfield, D; Moldovan, M; Westbrook, J.I; Pawsey, M; Mumford, V; Braithwaite, J (4 October 2012). "Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature". BMJ Quality and Safety. 21 (12): 979–91. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000852. PMID 23038406. S2CID 40661152.

- "Making Quality the Competitive Edge". 29 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010.

- "International Society for Quality in Health Care". ISQua.

- "United Kingdom Accreditation Forum". UKAF.

- "Joint Commission International". JCI.

- "Accreditation Canada". Accreditation Canada.

- "QHA Trent". GQH.

- "Australian Council on Health Care Standards International". ACHS.

- "Roayal College of General Practitioners". RCGP.

- "Home". agpal.com.au.

- "India Accreditation a Must". IMTJ Online. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- "India Accreditation a Must". Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- "JCI How much do they charge hospitals". Joint Commission. 10 February 2008.

External links

- Editorial. Arce H. Hospital accreditation as a means of achieving international quality standards in health. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 10, Number 6, December 1998, pp. 469–472(4).

- Role of WHO in hospital accreditation. © 2004 WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean

- Partners Harvard Medical International: Making Quality the Competitive Edge.

- Raik E. Aged Care Accreditation in Australia. BMJ rapid response, 7 November 2001.

- Robinson R. Book Review - "Accreditation: Protecting the Professional or the Consumer?" BMJ 1995;311:818-819.

- Rawlins R. Hospital accreditation is important. BMJ 2001;322:674