Indole alkaloid

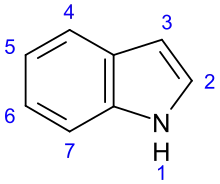

Indole alkaloids are a class of alkaloids containing a structural moiety of indole; many indole alkaloids also include isoprene groups and are thus called terpene indole or secologanin tryptamine alkaloids. Containing more than 4100 known different compounds, it is one of the largest classes of alkaloids.[1] Many of them possess significant physiological activity and some of them are used in medicine. The amino acid tryptophan is the biochemical precursor of indole alkaloids.[2]

History

The action of some indole alkaloids has been known for ages. Aztecs used the psilocybin mushrooms which contain alkaloids psilocybin and psilocin. The flowering plant Rauvolfia serpentina which contains reserpine was a common medicine in India around 1000 BC. Africans used the roots of the perennial rainforest shrub Iboga, which contain ibogaine, as a stimulant. An infusion of Calabar bean seeds was given to people accused of crime in Nigeria: its rejection by stomach was regarded as a sign of innocence, otherwise, the person was killed via the action of physostigmine, which is present in the plant and which causes paralysis of the heart and lungs.[3]

Consumption of rye and related cereals contaminated with the fungus Claviceps purpurea causes ergot poisoning and ergotism in humans and other mammals. The relationship between ergot and ergotism was established only in 1717, and the alkaloid ergotamine, one of the main active ingredients of ergot, was isolated in 1918.[4]

The first indole alkaloid, strychnine, was isolated by Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou in 1818 from the plants of the genus Strychnos. The correct structural formula of strychnine was determined only in 1947, although the presence of the indole nucleus in the structure of strychnine was established somewhat earlier.[5][6] Indole itself was first obtained by Adolf von Baeyer in 1866 while decomposing Indigo.[7]

Classification

Indole alkaloids are distinguished depending on their biosynthesis. The two types of indole alkaloids are isoprenoids and non-isoprenoids. The latter include terpenoid structural elements, synthesized by living organisms from dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and/or isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP):[8]

- Non-isoprenoid:

- Simple derivatives of indole

- Simple derivatives of β-carboline

- Pyrroloindole alkaloids

- Indole-3-carbinol

- Indole-3-acetic acid

- Tryptamines

- Carbazoles

- Isoprenoid:

- hemiterpenoids: ergot alkaloids

- monoterpenoids.

- Strictosidine

- Catharanthine

- Yohimbine

- Vinca

- Strychnine

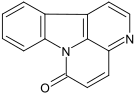

- Ellipticine

There are also purely structural classifications based on the presence of carbazole, β-carboline or other units in the carbon skeleton of the alkaloid molecule.[9] Some 200 dimeric indole alkaloids are known with two indole groups.[10]

Non-isoprenoid indole alkaloids

The number of known non-isoprenoid indole alkaloids is small compared to the number of indole alkaloids.[2]

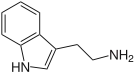

Simple indole derivatives

One of the simplest and yet widespread indole derivatives are the biogenic amines tryptamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin).[11] Although their assignment to the alkaloid is not universally accepted,[12] they are both found in plants and animals.[13] The tryptamine skeleton is part of the vast majority of indole alkaloids.[14] For example, N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), psilocin and its phosphorylated psilocybin are the simplest derivatives of tryptamine.[13] Some simple indole alkaloids do not contain tryptamine, such as gramine and glycozoline (the latter is a derivative of carbazole).[15] Camalexin is a simple indole alkaloid produced by the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, often used as a model for plant biology.[16]

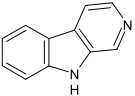

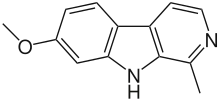

Simple derivatives of β-carboline

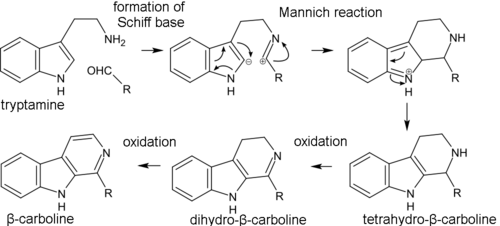

The prevalence of β-carboline alkaloids is associated with the ease of forming the β-carboline core from tryptamine in the intramolecular Mannich reaction. Simple (non-isoprenoid) β-carboline derivatives include harmine, harmaline, harmane[17] and a slightly more complex structure of canthinone.[18] Harmaline was first isolated in 1838 by Göbel[19] and harmine in 1848 by Fritzche.[20][21][22]

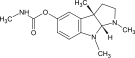

Pyrolo-indole alkaloids

Pyrolo-indole alkaloids form a relatively small group of tryptamine derivatives. They are produced by methylation of indole nucleus at position 3 and the subsequent nucleophilic addition at the carbon atom in positions 2 with the closure of the ethylamino group into a ring. A typical representative of this group is physostigmine,[23] which was isolated by Jobst and Hesse in 1864.[24][25]

Isoprenoid indole alkaloids

Isoprenoid indole alkaloids include residues of tryptophan or tryptamine and isoprenoid building blocks derived from the dimethylallyl pyrophosphate and isopentenyl pyrophosphate.[2]

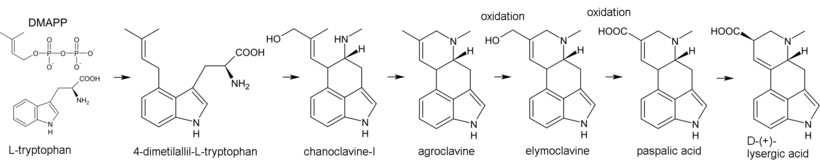

Ergot alkaloids

Ergot alkaloids are a class of hemiterpenoid indole alkaloids related to lysergic acid, which, in turn, is formed in a multistage reactions involving tryptophan and DMAPP. Many ergot alkaloids are amides of lysergic acid. The simplest such amide is ergine, and more complex can be distinguished into the following groups:[26][27]

- Water-soluble aminoalcohol derivatives, such as ergometrine and its isomer ergometrinine

- Water-insoluble polypeptide derivatives:

- Ergotamine group, including ergotamine, ergosine and their isomers

- Ergoxine groups, including ergostine, ergoptine, ergonine and their isomers

- Ergotoxine group, including ergocristine, α-ergocryptine, β-ergocryptine, ergocornine and their isomers.

Ergotinine, discovered in 1875, and ergotoxine (1906) were subsequently proven to be a mixture of several alkaloids. In pure form, the first ergot alkaloids, ergotamine and its isomer ergotaminine were isolated by Arthur Stoll in 1918.[27]

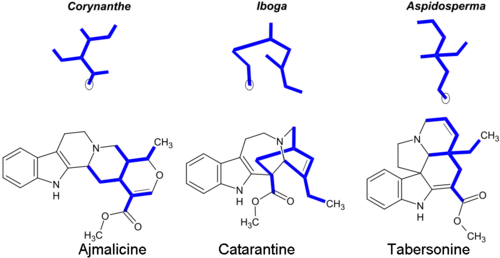

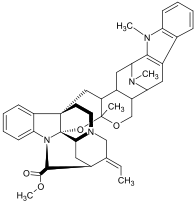

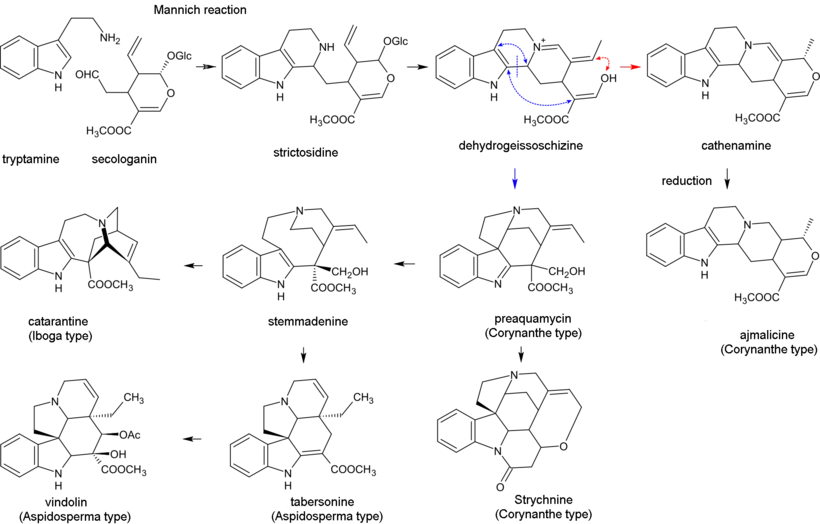

Monoterpenoid Indoles Alkaloids or Secologanin Tryptamine Alkaloids

Most monoterpenoid alkaloids include a 9 or 10 carbon fragment (bold in image) (originating from the secologanin), and the configuration allows grouping to Corynanthe, Iboga and Aspidosperma classes. The monoterpenoid part of their carbon skeletons are illustrated below on the example of alkaloids ajmalicine and catharanthine. The circled carbon atoms are missing in the alkaloids which contain the C9 fragment instead of C10.[14]

Corynanthe alkaloids include the unaltered skeleton of secologanin, which is modified in Iboga and Aspidosperma alkaloids.[28] Some representative monoterpenoid indole alkaloids:[5][29][30]

| Type | Number of carbon atoms in the monoterpenoid fragment | |

|---|---|---|

| C9 | C10 | |

| Corynanthe | Ajmaline, aquamycin, strychnine, brucine | Ajmalicine, yohimbine, reserpine, sarpagin, mitragynine |

| Iboga | Ibogaine, ibogamine | Voacangine, catharanthine |

| Aspidosperma | Eburnamin | Tabersonine, vindolin, vincamine |

There is also a small group of alkaloids present in the plant Aristotelia – about 30 compounds, the most important of which is peduncularine – which contain a monoterpenoid C10 part originating not from secologanin.[31]

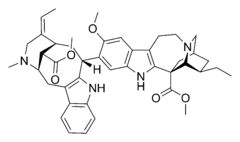

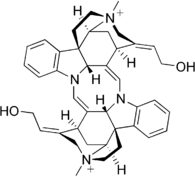

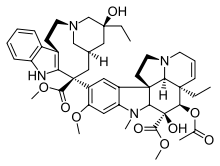

Bisindole alkaloids

Dimers of strictosidine derivatives, loosely called bisindoles but more complicated than that. More than 200 of dimeric indole alkaloids are known. They are produced in living organisms through dimerization of monomeric indole bases, in the following reactions:[32]

- Mannich reaction (voacamine)

- Michael reaction (villalstonine)

- Condensation of aldehydes with amines (toxiferine, calebassine)

- Oxidative coupling of tryptamines (calicantine);

- Splitting of the functional group of one of the monomers (vinblastine, vincristine).

|

|

|

|

| Voacamine | Villalstonine | Toxiferine | Vinblastine |

Apart from bisindole alkaloids, dimeric alkaloids exist which are formed via dimerization of the indole monomer with another type of alkaloid. An example is tubulosine consisting of indole and isoquinoline fragments.[33]

Distribution in nature

The plants that are rich in non-isoprenoid indole alkaloids include harmal (Peganum harmala), which contains harmane, harmine and harmaline, and Calabar bean (Physostigma venenosum) containing physostigmine.[34] Some members of the family Convolvulaceae, in particular Ipomoea violacea and Turbina corymbosa, contain ergolines and lysergamides.[35] Despite the considerable structural diversity, most of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids is localized in three families of dicotyledon plants: Apocynaceae (genera Alstonia, Aspidosperma, Rauvolfia and Catharanthus), Rubiaceae (Corynanthe) and Loganiaceae (Strychnos).[36][37]

Indole alkaloids are also present in fungi. For example, psilocybin mushrooms contains derivatives of tryptamine and Claviceps contains derivatives of lysergic acid.[34] The skin of many toad species of the genus Bufo contains a derivative of tryptamine, bufotenin, and the skin and venom of the species Bufo alvarius (Colorado River toad) contains 5-MeO-DMT.[38] Serotonin, which is an important neurotransmitter in mammals, can also be attributed to simple indole alkaloids.[39]

Physostigma venenosum "Calabar bean", source of physostigmine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants)

Physostigma venenosum "Calabar bean", source of physostigmine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants) Ipomoea violacea contains ergolines

Ipomoea violacea contains ergolines Strychnos toxifera, source of the paralysant alkaloid toxiferine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants)

Strychnos toxifera, source of the paralysant alkaloid toxiferine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants) Strychnos nux-vomica, principal source of the convulsant alkaloid strychnine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants)

Strychnos nux-vomica, principal source of the convulsant alkaloid strychnine (coloured plate from Köhler's Medicinal Plants)

_in_Hyderabad_W2_IMG_9005.jpg.webp) Alstonia macrophylla contains Corynanthe alkaloids

Alstonia macrophylla contains Corynanthe alkaloids.jpg.webp) Rauvolfia serpentina contains Corynanthe alkaloids

Rauvolfia serpentina contains Corynanthe alkaloids Catharanthus roseus contains monoterpenoid indole alkaloids

Catharanthus roseus contains monoterpenoid indole alkaloids Tabernaemontana divaricata contains indole alkaloids including catharanthine, conophylline, ibogamine, tabersonine and voacristine[40]

Tabernaemontana divaricata contains indole alkaloids including catharanthine, conophylline, ibogamine, tabersonine and voacristine[40]

Ergot contains ergolines

Ergot contains ergolines

Biosynthesis

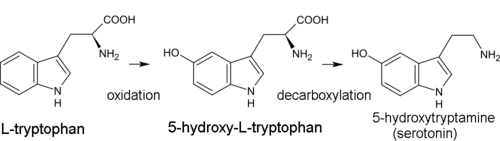

Biogenetic precursor of all indole alkaloids is the amino acid tryptophan. For most of them, the first synthesis step is decarboxylation of tryptophan to form tryptamine. Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is formed from tryptamine by methylation with the participation of coenzyme of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM). Psilocin is produced by spontaneous dephosphorylation of psilocybin.[41]

In the biosynthesis of serotonin, the intermediate product is not tryptamine but 5-hydroxytryptophan, which is in turn decarboxylated to form 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin).[13]

Biosynthesis of β-carboline alkaloids occurs through the formation of Schiff base from tryptamine and aldehyde (or keto acid) and subsequent intramolecular Mannich reaction, where the C(2) carbon atom of indole serves as a nucleophile. Then, the aromaticity is restored via the loss of a proton at the C(2) atom. The resulting tetrahydro-β-carboline skeleton then gradually oxidizes to dihydro-β-carboline and β-carboline. In the formation of simple β-carboline alkaloids, such as harmine and harmaline, pyruvic acid acts as the keto acid. In the synthesis of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids, secologanin plays the role of the aldehyde. Pirroloindole alkaloids are synthesized in living organisms in a similar way.[42]

Biosynthesis of ergot alkaloids begins with the alkylation of tryptophan by dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), where the carbon atom C(4) in the indole nucleus plays the role of the nucleophile. The resulting 4-dimethylallyl-L-tryptophan undergoes N-methylation. Further products of biosynthesis are chanoclavine-I and agroclavine – the latter is hydroxylated to elymoclavine, which in turn oxidizes into paspalic acid. In the process of allyl rearrangement, paspalic acid is converted to lysergic acid.[43]

Biosynthesis of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids begins with the Mannich reaction of tryptamine and secologanin; it yields strictosidine which is converted to 4,21-dehydrogeissoschizine. Then, the biosynthesis of most alkaloids containing the unperturbed monoterpenoid part (Corynanthe type) proceeds through cyclization with the formation of cathenamine and subsequent reduction to ajmalicine in the presence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). In the biosynthesis of other alkaloids, 4,21-dehydrogeissoschizine first converts into preakuammicine (an alkaloid of subtype strychnos, type Corynanthe) which gives rise to other alkaloids of subtype strychnos and of the types Iboga and Aspidosperma. Bisindole alkaloids vinblastine and vincristine are produced in the reaction involving catharanthine (alkaloid of type Iboga) and vindolin (type Aspidosperma).[29][44]

Physiological activity

Indole alkaloids act on the central and peripheral nervous systems. Besides, bisindole alkaloids vinblastine and vincristine show antineoplastic effect.[45]

Because of structural similarities with serotonin, many tryptamines can interact with serotonin 5-HT receptors.[46] The main effect of the serotonergic psychedelics such as LSD, DMT, and psilocybin is related to them being agonists of the 5-HT2A receptors.[47][48] In contrast, gramine is an antagonist of the 5-HT2A receptor.[49]

Ergolines, such as lysergic acid, include structural elements of both tryptamine and phenylethylamine and thus act on the whole group of the 5-HT receptors, adrenoceptors (mostly of type α) and dopamine receptors (mostly type D2).[50][51] So ergotamine is a partial agonist of α-adrenergic and 5-HT2 receptors, and thus narrows blood vessels and stimulates constriction of the uterus. Dihydroergotamine is more selective to α-adrenergic receptors and has a weaker effect on serotonin receptors. Ergometrine is an agonist of α-adrenergic, 5-HT2 and partly D2 receptors.[51][52] Compared with other ergot alkaloids, ergometrine has a greater selectivity in stimulating the uterus.[52] LSD, a semi-synthetic psychedelic ergoline, is an agonist of 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A and to a lesser extent D2 receptors and has a powerful psychedelic effect.[53][54]

Some monoterpenoid indole alkaloids also interact with adrenoceptors. For example, ajmalicine is a selective antagonist of α1-adrenergic receptors and therefore has antihypertensive action.[55][56] Yohimbine is more selective to α2 adrenoceptor;[56] by blocking presynaptic α2-adrenoceptors, it increases the release of norepinephrine thereby raising the blood pressure. Yohimbine was used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men until emergence of more efficient drugs.[57]

Some alkaloids affect the turnover of monoamines indirectly. So, harmine and harmaline are reversible selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase-A.[58] Reserpine reduces concentration of monoamines in presynaptic and synaptic neurons, thereby inducing antihypertensive and antipsychotic effects.[55]

Some indole alkaloids interact with other types of receptors. Mitragynine is an agonist of the μ-opioid receptor.[30] Harmal alkaloids are antagonists to the GABAA-receptor,[59] and ibogaine – to NMDA-receptors.[60] Physostigmine is a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.[61]

Applications

Plants and fungi that contain indole alkaloids have a long history of use in traditional medicine. Rauvolfia serpentina, which contains reserpine as the active substance, was used for over 3000 years in India to treat snake bites and insanity.[62] In medieval Europe, extracts of ergot were used in medical abortion.[63]

Later, the plants were joined by pure preparations of indole alkaloids. Reserpine was the second (after chlorpromazine) antipsychotic drug; however, it showed relatively weak action and strong side effects, and is not used for this purpose any longer.[64] Instead, it is prescribed as an antihypertensive drug, often in combination with other substances.[65]

Other drugs that affect the cardiovascular system include ajmaline, which is a Class I antiarrhythmic agents,[66] and ajmalicine, which is used in Europe as an antihypertensive drug.[55] Physostigmine – an inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase – and its synthetic analogs are used in the treatment of glaucoma, Alzheimer's disease (rivastigmine) and myasthenia (neostigmine, pyridostigmine, distigmine).[67] Ergot alkaloids ergometrine (ergobazin, ergonovine), ergotamine and their synthetic derivatives (methylergometrine) are applied against uterine bleeding,[68] and bisindole alkaloids vinblastine and vincristine are antitumor agents.[69]

Animal studies have shown that ibogaine has a potential in treating heroin, cocaine, and alcohol addictions, which is associated with the ibogaine antagonism to NMDA-receptors. Medical use of ibogaine is hindered by its legal status, as it is banned in many countries as a powerful psychedelic drug with dangerous implications of overdose. However, illegal network in Europe and United States provide ibogaine for treating drug addiction.[70][71]

Since ancient times, plants containing indole alkaloids have been used as psychedelic drugs. The Aztecs used and the Mazatec people continue to use psilocybin mushrooms and the psychoactive seeds of morning glory species like Ipomoea tricolor.[72] Amazonian tribes use the psychedelic infusion, ayahuasca, made from Psychotria viridis and Banisteriopsis caapi.[73] Psychotria viridis contains the psychedelic drug DMT, while Banisteriopsis caapi contains harmala alkaloids, which act as monoamine oxidase inhibitors. It is believed that the main function of the harmala alkaloids in ayahuasca is to prevent the metabolization of DMT in the digestive tract and liver, so it can cross the blood–brain barrier, whereas the direct effect of harmala alkaloids on the central nervous system is minimal.[74] The venom of the Colorado River toad, Bufo alvarius, may have used as a psychedelic drug, its active constituents being 5-MeO-DMT and bufotenin.[75] One of the most common recreational psychedelic drugs, LSD, is a semi-synthetic ergoline (which contains the indole moiety).[76]

References

- David S. Seigler (2001). Plant secondary metabolism. Springer. p. 628. ISBN 0-412-01981-7.

- I. L. Knunyants (1988). Chemical Encyclopedia. Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 623.

- Dewick, pp. 348–367.

- Hesse, pp. 333–335.

- Hesse, p. 316.

- Orekhov, p. 616

- L. Elderfild (1954). Heterocyclic compounds. Vol. 3. Moscow. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Dewick, pp. 346–376.

- Hesse, pp. 14–30.

- Hesse, pp. 91–92.

- Hesse, p. 15

- Leland J. Cseke; et al. (2006). Natural Products from Plants. Second Edition. CRC. p. 30. ISBN 0-8493-2976-0.

- Dewick, p. 347

- Dewick, p. 350.

- Hesse, p. 16.

- Glawischnig (2007). "Camalexin". Phytochemistry. 68 (4): 401–406. Bibcode:2007PChem..68..401G. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.12.005. PMID 17217970.

- Dewick, p. 349

- Hesse, p. 22

- Goebel, Fr. (1838). "Ueber das Harmalin". Annalen der Chemie (in German). 38 (3): 363–366. doi:10.1002/jlac.18410380318.

- Orekhov, p. 565.

- Fritzche, J. (1848). "Untersuchungen über die Samen von Peganum Harmala". Journal für Praktische Chemie (in German). 43: 144–155. doi:10.1002/prac.18480430114.

- "Bestandtheile der Samen von Peganum harmala". Annalen der Chemie (in German). 64 (3): 360–369. 1848. doi:10.1002/jlac.18480640353.

- Dewick, pp. 365–366

- Jobst, J.; Hesse, O. (1864). "Ueber die Bohne von Calabar". Annalen der Chemie (in German). 129 (1): 115–121. doi:10.1002/jlac.18641290114.

- Goldfrank, Lewis R. and Flomenbaum, Neal Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2006 ISBN 0-07-147914-7 p. 794.

- Dewick, pp. 370–372.

- Orekhov, p. 627.

- Dewick, p. 351

- Dewick, pp. 350–359

- Hiromitsu Takayama (2004). "Chemistry and Pharmacology of Analgesic Indole Alkaloids from the Rubiaceous Plant, Mitragyna speciosa". Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 52 (8): 916–928. doi:10.1248/cpb.52.916. PMID 15304982.

- Hesse, p. 30

- Hesse, pp. 91–105

- Hesse, p. 99

- Waksmundzka, pp. 625–626

- Tadeusz Aniszewski (2007). Alkaloids – secrets of life. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-444-52736-3.

- Waksmundzka, p. 626

- Tadeusz Aniszewski (2007). Alkaloids – secrets of life. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-444-52736-3.

- Michael E. Peterson; Patricia A. Talcott (2005). Small Animal Toxicology. Saunders. p. 1086. ISBN 0-7216-0639-3.

- Waksmundzka, p. 625

- Kulshreshtha, Ankita; Saxena, Jyoti (2019). "Alkaloids and Non Alkaloids of Tabernaemontana divaricata" (PDF). International Journal of Research and Review. 6 (8): 517–524.

- Fricke, Janis; Blei, Felix; Hoffmeister, Dirk (2017-09-25). "Enzymatic Synthesis of Psilocybin". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 56 (40): 12352–12355. doi:10.1002/anie.201705489. PMID 28763571.

- Dewick, pp. 349, 365

- Dewick, pp. 369–370

- Tadhg P. Begley (2009). Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology. Wiley. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-471-75477-0.

- Dewick, p. 356

- Richard A. Glennon (2006). "Strategies for the Development of Selective Serotonergic Agents". The Serotonin Receptors. From Molecular Pharmacology to Human Therapeutics. Humana Press. p. 96. ISBN 1-58829-568-0.

- Richard A. Glennon (2008). "Neurobiology of Hallucinogens". The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of substance abuse treatment. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- Alper, p. 8

- Froldi Guglielmina; Silvestrin Barbara; Dorigo Paola; Caparrotta Laura (2004). "Gramine: A vasorelaxing alkaloid acting on 5-HT2A receptors". Planta Medica. 70 (4): 373–375. doi:10.1055/s-2004-818953. PMID 15095157. S2CID 30719642.

- Dewick, pp. 374–375

- B. T. Larson; et al. (1995). "Ergovaline Binding and Activation of D2 Dopamine Receptors in GH4ZR7 Cells". Journal of Animal Science. 73 (5): 1396–1400. doi:10.2527/1995.7351396x. PMID 7665369.

- Bertram G. Katzung (2009). Basic and clinical pharmacology. McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-07-160405-5.

- Torsten Passie; et al. (2008). "The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review" (PDF). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. PMC 6494066. PMID 19040555.

- Seeman, P. (2004). "Comment on "Diverse Psychotomimetics Act Through a Common Signaling Pathway"". Science. 305 (5681): 180c. doi:10.1126/science.1096072. PMID 15247457.

- Dewick, p. 353

- Demichel, P; Gomond, P; Roquebert, J (1982). "alpha-Adrenoceptor blocking properties of raubasine in pithed rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 77 (3): 449–454. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1982.tb09317.x. PMC 2044614. PMID 6128043.

- Bertram G. Katzung (2009). Basic & clinical pharmacology. McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-07-160405-5.

- Andreas Moser (1998). Pharmacology of endogenous neurotoxins: a handbook. Braun-Brumfield. p. 138. ISBN 3-7643-3993-4.

- Andreas Moser (1998). Pharmacology of endogenous neurotoxins: a handbook. Braun-Brumfield. p. 131. ISBN 3-7643-3993-4.

- Alper, p. 7

- Dewick, p. 367

- Dewick, p. 352

- Hesse, pp. 332–333

- Alan F. Schatzberg; Charles B. Nemeroff (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. The American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 533. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9.

- Симпатолитики (in Russian).

- Антиаритмические средства (in Russian).

- Dewick, pp. 367–368

- Утеротоники [(Uterotonics)] (in Russian).

- "Противоопухолевые средства растительного происхождения (Antitumor agents in plants)" (in Russian).

- Alper, pp. 2–19

- Dewick, p. 357

- Dewick, p. 348

- Christina Pratt (2007) An Encyclopedia of Shamanism Volume 1, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 1-4042-1140-3 p. 310

- Jordi Riba; et al. (2003). "Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion, and Pharmacokinetics". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 306 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.049882. PMID 12660312. S2CID 6147566.

- A.T. Weil; W. Davis (1994). "Bufo alvarius: a potent hallucinogen of animal origin". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 41 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90051-5. PMID 8170151.

- Dewick, p. 376

Bibliography

- Alper, Kenneth R (2001). "Ibogaine: a Review". The Alkaloids. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-053206-9.

- Dewick, Paul M (2002). Medicinal Natural Products. A Biosynthetic Approach. Second Edition. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-49640-5.

- Hesse, Manfred (2002). Alkaloids. Nature's Curse or Blessing. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-906390-24-6.

- Orekhov AP (1955). Chemistry Alkaloids (2 ed.). M.: USSR.

- Waksmundzka-Hajnos, Monika; Sherma, Joseph; Kowalska, Teresa (2008). Thin layer chromatography in phytochemistry. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-4677-9.