India in World War II

During the Second World War (1939–1945), India was a part of the British Empire. British India officially declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939.[1] India, as a part of the Allied Nations, sent over two and a half million soldiers to fight under British command against the Axis powers. India was also used as the base for American operations in support of China in the China Burma India Theater.

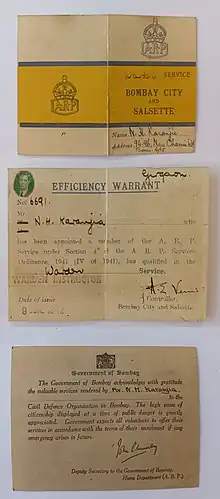

_duties_in_Bombay%252C_1942._IND1492.jpg.webp)

Indians fought with distinction throughout the world, including in the European theatre against Germany, North African Campaign against fascist Italy, and in the southeast Asian theatre; while also defending the Indian subcontinent against the Japanese forces, including British Burma and the Crown colony of Ceylon. Indian troops were also redeployed in former colonies such as Singapore and Hong Kong, with the Japanese surrender in August 1945, after the end of World War II. Over 87,000 Indian troops, and 3 million civilians died in World War II.[2][3] Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, former Commander-in-Chief, India, stated that Britain "couldn't have come through both wars [World War I and II] if they hadn't had the Indian Army."[4][5]

There was pushback throughout India to expending lives supporting the British Empire in Africa and Europe amidst movements for Indian independence. Particularly, Subhas Chandra Bose sought alliance with the Soviet Union and then ultimately with Nazi Germany as a tool for subverting the British empire. Many factions of the Indian Independence Movement did support Nazi Germany during the war, most notably the so-called Indian Legion which Bose was instrumental in creating and which was incorporated for sometime as a division of the Waffen-SS. [6]

Viceroy Linlithgow declared that India was at war with Germany without consultations with Indian politicians.[7] Political parties such as the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha supported the British war effort while the largest and most influential political party existing in India at the time, the Indian National Congress, demanded independence before it would help Britain.[8][9] London refused, and when Congress announced a "Quit India" campaign in August 1942, tens of thousands of its leaders were imprisoned by the British for the duration. Meanwhile, under the leadership of Indian leader Subhash Chandra Bose, Japan set up an army of Indian POWs known as the Indian National Army, which fought against the British. A major famine in Bengal in 1943 led to between 0.8 and 3.8 million deaths due to starvation, and a highly controversial issue remains regarding Churchill's decision to not provide emergency food relief.[10][11]

Indian participation in the Allied campaign remained strong. The financial, industrial and military assistance of India formed a crucial component of the British campaign against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.[12] India's strategic location at the tip of the Indian Ocean, its large production of armaments, and its huge armed forces played a decisive role in halting the progress of Imperial Japan in the South-East Asian theatre.[13] The Indian Army during World War II was one of the largest Allied forces contingents which took part in the North and East African Campaign, Western Desert Campaign. At the height of the second World War, more than 2.5 million Indian troops were fighting Axis forces around the globe.[14] After the end of the war, India emerged as the world's fourth largest industrial power and its increased political, economic and military influence paved the way for its independence from the United Kingdom in 1947.[15]

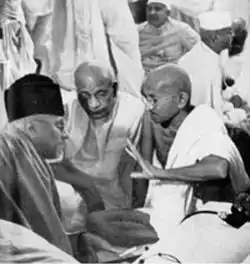

Quit India movement

The Indian National Congress, led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Maulana Azad, denounced Nazi Germany but would not fight it or anyone else until India was independent.[16] Congress launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942, refusing to co-operate in any way with the government until independence was granted. The government, not ready for this, immediately arrested over 60,000 national and local Congress leaders, and then moved to suppress the violent reaction of Congress supporters. Key leaders were kept in prison until June 1945, although Gandhi was released in May 1944 because of his health. Congress, with its leaders incommunicado, played little role on the home front. Unlike the predominately Hindu Congress, the Muslim League rejected the Quit India movement and worked closely with the Raj authorities.[17]

Supporters of the British Raj argued that decolonisation was impossible in the middle of a great war. So, in 1939, the British Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow declared India's entry into the War without consulting prominent Indian Congress leaders who were just elected in previous elections.[1]

Subhas Chandra Bose (also called Netaji) had been a top Congress leader. He broke up with the Congress and tried to form a military alliance with Germany or Japan to gain independence. Bose, with the assistance of Germany, formed the Indian Legion from Indian students in Axis occupied Europe and Indian Army prisoners of war. With German reversals in 1942 and 1943, Bose and the Legion's officers were transported by U boat to Japanese territory to continue his plans. Upon arrival, Japan helped him set up the Indian National Army (INA) which fought under Japanese direction, mostly in the Burma Campaign. Bose also headed the Provisional Government of Free India, a government-in-exile based in Singapore. It controlled no Indian territory and was used only to raise troops for Japan.[18]

British Indian Army

.jpg.webp)

In 1939 the British Indian Army numbered 205,000 men. It took in volunteers and by 1945 was the largest all-volunteer force in history, rising to over 3.35 million men.[19] These forces included tank, artillery and airborne forces. Indian personnel of the British Indian Army received 6,000 awards for gallantry, including 31 Victoria Crosses.[20]

The Middle East and African theatre

The British government meanwhile sent Indian troops to fight in West Asia and northern Africa against the Axis. India also geared up to produce essential goods such as food and uniforms.

The 4th, 5th and 10th Indian Divisions took part in the North African theatre against Rommel's Afrika Korps. In addition, the 18th Brigade of the 8th Indian Division fought at Alamein. Earlier, the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions took part in the East African campaign against the Italians in Somaliland, Eritrea and Abyssinia capturing the mountain fortress of Keren.

In the Battle of Bir Hacheim, Indian gunners played an important role by using guns in the anti tank role and destroying tanks of Rommel's panzer divisions. Maj PPK Kumaramangalam was the battery commander of 41 Field Regiment which was deployed in the anti tank role. He was awarded the DSO for his act of bravery. Later he became the Chief of Army Staff of India in 1967.

South-East Asian theatre

The British Indian Army was the key British Empire fighting presence in the Burma Campaign. The Royal Indian Air force's first assault mission was carried out against Japanese troops stationed in Burma. The British Indian Army was key to breaking the siege of Imphal when the westward advance of Imperial Japan came to a halt.

The formations included the Indian III Corps, IV Corps, the Indian XXXIII Corps and the Fourteenth Army. As part of the new concept of Long Range Penetration (LRP), Gurkha troops of the Indian Army were trained in the present state of Madhya Pradesh under their commander (later Major General) Orde Charles Wingate.

These troops, popularly known as Chindits, played a crucial role in halting the Japanese advance into South Asia.[21]

Capture of Indian territory

By 1942, neighbouring Burma was invaded by Japan, which by then had already captured the Indian territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Japan gave nominal control of the islands to the Provisional Government of Free India on 21 October 1943, and in the following March, the Indian National Army with the help of Japan crossed into India and advanced as far as Kohima in Nagaland. This advance on the mainland of South Asia reached its farthest point on India territory, with the Japanese finally retreating from the Battle of Kohima and near simultaneous Battle of Imphal in June 1944.[22]

Recapture of Axis-occupied territory

In 1944–45 Japan was under heavy air bombardment at home and suffered massive naval defeats in the Pacific. As its Imphal offensive failed, harsh weather and disease and withdrawal of air cover (due to more pressing needs in the Pacific) also took its toll on the Japanese and remnants of the INA and the Burma National Army. In spring 1945, a resurgent British army recaptured the occupied lands.[23]

The invasion of Italy

Indian forces played a role in liberating Italy from Nazi control. India contributed the third largest Allied contingent in the Italian campaign after US and British forces. The 4th, 8th and 10th Divisions and 43rd Gurkha Infantry Brigade led the advance, notably at the gruelling Battle of Monte Cassino. They fought on the Gothic Line in 1944 and 1945.

Royal Indian Air Force

During World War II, the IAF played an instrumental role in halting the advance of the Japanese army in Burma, where the first IAF air strike was executed. The target for this first mission was the Japanese military base in Arakan, after which IAF strike missions continued against the Japanese airbases at Mae Hong Son, Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai in northern Thailand.

The IAF was mainly involved in strike, close air support, aerial reconnaissance, bomber escort and pathfinding missions for RAF and USAAF heavy bombers. RAF and IAF pilots would train by flying with their non-native air wings to gain combat experience and communication proficiency. Besides operations in the Burma Theatre IAF pilots participated in air operations in North Africa and Europe.[24]

In addition to the IAF, many native Indians and some 200 Indians resident in Britain volunteered to join the RAF and Women's Auxiliary Air Force. One such volunteer was Sergeant Shailendra Eknath Sukthankar, who served as a navigator with No. 83 Squadron. Sukthankar was commissioned as an officer, and on 14 September 1943, received the DFC. Squadron Leader Sukthankar eventually completed 45 operations, 14 of them on board the RAF Museum's Avro Lancaster R5868. Another volunteer was Assistant Section Officer Noor Inayat Khan a Muslim pacifist and Indian nationalist who joined the WAAF, in November 1940, to fight against Nazism. Noor Khan served bravely as a secret agent with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in France, but was eventually betrayed and captured.[24] Many of these Indian airmen were seconded or transferred to the expanding IAF such as Squadron Leader Mohinder Singh Pujji DFC who led No. 4 Squadron IAF in Burma.

During the war, the IAF experienced a phase of steady expansion. New aircraft added to the fleet included the US-built Vultee Vengeance, Douglas Dakota, the British Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire, Bristol Blenheim, and Westland Lysander.

Subhas Chandra Bose sent Indian National Army youth cadets to Japan to train as pilots. They went on to attend the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force Academy in 1944.[25]

In recognition of the valiant service by the IAF, King George VI conferred the prefix "Royal" in 1945. Thereafter the IAF was referred to as the Royal Indian Air Force. In 1950, when India became a republic, the prefix was dropped and it reverted to being the Indian Air Force.[26]

Post war, No. 4 Squadron IAF was sent to Japan as part of the Allied Occupation forces.[27]

Royal Indian Navy

.jpg.webp)

In 1934, the Royal Indian Marine changed its name, with the enactment of the Indian Navy (Discipline) Act of 1934. The Royal Indian Navy was formally inaugurated on 2 October 1934, at Bombay.[28] Its ships carried the prefix HMIS, for His Majesty's Indian Ship.[29]

At the start of the Second World War, the Royal Indian Navy was small, with only eight warships. The onset of the war led to an expansion in vessels and personnel described by one writer as "phenomenal". By 1943 the strength of the RIN had reached twenty thousand.[30] During the War, the Women's Royal Indian Naval Service was established, for the first time giving women a role in the navy, although they did not serve on board its ships.[28]

During the course of the war six anti-aircraft sloops and several fleet minesweepers were built in the United Kingdom for the R.I.N. After commissioning, many of these ships joined various escort groups operating in the northern approaches to the British Isles. HMIS Sutlej and HMIS Jumna, each armed with six-high angle 4" guns, were present during the Clyde "Blitz" of 1941 and assisted the defence of this area by providing anti-aircraft cover. For the next six months these two ships joined the Clyde Escort Force, operating in the Atlantic and later the Irish Sea Escort Force where they acted as the senior ships of the groups. While engaged on these duties, numerous attacks against U-boats were carried out and attacks by hostile aircraft repelled. At the time of action in which the Bismarck was involved, the Sutlej left Scapa Flow, with all despatch as the senior member of a group, to take over a convoy from the destroyers which were finally engaged in the sinking of the Bismarck.[31]

Later HMIS Cauvery, HMIS Kistna, HMIS Narbada, HMIS Godavari, also antiaircraft sloops, completed similar periods in the U.K. waters escorting convoys in the Atlantic and dealing with attacks from hostile U-boats, aircraft and glider bombs. These six ships and the minesweepers all eventually proceeded to India carrying out various duties in the North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Cape stations en route. The fleet minesweepers were HMIS Kathiawar, HMIS Kumaon, HMIS Baluchistan, HMIS Carnatic, HMIS Khyber, HMIS Konkan, HMIS Orissa, HMIS Rajputana, HMIS Rohilkhand.[31]

HMIS Bengal was a part of the Eastern Fleet during World War II, and escorted numerous convoys between 1942 and 1945.[32]

The sloops HMIS Sutlej and HMIS Jumna played a role in Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily by providing air defence and anti-submarine screening to the invasion fleet.[33][34]

Furthermore, the Royal Indian Navy participated in convoy escort duties in the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean and was heavily involved in combat operations as part of the Burma Campaign, carrying out raids, shore bombardment, naval invasion support and other activities culminating in Operation Dracula and the mopping up operations during the final stages of the war.[35]

Royal Indian Naval combat losses

The sloop HMIS Pathan sunk in June 1940 by the Italian Navy Submarine Galvani during the East African Campaign[36][37][38][39]

In the days immediately following the Attack on Pearl Harbor, HMS Glasgow was patrolling the Laccadive Islands in search of Japanese ships and submarines. At midnight on 9 December 1941, HMS Glasgow sank the RIN patrol vessel HMIS Prabhavati with two lighters in tow en route to Karachi, with 6-inch shells at 6,000 yards (5,500 m). Prabhavati was alongside the lighters and was mistaken for a surfaced Japanese submarine.[40][41][42]

HMIS Indus was sunk by Japanese aircraft during Burma Campaign on 6 April 1942.[43]

Royal Indian Naval successes

HMIS Jumna was ordered in 1939, and built by William Denny and Brothers. She was commissioned in 1941,[44] and with World War II underway, was immediately deployed as a convoy escort. Jumna served as an anti-aircraft escort during the Java Sea campaign in early 1942, and was involved in intensive anti-aircraft action against attacking Japanese twin-engined level bombers and dive bombers, claiming five aircraft downed from 24 to 28 February 1942.

In June 1942 HMIS Bombay was involved in the defence of Sydney Harbour during the attack on Sydney Harbour.

On 11 November 1942, Bengal was escorting the Dutch tanker Ondina[45] to the southwest of Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean. Two Japanese commerce raiders armed with six-inch guns attacked Ondina. Bengal fired her single four-inch gun and Ondina fired her 102 mm and both scored hits on Hōkoku Maru, which shortly blew up and sank.[45][46]

On 12 Feb 1944, the Japanese submarine RO-110 was depth charged and sunk east-south-east off Visakhapatnam, India by the Indian sloop HMIS Jumna and the Australian minesweepers HMAS Launceston and HMAS Ipswich (J186). RO-110 had attacked convoy JC-36 (Colombo-Calcutta) and torpedoed and damaged the British merchant Asphalion (6274 GRT).[44][47]

On 12 August 1944 the German submarine U-198 was sunk near the Seychelles, in position 03º35'S, 52º49'E, by depth charges from HMIS Godavari and the British frigate HMS Findhorn.[48][43]

Collaboration with the Axis powers

Several leaders of the radical revolutionary Indian independence movement broke away from the main Congress and went to war against Britain. Subhas Chandra Bose, once a prominent leader in the Indian National Congress, volunteered to help Nazi Germany and Japan; he claimed in speeches that Britain's opposition to Nazism and Fascism was "hypocrisy", since Britain was itself denying individual liberties to Indians.[49] Moreover, he argued that it was not Germany and Japan but the British Raj which was the enemy, since the British were over-exploiting Indian resources for the war.[49] Bose suggested that there was little possibility of India being attacked by any of the Axis powers provided it did not fight the war on Britain's side.[49]

Nazi Germany was encouraging but gave little help. Bose then approached the Japanese Empire at Tokyo, which gave him control of Indian forces it had organised.[51]

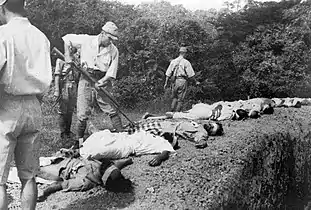

The Indian National Army (INA), formed first by Mohan Singh Deb, consisted initially of prisoners taken by the Japanese in Malaya and at Singapore who were offered the choice of serving the INA by Japan or remaining in very poor conditions in POW camps. Later, after it was reorganised under Subhas Chandra Bose, it drew civilian volunteers from Malaya and Burma. Ultimately, a force of under 40,000 was formed, although only two divisions ever participated in battle. Intelligence and special services groups from the INA were instrumental in destabilising the British Indian Army in the early stages of the Arakan offensive. It was during this time that the British Military Intelligence began propaganda work to shield the true numbers who joined the INA, and also described stories of Japanese brutalities that indicated INA involvement. Further, the Indian press was prohibited from publishing any accounts whatsoever of the INA.

As the Japanese offensive opened, the INA was sent into battle. Bose hoped to avoid set-piece battles for which it lacked arms, armament as well as man-power.[52] Initially, he sought to obtain arms as well as increase its ranks from British Indian soldiers he hoped would defect to his cause. Once the Japanese forces were able to break the British defences at Imphal, he planned for the INA to cross the hills of North-East India into the Gangetic plain, where it was to work as a guerrilla army and expected to live off the land, garner support, supplies, and ranks from amongst the local populace to ultimately touch off a revolution.

Prem Kumar Sahgal, an officer of the INA once Military secretary to Subhas Bose and later tried in the first Red Fort trials, explained that although the war itself hung in balance and nobody was sure if the Japanese would win, initiating a popular revolution with grass-root support within India would ensure that even if Japan lost the war ultimately, Britain would not be in a position to re-assert its colonial authority, which was ultimately the aim of the INA and Azad Hind.

As Japan opened its offensive towards India, the INA's first division, consisting of four Guerrilla regiments, participated in Arakan offensive in 1944, with one battalion reaching as far as Mowdok in Chittagong. Other units were directed to Imphal and Kohima, as well as to protect Japanese flanks to the south of Arakan, a task it successfully carried out. However, the first division suffered the same fate as did Mutaguchi's Army when the siege of Imphal was broken. With little or no supplies and supply lines deluged by the Monsoon, harassed by Allied air dominance, the INA began withdrawing when the 15th Army and Burma Area Army began withdrawing, and suffered the same terrible fate as wounded, starved and diseased men succumbed during the hasty withdrawal into Burma. Later in the war however, the INA's second division, tasked with the defence of Irrawaddy and the adjoining areas around Nangyu, was instrumental in opposing Messervy's 7th Indian Infantry Division when it attempted to cross the river at Pagan and Nyangyu during the successful Burma Campaign by the Allies the following year. The 2nd division was instrumental in denying the 17th Indian Infantry Division the area around Mount Popa that would have exposed the flank of Kimura's forces attempting to retake Meiktila and Nyangyu. Ultimately however, the division was obliterated. Some of the surviving units of the INA surrendered as Rangoon fell, and helped keep order till the allied forces entered the city. The other remnants began a long march over land and on foot towards Singapore, along with Subhas Chandra Bose. As the Japanese situation became precarious, Bose left for Manchuria to attempt to contact the Russians, and was reported to have died in an air crash near Taiwan.

The only Indian territory that the Azad Hind government controlled was nominally the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. However, they were bases for the Japanese Navy, and the navy never relinquished control. Enraged with the lack of administrative control, the Azad Hind Governor, Lt. Col. Loganathan, later relinquished his authority. After the War, a number of officers of the INA were tried for treason. However, faced with the possibility of a massive civil unrest and a mutiny in the Indian Army, the British officials decided to release the prisoners-of-war; in addition, the event became a turning point to expedite the process of transformation of power and independence of India.[53]

Bengal famine

The region of Bengal in India suffered a devastating famine from 1940 to 1943. Some of the key reasons for this famine are:

- British export of food and material for the war in Europe;

- Japanese invasion of Burma which cut off food and other essential supplies to the region;

- British denial orders destroying essential food transportation throughout the Eastern region;

- British banned transfer of grain from other provinces, turning down offers of grain from Australia;

- mismanagement by British Indian regional governments;

- constructing 900 airfields (2000 acres each) taking that huge amount of land out of agriculture in a time of dire need;

- price inflation caused by war production

- increase in demand partially as a result of refugees from Burma and Bengal.

The British government denied an urgent request from Leopold Amery, the Indian secretary of state, and Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy of India, to stop exports of food from Bengal in order that it might be used for famine relief. Winston Churchill, then prime minister, dismissed these requests in a fashion that Amery regarded as "Hitler-like," by asking why, if the famine was so horrible, Gandhi had not yet died of starvation.[54]

Indian Economist Amartya Sen (1976) challenged this orthodoxy, reviving the claim that there was no shortage of food in Bengal and that the famine was caused by inflation.[55]

Princely states

During World War II, in 1941, the British presented a captured German BF 109 single-engined fighter to the Nizam of Hyderabad, in return for the funding of 2 RAF fighter squadrons.[56]

There was a campsite for Polish refugees at Valivade, in Kolhapur State, it was the largest settlement of Polish refugees in India during the war.[57][58][59] Another such campsite for Polish refugee children was located in Balachadi, it was built by K. S. Digvijaysinhji, Jam Saheb Maharaja of Nawanagar State in 1942, near his summer resort. He gave refuge to hundreds of Polish children rescued from Soviet camps (Gulags).[57][60][61] The campsite is now part of the Sainik School.[62]

1944–45 Insurgency in Balochistan

From 1944 to 1945, Daru Khan Badinzai led an insurgency against the authorities of the Raj. It began in the first half of 1944, when rebels of the Badinzai tribe began interfering with road construction on the British side of the Balochistan border.[63] The insurgency had subsided by March 1945.[64]

Mazrak Zadran's invasion of India

In 1944, the Southern and Eastern provinces of Afghanistan entered a state of turmoil, with the Zadran, Safi and Mangal tribes rising up against the Afghan government.[65] Among the leaders of the revolt was the Zadran chieftain, Mazrak Zadran,[66] who opted to invade British-occupied India in late 1944. There he was joined by a Baloch chieftain, Sultan Ahmed.[67] Mazrak was forced to retreat back into Afghanistan due to British aerial bombardment.[68]

See also

Notes

- Kux, Dennis (1992). India and the United States: estranged democracies, 1941–1991. DIANE Publishing, 1992. ISBN 978-1-4289-8189-8.

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission Annual Report 2013-2014 Archived 4 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, page 44. Figures include identified burials and those commemorated by name on memorials.

- Gupta, Diya (8 November 2019). "Hunger, starvation and Indian soldiers in World War II". Livemint. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "The Indian Army in the Second World War". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016.

- "Armed and ready". Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Douds, G.J. (2004). "The men who never were: Indian POWs in the Second World War". South Asia. 27 (2): 183–216. doi:10.1080/1479027042000236634. S2CID 144665659.

- Mishra, Basanta Kumar (1979). "India's Response To The British Offer Of August 1940". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 40: 717–719. JSTOR 44142017.

- Broad, Roger (27 May 2017). Volunteers and Pressed Men: How Britain and its Empire Raised its Forces in Two World Wars. United Kingdom: Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-396-1. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Manu, Bhagavan (2 March 2012). The Peacemakers: India And The Quest For One World. India: HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 978-93-5029-469-7. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- "Has India's contribution to WW2 been ignored?". BBC News. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Mishra, Vimal; Tiwari, Amar Deep; Aadhar, Saran; Shah, Reepal; Xiao, Mu; Pai, D. S.; Lettenmaier, Dennis (28 February 2019). "Drought and Famine in India, 1870–2016". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (4): 2075–2083. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..46.2075M. doi:10.1029/2018GL081477. S2CID 133752333. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Weigold, Auriol (6 June 2008). Churchill, Roosevelt and India: Propaganda During World War II. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-89450-7. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2015 – via Google Books.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (21 April 2019). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: F-L. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30742-3. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2015 – via Google Books.

- Leonard, Thomas M. (21 April 2019). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2015 – via Google Books.

- Cohen, Stephen P. (13 May 2004). India: Emerging Power - By Stephen P. Cohen. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8157-9839-3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Frank Moraes (2007). Jawaharlal Nehru. Jaico Publishing House. p. 266. ISBN 978-81-7992-695-6. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Sankar Ghose (1993). Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography. Allied Publishers. pp. 114–18. ISBN 978-81-7023-343-5. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Leonard A. Gordon, Brothers Against the Raj: A Biography of Indian Nationalists Sarat & Subhas Chandra Bose (2000)

- Compton McKenzie (1951). Eastern Epic. Chatto & Windus, London., p. 1

- Sherwood, Marika. "Colonies, Colonials and World War Two". BBC History. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- Peter Liddle; J. M. Bourne; Ian R. Whitehead (2000). The Great World War, 1914–45: Lightning strikes twice. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-472454-6.

- Allen, Louis (1998). Burma: The Longest War. Phoenix Giant. p. 638. ISBN 978-0753802212.

- Edward M. Young and Howard Gerrard, Meiktila 1945: The Battle To Liberate Burma (2004)

- "Royal Indian Air Force". RAF Museum. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Burma to Japan with Azad Hind: A War Memoir (1941–1945) Archived 13 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine Air Cmde R S Benegal MVC AVSM

- Ahluwalia, A. (2012). Airborne to Chairborne: Memoirs of a War Veteran Aviator-Lawyer of the Indian Air Force. Xlibris Corporation. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4691-9657-2. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- http://indianairforce.nic.in/show_unit.php?ch=7 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Bhatia (1977), p. 28

- D. J. E. Collins, The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–45, vol. 1 (Bombay, 1964)

- Mollo, Andrew (1976). Naval, Marine and Air Force uniforms of World War 2. p. 144. ISBN 0-02-579391-8.

- The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945 – Collins, p. 248

- Kindell, Don. "Eastern Fleet – January to June 1943". Admiralty War Diaries of World War 2. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- Inmed Archived 24 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945 –Collins, p. 252

- The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945 – Collins, pp. 255–316

- Rohwer & Hummelchen, p. 23

- Collins, D.J.E. (1964). "Combined Inter-Services Historical Section (India & Pakistan)". The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945, Official History of the Indian Armed Forces In the Second World War. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "House of commons debate - Indian, Burman, and Colonial War Effort". House of Commons of the United Kingdom. 20 November 1940. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Fighting the U-boats = Indian Naval forces". Uboat.net. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Allied Warships – HMIS Prabhavati". Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945 – Collins, p. 96

- Neil MacCart, Town Class Cruisers, Maritime Books, 2012, ISBN 978-1-904-45952-1, p. 153

- Collins, J.T.E. (1964). The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945. Official History of the Indian Armed Forces In the Second World War. New Delhi: Combined Inter-Services Historical Section (India and Pakistan). Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "HMIS Jumna (U 21)". uboat.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Visser, Jan (1999–2000). "The Ondina Story". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- L, Klemen (2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- The Royal Indian Navy, 1939–1945 – Collins, p. 309

- "HMIS Godavari (U 52) of the Royal Indian Navy – Indian Sloop of the Black Swan class – Allied Warships of WWII – uboat.net". Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- Bose, Subash Chandra (2004). Azad Hind: writings and speeches, 1941–43. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-083-9.

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2000), Intelligence and the War Against Japan: Britain, America and the Politics of Secret Service, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 371, ISBN 978-0-521-64186-9, archived from the original on 22 October 2020, retrieved 6 November 2013

- Horn, Steve (2005). The second attack on Pearl Harbor: Operation K and other Japanese attempts to bomb America in World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-388-8.

- Fay 1993, pp. 292, 298

- Fay 1993

- Mishra, Pankaj (6 August 2007). "Exit Wounds". Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2019 – via www.newyorker.com.

- Khan, Yasmin (2008). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3.

- Manu Pubby (4 November 2006). "A mystery behind the history plane". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (2015). The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersal Throughout the World. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5536-2. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- Phadnis, Samrat (13 February 2014). "Over 70 Polish refugees to visit city in March, relive WW-II memories". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020.

- Deshpande, Devidas (31 July 2011). "The last Pole of Valivade". Pune Mirror. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019.

- "Little Warsaw Of Kathiawar". Outlook. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Good Maharaja saves Polish children – beautiful story of A Little Poland in India". newdelhi.mfa.gov.pl. 10 November 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Origin and History". Welcome to Sainik School Balachadi. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Preston, Paul; Partridge, Michael; Yapp, Malcolm (1997). British Documents on Foreign Affairs – reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Eastern Affairs, January 1944 – June 1944. University Publications of America. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-55655-671-5. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Preston, Paul; Partridge, Michael; Yapp, Malcolm (1997). British Documents on Foreign Affairs – reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Eastern affairs, July 1944 – March 1945. University Publications of America. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-55655-671-5. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Giustozzi, Antonio (November 2008). "Afghanistan: transition without end" (PDF). Crisis States Working Papers. p. 13. S2CID 54592886.

- "Coll 5/73 'Afghan Air Force: Reports on' [57r] (113/431)". Qatar Digital Library. 21 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Yapp, Malcolm (2001). British documents on foreign affairs: reports and papers from the foreign office confidential print. From 1946 through 1950. Near and Middle-East 1947. Afghanistan, Persia and Turkey, January 1947 – December 1947. University Publications of America. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-55655-765-1. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Preston, Paul; Partridge, Michael; Yapp, Malcolm (1997). British Documents on Foreign Affairs – reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Eastern affairs, July 1944 – March 1945. University Publications of America. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-55655-671-5. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Further reading

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India (2004)

- Barkawi, Tarak. "Culture and Combat In the Colonies: The Indian Army In the Second World War," Journal of Contemporary History (2006) 41#2 pp 325–355 doi:10.1177/0022009406062071 online

- Bhatia, Harbans Singh, Military History of British India, 1607–1947 (1977)

- Brown, Judith M. Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy (1994)

- Brown, Judith M. Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope (1991)

- Fay, Peter W. (1993), The Forgotten Army: India's Armed Struggle for Independence, 1942–1945., Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press., ISBN 0-472-08342-2.

- Collins, D.J.E. The Royal Indian Navy (1964 online official history

- Gopal, Sarvepalli. Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography (1976)

- Herman, Arthur. Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age (2009), pp 443–539.

- Hogan, David W. India-Burma. World War II Campaign Brochures. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-5. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Jalal, Ayesha. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (1993),

- James, Lawrence. Raj: the making and remaking of British India (1997) pp 545–85, narrative history.

- Joshi, Vandana. "Memory and Memorialisation, Interment and Exhumation, Propaganda and Politics during WWII through the lens of International Tracing Service (ITS) Collections", in MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019), pp. 1–12.

- Judd, Dennis. The Lion and the Tiger: The Rise and Fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947 (2004)

- Karnad, Raghu. Farthest Field – An Indian Story of the Second World War (Harper Collins India, 2015) ISBN 93-5177-203-9

- Khan, Yasmin. India At War: The Subcontinent and the Second World War (2015), wide-ranging scholarly survey excerpt; also published as The Raj At War: A People's History Of India's Second World War (2015)' online review

- Marston, Daniel. The Indian Army and the end of the Raj (Cambridge UP, 2014).

- Moore, Robin J. "India in the 1940s", in Robin Winks, ed. Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography (2001), pp. 231–242

- Mukerjee, Madhusree. Churchill's Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II (2010).

- Raghavan, Srinath. India's War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia (2016). wide-ranging scholarly survey excerpt

- Read, Anthony, and David Fisher. The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence (1999) detailed scholarly history of 1940–47

- Roy, Kaushik. "Military Loyalty in the Colonial Context: A Case Study of the Indian Army during World War II." Journal of Military History 73.2 (2009): 497–529.

- Voigt, Johannes. India in The Second World War (1988).

- Wolpert, Stanley A. Jinnah of Pakistan (2005).

External links

Media related to India in World War II at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to India in World War II at Wikimedia Commons