Imperial Airways

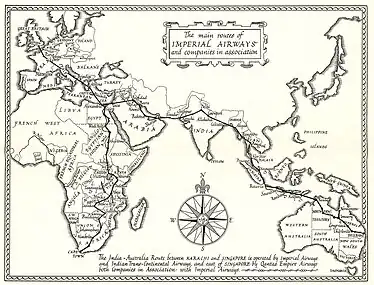

Imperial Airways was an early British commercial long-range airline, operating from 1924 to 1939 and principally serving the British Empire routes to South Africa, India, Australia and the Far East, including Malaya and Hong Kong. Passengers were typically businessmen or colonial administrators, and most flights carried about 20 passengers or fewer. Accidents were frequent: in the first six years, 32 people died in seven incidents. Imperial Airways never achieved the levels of technological innovation of its competitors and was merged into the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) in 1939. BOAC in turn merged with the British European Airways (BEA) in 1974 to form British Airways.

Imperial Airways Speedbird logo, mainly used in advertising and rarely on aircraft before 1939 | |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Air transport |

| Predecessor | |

| Founded | 31 March 1924 |

| Defunct | 24 November 1939 |

| Fate | Merged with British Airways Ltd |

| Successor | British Overseas Airways Corporation |

| Headquarters | , England |

Background

The establishment of Imperial Airways occurred in the context of facilitating overseas settlement by making travel to and from the colonies quicker, and that flight would also speed up colonial government and trade that was until then dependent upon ships. The launch of the airline followed a burst of air route surveying in the British Empire after the First World War, and after some experimental (and often dangerous) long-distance flying to the margins of Empire.[1]

Formation

Imperial Airways was created against a background of stiff competition from French and German airlines that enjoyed heavy government subsidies and following the advice of the government's Hambling Committee (formally known as the C.A.T Subsidies Committee) under Sir Herbert Hambling.[2] The committee, set up on 2 January 1923, produced a report on 15 February 1923 recommending that four of the largest existing airlines, the Instone Air Line Company, owned by shipping magnate Samuel Instone, Noel Pemberton Billing's British Marine Air Navigation (part of the Supermarine flying-boat company), the Daimler Airway, under the management of George Edward Woods, and Handley Page Transport Co Ltd., should be merged.[3][4] It was hoped that this would create a company which could compete against French and German competition and would be strong enough to develop Britain's external air services while minimizing government subsidies for duplicated services. With this in view, a £1m subsidy over ten years was offered to encourage the merger. Agreement was made between the President of the Air Council and the British, Foreign and Colonial Corporation on 3 December 1923 for the company, under the title of the 'Imperial Air Transport Company' to acquire existing air transport services in the UK. The agreement set out the government subsidies for the new company: £137,000 in the first year diminishing to £32,000 in the tenth year as well as minimum mileages to be achieved and penalties if these weren't met.[5]

Imperial Airways Limited was formed on 31 March 1924 with equipment from each contributing concern: British Marine Air Navigation Company Ltd, the Daimler Airway, Handley Page Transport Ltd and the Instone Air Line Ltd. Sir Eric Geddes was appointed the chairman of the board with one director from each of the merged companies. The government had appointed two directors, Hambling (who was also President of the Institute of Bankers) and Major John Hills, a former Treasury Financial Secretary.[4]

The land operations were based at Croydon Airport to the south of London. IAL immediately discontinued its predecessors' service to points north of London, the airline being focused on international and imperial service rather than domestic. Thereafter the only IAL aircraft operating 'North of Watford' were charter flights.

Industrial troubles with the pilots delayed the start of services until 26 April 1924, when a daily London–Paris route was opened with a de Havilland DH.34.[6] Thereafter the task of expanding the routes between England and the Continent began, with Southampton–Guernsey on 1 May 1924, London-Brussels–Cologne on 3 May, London–Amsterdam on 2 June 1924, and a summer service from London–Paris–Basel–Zürich on 17 June 1924. The first new airliner ordered by Imperial Airways, was the Handley Page W8f City of Washington, delivered on 3 November 1924.[7] In the first year of operation the company carried 11,395 passengers and 212,380 letters. In April 1925, the film The Lost World became the first film to be screened for passengers on a scheduled airliner flight when it was shown on the London-Paris route.[8]

Empire services

Air routes between England, India, Australia and South Africa

Route proving

Between 16 November 1925 and 13 March 1926, Alan Cobham made an Imperial Airways' route survey flight from the UK to Cape Town and back in the Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar–powered de Havilland DH.50J floatplane G-EBFO. The outward route was London–Paris–Marseille–Pisa–Taranto–Athens–Sollum–Cairo–Luxor–Aswan–Wadi Halfa–Atbara–Khartoum–Malakal–Mongalla–Jinja–Kisumu–Tabora–Abercorn–Ndola–Broken Hill–Livingstone–Bulawayo–Pretoria–Johannesburg–Kimberley–Bloemfontein–Cape Town. On his return Cobham was awarded the Air Force Cross for his services to aviation.[9]

On 30 June 1926, Cobham took off from the River Medway at Rochester in G-EBFO to make an Imperial Airways route survey for a service to Melbourne, arriving on 15 August 1926. He left Melbourne on 29 August 1926, and, after completing 28,000 nautical miles (32,000 mi; 52,000 km) in 320 hours flying time over 78 days, he alighted on the Thames at Westminster on 1 October 1926. Cobham was met by the Secretary of State for Air, Sir Samuel Hoare, and was subsequently knighted by HM King George V.[10]

On 27 December 1926, Imperial Airways de Havilland DH.66 Hercules G-EBMX City of Delhi left Croydon for a survey flight to India. The flight reached Karachi on 6 January 1927 and Delhi on 8 January 1927. The aircraft was named by Lady Irwin, wife of the Viceroy, on 10 January 1927. The return flight left on 1 February 1927 and arrived at Heliopolis, Cairo on 7 February 1927. The flying time from Croydon to Delhi was 62 hours 27 minutes and Delhi to Heliopolis 32 hours 50 minutes.[11]

The Eastern Route

Regular services on the Cairo to Basra route began on 12 January 1927 using DH.66 aircraft, replacing the previous RAF mail flight.[11] Following two years of negotiations with the Persian authorities regarding overflight rights, a London to Karachi service started on 30 March 1929, taking seven days and consisting of a flight from London to Basle, a train to Genoa and a Short S.8 Calcutta flying boats to Alexandria, a train to Cairo and finally a DH.66 flight to Karachi. The route was extended as far as Delhi on 29 December 1929. The route across Europe and the Mediterranean changed many times over the next few years but almost always involved a rail journey.

In April 1931 an experimental London-Australia air mail flight took place; the mail was transferred at the Dutch East Indies, after the DH66 City of Cairo crashed landed in Timor, on the 19th April, having run out of fuel, and took 26 days in total to reach Sydney. For the passenger flight leaving London on 1 October 1932, the Eastern route was switched from the Persian to the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf, and Handley Page HP 42 airliners were introduced on the Cairo to Karachi sector. The move saw the establishment of an airport and rest house, Mahatta Fort, in the Trucial State of Sharjah now part of the United Arab Emirates.

On 29 May 1933 an England to Australia survey flight took off, operated by Imperial Airways Armstrong Whitworth Atalanta G-ABTL Astraea. Major H. G. Brackley, Imperial Airways' Air Superintendent, was in charge of the flight. Astraea flew Croydon-Paris-Lyon-Rome-Brindisi-Athens-Alexandria-Cairo where it followed the normal route to Karachi then onwards to Jodhpur-Delhi-Calcutta-Akyab-Rangoon-Bangkok-Prachuab-Alor Setar-Singapore-Palembang-Batavia-Sourabaya-Bima-Koepang-Bathurst Island-Darwin-Newcastle Waters-Camooweal-Cloncurry-Longreach-Roma-Toowoomba reaching Eagle Farm, Brisbane on 23 June. Sydney was visited on 26 June, Canberra on 28 June and Melbourne on 29 June.

There followed a rapid eastern extension. The first London to Calcutta service departed on 1 July 1933, the first London to Rangoon service on 23 September 1933, the first London to Singapore service on 9 December 1933, and the first London to Brisbane service on 8 December 1934, with Qantas responsible for the Singapore to Brisbane sector. (The 1934 start was for mail; passenger flights to Brisbane began the following April.) The first London to Hong Kong passengers departed London on 14 March 1936 following the establishment of a branch from Penang to Hong Kong.

The Africa Route

On 28 February 1931 a weekly service began between London and Mwanza on Lake Victoria in Tanganyika as part of the proposed route to Cape Town. On 9 December 1931 the Imperial Airways' service for Central Africa was extended experimentally to Cape Town for the carriage of Christmas mail. The aircraft used on the last sector, DH66 G-AARY City of Karachi arrived in Cape Town on 21 December 1931. On 20 January 1932 a mail-only route to London to Cape Town was opened. On 27 April this route was opened to passengers and took 10 days. In early 1933 Atalantas replaced the DH.66s on the Kisumu to Cape Town sector of the London to Cape Town route.[12] On 9 February 1936 the trans-Africa route was opened by Imperial Airways between Khartoum and Kano in Nigeria. This route was extended to Lagos on 15 October 1936.

Short Empire flying boats

In 1937 with the introduction of Short Empire flying boats built at Short Brothers, Imperial Airways could offer a through-service from Southampton to the Empire. The journey to the Cape was via Marseille, Rome, Brindisi, Athens, Alexandria, Khartoum, Port Bell, Kisumu and onwards by land-based craft to Nairobi, Mbeya and eventually Cape Town. Survey flights were also made across the Atlantic and to New Zealand. By mid-1937 Imperial had completed its thousandth service to the Empire. Starting in 1938 Empire flying boats also flew between Britain and Australia via India and the Middle East.[13]

In March 1939 three Shorts a week left Southampton for Australia, reaching Sydney after ten days of flying and nine overnight stops. Three more left for South Africa, taking six flying days to Durban.[14]

Passengers

Imperial's aircraft were small, most seating fewer than twenty passengers; about 50,000 passengers used Imperial Airways in the 1930s. Most passengers on intercontinental routes or on services within and between British colonies were men in colonial administration, business or research. To begin with only the wealthy could afford to fly, but passenger lists gradually diversified. Travel experiences related to flying low and slow, and were reported enthusiastically in newspapers, magazines and books.[15] There was opportunity for sightseeing from the air and at stops.[16]

Crews

Imperial Airways stationed its all-male flight deck crew, cabin crew and ground crew along the length of its routes. Specialist engineers and inspectors – and ground crew on rotation or leave – travelled on the airline without generating any seat revenue. Several air crew lost their lives in accidents. At the end of the 1930s crew numbers approximated 3,000. All crew were expected to be ambassadors for Britain and the British Empire.[15]

Air Mail

In 1934 the government began negotiations with Imperial Airways to establish a service (Empire Air Mail Scheme) to carry mail by air on routes served by the airline. Indirectly these negotiations led to the dismissal in 1936 of Sir Christopher Bullock, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Air Ministry, who was found by a Board of Inquiry to have abused his position in seeking a position on the board of the company while these negotiations were in train. The government, including the Prime Minister, regretted the decision to dismiss him, later finding that, in fact, no corruption was alleged and sought Bullock's reinstatement which he declined.[17]

The Empire Air Mail Programme started in July 1937, delivering anywhere for 11/2 d./oz. By mid-1938 a hundred tons of mail had been delivered to India and a similar amount to Africa. In the same year, construction was started on the Empire Terminal in Victoria, London, designed by A. Lakeman and with a statue by Eric Broadbent, Speed Wings Over the World gracing the portal above the main entrance. From the terminal there were train connections to Imperial's flying boats at Southampton and coaches to its landplane base at Croydon Airport. The terminal operated as recently as 1980.[18]

To help promote use of the Air Mail service, in June and July 1939, Imperial Airways participated with Pan American Airways in providing a special "around the world" service; Imperial carried the souvenir mail from Foynes, Ireland, to Hong Kong, out of the eastbound New York to New York route. Pan American provided service from New York to Foynes (departing 24 June, via the first flight of Northern FAM 18) and Hong Kong to San Francisco (via FAM 14), and United Airlines carried it on the final leg from San Francisco to New York, arriving on 28 July.

Captain H. W. C. Alger was the pilot for the inaugural air mail flight carrying mail from England to Australia for the first time on the Short Empire flyingboat Castor for Imperial Airways' Empires Air Routes, in 1937.[4]

In November 2016, 80 years later, the Crete2Cape Vintage Air Rally flew this old route with fifteen vintage aeroplanes – a celebration of the skill and determination of these early aviators.[19]

Second World War

Before the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939, the British government had already implemented the Air Navigation (Restriction in Time of War) Order 1939. That ordered military takeover of most civilian airfields in the UK, cessation of all private flying without individual flight permits, and other emergency measures. It was administered by a statutory department of the Air Ministry titled National Air Communications (NAC). By 1 September 1939, the aircraft and administrations of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd were physically transferred to Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, to be operated jointly by NAC. On 1 April 1940, Imperial Airways Ltd and British Airways Ltd were officially combined into a new company, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), that had already been formed on 24 November 1939 with retrospective financial arrangements.[20]

Accidents and incidents

1920s

- 24 December 1924: de Havilland DH.34 G-EBBX City of Delhi crashed and caught fire shortly after take-off from Croydon Airport, killing the pilot and all seven passengers.[6][21]

- 13 July 1928: Vickers Vulcan G-EBLB crashed at Purley during a test flight, killing four of the six people on board.[22] As a result of the crash, Imperial Airways stopped the flying of staff (so called joy rides) during test flights.

- 17 June 1929: Handley Page W.10 G-EBMT City of Ottawa ditched in the English Channel following engine failure whilst on a flight from Croydon to Paris with the loss of seven lives.[23]

- 6 September 1929: de Havilland Hercules G-EBMZ City of Jerusalem crashed and burned on landing at Jask, Iran in the dark due to the pilot misjudging the altitude and stalling the aircraft, killing three of five on board.[24]

- 26 October 1929: Short Calcutta G-AADN City of Rome force-landed off La Spezia, Italy in poor weather; the flying boat sank in the night during attempts to tow it to shore, killing all seven on board.[25][26]

1930s

- 30 October 1930: Handley Page W.8g G-EBIX City of Washington struck high ground in fog at Boulogne, Paris, France, killing three of six on board.[23][27]

- 28 March 1933: Armstrong Whitworth Argosy G-AACI City of Liverpool crashed at Diksmuide, Belgium following an in-flight fire. This is suspected to be the first case of sabotage in the air. All fifteen people on board were killed.[28]

- 30 December 1933: Avro Ten G-ABLU Apollo collided with a radio mast at Ruysselede, Belgium and crashed. All ten people on board were killed.[29]

- 31 December 1935: Short Calcutta G-AASJ City of Khartoum crashed off Alexandria, Egypt when all four engines failed on approach, possibly due to fuel starvation; twelve of 13 on board drowned when the flying boat sank.[26][30]

- 22 August 1936: Short Kent G-ABFA Scipio sank at Mirabello Bay, Crete after a heavy landing, killing two of 11 on board.[26][31]

- 24 March 1937: Short Empire G-ADVA Capricornus crashed in the Beaujolois Mountains near Ouroux, France, following a navigation error, killing five.[32]

- 1 October 1937: Short Empire G-ADVC Courtier crashed on landing in Phaleron Bay, Greece due to poor visibility, killing two of 15 on board.[33]

- 5 December 1937: Short Empire G-ADUZ Cygnus crashed on takeoff from Brindisi, Italy due to incorrect flap settings, killing two.[34]

- 27 July 1938: Armstrong Whitworth Atalanta G-ABTG Amalthea flew into a hillside near Kisumu, Kenya shortly after takeoff, killing all four on board.[35]

- 27 November 1938: Short Empire G-AETW Calpurnia crashed in Lake Habbaniyah, Iraq in bad weather after the pilot descended to maintain visual contact with the ground following spatial disorientation, killing all four crew.[36]

- 21 January 1939: Short Empire G-ADUU Cavalier ditched in the Atlantic 285 mi off New York due to carburettor icing and loss of engine power; three drowned while ten survivors were picked up by the tanker Esso Baytown. Thereafter Imperial Airways and Pan-American trans-oceanic flying boats had the upper surfaces of the wings painted with orange high visibility markings.

- 1 May 1939: Short Empire G-ADVD Challenger crashed in the Lumbo lagoon while attempting to land at Lumbo Airport, killing two of six on board.[37]

1940

- 1 March 1940: Flight 197,[38] operated by Handley Page H.P.42 G-AAGX Hannibal, disappeared over the Gulf of Oman with eight on board; no wreckage, cargo or occupants have been found. The cause of the crash remains unknown, but fuel starvation, a bird strike damaging a propeller and causing an engine or wing to separate, an in-flight breakup or multiple engine failure were theorized. Two months after the crash, the H.P.42 was withdrawn from passenger operations. It was also recommended that all commercial aircraft used in long flights over water be equipped with personal and group life saving gear; this would later become standard throughout the airline industry.

Non-fatal accidents

- 21 October 1926: Handley Page W.10 G-EBMS City of Melbourne ditched in the English Channel 18 nautical miles (33 km) off the English coast after an engine failed. All 12 people on board were rescued by FV Invicta.[23][39]

- 19 April 1931: de Havilland DH.66 Hercules with registration G-EBMW, damaged beyond repair in a forced landing following fuel starvation at Surabaya. The airplane operated on a trial mail flight from India to Melbourne with en route stops at Semarang, Soerabaja and Kupang.

- 8 August 1931: Handley Page H.P.42 G-AAGX Hannibal was operating a scheduled passenger flight from Croydon to Paris when an engine failed and debris forced a second engine to be shut down. A forced landing at Five Oak Green, Kent resulted in extensive damage. No injuries occurred. Hannibal was dismantled and trucked to Croydon to be rebuilt.[40]

- 9 November 1935: Short Kent G-ABFB Sylvanus caught fire and burned out during refueling in Brindisi Harbor; the refueling crew were able to jump clear of the burning aircraft and survived.[nb 1]

- 29 September 1936: Armstrong Whitworth Atalanta G-ABTK burned out in a hangar fire at Delhi, India.

- 31 May 1937: Handley Page H.P.45 (former H.P.42) G-AAXE Hengist was destroyed in a hangar fire at Karachi, India.[42]

- 3 December 1938: de Havilland Express G-ADCN burned out at Bangkok.

- 12 March 1939: Short S.23 Empire Flying Boat Mk 1 G-ADUY, damaged beyond repair at Tandjong, Batavia, Netherlands East Indies. Struck a submerged object while taxiing after alighting. Aircraft beached but damaged beyond repair by immersion and mishandling during salvage. Aircraft dismantled and shipped to England but not returned to service.[43]

- 7 November 1939: Handley Page H.P.42 G-AXXD Horatius was written off following a forced landing at a golf course at Tiverton, Devon.

- 19 March 1940: Handley Page H.P.45 G-AAXC Heracles and H.P.42 G-AAUD Hanno were written off after being blown over in a windstorm while parked at Whitchurch Airport.

Aircraft

Imperial Airways operated many types of aircraft from its formation on 1 April 1924 until 1 April 1940 when all aircraft still in service were transferred to BOAC.[44]

| Aircraft | Type | Number | Period | Names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong Whitworth Argosy Mk.I | landplane City class | 3 | 1926–34 | Birmingham (crashed 1931), City of Wellington (later City of Arundel) (1934), Glasgow (retired 1934) | [28][45] |

| Armstrong Whitworth Argosy Mk.II | 4 | 1929–35 | City of Edinburgh (wrecked 1926), City of Liverpool (wrecked 1933), City of Manchester (sold 1935) and City of Coventry (scrapped 1935) | [28][45] | |

| Armstrong Whitworth Atalanta[46] | landplane Atalanta class | 8 | 1932–41 | Atalanta (sold), Andromeda (withdrawn 1939), Arethusa (renamed Atalanta), Artemis, Astraea, Athena (burnt 1936), Aurora (sold) and Amalthea (wrecked 1938). | For Nairobi-Cape Town leg on South Africa route & Karachi-Singapore leg on Australia route.[12][46] |

| Armstrong Whitworth Ensign | landplane Ensign class | 12 | 1938–46 | Empire type (27 passengers) Ensign, Egeria, Elsinore, Euterpe, Explorer, Euryalus, Echo, Endymion and Western Type (40 passengers) Eddystone, Ettrick, Empyrean and Elysian | Everest & Enterprise delivered to BOAC. Intended to deliver 1st-class mail to the Empire by air.[44][45][47] |

| Avro 618 Ten[45] | landplane | 2 | 1930–38 | Achilles (crashed 1938)[45] Apollo (collided with radio mast 1933) | licence-built Fokker F.VII 3/m[29] |

| Avro 652 | 2 | 1936–38 | Avalon and Avatar (later Ava) to RAF in 1938.[45] | Prototypes for Anson bomber/trainer[29] | |

| Boulton & Paul P.71A | landplane Bodiciea class | 2 | 1934–36 | Bodiciea (lost 1935) and Britomart (lost 1936)[45] | Experimental mailplanes[48] |

| Bristol Type 75 Ten-seater | landplane | 2 | 1924–26 | G-EAWY, G-EBEV (retired 1925) | ex-Instone Air Line used as freighters |

| de Havilland DH.34 | 7 | 1924–26 | ex-Instone Air Line G-EBBR (wrecked 1924), G-EBBT (scrapped 1930), G-EBBV (scrapped 1926), G-EBBW (scrapped 1926) and ex-Daimler Airway G-EBBX (wrecked 1924), G-EBBY (scrapped 1926), G-EBCX (wrecked 1924) | [6] | |

| de Havilland DH.50 | 3 | 1924–33 | G-EBFO (damaged 1924 and sold), G-EBFP (scrapped 1933), G-EBKZ (crashed 1928) | G-EBFO used for surveys, later fitted with twin floats and sold in Australia[45] | |

| de Havilland Highclere | 1 | 1924–27 | G-EBKI | freighter, destroyed in hangar collapse | |

| de Havilland Giant Moth | 1 | 1930-30 | G-AAEV (wrecked 1930) | crashed in Northern Rhodesia 2 weeks after hand over. | |

| de Havilland Hercules | 9 | 1926–35 | City of Cairo (wrecked 1931), City of Delhi (to SAAF 1934), City of Baghdad (withdrawn 1933), City of Jerusalem, City of Tehran, City of Basra (to SAAF 1934), City of Karachi (withdrawn 1935), City of Jodhpur (sold) and City of Cape Town (sold)[45] | ||

| de Havilland Express[45] | landplane Diana class | 12 | 1934–41 | Daedalus (burned 1938), Danae, Dardanus, Delia (wrecked 1941), Delphinus, Demeter, Denebola, Dido, Dione, Dorado, Draco (wrecked 1935), and Dryad (sold 1938) | All surviving aircraft impressed in 1941 |

| de Havilland Albatross | landplane Frobisher class | 7 | 1938–43 | Faraday (impressed 1940), Franklin (impressed 1940), Frobisher (destroyed 1940), Falcon (scrapped 1943), Fortuna (crashed 1943), Fingal (crashed 1940) and Fiona (scrapped 1943).[45] | 1 used as long range mail carrier[49] |

| Desoutter IB | landplane | 1 | 1933–35 | G-ABMW | Air-taxi No 6 |

| Handley Page O/10 | 1 | 1924-24 | G-EATH | ex-Handley Page Transport but never used | |

| Handley Page W8b | 3 | 1924–32 | Princess Mary (wrecked 1928), Prince George (retired 1929) and Prince Henry (retired 1932)[23][45] | ex-Handley Page Transport[23] | |

| Handley Page W8f Hamilton | 1 | 1924–30 | City of Washington (wrecked 1930)[23][45] | Converted to twin engines and redesignated as W8g in 1929 | |

| Handley Page W9a Hampstead | 1 | 1926–29 | City of New York (sold 1929)[23][45] | ||

| Handley Page W.10 | 4 | 1926–33 | City of Melbourne (sold 1933), City of Pretoria (sold 1933), City of London (crashed 1926) and City of Ottawa (crashed 1929).[23][45] | ||

| Handley Page H.P.42E | landplane Hannibal class | 4 | 1931–40 | Hannibal (wrecked 1940), Horsa (impressed 1940), Hanno (wrecked 1940), Hadrian (impressed 1940) | (24 passengers) used on long "Empire" routes[42] |

| Handley Page H.P.42W/H.P.45 | landplane Heracles class | 4 | 1931–40 | Heracles (wrecked 1940), Horatius (wrecked 1939), Hengist (wrecked 1937) and Helena (impressed 1940) | (38 passengers) on short "Western" routes, Hengist and Helena converted to H.P.42E.[42] |

| Short S.8 Calcutta | flying boat | 5 | 1928–35 | City of Alexandria (wrecked 1936), City of Athens (later City of Stonehaven) (scrapped), City of Rome (wrecked 1929), City of Khartoum (wrecked 1935) and City of Salonica (later City of Swanage) (scrapped)[26] | |

| Short Kent | flying boat Scipio class | 3 | 1931–38 | Scipio (wrecked 1936), Sylvanus (burned 1935) and Satyrus (scrapped 1938)[26] | |

| Short Scylla | landplane | 2 | 1934–40 | Scylla (wrecked 1940) and Syrinx (scrapped 1940)[45] | Landplane version of Kent, replacement for lost H.P.42s.[50] |

| Short Mayo Composite | flying boat | 2 | 1938–40 | Mercury (scrapped 1941) and Maia (destroyed in German raid, 1942).[45] | Long range piggyback Composite aircraft derived from Short Empire. |

| Short S.26 Empire | flying boat C class | 31 | 1936–47 | Canopus, Caledonia, Centaurus, Cavalier, Cambria, Castor, Cassiopea, Capella, Cygnus, Capricornus, Corsair, Courtier, Challenger, Centurion, Coriolanus, Calpurnia, Ceres, Clio, Circe, Calypso, Camilla, Corinna, Cordelia, Cameronian, Corinthian, Coogee, Corio, and Coorong. Carpentaria, Coolangatta, Cooee delivered but not used, and transferred to Qantas | provided mail and passenger service to Bermuda, South Africa and Australia.[45][51][52] |

| Short S.26 | flying boat G class | 3 | 1939–40 | Golden Hind, Golden Fleece and Golden Horn | Built for trans-atlantic service, impressed by RAF before entering revenue service.[45] 2 returned to BOAC service and used until 1947. |

| Short S.30 Empire | flying boat C class | 9 | 1938–47 | Champion, Cabot, Caribou, Connemara, Clyde, Clare, Cathay, Ao-tea-roa (to TEAL as Aotearoa), Captain Cook (to TEAL as Awarua). | long range variant of S.23[45][51][52] |

| Supermarine Sea Eagle | flying boat | 2 | 1924–29 | Sarnia/G-EBGR (retired 1929) and G-EBGS (wrecked 1927) | ex-British Marine Air Navigation[45] |

| Supermarine Southampton | 1 | 1929–30 | G-AASH | RAF S1235 on loan for 3 months to replace crashed Calcutta on Genoa-Alexandria airmail run.[53] | |

| Supermarine Swan | 1 | 1925–27 | G-EBJY (scrapped 1927) | RAF prototype loaned for cross-Channel service | |

| Vickers Vanguard | landplane | 1 | 1926–29 | G-EBCP (wrecked 1929) | on loan from Air Ministry for evaluation |

| Vickers Vellox | 1 | 1934–36 | G-ABKY (wrecked 1936) | cargo/experimental flights.[45] Crashed at Croydon in August killing pilots and two wireless operators.[54] | |

| Vickers Vimy Commercial | 1 | 1924–25 | City of London (wrecked 1925) | ex-Instone Air Line[45][55] | |

| Vickers Vulcan | 3 | 1924–28 | G-EBLB/City of Brussels (wrecked 1928), G-EBFC (withdrawn 1924 unused), G-EBEK (loaned from Air Ministry for 1925 Empire Exhibition Display.[45]) | [22] | |

| Westland IV and Wessex | 3 | 1931–37 | G-AAGW, G-ABEG (wrecked 1936), G-ACHI | 2 leased to other operators. IV (G-AAGW) upgraded to Wessex.[56] | |

References

- Pirie, 2009

- Ord-Hume, 2010, pp.7–9

- Ord-Hume, 2010, p.10

- Bluffield, Robert (19 November 2014). Over Empires and Oceans: Pioneers, Aviators and Adventurers – Forging the International Air Routes 1918–1939. Tattered Flag. ISBN 9780954311568.

- Terms of Agreement Published Flight, 1924.

- Stroud, June 1984, pp. 315–19

- "Imperial Airways". Archived from the original on 11 November 2007.

- "Scheduled airliner flight when it was shown on the London-Paris route".

- "Sir Alan Cobham ; A Life of a Pioneering Aviator". RAF Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- "Sir Alan Cobham ; A Life of a Pioneering Aviator". RAF Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Stroud, Nov 1986, pp. 609–14

- Stroud, June 1986, pp.321–326

- Imperial Airways Timetable October 1938. London: Curwen Press. 1938. pp. 2–3.

- Imperial Airways Timetable April 1939. London: Curwen Press. 1939. p. 2.

- Pirie (2012)

- Pirie, G. H. (2009). "Incidental tourism: British imperial air travel in the 1930s". Journal of Tourism History. 1 (1): 49–66. doi:10.1080/17551820902742772. S2CID 144454885.

- Allaz, Camille (2005). History of Air Cargo and Airmail from the 18th Century. Gardners Books. p. 97. ISBN 0954889606.

- "The Imperial Airways Empire Terminal, Victoria, London". 8 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "CRETE2CAPE". VintageAirRally. 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Moss (1962)

- "Air Disaster at Croydon". Flight. No. 1 January 1925. p. 4.

- Stroud, Nov 1987, pp.609–612

- Stroud, Oct 1983, pp.535–539

- Accident description for G-EBMZ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-AADN at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Stroud, Feb 1987, pp.97–103

- Accident description for G-EBMZ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Stroud, May 1985, pp.265–269

- Stroud, Feb 1991, pp.115–120

- Accident description for G-AASJ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ABFA at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ADVA at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ADVC at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ADUZ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ABTG at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-AETW at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- Accident description for G-ADVD at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 18 January 2013.

- "Crash of a Handley Page H.P.42E into the Gulf of Oman, 8 killed". Bureau of Aircraft Accidents. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "ACCIDENT DETAILS". Plane Crash Info. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Accident To Air Liner. Damaged in Forced Landing". The Times. No. 45897. London. 10 August 1931. col G, p. p10.

- "Crash of a Short S.17 Kent in Brindisi: 12 killed". Bureau of Aircraft Accidents. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Stroud, Aug 1985, pp.433–437

- ASN Aircraft accident Short S.23 Empire Flying Boat Mk I G-ADUY Tandjong, Batavia, Java (Netherlands East Indies)

- Jackson, 1973, pp.55–57

- Bluffield 2009, pp. 211–213

- Jackson, 1973, pp.52–54

- Stroud, June 1988, pp.433–437

- Stroud, Aug 1986, pp.433–436

- Jackson, 1973, 433–437

- Stroud, Oct 1984, pp.549–553

- Stroud, Dec 1989, pp.763–769

- Stroud, Jan 1990, pp.51–61

- Jackson, 1974, p.443

- "Commercial Aviation" Flight 13 August 1936 p181

- Stroud, Feb 1984, pp.101–105

- Stroud, Dec 1985, pp.657–661

Footnotes

Notes

- One source states the aircraft caught fire before takeoff with 12 killed.[41]

Bibliography

- Baldwin, N.C. 1950.Imperial Airways (and Subsidiary Companies): A History and Priced Check List of the Empire Air Mails. Sutton Coldfield, England: Francis J. Field.

- Bluffield, Robert (2009). Imperial Airways – The Birth of the British Airline Industry 1914–1940. Hersham, Surrey, England: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906537-07-4.

- Budd, Lucy "Global Networks Before Globalisation: Imperial Airways and the Development of Long-Haul Air Routes" Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Research Bulletin 253, 5 December 2007.

- Cluett, Douglas; Nash, Joanna; Learmonth Bob. 1980. Croydon Airport 1928 – 1939, The Great Days. London Borough of Sutton ISBN 0-9503224-8-2

- Davies, R.E.G 2005. British Airways: An Airline and Its Aircraft, Volume 1: 1919–1939—The Imperial Years. McLean, VA: Paladwr Press. ISBN 1-888962-24-0

- Doyle, Neville. 2002. The Triple Alliance: The Predecessors of the first British Airways. Air-Britain. ISBN 0-85130-286-6

- Higham, Robin. 1960. Britain's Imperial Air Routes 1918 to 1939: The Story of Britain's Overseas Airlines London: G.T. Foulis; Hamden, CT: Shoe String.

- Jackson, A.J. 1959 and 1974. British Civil Aircraft since 1919 2 vols (1st ed.); 3 vols (2nd ed.) London: Putnam.

- Moss, Peter W. 1962. Impressments Log (Vol I-IV). Air-Britain.

- Moss, Peter W. October 1974. British Airways. Aeroplane Monthly.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. (2010). Imperial Airways, From Early Days to BOAC. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 9781840335149. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Pirie, G.H. 2004. Passenger traffic in the 1930s on British imperial air routes: refinement and revision. Journal of Transport History, 25: 66–84.

- Pirie, G.H. 2009. Air Empire: British Imperial Civil Aviation 1919–39. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4111-2.

- Pirie, G.H. 2009. Incidental tourism: British imperial air travel in the 1930s. Journal of Tourism History, 1: 49–66.

- Pirie, G. H. (2012). Cultures and Caricatures of British Imperial Aviation: Passengers, Pilots, Publicity. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8682-3.

- Pudney, J. 1959. The Seven Skies – A Study of BOAC and its forerunners since 1919. London: Putnam.

- Salt, Major A.E.W. 1930.Imperial Air Routes. London: John Murray.

- Sanford, Kendall C. 2003. Air Crash Mail of Imperial Airways and Predecessor Airlines. Bristol: Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund. ISBN 0-9530004-6-X

- Stroud, John 1962.Annals of British and Commonwealth Air Transport 1919–1960. London: Putnam.

- Stroud, John. 2005. The Imperial Airways Fleet. Stroud, England: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2997-3

- Stroud, John (May 1985). "Wings of Peace (Armstrong Whitworth Argosy)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 265–269.

- Stroud, John (June 1986). "Wings of Peace (Armstrong Whitworth A.W.XV Atalanta)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 321–326.

- Stroud, John (July 1988). "Wings of Peace (Armstrong Whitworth A.W.27 Ensign)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 433–437.

- Stroud, John (February 1991). "Wings of Peace (Avro Monoplanes)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 115–120.

- Stroud, John (August 1986). "Wings of Peace (Boulton Paul P.64 and P.71A)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 433–436.

- Stroud, John (June 1984). "Wings of Peace (De Havilland DH.34)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 315–319.

- Stroud, John (November 1986). "Wings of Peace (De Havilland DH.66 Hercules)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 609–614.

- Stroud, John (June 1990). "Wings of Peace (De Havilland Albatross part 1)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 369–372.

- Stroud, John (July 1990). "Wings of Peace (De Havilland Albatross part 2)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 433–437.

- Stroud, John (October 1983). "Wings of Peace (Handley Page Type W & derivatives)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 535–539.

- Stroud, John (August 1985). "Wings of Peace (Handley Page H.P.42 and H.P.45)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 433–437.

- Stroud, John (February 1987). "Wings of Peace (Short S.8 Calcutta & S.17 Kent)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 97–103.

- Stroud, John (October 1984). "Wings of Peace (Short L.17 Scylla)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 549–553.

- Stroud, John (December 1989). "Wings of Peace (Short Empire flying-boats part 1)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 763–769.

- Stroud, John (January 1990). "Wings of Peace (Short Empire flying-boats part 2)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 51–61.

- Stroud, John (November 1987). "Wings of Peace (Vickers Vulcan)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 609–612.

- Stroud, John (February 1984). "Wings of Peace (Vickers Vimy Commercial)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 101–105.

- Stroud, John (December 1985). "Wings of Peace (Westland IV and Wessex)". Aeroplane Monthly. Kelsey. pp. 657–661.

External links

- www.imperial-airways.com enthusiast website at archive.org

- British Airways "Explore our past"

- Imperial Airways Timetables

- History Imperial Airways Eastern Route

- Website for historical information on the airline

- Website for the Imperial Airways Museum

- Website for The Crete2Cape Vintage Air Rally

- Documents and clippings about Imperial Airways in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Egypt And Back With Imperial Airways in the East Anglian Film Archive