Hurricane Fred (2015)

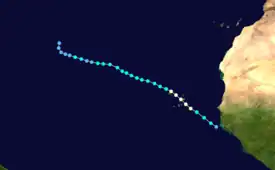

Hurricane Fred was the easternmost Atlantic hurricane to form in the tropics, and the first to move through Cape Verde since 1892.[1] The second hurricane and sixth named storm of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season, Fred originated from a well-defined tropical wave over West Africa in late August 2015. Once offshore, the wave moved northwestward within a favorable tropospheric environment and strengthened into a tropical storm on August 30. The following day, Fred grew to a Category 1 hurricane with peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) as it approached Cape Verde. After passing Boa Vista and moving away from Santo Antão, it entered a phase of steady weakening, dropping below hurricane status by September 1. Fred then turned to the west-northwest, enduring increasingly hostile wind shear, but maintained its status as a tropical cyclone despite repeated forecasts of rapid dissipation. It fluctuated between minimal tropical storm and tropical depression strength through September 4–5 before curving sharply to the north. By September 6, Fred's circulation pattern had diminished considerably, and the storm dissipated later that day.

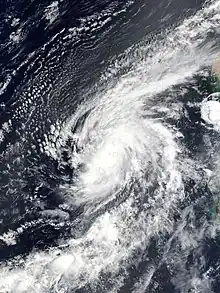

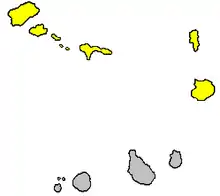

Fred over the Cape Verde Islands on August 31 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 30, 2015 |

| Dissipated | September 6, 2015 |

| Category 1 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 85 mph (140 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 986 mbar (hPa); 29.12 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 9 direct |

| Damage | $2.5 million (2015 USD) |

| Areas affected | West Africa, Cape Verde |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Under threat from the hurricane, all of Cape Verde was placed under a hurricane warning for the first time in the nation's history. Gale-force winds battered much of the Barlavento region throughout August 31, downing trees and utility poles. On the easternmost islands of Boa Vista and Sal, Fred leveled roofs and left villages without power or phone services for a few days. About 70 percent of the houses in Povoação Velha suffered light to moderate damage. Across the northernmost islands, rainstorms flooded homes, washed out roads, and ruined farmland; São Nicolau endured great losses of crops and livestock. Material damage across Cape Verde totaled US$2.5 million,[nb 1] though the rain's overall impact on agriculture was positive and replenishing. Swells from the hurricane produced violent seas along the West African shoreline, destroying fishing villages and submerging swaths of residential areas in Senegal. Between the coasts of West Africa and Cape Verde, maritime incidents related to Fred resulted in nine deaths.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

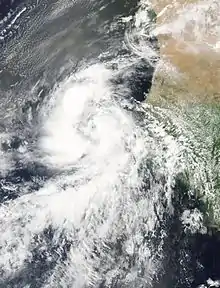

Early on August 28, the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring an unusually vigorous tropical wave—an elongated area of low air pressure—inland over West Africa.[1][3] Trailed by widespread cloudiness, the wave tracked toward the open Atlantic as it developed a broad cyclonic rotation within the lower atmosphere near Guinea's coastline.[4] The disturbance veered toward the northwest and entered the ocean off Conakry around 18:00 UTC, August 29. By that time, the NHC was predicting favorable conditions for the development of a tropical cyclone within the next 48 hours.[5] Strong thunderstorms thrived overnight and consolidated near a well-defined low-pressure center;[6][7] around midnight August 30, satellite images and scatterometer data confirmed that a tropical depression with sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) had formed about 300 miles (480 km) west-northwest of Conakry.[1][8]

Although tropical cyclones in the extreme eastern Atlantic are typically propelled westward by high pressures from the North Atlantic subtropical ridge,[9] this depression took an atypical northwestward path along a breach in the ridge from a previous disturbance.[1][8] Its cyclonic structure steadily improved as a sharply curved rainband tightened around the center, resembling the precursor to an eye.[10] At 06:00 UTC on August 30, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Fred while 390 mi (625 km) east-southeast of Praia, Cape Verde[1]—among the four easternmost locations for a tropical storm to form since modern record-keeping began in 1851.[10] A steady trend of intensification ensued while Fred moved through a region with ample tropical moisture, light upper winds, and above-average sea surface temperatures.[11] The storm developed a thick, circular central dense overcast with good outflow, and the eye feature became well established at all levels of the circulation.[12][13] Based on these characteristics, as well as satellite intensity estimates of 75 mph (120 km/h) winds, Fred was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane at 00:00 UTC, August 31. Then centered 165 mi (270 km) east-southeast of Sal, Cape Verde,[1] it became the easternmost tropical cyclone ever to attain hurricane status in the tropical Atlantic.[nb 2][15]

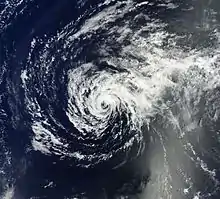

A compact cyclone, Fred quickly reached its peak strength as a hurricane, with a minimum central pressure of 986 mbar (hPa; 29.12 inHg) and 85 mph (140 km/h) winds.[1] Through the rest of August 31, the hurricane traversed the Barlavento Islands of Cape Verde, barely skirting the southern coast of Boa Vista around 12:00 UC.[16] Gradually decreasing in definition, the eye passed north of São Nicolau and then north-northeast of Santo Antão over the next 12 hours.[17][18] On September 1, drier air and stronger wind shear aloft dispersed the convection around the cyclone's core, causing Fred to diminish to a tropical storm.[19] The weakened storm turned slightly toward the west-northwest, over considerably cooler waters, in response to high pressure rebuilding to its north.[20][21] Through much of September 1–4, Fred produced limited convective activity, with intermittent flares of thunderstorms that were continuously blown away from the center by the strong upper winds. Despite the adverse environment and the storm's lack of stable convection, Fred maintained a robust spiral of low-level clouds and gales during this period, defying the NHC's repeated forecasts of its dissipation.[22]

At 12:00 UTC on September 4, the NHC downgraded Fred to a tropical depression as its wind circulation waned; though its winds briefly picked up back to tropical storm force the next day, Fred continued as a depression with minimal convection throughout the remainder of its existence.[1] Concurrently, a deep-altitude disturbance a few hundred miles east of Bermuda began to erode the southern edge of the high-pressure ridge that Fred had circumnavigated for most of its journey.[23] This changed the steering pattern in the region, turning the depression abruptly to the north on September 6.[23][24] Over the next hours, Fred became increasingly diffuse because of its progressively worsening surroundings.[25] It officially lost its status as a tropical cyclone at 18:00 UTC on September 6, degenerating into a surface trough about 1,200 mi (1,950 km) to the southwest of the Azores before merging with the disturbance off Bermuda.[1]

Preparations and impact

West Africa

Swells from Fred reached wide stretches of the West African coastline, stirring up high seas as far north as Senegal. Along the shorelines between Dakar and M'Bour, rough surf devastated entire fishing districts and harbor towns, stranding boats and damaging roads and bridges. About 200 houses were demolished in the district of Hann, many of which experienced total wall collapse; dwellings in the town of Bargny endured similar destruction.[26][27] In the suburb of Rufisque, the waves overtopped dams, entered homes and cemeteries, and destroyed a mosque.[28] Several villages outside the capital area were completely cut off from their surroundings.[28] Victims across the affected region received more than 100 tons (220,000 lbs) of rice and 12 million CFA francs (US$20,000) in government relief funds.[29]

Farther south, in Guinea-Bissau, a storm surge flooded roads and low-lying establishments, such as offices and military barracks. The sea water submerged vast amounts of cropland in the Tombali Region, resulting in great losses of rice.[30] Offshore, waves as high as 23 feet (7 m) capsized a fishing boat with a crew of 19; twelve members were rescued, but the remaining seven disappeared at sea and were presumed dead.[31]

Cape Verde

A tropical storm warning was issued for Cape Verde upon the storm's formation, as well as a hurricane watch in light of forecasts of additional intensification. When Fred showed definitive signs of strengthening, the alerts were replaced by a hurricane warning,[1] marking the first occasion of a hurricane-level advisory in the nation's history.[32] On the morning of August 31, TACV Cabo Verde Airlines suspended its flights from the capital of Praia to Dakar;[33] all operations at the airports of Boa Vista, Sal, and São Vicente were halted when squalls began to spread across the islands.[34] Officials urged shipping interests on all islands to secure their vessels and remain in port.[35] A national music festival was canceled in Porto Novo, on the northernmost island of Santo Antão.[36]

Throughout Cape Verde, Hurricane Fred displaced more than 50 families[37] and caused CVE$250 million ($2.5 million) in damage,[27][38] primarily to the agricultural and private sectors of the Barlavento Islands.[37] It was the first hurricane to move through Cape Verde with a documented impact,[nb 3] as well as the nation's only record of onshore hurricane-force winds.[27] Although there were no casualties on land,[37] two fishermen navigating through the storm never returned to port in Boa Vista and were presumed dead.[39] Despite the losses in crops and livestock in the Barlavento region, the rainfall from Fred had a generally positive effect on the large-scale agriculture of Cape Verde, refilling rivers and reservoirs and irrigating drought-stricken farmland across the Sotavento Islands.[40][41]

Barlavento Islands

Traversing the eastern islands on the afternoon of August 31, Fred brought strong thunderstorms with 60 mph (100 km/h) winds and 3.8 inches (96 mm) of rain to Boa Vista, uprooting trees, damaging roofs and plaster, and knocking out power to most of the population.[27][42] The winds toppled a transmission tower in Sal Rei, disrupting cellphone services.[27][42] Two inhabitants were taken to hospital for non-critical injuries after their home had partially collapsed.[34] Floods swept through low-lying areas of Rabil and cut off the main road to surrounding towns, hampering emergency workers.[42][43] The southern village of Povoação Velha bore the brunt of the storm; about 70 percent of the houses there experienced some degree of damage, from broken tiles and windows to crumbled walls,[44] with repair costs of CVE$3 million (US$30,000).[45] A compromised infrastructure left the village without power and telephone services for five days.[44] Throughout Boa Vista, estimated losses from Fred totaled CVE$76 million ($760,000), including CVE$26 million ($260,000) in restoration costs.[43]

Similar conditions occurred in parts of Sal. Along the island's southern shore, Fred's storm surge sunk or stranded dozens of vessels and destroyed the island's main tourist pier in Santa Maria.[46] Restoration efforts had not yet been completed by May 2017, about 1.5 years after the hurricane; the delay led to concerns over the island's precarious, tourism-reliant economy.[47][48] Hotels, restaurants, and beach facilities were flooded, and roads in the town became impassable. Gusts leveled the roof of a high school gym,[42] which had initially been set up as a storm shelter to 100 citizens.[46] Elsewhere on the island, the winds knocked out power to homes in Palmeira,[42] and caused minor structural damage to Sal International Airport.[49] At the height of the storm, floods forced nearly 130 people living in the impoverished outskirts of Terra Boa and Espargos to relocate to shelters.[42][50] Fred destroyed 80 percent of the Loggerhead sea turtle nests on the beaches of Sal, crucial nesting sites for the species.[51] Overall, the hurricane left CVE$30 million ($300,000) in damage across Sal.[27]

Fred produced strong winds and downpours across the mountainous northern islands of Barlavento. São Nicolau experienced sustained hurricane-force winds of 80 mph (130 km/h)—the highest official wind speed recorded during hurricane. Rainfall there was moderate, peaking at 3.5 in (90 mm) at Juncalinho.[27] The blustery weather uprooted many old trees, triggered landslides, and left the villages on the island without power.[27][52] The strong winds downed power poles and wrecked the roof of a church in the village of Cabeçalinho.[53] In Ribeira Brava, São Nicolau's most populous town, the storm damaged 70 homes, destroyed greenhouses, and leveled a farmhouse, leaving some families homeless and others without a source of income.[54] In Carriçal, the torrential rainfall flooded homes, washed out roads, and ruined fruit and hydroponic crops.[55] Much of São Nicolau's livestock, including cattle from Hortelã, was lost in the storm.[53][56] Damage to agriculture—primarily banana and sugarcane[52]—and private property on the island reached CVE$50 million ($500,000).[27]

On the neighboring islands of São Vicente and Santo Antão, the storm's impact was limited to power outages, floods, and damaged crops.[57] Santo Antão recorded light winds and 8 in (200 mm) of rain,[41] although higher elevations received greater quantities.[27] In Porto Novo, 35 people were relocated as floods swept through neighborhoods.[58] The rain washed out the island's carrot, cabbage, and tomato plantations, especially in the vicinity of Alto Mira.[59] On São Vicente, roads were closed in and around Laginha. Gusts toppled two trees, one striking a car and lightly injuring the driver.[60] Hurricane-related costs for the two islands, mainly infrastructural repair, totaled CVE$16 million ($160,000).[27]

Sotavento Islands

The impact of Fred on the Sotavento region was relatively minor. The storm's outer bands dropped heavy rain on the islands of Santiago and Fogo, peaking at 13 in (330 mm) in the mountains of Santiago and causing flood damage to roads, sidewalks, and walls.[27] In São Miguel, on the former island, flood waters and fallen trees led to major traffic obstructions.[61] Structural damage across Santiago, mostly due to urban flooding, reached CVE$87 million ($860,000).[27] Conversely, the rains replenished dried-up water resources; a large reservoir in São Salvador do Mundo was filled to maximum capacity, irrigating adjacent arable lands.[40]

Notes

- All damage totals are in 2015 values of their respective currencies; currency conversions to USD were done via XE.com.[2]

- Although Fred was the easternmost hurricane in the tropical Atlantic, Hurricane Pablo in 2019, which formed in the subtropics, was the easternmost Atlantic hurricane overall.[14]

- Although a tropical cyclone in 1892 moved between the Cape Verde Islands and became a hurricane south of São Nicolau, it remained over water with very minimal effects on land.[27]

See also

- Timeline of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season

- List of West Africa hurricanes

- Hurricane Debbie (1961) – moved through Cape Verde before becoming a hurricane

- Hurricane Fred (2009) – moved south of Cape Verde before becoming one of the easternmost major hurricanes

References

- Beven, Jack (2016-01-20). Hurricane Fred (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "XE Currency Charts: USD to CVE". XE. 2015. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-08-28). Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Rivera-Acevedo, Evelyn (2015-08-29). Tropical Weather Discussion (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Rubio, Gladys (2015-08-29). Tropical Weather Discussion (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Rubio, Gladys (2015-08-30). Tropical Weather Discussion (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Kimberlain, Todd (2015-08-30). Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-08-30). Tropical Depression Six Special Discussion Number One (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Landsea, Chris (2012-06-01). "A2: What is a "Cape Verde" hurricane?". In Landsea, Chris; Dorst, Neal (eds.). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.8. Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-08-30). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Two (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Brown, Daniel (2015-08-30). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Three (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- Pasch, Richard (2015-08-31). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Five (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-08-31). Hurricane Fred Discussion Number Six (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- Bevan, John (2020-01-27). Hurricane Pablo (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- "Fred is easternmost hurricane to form in tropics of Atlantic". The Washington Times. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. 2015-08-31. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Brown, Jack (2015-08-31). Hurricane Fred Discussion Number Seven (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Brown, Jack (2015-08-31). Hurricane Fred Discussion Number Eight (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Pasch, Richard (2015-08-31). Hurricane Fred Intermediate Advisory Number Eight A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Pasch, Richard (2015-09-01). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Nine (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-09-01). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Ten (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- Brown, Daniel (2015-09-01). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Eleven (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- Beven, Jack (2015-09-02). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Thirteen (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- Stewart, Stacy (2015-09-03). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Eighteen (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- Beven, Jack (2015-09-04). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Twenty-Two (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- Brennan, Michael (2015-09-05). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Twenty-Six (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- Brown, Daniel (2015-09-06). Tropical Depression Fred Discussion Number Thirty (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- Canglialosi, John (2015-09-06). Tropical Depression Fred Discussion Number Thirty-One (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- "Sénégal: 200 maisons détruites par la houle à Dakar". StarAfrica (in French). Africa Press Agency. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-09-03. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- Jenkins, Gregory S.; Brito, Ester; Soares, Emanuel; Chiao, Sen; Lima, Jose Pimenta; Tavares, Benvendo; Cardoso, Angelo; Evora, Francisco; Monteiro, Maria (2017). "Hurricane Fred (2015): Cape Verde's First Hurricane in Modern Times, preparation, observations, impacts and lessons learned". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 98 (12): 2603–18. Bibcode:2017BAMS...98.2603J. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0222.1.

- Seck, Ndèye Binta; Diallo, Ibrahima; Ndiaye, Fatou; Thiam, Moussa; Gueye, Daouda; Niébé Ba, Samba (2015-09-01). "Avancée de la mer, houles dangereuses sur le littoral – Le diktat des vagues aux populations des zones cotières". Sud Quotidien (in French). Dakar, Senegal. Archived from the original on 2015-09-13. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- Kande, Aliou (2015-09-03). "Après les dégats causés par la houle: Le Premier ministre apporte soutien et réconfort". Le Soleil (in French). Dakar, Senegal. African Media Agency. Retrieved 2015-09-16. Republished by Dakaractu.

- "Efeitos de ciclone tropical em Cabo Verde atingem a Guiné-Bissau". Luanda Digital (in Portuguese). Luanda, Angola. Portuguese News Network. 2015-08-31. Retrieved 2015-09-02. Republished by Angola Formativa.

- "Seven fishermen killed by Hurricane Fred". Jamaica Observer. Kingston, Jamaica. Agence France-Presse. 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- "Primeiro furacão da história, "Fred" ameaça Cabo Verde" (in Portuguese). São Paulo, Brazil: De Olho No Tempo Meteorologia. 2015-08-30. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- "Furacão "Fred" obriga TACV a cancelar voo Praia-Dakar". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-08-31. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- "Recorde os principais momentos da passagem do furacão Fred por Cabo Verde". Expresso das Ilhas (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-08-31. Archived from the original on 2015-09-02. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "São Vicente: Navios interditos de sair para o mar – situação tenderá a agravar-se, segundo a AMP". Sapo Notícias (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-08-31. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- "Porto Novo: Previsão de mau tempo obriga edilidade a cancelar festival de Curraletes". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-08-30. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- "Furacão Fred desalojou 50 famílias e causou estragos em todo o país". Sapo Notícias (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Lusa News Agency. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Fred e chuvas deixaram prejuízos de 250 milhões de escudos". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-11-15. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- "Pescadores desaparecidos: Polícia Marítima da Praia fala em falta de informação". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-09-08. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "Chuvas fazem transbordar barragens de Faveta e de Canto de Cagarra". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-09-02. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- dos Santos, Nélio (2015-09-07). "Um verde que renasce do Furacão Fred" (in Portuguese). Bonn, Germany: Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- Fonseca, Sanny (2015-08-31). "Furacão "Fred" causa estragos na Boa Vista e no Sal". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- "Nota de Imprensa – Passagem do Furacão Fred" (PDF) (Press release) (in Portuguese). Sal Rei, Boa Vista: Câmara Municipal da Boavista. 2015-09-07. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Fonseca, Sanny (2015-09-04). "Boa Vista: Furacão Fred deixa 50 casas destruídas em Povoação Velha". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "Boa Vista: Recuperação de habitações de povoações velha danificadas pelo furacão Fred orçada em 3 mil contos" (Video) (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde: Radiotelevisão Caboverdiana. 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- "Furação Fred obrigou à evacuação de 120 pessoas em Cabo Verde". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese). Porto, Portugal. 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- "Um ano depois do furacão Fred: Pontão de Santa Maria ainda aguarda intervenções". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-08-09. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- Coelho, Gisela (2017-05-22). "Sal: apanha e falta de areia ameaçam sustentabilidade da economia turística e ambiental". A Nação (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- "llha do Sal foi uma das mais fustigadas pelo Furacão Fred" (in Portuguese). Macedo de Cavaleiros, Portugal: Rádio Onda Livre. 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "Sal: Destruição do Pontão foi a situação mais crítica provocada pelo furacão "Fred" – vereador" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-12-04. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Hazevoet, Cornelis J., ed. (November 2015). "Furação Fred destrói 80% dos ninhos das tartarugas marinhas" (PDF). A Cagarra: Newsletter of the Zoological Society of Cape Verde (Newsletter) (in Portuguese). No. 11. São Vicente, Cape Verde: Sociedade Caboverdiana de Zoologia. p. 5. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- "Agricultores de Fajã somam prejuízos com passagem do furação Fred". Ocean Press (in Portuguese). Santa Maria, Cape Verde. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- JSN, ed. (2015-09-01). "Fred – Proteção Civil em São Nicolau trabalhou na prevenção". Jornal de São Nicolau (in Portuguese). Tarrafal, Cape Verde. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Furacão Fred: Danos em São Nicolau rondam 10 mil contos". A Nação (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-09-02. Archived from the original on 2015-09-12. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- "Furacão Fred: Governo vai precisar de 30 mil contos para intervenções em São Nicolau" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-09-08. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- "Ministra do Desenvolvimento Rural São Nicolau para se inteirar dos estragos causados pelo furacão "Fred"" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde: Inforpress. Associated Press. 2015-09-07. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- "Fred: Proteção Civil faz balanço da passagem do furacão pelo arquipélago". Jornal de São Nicolau (in Portuguese). Tarrafal, Cape Verde. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2018-04-07. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Porto Novo: Vias de acesso afectadas pelo "Fred" começam a ser desobstruidas". A Semana (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. 2015-09-03. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Santo Antão: Agricultores de Alto Mira querem apoio do MDR para compensar estragos nas culturas" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-09-09. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Furacão: "Fred" poupou São Vicente – ilha registou queda de duas árvores, vento e chuva mansa" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-12-04. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "São Miguel: Autarquia precisa de cerca de 2,000 contos para fazer face aos estragos do furacão "Fred"". Sapo Noticías (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. 2015-09-02. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Fred

- The National Hurricane Center's Tropical Cyclone Report on Hurricane Fred