Hunnic art

Hunnic art covers all forms of art produced by the Huns, an extinct Central/Eastern Asian people, during their stay in Europe between c. 370 and c. 470 AD.

Hunnic art consists chiefly of cauldrons, vessels, and jewelry, with necklaces, fibulae and bracalets. The motifs on such items often represent animals, as well as trees and geometric patterns. Hunnic art had a deep influence on Germanic and more generally European art, causing a shift away from the Greco-Roman model. Hunnic art was itself informed by Chinese and especially Persian (East Iranian) art.

History

Examples of early Saka-Hunnic art include diadems found in Kanattas, near Lake Balkash. Lake Balkash is located in eastern Kazakhstan, in the homeland of the European Huns. Similar items have been discovered in Ukraine and Hungary. These items are also historically important as they reflect the westward Hunnic migration.[1]

Hunnic art was expressed in the forms of cauldrons, vessels, and jewelry, such as necklaces and bracelets, which the Huns introduced among the Germanic peoples. Typical features of Hunnic art include the use of gold, garnets, and granulation.[1] Numerous gold diadems were discovered in the graves of Hunnic women.[2]

Hunnic motifs typically consist of geometric patterns, trees and animals, such as horses, deers, cicadas and birds of prey.[1] The National Hungarian Museum has a fine example of golden fibula in the form of a cicada with garnets, and there are other such items in silver, while others still are completely made of gold.[1]

Hunnic art had an influence on the peoples with whom the Huns interacted in Europe, for example the Visigoths and the Gepids, among whom the Hunnic bronze mirror became widespread.[3][4] The Burgundians and the Franks also imitated the art and dresses of the royal Hunnic court. Likewise, the Hunnic weapons had an influence over the Alemanni and other Germanic peoples. Thus the Hunnic eastern Inner Asian art had a critical influence on the Middle Ages' Germanic art. Musset asserted that the Hunnic (and later Germanic) invasions brought about a shift in European art, which embraced oriental influences, shifting away from the Greco-Roman model via the Hunnic art, which was itself strongly influenced by the Persian/ Eastern Iranian art.[4]

Cauldrons

Cauldrons are an archaeological marker of the presence of the Huns.[5] They ultimately derive from the cauldrons of the Xiongnu. Not only the Xiongnu cauldrons and those of the Huns are virtually identical, but they were also found in similar locations (e.g. on banks of rivers), which also proves continuity of rituals.[6] Though some historians note that there are some artistic differences between the old Xiongnu cauldrons and the "new" cauldrons produced by the Huns, the finding of these cauldrons in the Altai region archaeologically proves at least that some Huns lived for a time on the flanks of the Altai mountains before migrating further west, as confirmed by the Wei Shu, stating that in the 5th century some remnants of the Xiongnu still lived in this region.[7]

The Huns/Xiongnu used these cauldrons for cooking, ritual purposes or both. The Hunnish cauldrons are bell shaped, they have generally squared handles and mushroom-like ornaments.[8]

Hunnic cauldrons (from the Hun period) may be used to trace the Hunnic migration from the east to the west. Examples were found as far west as Germany and France, and as far east as Kyzyl-Adyr, Lipnyagova, and Xinjiang, China. The Nanshan cauldron is noted for its typical Hunnish triangular motifs on the sides, similar to the examples with rectangular handles from Soka and Verkhniy Konets. Its best counterparts are however the examples with curved handles (appearing in the Don area, the Lower Danube region, plus the cauldron from Kyzyl-Adyr), as well as the Carpathian basin cauldrons with cloison-like cells below the rim. It alternates rectangular and triangular cells below the rim. Another typical Hunnish feature are its mushroom-like adornments by the handles. It has been postulated that, rather than being an early example of the later Hunnish style, this cauldron was taken back to Xinjiang from Europe.[9][10] The Nanshan cauldron, with its affinities to both the rectangular-handled cauldrons and those with rounded handles, reflects the fluidity of the boundary between the two types. The Nanshan site is located in Ürümqi, Xinjiang, China. The Kyzyl-Adyr cauldron, made of copper, is considered a transition between the Sarmatian-period and Hun-period cauldrons with mushroom-like handles.

The use of mushroom-like figures to decorate vessels, especially with ritual purposes, was typical of Chinese art, starting from the Shang dynasty.[11] Another characteristic of the Hunnish cauldrons is the use of the so-called "pendula" motifs. These motifs, imitating pendant tassels or borders, are thought by most historians to derive from textiles, or possibly leatherwork. Such pendants, too, appear on Chinese bronze vessels.[9] More specifically, they are particular of the Chinese Neolithic period, and Zoltán Takáts (Takács) considered them a direct derivation from them.[12] According to István Bóna, "the [Hunnic] cauldrons represented the direct embodiment of Chinese and Inner Asian bronzeworking," thus, the Hunnic cauldron had a "direct Chinese ancestry."[9] This assumption superseded the view of previous scholarship, tentatively linking the Hunnic cauldrons to the Sarmatian and Scythian cauldrons.[9] Bóna's assumption is supported by the Hungarian research, who regards it as the most authoritative on the matter.[9] The best analogies to Hunnnic cauldrons are Mongolian and Northern Chinese cauldrons with open-work foot.[9]

The mushroom shapes are typical of the late Hunnic period (during which the Huns/Xiongnu moved to Europe), differentiating the cauldrons of this period from most of the otherwise nearly identical Xiongnu period cauldrons. A bronze fragment of a Hun cauldron depicting a mushroom was found, together with two "clearly Hun" ceramic specimens, in the Lower Amu Darya, in the land of the Hephthalites, thus confirming the Chinese sources claiming that their land became Hunnic (i.e. Xiongnu).[13]

Apart from a "few brief overviews of manufacturing techniques" there have been no concrete studies on the manufacturing technique of the Hun cauldrons. Bóna believed that the cauldrons were cast in several pieces that were then soldered together with the foot riveted to the cauldron. He also emphasized the Chinese direct link for the casting technology.[9] The cauldrons were often deliberately damaged or broken into pieces, which Bóna linked to Chinese and Inner Asian customs.[9]

In the Yenisei region there are rock carvings depicting the ritual use of the cauldrons. These petroglyphs are difficult to date, but are often cited in the assessment of the ritual function of the Hunnic cauldrons. It is not excluded that the depicted rites were funerary. Takács, citing Chinese sources and analogies, believed they depicted bloody animal sacrifices.[9]

Turul

Several objects with representations of a bird of prey (possibly an eagle, an hawk, a falcon, a kite, or a vulture) were found in 4th and 5th-century Hunnic tombs. According to Werner these are eagle heads, while Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen preferred to call them "beak heads", as the animal represented could be any of several birds of prey, not necessarily an eagle.[14] Further, the Turul is a bird of prey often associated with Attila[15] and more generally the Huns, with diverse folk legends considering it the representation of their nation. In Hungarian chronicles, the Turul is also considered the ancestor of the Hungarian rulers, the Árpád dynasty. According to Simon of Kéza, Attila's banner bore the symbol of the Turul.[15] Turkic and Ugrian tribes believed in an eagle-god creator of the universe, though there is no evidence that also the Huns shared this belief.[14]

It is possible that the Turul/ bird of prey was a religious motif in Hunnic art. However, Maenchen-Helfen excluded it could be a representation of their highest god, since, among the Hunnic items on which it appears, there are horse bits, and according to Helfen it is unlikely that the image of the chief deity should be placed on such modest objects.[15] On the other hand, the horse appears to have had a pivotal role in Hunnic life. Maenchen-Helfen also remarked that the use of beak heads was popular among Scythians long before the Huns, and that several cultures from China to the Balkans exhibited a tendency to turn corners of certain items, such as antlers, into beak heads.[14]

Maenchen-Helfen considered the fact that the beak heads and masks are the only pictorial motifs in the Attilid period merely a sign of the impoverishment of Hunnic art in such period.[14]

Gallery

Hunnish set of horse trappings, 4th century

Hunnish set of horse trappings, 4th century Hunnish bracelet, 5th century

Hunnish bracelet, 5th century Silver fibulae from the Hunnish period

Silver fibulae from the Hunnish period Hunnish oval openwork fibula, 4th century

Hunnish oval openwork fibula, 4th century Pair of Hunnish bracelets, early 5th century

Pair of Hunnish bracelets, early 5th century Hunnish saddle fitting of a Gepid prince

Hunnish saddle fitting of a Gepid prince Hunnish horse head fibula

Hunnish horse head fibula Hunnish shoe buckle

Hunnish shoe buckle Diadem

Diadem Hunnish Cauldron found on the fringes of the Tisza floodplain

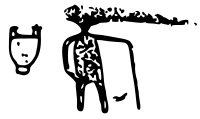

Hunnish Cauldron found on the fringes of the Tisza floodplain Detail of possibly Hunnic or Xiongnu period petroglyph depicting rituals with cauldron, found on a rock on Mount Kyzil Kaja, Minusinsk area, west of the Yenisei, near the Ujbat river, in the former Xiongnu territory

Detail of possibly Hunnic or Xiongnu period petroglyph depicting rituals with cauldron, found on a rock on Mount Kyzil Kaja, Minusinsk area, west of the Yenisei, near the Ujbat river, in the former Xiongnu territory Masks found in Intercisa, on the Danube, dating from the 5th century AD

Masks found in Intercisa, on the Danube, dating from the 5th century AD

References

- Dahm, Murray; Rava, Giuseppe (2022). Hunnic Warrior Vs Late Roman Cavalryman Attila's Wars, AD 440–53. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472852038. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- Illyés, Elemér (1988). Ethnic continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian area. East European Monographs. p. 148. ISBN 9780880331463. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- "The Gepids during and after the Hun Period". www.mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154, 271. ISBN 9781107067226.

- Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781107067226. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780190277536. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Hughes, Ian (2019). Attila the Hun Arch-Enemy of Rome. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781473890329. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Maas, Michael (2015). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9781107021754. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Masek, Zsofia (2017). "A Fresh Look at Hunnic Cauldrons in the Light of a New Found from Hungary" (Document). Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Mei, Jianjun (13 March 2002). "The Metal Cauldrons Recovered in Xinjiang, Northwest China". Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "I calderoni degli Unni (The Huns' cauldrons)". www.samorini.it (in Italian). 11 December 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (2022). The World of the Huns Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. p. 333. ISBN 9780520357204. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- Eurasian Studies Yearbook Volume 67. Eurolingua. 1995. pp. 21, 52.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (2022). Knight, Max (ed.). The World of the Huns Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780520357204. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- Arnold, Dana (2018). Arnold, Dana; Facos, Michelle (eds.). A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art. Wiley. p. 382. ISBN 9781118856338. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)