Hugh Capet

Hugh Capet[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (/ˈkæpeɪ/; French: Hugues Capet [yɡ kapɛ]; c. 939 – 14 October 996)[5] was the King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He is the founder of and first king from the House of Capet. The son of the powerful duke Hugh the Great and his wife Hedwige of Saxony, he was elected as the successor of the last Carolingian king, Louis V. Hugh was descended from Charlemagne's son Pepin of Italy through his mother and paternal grandmother, respectively, and was also a nephew of Otto the Great.[6]

| Hugh Capet | |

|---|---|

Hugh Capet in the 13th century Chronica sancti Pantaleonis | |

| King of the Franks | |

| Reign | 1 June 987 – 14 October 996 |

| Coronation | 1 June 987, Noyon 3 July 987, Paris |

| Predecessor | Louis V |

| Successor | Robert II |

| Born | 939 Paris, West Francia |

| Died | 14 October 996 (aged 56–57) Paris, France |

| Burial | Saint Denis Basilica, Saint-Denis, France |

| Spouse | Adelaide of Aquitaine (m. 969) |

| Issue | Hedwig, Countess of Mons Gisèle, Countess of Ponthieu Robert II, King of the Franks |

| House | Robertian dynasty Capet (founder) |

| Father | Hugh the Great |

| Mother | Hedwige Liudolfing |

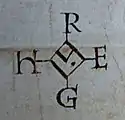

| Signature |  |

The dynasty he founded ruled France for nearly nine centuries: from 987 to 1328 in the senior line, and until 1848 via cadet branches (with an interruption from 1792 to 1814).[7]

Descent and inheritance

The son of Hugh the Great, Duke of the Franks, and Hedwige of Saxony, daughter of the German king Henry the Fowler, Hugh was born sometime between 938 and 941.[8][9][10] He was born into a well-connected and powerful family with many ties to the royal houses of France and Germany.[lower-alpha 3]

Through his mother, Hugh was the nephew of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor; Henry I, Duke of Bavaria; Bruno the Great, Archbishop of Cologne; and finally, Gerberga of Saxony, Queen of France. Gerberga was the wife of Louis IV, King of France and mother of Lothair of France and Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine.

His paternal family, the Robertians, were powerful landowners in the Île-de-France.[11] His grandfather had been King Robert I.[11] King Odo was his granduncle and Emma of France, the wife of King Rudolph, was his aunt.[12] Hugh's paternal grandmother Beatrice of Vermandois was a patrilineal descendant of Charlemagne.[10][13]

Rise of the Robertians

After the end of the ninth century, the descendants of Robert the Strong became indispensable in carrying out royal policies. As Carolingian power failed, the great nobles of West Francia began to assert that the monarchy was elective, not hereditary, and twice chose Robertians (Odo I (888–898) and Robert I (922–923)) as kings, instead of Carolingians.

Robert I, Hugh the Great's father, was succeeded as King of the Franks by his son-in-law, Rudolph of Burgundy. When Rudolph died in 936, Hugh the Great had to decide whether he ought to claim the throne for himself. To claim the throne would require him to risk an election, which he would have to contest with the powerful Herbert II, Count of Vermandois, father of Hugh, Archbishop of Reims, and allied to Henry the Fowler, King of Germany; and with Hugh the Black, Duke of Burgundy, brother of the late king. To block his rivals,[14] Hugh the Great brought Louis d'Outremer, the dispossessed son of Charles the Simple, from his exile at the court of Athelstan of England to become king as Louis IV.[15]

This maneuver allowed Hugh to become the most powerful person in France in the first half of the tenth century. Once in power, Louis IV granted him the title of dux Francorum ("Duke of the Franks"). Louis also (perhaps under pressure) officially declared Hugh "the second after us in all our kingdoms". Hugh also gained power when Herbert II of Vermandois died in 943, because Herbert's powerful principality was then divided among his four sons.

Hugh the Great came to dominate a wide swath of central France, from Orléans and Senlis to Auxerre and Sens, while the king was rather confined to the area northeast of Paris (Compiègne, Laon, Soissons).

French monarchy in the 10th century

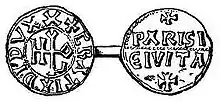

The realm in which Hugh grew up, and of which he would one day be king, bore little resemblance to modern France. Hugh's predecessors did not call themselves kings of France, and that title was not used by his successors until the time of his descendant Philip II. Kings ruled as rex Francorum ("King of the Franks"), the title remaining in use until 1190 (but note the use of FRANCORUM REX by Louis XII in 1499, by Francis I in 1515, and by Henry II about 1550,[16] and on French coins up to the eighteenth century.) The lands they ruled comprised only a small part of the former Carolingian Empire. The eastern Frankish lands, the Holy Roman Empire, were ruled by the Ottonian dynasty, represented by Hugh's first cousin Otto II and then by Otto's son, Otto III. The lands south of the river Loire had largely ceased to be part of the West Francia kingdom in the years after Charles the Simple was deposed in 922. Both the Duchy of Normandy and the Duchy of Burgundy were largely independent, and Brittany entirely so—although from 956 Burgundy was ruled by Hugh's brothers Otto and Henry.[17]

France under Ottonian influence

In 956, when his father Hugh the Great died, Hugh, the eldest son, was then about fifteen years old and had two younger brothers. Otto I, King of Germany, intended to bring western Francia under his control, which was possible since he was the maternal uncle of Hugh Capet and Lothair of France, the new king of the Franks, who succeeded Louis IV in 954, at the age of 13.

In 954, Otto I appointed his brother Bruno, Archbishop of Cologne and Duke of Lorraine, as guardian of Lothair and regent of the kingdom of France. In 956, Otto gave him the same role over Hugh and the Robertian principality. With these young princes under his control, Otto aimed to maintain the balance between Robertians, Carolingians, and Ottonians. In 960, Lothair agreed to grant to Hugh the legacy of his father, the margraviate of Neustria and the title of Duke of the Franks. But in return, Hugh had to accept the new independence gained by the counts of Neustria during Hugh's minority. Hugh's brother, Otto received only the duchy of Burgundy (by marriage). Andrew W. Lewis has sought to show that Hugh the Great had prepared a succession policy to ensure his eldest son much of his legacy, as did all the great families of that time.

The West was dominated by Otto I, who had defeated the Magyars in 955, and in 962 assumed the restored imperial title. The new emperor increased his power over Western Francia with special attention to certain bishoprics on his border; although elected by Lothair, Adalberon, Archbishop of Reims, had imperial sympathies. Disappointed, King Lothair relied on other dioceses (Langres, Chalons, Noyon) and on Arnulf I, Count of Flanders.

Hugh, Duke of the Franks

In 956, Hugh inherited his father's estates, in theory making him one of the most powerful nobles in the much-reduced kingdom of West Francia.[18] As he was not yet an adult, his mother acted as his guardian,[19] and young Hugh's neighbours took advantage. Theobald I of Blois, a former vassal of Hugh's father, took the counties of Chartres and Châteaudun. Farther south, on the border of the kingdom, Fulk II of Anjou, another former client of Hugh the Great, carved out a principality at Hugh's expense and that of the Bretons.[20]

The royal diplomas of the 960s show that the nobles were faithful not only to the Duke of the Franks, as in the days of Hugh the Great, but also to King Lothair. Indeed, some in the royal armies fought against the Duchy of Normandy on behalf of Lothair. Finally, even Hugh's position as second man in the kingdom seemed to slip. Two charters of the Montier-en-Der Abbey (968 and 980) refer to Herbert III, Count of Vermandois, while Count of Chateau-Thierry, Vitry and lay abbot of Saint-Médard of Soissons, bearing the title of "Count of the Franks" and even "count of the palace" in a charter of Lothair.

For his part, Lothair also lost power with the ascendance of the Ottonian monarchy. It waned by participating in the gathering of relatives and vassals of Otto I in 965. However, from the death of the emperor in 973, Lothair wanted to revive the policy of his grandfather to recover Lorraine. Otto's son and successor, Otto II, appointed his cousin, Charles, brother of Lothair, as Duke of Lower Lorraine. This infuriated both Lothair and Hugh, whose sister, Beatrice was the regent for the young Duke Theodoric I of Upper Lorraine. In 978, Hugh thus supported Lothair in opening a war against Otto.

In August 978, accompanied by the nobles of the kingdom, Lothair surprised and plundered Aachen, residence of Otto II, forcing the imperial family to flee. After occupying Aachen for five days, Lothair returned to France after symbolically disgracing the city. In September 978, Otto II retaliated against Lothair by invading France with the aid of Charles. He met with little resistance on French territory, devastating the land around Rheims, Soissons, and Laon. Otto II then had Charles crowned as King of France by Theodoric I, Bishop of Metz. Lothair then fled to the French capital of Paris where he was besieged by Otto II and Charles. Sickness among his troops brought on by winter, and a French relief army under Hugh Capet, forced Otto II and Charles to lift the siege on 30 November and return to Germany. On the journey back to Germany, Otto's rearguard, unable to cross the Aisne in flood at Soissons, was completely wiped out, "and more died by that wave than by the sword." This victory allowed Hugh Capet to regain his position as the first noble of the Frankish kingdom.

Hugh aids Archbishop of Reims

Until the end of the tenth century, Reims was the most important of the archiepiscopal seats of France. Situated in Carolingian lands, the archbishop claimed the primacy of Gaul and the privilege to crown kings and direct their chancery. Therefore, the Archbishop of Reims traditionally had supported the ruling family and had long been central to the royal policy. But the episcopal city was headed by Adalberon of Rheims, nephew of Adalberon of Metz (a faithful prelate to the Carolingians), elected by the King Lothair in 969, but who had family ties to the Ottonians. The Archbishop was assisted by one of the most advanced minds of his time, the schoolmaster and future Pope Sylvester II Gerbert of Aurillac. Adalberon and Gerbert worked for the restoration of a single dominant empire in Europe. King Lothair, 13 years old, was under the tutelage of his uncle Otto I. But upon reaching his majority, he became independent, which defeated their plans to bring the whole of Europe under a single crown. Therefore, they turned their support from Lothair to Hugh Capet.

Indeed, for the Ottonian to make France a vassal state of the empire, it was imperative that the Frankish king was not of the Carolingian dynasty, and not powerful enough to break the Ottonian tutelage. Hugh Capet was for them the ideal candidate, especially since he actively supported monastic reform in the abbeys while other contenders continued to distribute church revenues to their own partisans. Such conduct could only appeal to Reims, who was very close to the Cluniac movement.

Lothair succeeded by short-lived Louis V

With the support of Adalberon of Reims, Hugh became the new leader of the kingdom. In a letter Gerbert of Aurillac wrote to Archbishop Adalberon that "Lothair is king of France in name alone; Hugh is, however, not in name but in effect and deed." (citation needed)

In 979, Lothair sought to ensure his succession by associating his eldest son with the throne. Hugh Capet supported him and summoned the great nobles of the kingdom. The ceremony took place at Compiègne, in the presence of the king, of Arnulf (an illegitimate son of the king), and of Archbishop Adalberon, under Hugh's blessing. The congregation acclaimed Louis V, following the Carolingian custom, and the archbishop anointed the new king of the Franks.

The following year, Lothair, seeing the growing power of Hugh, decided to reconcile with the Emperor Otto II by agreeing to renounce Lorraine. But Hugh did not want the king and the emperor reconciled, so he quickly took the fortress of Montreuil, and then went to Rome. There he met the emperor and the pope, with his confidants Burchard I of Vendôme and Arnulf of Orléans. Tension mounted between Lothair and Hugh. The king married his 15-year-old son Louis to Adelaide of Anjou, who was then more than 40 years old. She brought with her Auvergne and the county of Toulouse, enough to pincer the Robertian territories from the south. However, the marriage failed and the couple separated two years later.

At the death of Otto II in 983, Lothair took advantage of the minority of Otto III and, after making an alliance with the Duke of Bavaria, decided to attack Lorraine. Hugh was careful not to join this expedition.

When the king took Verdun and imprisoned Godfrey (brother of the Archbishop of Reims), Adalberon and Gerbert sought the aid of the duke of the Franks. But Lothair's enterprises came to naught when he died in March 986.

Louis V, following Louis IV and Lothair, declared that he would take the counsels of the duke of the Franks for his policies. It seems the new king wished to launch an offensive against Reims and Laon because of their rapprochement with the empire. Sources are vague on Hugh's role at this time, but it would be his interest to limit the king's excessive pretensions. Louis summoned the archbishop of Reims at his palace at Compiègne to answer for his actions. But while hunting in the forest of Senlis, Louis was killed in a riding accident on 21 or 22 May 987.

Hugh elected King of Franks

In May 987, chroniclers, including Richerus and Gerbert of Aurillac, wrote that in Senlis "died the race of Charles". However, even if Louis died childless, there remained a Carolingian who could ascend the throne: Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, brother of Lothair, uncle of Louis V, first cousin of Hugh Capet through their mothers.

This was nothing extraordinary; it was not the first time that a Robertian would be competing with a Carolingian. In the time of Hugh the Great, the Robertians found it expedient to support the claim of a Carolingian. By 987, however, times had changed. For ten years, Hugh Capet had been openly competing against his king, and appeared to have subjected the great vassals. And his opponent Charles of Lorraine was accused of all evils: he wanted to usurp the crown (978), had allied himself with the emperor against his brother, and had defamed Queen Emma of Italy, his brother's wife. The archbishop of Reims convened the greatest lords of France at Senlis and denounced Charles of Lorraine for not maintaining his dignity, having made himself a vassal of the Emperor Otto II and marrying a woman from a lower class of nobility. Then he promoted the candidacy of Hugh Capet:

Crown the Duke. He is most illustrious by his exploits, his nobility, his forces. The throne is not acquired by hereditary right; no one should be raised to it unless distinguished not only for nobility of birth, but for the goodness of his soul.[21]

Hugh was crowned rex Francorum on 1 June, in Noyon, and again on 3 July 987, in Paris.[22] Immediately after his coronation, Hugh began to push for the coronation of his son Robert. The archbishop, wary of establishing hereditary kingship in the Capetian line, answered that two kings could not be created in the same year. Hugh claimed, however, that he was planning an expedition against the Moorish armies harassing Borrel II, Count of Barcelona (a vassal of the French crown), and that the stability of the country necessitated two kings should he die while on expedition.[23] Ralph Glaber, however, attributes Hugh's request to his old age and inability to control the nobility.[24] Modern scholarship has largely imputed to Hugh the motive of establishing a dynasty against the pretension of electoral power on the part of the aristocracy, but this is not the typical view of contemporaries and even some modern scholars have been less skeptical of Hugh's "plan" to campaign in Spain.[24] Robert was eventually crowned on 25 December that same year.

Election contested by Charles of Lorraine

Charles of Lorraine, the Carolingian heir, contested the succession. He drew support from the Count of Vermandois, a cadet of the Carolingian dynasty; and from the Count of Flanders, loyal to the Carolingian cause. Charles took Laon, the seat of Carolingian royalty. Hugh Capet and his son Robert besieged the city twice, but were compelled to withdraw each time. Hugh decided to make an alliance with Theophano (regent for her son Otto III), but she never replied.

When Adalberon, Archbishop of Reims, died, the archbishopric was contested by his right-hand man, Gerbert of Aurillac, and Arnulf, illegitimate son of King Lothair of France (and nephew of Charles of Lorraine). Choosing Arnulf to replace Adalberon seemed a great gamble, but Hugh made it anyway, and chose him as archbishop instead of Gerbert, in order to appease Carolingian sympathizers and the local populace. Following the customs of those times, he was made to invoke a curse upon himself if he should break his oath of fidelity to Hugh. Arnulf was duly installed, and was confirmed by the pope.

Yet to Arnulf the ties of blood with his uncle Charles was the stronger than the oath he had given Hugh. Gathering the nobles in his castle, Arnulf sent one of his agents and opened the gates of the city to Charles. Arnulf acted as if terrified, and took the nobles with him to a tower, which he had emptied out of supplies beforehand. Thus was the city of Reims compelled to surrender; to keep up appearances, Arnulf and Charles denounced each other, until Arnulf swore fealty to Charles.

Great was the predicament of Hugh, and he began doubting whether he could win the contest by force. Adalberon, bishop of Laon, whom Charles expelled when he took the city, had sought the protection of Hugh Capet. The bishop made overtures to Arnulf and Charles, to mediate a peace between them and Hugh Capet. Adalberon was received by Charles favorably, but was made to swear oaths that would bring curses upon himself if broken. Adalberon swore to them all, "I will observe my oaths, and if not, may I die the death of Judas." That night the bishop seized Charles and Arnulf in their sleep, and delivered them to Hugh. Charles was imprisoned in Orléans until his death. His sons, born in prison, were released.

Dispute with the papacy

After the loss of Reims by the betrayal of Arnulf, Hugh demanded his deposition by Pope John XV. But the pope was then embroiled in a conflict with the Roman aristocracy. After the capture of Charles and Arnulf, Hugh resorted to a domestic tribunal, and convoked a synod at Reims in June 991. There, Gerbert testified against Arnulf, which led to the archbishop's deposition and Gerbert being chosen as replacement.

Pope John XV rejected this procedure and wished to convene a new council in Aachen, but the French bishops refused and confirmed their decision in Chelles (winter 993–994). The pope then called them to Rome, but they protested that the unsettled conditions en route and in Rome made that impossible. The Pope then sent a legate with instructions to call a council of French and German bishops at Mousson, where only the German bishops appeared, the French being stopped on the way by Hugh and Robert.

Gerbert, supported by other bishops, advocates for the independence of the churches vis-à-vis Rome (which is controlled by the German emperors). Through the exertions of the legate, the deposition of Arnulf was finally pronounced illegal. To avoid excommunication of the bishops who sat in the council of St. Basle, and thus a schism, Gerbert decided to let go. He abandoned the archdiocese and went to Italy. After Hugh's death, Arnulf was released from his imprisonment and soon restored to all his dignities. Under the auspices of the emperor, Gerbert eventually succeeded to the papacy as Pope Sylvester II, the first French pope.

Extent of power

Hugh Capet possessed minor properties near Chartres and Angers. Between Paris and Orléans he possessed towns and estates amounting to approximately 400 square miles (1,000 km2). His authority ended there, and if he dared travel outside his small area, he risked being captured and held for ransom, though his life would be largely safe. Indeed, there was a plot in 993, masterminded by Adalberon, Bishop of Laon and Odo I of Blois, to deliver Hugh Capet into the custody of Otto III. The plot failed, but the fact that no one was punished illustrates how tenuous was his hold on power. Beyond his power base, in the rest of France, there were still as many codes of law as there were fiefdoms. The "country" operated with 150 different forms of currency and at least a dozen languages. Uniting all this into one cohesive unit was a formidable task and a constant struggle between those who wore the crown of France and its feudal lords. Therefore, Hugh Capet's reign was marked by numerous power struggles with the vassals on the borders of the Seine and the Loire.

While Hugh Capet's military power was limited and he had to seek military aid from Richard I of Normandy, his unanimous election as king gave him great moral authority and influence. Adémar de Chabannes records, probably apocryphally, that during an argument with the Count of Auvergne, Hugh demanded of him: "Who made you count?" The count riposted: "Who made you king?".[25]

Legacy

Hugh Capet died on 14 October 996 in Paris,[5] and was interred in the Saint Denis Basilica. His son Robert continued to reign.

Most historians regard the beginnings of modern France as having initiated with the coronation of Hugh Capet. This is because, as Count of Paris, he made the city his power centre. The monarch began a long process of exerting control of the rest of the country from there.

He is regarded as the founder of the Capetian dynasty. The direct Capetians, or the House of Capet, ruled France from 987 to 1328; thereafter, the Kingdom was ruled by cadet branches of the dynasty. All French kings through Louis Philippe, and all royals since then, have belonged to the dynasty. Furthermore, cadet branches of the House continue to reign in Spain and Luxembourg.

All monarchs of the Kingdom of France from Hugh Capet to Philip II of France were titled 'King of the Franks'. Documents during Philip II's reign began using the title 'King of France' as dawn of the intimate unification of medieval French population even though Latin was the main language.

Marriage and issue

Hugh Capet married Adelaide,[26] daughter of William Towhead, Count of Poitou. Their children are as follows:

- Gisela, or Gisele, who married Hugh I, Count of Ponthieu[lower-alpha 4][26]

- Hedwig, or Hathui, who married Reginar IV, Count of Hainaut[26]

- Robert II,[26] who became king after the death of his father

A number of other daughters are less reliably attested.[27]

Prophecy

According to tradition, sometime in 981, Hugh Capet recovered the relics of St. Valery, which had been stolen by the Flemings, and restored them to their proper resting place. The saint appeared to the duke in a dream, and said: "For what you have done, you and your descendants shall be kings unto the seventh generation". When he became king, Hugh refused to wear the insignia of royalty, hoping that it would extend his descendants' reign by one generation.

By the literal interpretation, Capetian kingship would thus have ended with Philip Augustus, the seventh king of his line. Figuratively, seven meant completeness, and would mean that the Capetians would be kings for ever. In fact, Capetian kingship lasted until 1848 in France, although the current King of Spain and the Grand Duke of Luxembourg are Capetians.

Reception

Italian poet Dante Alighieri features Hugh Capet as a character in Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. The pilgrim meets Capet on the fifth terrace of Mount Purgatory among souls performing penitence for avarice (Purgatorio 20). In this portrayal, Capet acknowledges himself as the "root of the obnoxious plant / that shadows all the Christian lands" (Purg. 20.43-44). The metaphor of the root of the plant is reminiscent of a family tree.[28] Dante thus condemns Hugh as a main source of the evil that has pervaded and corrupted the French monarchy. Dante's personal resentment towards Hugh's legacy likely stemmed from the fact that his exile had been caused by interference in Florentine politics by the French crown and Pope Boniface VIII in the early fourteenth century.[29] In this way, the "obnoxious plant" of the Capetians casts a shadow over both the papacy and the chance for an emperor that might bring order to Italy, Dante's "two suns."[30]

The myth of Capet's humble origins is another crucial component of Dante's representation of this historical figure in Purgatorio.[30] Though the notion that Capet was the son of a butcher is rightfully reported by critics to be untrue—he was the son of a duke—situating Capet in a lower social position is vital for Dante. This framing draws the Frankish king closer to Dante's own experience as a member of the lower aristocracy, and makes Capet's rise to power feel more extreme.[31] In penance for grasping so high above himself in life, Capet and the other avaricious souls of this terrace must lie face down into the rock. The souls inch slowly up the mountain where they lay, acting in moderation in purgatory, when on earth they moved through life guided by greed.[32]

Notes

- Capet is a byname of uncertain meaning distinguishing him from his father Hugh the Great. Folk etymology connects it with "cape".[1] According to Pinoteau, the name "Capet" was first attributed to the dynasty by Ralph de Diceto writing in London in 1200, maybe because of the position of the early kings as lay abbots of St Martin of Tours, where part of the "cappa" of the saint was allegedly conserved. Other suggested etymologies derive it from terms for chief, mocker or big head. His father's byname is presumed to have been retrospective, meaning Hugh the Elder, this Hugh being Hugh the Younger, Capet being a 12th-century addition.[2]

- Although called Hugo Magnus in at least one contemporary source, a charter of 995 (documented in Jonathan Jarrett,[3] the epithet "Hugh the Great" is generally reserved for his father the Duke of France (898–956).[4]

- For a fuller explanation of the descent and relationships of Hugh, see the genealogical tables in Riché 1993, pp. 367–375.

- Le Jan indicates Gisela married a Hugues avoue de St-Riquier.[26]

References

- Cole, Robert (2005). A Traveller's History of France (7th ed.). New York: Interlink Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-1566566063.

- James, The Origins of France, p. 183.

- "Sales, Swindles and Sanctions: Bishop Sal·la of Urgell and the Counts of Catalonia", International Medieval Congress, Leeds, 11 July 2005, published in the Appendix, Pathways of Power in late-Carolingian Catalonia, PhD dissertation, Birkbeck College (2006), page 295),

- Grimshaw, William (1828). History of France: From the Foundation of the Monarchy, by Clovis, to the final abdication of Napoleon. Philadelphia: John Grigg. p. 38. OCLC 4277602.

- "Hugh Capet | king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Hedwig". Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia.

- "Capetian dynasty | French history | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2022.; "Major Rulers of France | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Critical companion to Dante: "Hugh Capet (ca. 938–996). Hugh Capet was king of France and founder of the Capetian line of kings"; The Rise of the Medieval World, 500–1300: A Biographical Dictionary: "Hugh Capet (939–996). Hugh Capet was founder of the Capetian Dynasty"

- Medieval France: An Encyclopedia: "(ca. 940–996). The son of Hugues Le Grand, duke of Francia, Hugh Capet is traditionally considered the founder of the third dynasty of French Kings, the Capetians"

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band II (Marburg, Germany: J. A. Stargardt, 1984), Tafeln 10, 11

- Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France, 987–1328. London: Hambledon Continuum. p. 69.

- Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians; A Family Who Forged Europe. Translated by Allen, Michael Idomir. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 371.

- Riché 1993, pp. 371, 375.

- James, pp 183–184; Theis, pp 65–66.

- Fanning, Steven; Bachrach, Bernard S. (eds & trans.) The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916–966 (New York; Ontario, Can: University of Toronto Press, 2011), p. 28

- Potter, David (2008). Renaissance France at War: Armies, Culture and Society, C.1480–1560. Warfare in History Series. Vol. 28. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. viii. ISBN 978-1843834052. OL 23187209M.

[...] Louis XII, 1499 [...] LVDOVIVS XII FRANCORUM REX MEDILANI DUX [...] Francis I, 1515 [...] FRANCISCUS REX FRANCORUM PRIMUS DOMINATOR ELVETIORUM [...] Henri II, 1550? [...] HENRICVS II FRANCORVM REX

- James, pp. iii, 182–183; Gauvard, pp. 163–168; Riché 1993, pp. 285 ff

- Riché 1993, p. 264.

- Jules Michelet, History of France, Vol. I, trans. G. H. Smith (New York: D. Appleton, 1882), p. 146

- Theis, pp. 69–70.

- Harriet Harvey Wood, The Battle of Hastings: The Fall of Anglo-Saxon England, Atlantic, 2008, p. 46

- Havet, Julien (1891). "Les couronnements des rois Hugues et Robert". Revue historique. 45: 290–297. JSTOR 40939391.

- Lewis, 908.

- Lewis, 914.

- (in French) Richard Landes, "L'accession des Capétiens: une reconsidération selon les sources aquitaines", in Religion et culture autour de l'an Mil. Royaume capétien et Lotharingie: actes du Colloque Hugues Capet, 987–1987, la France de l'an mil, Auxerre, 26 et 27 juin 1987; Metz, 11 et 12 septembre 1987, Paris: Picard, 1990, ISBN 2708403923, pp. 153–154.

- Le Jan 2003, Tableau no 62.

- Thus Gauvard, p. 531.

- "Purgatorio 20 – Digital Dante". digitaldante.columbia.edu. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- Alighieri, Dante (2003). Purgatorio. Translated by Hollander, Jean; Hollander, Robert. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0385508315.

- "Canto XX. Hugh Capet and the Avarice of Kings". Lectura Dantis, Purgatorio. 2019. pp. 210–221. doi:10.1525/9780520940529-020. ISBN 978-0520940529. S2CID 241582950.

- Moleta, 216.

- Moleta, 211.

Sources

- Gauvard, Claude. La France au Moyen Âge du Ve au XVe siècle. Paris: PUF, 1996. ISBN 2130542050

- Le Jan, Régine (2003). Famille et pouvoir dans le monde franc (VIIe–Xe siècle), Essai d'anthropologie sociale (in French). Éditions de la Sorbonne.

- James, Edward. The Origins of France: From Clovis to the Capetians 500–1000. London: Macmillan, 1982. ISBN 0312588623

- Riché, Pierre. The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Michael Idomir Allen (Translator). Paris: Hachette, 1983. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993 1st ed.), ISBN 978-0812213423

- Theis, Laurent. Histoire du Moyen Âge français: Chronologie commentée 486–1453. Paris: Perrin, 1992. ISBN 2870275870

- Lewis, Anthony W. "Anticipatory Association of the Heir in Early Capetian France." The American Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 4. (Oct., 1978), pp 906–927.