Hugo Sperrle

Wilhelm Hugo Sperrle (7 February 1885 – 2 April 1953), also known as Hugo Sperrle, was a German military aviator in World War I and a Generalfeldmarschall in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Hugo Sperrle | |

|---|---|

Hugo Sperrle in 1940 | |

| Born | 7 February 1885 Ludwigsburg, German Empire |

| Died | 2 April 1953 (aged 68) Munich, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1903–1944 |

| Rank | Generalfeldmarschall |

| Unit | Condor Legion |

| Commands held | 1 Fliegerdivision Luftflotte 3 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross Spanish Cross |

Sperrle joined the Imperial German Army in 1903. He served in the artillery upon the outbreak of World War I. In 1914 he joined the Luftstreitkräfte as an observer then trained as a pilot. Sperrle ended the war at the rank of Hauptmann (Captain) in command of an aerial reconnaissance attachment of a field army.

In the inter-war period Sperrle was appointed to the General Staff in the Reichswehr, serving the Weimar Republic in the aerial warfare branch. In 1934 after the Nazi Party seized power, Sperrle was promoted to Generalmajor (Brigadier General) and transferred from the army to the Luftwaffe. Sperrle was given command of the Condor Legion in November 1936 and fought with the expeditionary force in the Spanish Civil War until October 1937.

Sperrle was appointed as commanding officer of Luftwaffengruppenkommando 3 (Air Force Group Command 3) the forerunner of Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet 3) in February 1938. Sperrle was used during the Anschluss and Czech crisis by the Nazi leadership to threaten other governments with bombardment. Sperrle attended several important meetings with Austrian and Czech leaders for this purpose upon the invitation of Adolf Hitler.

In September 1939 World War II began with the invasion of Poland. Sperrle and his air fleet served exclusively on the Western Front. He played a crucial role in the Battle of France and Battle of Britain in 1940. In 1941 Sperrle directed operations during The Blitz over Britain. From mid-1941 his air fleet became the sole command in the west. Through 1941 and 1942 he defended German-occupied Europe against the Royal Air Force, as well as the United States Army Air Forces from 1943. Sperrle's command was depleted in the battles of attrition forced on him by the Combined Bomber Offensive.

By mid-1944, Sperrle's air fleet had been reduced to impotence and it could not repel the Allied landings in Western Europe. As a consequence, Sperrle was dismissed to the Führerreserve and never held a senior command again. On 1 May 1945 he was captured by the British. After the war, he was charged with war crimes at the High Command Trial but was acquitted. Sperrle was involved in the bribery of senior Wehrmacht officers.

Early life and World War I

Sperrle was born in the town of Ludwigsburg, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, German Empire on 7 February 1885 the son of a brewery proprietor, Johannes Sperrle and his wife Luise Karoline, née Nägele.[Note 1] He joined the Imperial German Army on 5 July 1903 as a Fahnenjunker (officer cadet).[2] Sperrle was assigned to the 8th Württemberg Infantry Regiment ("Großherzog Friedrich von Baden" Nr. 126), a regiment in the Army of Württemberg, and after a year received his commission and promotion to Leutnant on 28 October 1912.[2] Sperrle served another year until his promotion to Oberleutnant (second lieutenant) in October 1913.[3][2]

At the outbreak of World War I, Sperrle was training as an artillery spotter in the Luftstreitkräfte (German Army Air Service). On 28 November 1914 Sperrle was promoted to Hauptmann.[2] Sperrle did not distinguish himself in battle as his fellow staff officers in World War II had done, but he forged a solid record in the aerial reconnaissance field.[3]

Sperrle served first as an observer, then trained as a pilot with the 4th Field Flying Detachment (Feldfliegerabteilung) at the Kriegsakademie (War Academy). Sperrle went on to command the 42nd and 60th Field Flying Detachments, then led the 13th Field Flying Group.[3] After suffering severe injuries in a crash,[4] Sperrle moved to the air observer school at Cologne thereafter and when the war ended he was in command of flying units attached to the 7th Army.[3] For his command he was awarded the House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords.[2]

Inter-war years

Sperrle joined the Freikorps and commanded an aviation detachment. He then joined the Reichswehr.[3] Sperrle commanded units in Silesia including the Freiwilligen Fliegerabteilungen 412 under the leadership of Erhard Milch. Sperrle fought on the East Prussia border during the 1919 conflict with Poland.[5] He assumed command on 9 January 1919.[6]

On 1 December 1919, commander-in-chief of the German army, Hans von Seeckt issued a directive for the creation of 57 committees, encompassing all the military branches, to compile detailed studies of German war experiences. Helmuth Wilberg led the air service sector and Sperrle was one of 83 commanders ordered to assist. The air staff studies were conducted through 1920.[7]

General Staff

Sperrle served on the air staff for Wehrkreis V (Military District 5) in Stuttgart from 1919 to 1923, then the Defence Ministry until 1924.[3] Sperrle then served on the staff of the 4th Infantry Division near Dresden. Sperrle travelled to Lipetsk in the Soviet Union at this time, where the Germans maintained a secret air base and founded the Lipetsk fighter-pilot school. Sperrle purportedly visited the United Kingdom to observe Royal Air Force exercises.[8] At Lipetsk, Hugo Sperrle and Kurt Student acted as senior directors which trained some 240 German pilots between 1924 and 1932.[9]

The air staff remained small, but Sperrle's contingent were present in the 4,000 officers retained in the military. In 1927 Sperrle, at the rank of Major, replaced Wilberg as head of the air staff at the Waffenamt an Truppenamt (Weapons and Troop Office). Sperrle was selected for his expertise in technical matters; he was seen as highly qualified staff officer with combat experience in commanding the flying units of the 7th army during the war.[10] On 1 February 1929[4] Sperrle was replaced with Hellmuth Felmy.[10] Sperrle's departure came as he was pressing for an autonomous aviation authority. Felmy persisted, and on 1 October 1929, the Inspektion der Waffenschulen und der Luftwaffe came into existence under the command of Major General Hilmar von Mittelberger—it was the first use of the term "Luftwaffe". By 1 November 1930, the embryonic air headquarters could count 168 aviation officers including Sperrle.[11]

Sperrle was promoted to Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) in 1931 while commanding the 3rd battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment from 1929 to 1933. Sperrle ended his army career in command of the 8th Infantry Regiment, from 1 October 1933 to 1 April 1934.[8] At the rank of Oberst (colonel), Sperrle was given command of the headquarters of the First Air Division (Fliegerdivision 1). Sperrle was given responsibility for coordinating army support aviation.[12] Sperrle's official title was Kommandeur der Heeresflieger (Commander of Army Flyers).[13] After Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party seized power, Hermann Göring created and Reich Air Ministry. Göring handed most of the squadrons in existence to Sperrle because of his command experiences.[14]

Sperrle was involved in the difficulties in German aircraft procurement. Four months after assuming command, Sperrle was rigorously critical of the Dornier Do 11 and Dornier Do 13 in a conference on 18 July 1934. Five months later, with development failing, Sperrle met with Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, head of aircraft development and Luftkreis IV commander Alfred Keller, a wartime bomber pilot. It was decided Junkers Ju 52 production would be a stopgap, while the Dornier Do 23 reached units in the late summer, 1935. The awaited Junkers Ju 86 was scheduled for testing in November 1934 and the promising Heinkel He 111 in February 1935. Richthofen remarked, "it is better to have second-rate equipment than none at all", though he was responsible for bringing in the next generation of aircraft.[13]

On 1 March 1935, Hermann Göring announced the existence of the Luftwaffe. Sperrle was transferred to the Reich Air Ministry. Sperrle was initially given command of Luftkreis II (Air District II), and then Luftkreis V in Münich upon his promotion to Generalmajor (Brigadier General) on 1 October 1935.[8][15] Sperrle remained in Germany until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. He commanded all German forces in Spain from November 1936 to November 1937.[16]

Condor Legion

Sperrle was the first commander of the Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War. The Legion was a corps of German airmen sent to provide support to General Franco who led the Spanish Fascists, known as the Nationalists, against their enemies, the left-wing Republicans. Sperrle was given command of all German forces earmarked for operations in Spain on his appointment.[16] On 1 November 1936 the Legion totalled 4,500 men and by January 1937 the organisation had grown to 6,000 men.[17] The volunteers were interchanged over the course of the conflict, allowing for the maximum number to gain combat experience.[17]

Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen was assigned to Sperrle as chief of staff, replacing Alexander Holle.[18] Sperrle needed a highly competent man with a staff officer background. Sperrle had the advantage of knowing Richthofen since the 1920s and thought highly of his chief of staff.[19] Sperrle privately viewed Richthofen as a ruthless snob, and Richthofen disliked his superior's coarse wit and table manners. Professionally, they had few disagreements, and Richthofen's good relationship with Franco encouraged Sperrle to leave day-to-day affairs in his hands.[20]

Sperrle and Richthofen made an effective team in Spain. Sperrle was experienced, intelligent with a good reputation. Richthofen was considered a good combat leader. They combined to advise and oppose Franco to prevent the misuse of their air power. Both men were blunt with the Spanish leader and although the Germans and Spanish did not like each other, they developed a healthy respect which translated into an effective working relationship.[21] Richthofen and Sperrle agreed German support should be limited, for Franco's rule would not be perceived as legitimate if he received lavish foreign aid. Their view was reported to Berlin.[22]

Sperrle was assisted by the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL—High Command of the Air Force). Staff officers were trained to solve operational level problems and the OKL's reluctance to micromanage gave Sperrle and Richthofen a free hand to devise solutions to tactical and operational problems. An important step was the development of ground-air communication, via the use of frontline signals posts which were in contact with army and airbases simultaneously. Information telephoned to airbases was relayed rapidly by radio to aircraft in flight. This innovation was put into practice during the conflict.[23]

Sperrle left Germany by air on 31 October 1936 and arrived in Seville, via Rome on 5 November.[24] Sperrle was sent a Kampfgruppe (bomber group—K/88), Jagdgruppe 88 (fighter group 88—J/88) and Aufklärungsstaffel (reconnaissance squadron—AS/88). They were supported by a Flak Abteilung (F/88) with three heavy and two light batteries with communications, transport and maintenance units. The Germans could not afford to fully equip the Legion, and so the air group made use of Spanish equipment. Of the 1,500 vehicles used, there were 100 types creating a maintenance nightmare.[25] The first mission for the Legion was to airlift 20,000 men of the African Army. These veterans, once landed, provided a core of battle–hardened veterans.[22]

Spanish Civil War

Sperrle began the war with 120 aircraft, and for the first four months the German aviators failed to make an impact.[24] Sperrle lost 20 percent of his strength in the failed attempt to seize Madrid in 1936. The material support provided was inadequate and left him with just 26 Ju 52s and two Heinkel He 70 aircraft by the end of January 1937. Sperrle's personal leadership and the dedication of senior officers prevented a collapse in morale. The cause of this defeat was the appearance of Soviet-designed and built Polikarpov I-15 and Polikarpov I-16 fighter aircraft in the Spanish Republican Air Force which won air superiority.[24] Bombing raids against Cartagena and Alicante, and the Soviet air base at Alcalá de Henares, failed.[26] Sperrle personally led an attack against the Republican Navy at Cartagena, sinking two ships. The Republican fleet was forewarned, however, and the majority put to sea and escaped the bombing.[27] Attacks against Madrid, in which 40 tons of bombs were dropped from 19 November 1936, also failed. The bombing and shelling inflicted 1,119 casualties between 14 and 23 November, including 244 dead—303 buildings were hit.[26] The Legion's bomber group temporarily gave up daylight bombing after the failed Fascist offensive.[26]

Sperrle's airmen switched to attacking choke-points around Madrid. Operations were complicated by the Sierra de Guadarrama and Sierra de Gredos mountain range. Pilots suffered from circulation problems in non-pressurised cockpits while flying close to the top of the peaks, but only one aircraft and five men were lost to the natural barriers. Influenza and pneumonia outbreaks due to poor living conditions continued to undermine morale. One of the main problems was the inadequate fighter aircraft. The Heinkel He 51 was not up to the job, Sperrle requested Berlin send modern aircraft. In December three Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters were in Spain, only to return the following February, followed by a single Heinkel He 112 prototype, and Junkers Ju 87 dive-bomber. Richthofen travelled to Berlin to secure more of these types in agreement with chief of staff Albert Kesselring, Ernst Udet, and Milch. Sperrle's command began receiving the Dornier Do 17, He 111, Ju 86 bombers and Bf 109 fighters in January 1937.[28] On 1 April 1937 Sperrle was promoted to Generalleutnant (Major General).[29]

The Nationalists turned to destroying the Republican army enclave along the Bay of Biscay in the summer, 1937. Sperrle moved his headquarters to Vitoria to lead his small force of 62 aircraft. The Biscay Campaign began on 31 March with the Bombing of Durango. Spanish nationalists reported Republican army movements in the town, but before the bombers arrived they withdrew, leaving the bombers to devastate the town and kill 250 civilians. Sperrle protested to the Nationalists about the "waste of resources", but his own authorised attacks on the town's arms-factory were inaccurate and did just as much to damage the Legion's image.[30] Thereafter Sperrle supported the battle for Otxandio. The Nationalists refused to cooperate in an encirclement operation allowing the defenders to retreat toward Guernica. In a farcical moment Sperrle was arrested on a visit to the front by Nationalist forces as a suspected spy.[31]

Sperrle's staff had no file information on Guernica. Richthofen earmarked the town's Rentaria Bridge for attack, but he seems to have been more interested in Guerricaiz six elms (10 km) south east of Guernica. Richthofen referred to this town as "Guernicaiz" in his diary. The Republican left flank had to retreat through Guernica and the air staff earmarked it for bombing. Richthofen's diary entry, dated 26 April 1937, documented the purpose of the attack. His plan was to block the roads to the south and east of Guernica, thereby offering a chance to encircle and destroy Republican forces.[31]

Later that day, 43 bombers dropped 50 tons of bombs on the town.[32] The bombing has been controversial ever since. The attack, described by some as "terror bombing", was not planned as an attack on the populace and there is no evidence the Germans targeted civilian morale. Guernica acted as an important transportation hub for 23 battalions in positions east of Bilbao. Two battalions—the 18th Loyala and Saseta—were in the town.[33] The attack prevented the fortification of the Guernica and closed the roads to traffic for 24 hours, preventing Republican forces from evacuating their heavy equipment across the bridge.[33] While there is no evidence civilians were targeted, 300 Spanish people died, and there is no record of any German air commanders expressing sympathy or concern for civilians in the vicinity of a military target.[34] Sperrle was not reprimanded for Guernica.[29]

The Condor Legion supported the Nationaists in the Battle of Bilbao and played a large role in defeating a Republican offensive in the Battle of Brunete, near Madrid. In attacking airfields, using the flak battalion on the front line, and committing the 20 Bf 109 fighters in the fighter escort role the Nationalists gained air superiority over the 400-strong Republican Air Force. The Nationalists destroyed 160 aircraft for the loss of 23.[35] Sperrle's men routed eight battalions of infantry and large numbers of tanks in the close air support and interdiction role. From this point on, the Legion possessed general air superiority and the flexibility to transfer rapidly to other fronts to support the land war.[36]

Returning north, In August and September 1937 Sperrle's legion assisted Franco's victory at the Battle of Santander with only 68 aircraft—none of the Brunete losses had been replaced.[37] The Republican reportedly lost 70,000 men captured.[29] For the remainder of September the German command focused on the Asturias Offensive which ended the War in the North.[38] Sperrle lost 12 aircraft and 22 men killed, amounting to 17.5 percent of his strength. The attacks, which faced opposition from only 45 Republican aircraft were effective and imposed up to 10 percent losses on some Republican infantry formations. Republican commander Adolfo Prada later stated the bombing had buried entire units in rubble.[37]

In late 1937, Sperrle fought against the interference of Wilhelm Faupel, one of Adolf Hitler's advisors in Spanish affairs. The dispute became so damaging, Hitler removed both men from their positions.[39] Sperrle transferred command of the Condor Legion to Generalmajor Hellmuth Volkmann and returned to Germany on 30 October.[40][41] On 1 November 1937 Sperrle was promoted to General der Flieger.[29]

Anschluss and annexation of Czechoslovakia

Sperrle was given command of Luftwaffe Group 3 (Luftwaffengruppenkommando 3) on the 1 February 1938 which eventually became Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet 3) in February 1939. Sperrle commanded the air fleet for the remainder of his military career.[42]

Sperrle was used by Hitler in his foreign policy to intimidate small neighbours with the Luftwaffe, which had earned a reputation in Spain. On 12 February 1938, Hitler invited Sperrle to a meeting at Berchtesgaden with Kurt Schuschnigg, chancellor of the Federal State of Austria. Generals Wilhelm Keitel, Walther von Reichenau were also in attendance. The meetings eventually helped pave the way for Anschluss, the Nazi seizure of Austria.[43] The first meeting secured Austrian Nazi Dr Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Interior Minister. When Schuschnig announced a plebiscite on Austrian independence, Hitler ordered Sperrle's Luftkreis V to mobilise for an invasion on 10 March. On 12 March Sperrle's airmen dropped leaflets over Vienna. All three of Sperrle's combat units, KG 155, KG 255 and JG 153, moved into airfields around Linz and Vienna during the invasion.[44]

On 1 April 1938, Luftwaffengruppenkommando 3 and its subordinate command, Fliegerkommandeure 5, under Major General Ludwig Wolff, had one Jagdgeschwader (fighter wing), two Kampfgeschwader (bomber wings) and one Sturzkampfgeschwader (Dive-bomber wing).[45] Sperrle's air fleet was used to threaten the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha, into accepting Nazi rule and the formation of Slovakia.[46] Sperrle possessed 650 aircraft in Fliegerdivision 5, which formed part of his command. His orders were to support the 12th Army in the event an invasion of Czechoslovakia was required. Albert Kesselring commanding Luftwaffengruppenkommando 2, was given half of the 2,400 aircraft supporting the invasion and the responsibility of supporting three field armies.[47] The Munich Agreement ended the prospect of war and Sperrle's forces landed at Aš airfield as the Wehrmacht annexed the Sudetenland in October 1938.[48]

In March 1939 Hitler decided to annex Czechoslovakia completely and risk war. He turned once again to the Luftwaffe to assist him achieving diplomatic results. The threat of aerial bombardment proved a crucial in forcing smaller nations to submit to German occupation. The successes confirmed Hitler's view that air power could be used politically, as a "terror weapon".[49] In a series of meetings in Berlin, Hitler told Hácha that half of Prague could be destroyed in two hours, and hundreds of bombers were ready for the operation.[50] Sperrle was asked by Hitler to talk about the Luftwaffe, to intimidate the Czech president.[46] Hácha purportedly fainted, and when he regained consciousness, Göring screamed at him, "think of Prague!"[51]

The elderly President reluctantly ordered the Czechoslovakian Army not to resist. The aerial part of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia was carried out by 500–650 aircraft belonging to Sperrle's newly renamed air fleet, Luftflotte 3.[51] The majority of these aircraft were concentrated in the 4 Fliegerdivision (4th Flying Division). The operational condition of the Luftwaffe was at 57 percent with 60 percent requiring maintenance, while depots had only enough replacement aero engines to cover 4 to 5 percent of frontline strength.[52] Only 1,432 of the 2,577 aircrew available were fully trained. Just 27 percent of bomber crews were instrument trained. These problems effectively reduced fighter and bomber units to 83 and 32.5 percent of their strength. The Luftwaffe's saving grace was that the British, French and Czech air forces were in slightly worse condition in 1939.[53]

World War II

On 1 September 1939, the Wehrmacht invaded Poland prompting the British Empire and France to declare war in her defence. Sperrle's Luftflotte 3 remained guarding German air space in western Germany and did not contribute to the German invasion, made possible by the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. The air fleet's Order of battle had been stripped of almost all of the combat units it held in March 1939. Only two reconnaissance staffel (squadrons) and a single bomber unit attached to Wekusta 51 remained.[54] Sperrle received the competent Major General Maximilian Ritter von Pohl as his chief of staff. The two men made for a "good partnership".[55] Sperrle was also assigned Major General Walter Surén, appointed as the air fleet's chief signals officer. Surén planned and organised the German field communications for the offensive in 1940.[56] While guarding the Western Front during the Phoney War, Sperrle's small fleet of 306 aircraft—which included 33 obsolete Arado Ar 68s—fought off probing attacks of French and British aircraft.[55]

Sperrle developed a reputation as gourmet, whose private transport aircraft featured a refrigerator to keep his wines cool, and although as corpulent as Göring, he was reliable and as ruthless as his superior.[55] Sperrle wanted his air fleet to take a more aggressive stance and won over Göring. On 13 September 1939 he was authorised to undertake long-range high altitude reconnaissance missions at extreme altitudes. Sperrle had already taken the initiative on 4 September when I./KG 53 carried out such an operation.[57] Photographic operations over France authorised by the OKL began on 21 September, which the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht did not sanction until four days later.[57] Sperrle lost eight aircraft over 21–24 November 1939, but succeeded in obtaining good reconnaissance results. The losses prompted his use of fighter escorts on the return journey.[57] Reconnaissance operations were eased when Sperrle received KG 27 and KG 55 once the Polish campaign had ended.[57]

Battle of France

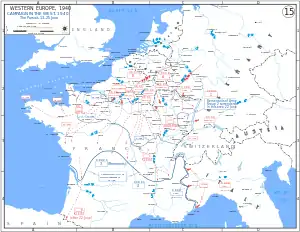

Luftflotte 3 was heavily reinforced in the spring, 1940. Sperrle's headquarters was based at Bad Orb. The air fleet was assigned I. Flakkorps under Generaloberst Hubert Weise, I. Fliegerkorps under Generaloberst Ulrich Grauert at Cologne, the II. Fliegerkorps under Generaloberst Bruno Loerzer at Frankfurt, and V. Fliegerkorps under command of General Robert Ritter von Greim at Gersthofen. Jagdfliegerführer 3 (Fighter Flyer Command 3) under the command of Oberst Gerd von Massow was assigned to the air fleet at Wiesbaden. Massow was replaced during the campaign by Oberst Werner Junck.[58] For the coming battle, Sperrle had 1,788 aircraft (1,272 operational) at his disposal.[59] Opposing Sperrle, was the Armée de l'Air (French Air Force) eastern (ZOAE) and southern (ZOAS) zones under Général de Corps d'armée Aérien René Bouscat and Robert Odic. Bouscat had 509 aircraft (363 operational) and Odic 165 (109 combat ready).[60]

I. Fliegerkorps covered a line running from Eupen, to the Luxembourg border, westward through Fumay, south of Laon to Senlis and the Seine at Vernon through to the English Channel with just 471 aircraft. Cloudy conditions prevented the bomber wings from finding airfields, so industrial targets were attacked instead.[59] II. Fliegerkorps operated from Bitsch to Revigny, to Villenauxe, then west north of Orléans and south of Nantes to the Atlantic Ocean south of the Loire river with only 429 aircraft. V. Fliegerkorps covered south of this line with 498 aircraft and the 359 fighters of Jagdfliegerführer 3.[59]

Fall Gelb began on 10 May 1940. Sperrle's air fleet engaged in operations supporting Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt and Army Group A in the Battle of Belgium and Battle of France, as well as Army Group C.[61][62] Sperrle's counter-air campaign started badly, reflecting poor photographic interpretation of targets, though he later claimed Luftflotte 3's operations were decisive in achieving air superiority.[59] Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 achieved far greater success.[63] Only 29 of the 42 airfields bombed were being used. Three RAF Advanced Air Striking Force bases were struck. Sperrle's men claimed 240 to 490 aircraft destroyed, mostly "in hangars"—Allied losses were actually 40 first-line aircraft.[59] The penalty for failing to neutralise Allied fighter units cost Sperrle 39 aircraft. Loerzer lost 23—the highest loss of any air corps on the day.[64]

Weiss' Flakkorps repulsed the RAF ASSAF attacks against the German advance, inflicting a 56 percent loss rate. From 10 to 13 May 1940 Sperrle's air fleet was credited with 89 aircraft destroyed in dogfights, 22 by flak, and 233 to 248 on the ground. The most successful day recorded was on 11 May; 127 aircraft were claimed—100 on the ground and 27 in the air.[59] In a notable incident, 8./KG 51—one of the air fleet's units, bombed Freiburg in error causing 158 civilian casualties and killing 22 children. To cover up the mistake, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels blamed the British and French for the "Freiburg massacre".[64]

Sperrle's bombers did lay the foundations of a break-through. Loerzer and Grauert's air corps ordered their reconnaissance aircraft to range approximately 400 kilometres into French territory. They avoided the Sedan area so not to attract the attention of the French to German forces advancing on it, they carefully monitored the Allied reactions. Sperrle's air corps commanders targeted air interdiction operations and ordered, attacks on rail communications to prevent the westward deployment of the French Army from the Maginot Line and to pin down Allied reserves by disrupting communications across the Meuse. 26 French rail stations were bombed as were 86 localities from 10 to 12 May. Sperrle maintained the pressure on airfields—44 were struck on the 11–12 May. Loerzer and V. Fliegerkorps, under Greim, also bombed road traffic around Charleville-Mézières.[64]

On 13 May, Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Army was poised to cross the Meuse at Montherme, with Heinz Guderian's XIX Army Corps at Sedan.[65] To support the breakthrough, Generalleutnant Wolfram von Richthofen's VIII. Fliegerkorps was transferred to Luftflotte 3.[66] Loerzer, supplemented by some of Richthofen's forces, supported Guderian's breakthrough at Sedan.[65] Sperrle arranged a single, massive bombing of the defences; Loerzer did not carry out the plan, but a series of bombing operations on the Meuse front. II. Fliegerkorps flew 1,770 missions, Richthofen's command flew 360. The bombing played an important role in allowing the breakthrough at Sedan, while Sperrle's fighters repulsed attempts by the Allies to bomb the bridge on 14 May, following their capture.[67] German air defences accounted for 167 bombers destroyed.[68]

During the breakthrough to the English Channel, rail networks were attacked to prevent Allied forces rallying. Greim's V. Fliegerkorps subjected regrouping French forces to heavy air bombardment. From 13 to 24 May, 174 French rail stations were bombed as were 186 localities, while factories were struck on 35 on occasions and airfields 47 times.[69] Guderian's advance tore through the heart of ZOAN's area and AASF's infrastructure threatening the western airfields of ZOAE. The British abandoned France on 19 May, a day before the German army reached the Channel at Amiens.[69] Sperrle's subordinates, Richthofen and Greim lost 47 reconnaissance aircraft in five days in a bid to find targets.[70]

By this time, Sperrle's boundary with Kesselring ran down the Sambre to Charleroi. Sperrle's job was to protect Guderian's southern flank, though he was ordered to assist against an attempted counter-attack near Arras by supporting the 4th Army advance north.[70] Grauert's I. Fliegerkorps contributed to 300 sorties over Arras.[71] Loerzer and Greim protected Guderian along the Aisne, the former supporting the 2nd and 12th armies. Sperrle's subordinates flew only seven operations against airfields from 20 to 23 May, but 54 against rail stations and another 47 against localities.[72]

Sperrle and Kesselring objected to the halt order during the Battle of Dunkirk. Neither man believed the pocket could be reduced by air power alone.[71] Sperrle, according to Richthofen, was ambivalent and had made few provisions for an attack on the port, preferring to concentrate on his area of operations in the south.[71] Richthofen and Kesselring argued their commands had suffered heavy losses and were in no position to gain air superiority.[73] The campaign began promisingly when Grauert and Loerzer assisted in the bombing and destruction of the inner harbour forcing Allied shipping to use the poorer outer harbour.[74] On 26 May, the chiefs of staff of I., II., V. and VIII. Fliegerkorps met at Château de Roumont, near Ochamps, with Sperrle for a conference on coordination issues. ULTRA at Bletchley Park intercepted Richthofen's signals and ten aircraft were dispatched to bomb the building, which was hit but caused little damage.[75]

Kesselring's air fleet carried the burden of operations over Dunkirk,[73] but Sperrle's men were also attacking shipping. Keller was ordered to destroy Belgian ports in support of the 18th Army, while 30 aircraft from Loerzer's II. Fliegerkorps—including 12 from KG 3—were lost in battle with Air Vice Marshal Keith Park's No. 11 Group RAF. Approximately 320 tons of bombs were dropped, which killed 21 German airmen prisoners of war awaiting transport to England and injured 100 more.[76] From 27 May, Sperrle's I and II air corps attempted to gain air superiority over the Calais–Dunkirk area—Calais had fallen the previous day. Massow's Jafü 3 provided fighter escort.[76] Over the ports, the German air fleets sank or damaged 89 ships (126,518 grt) and eight destroyers with a further 21 damaged. Sperrle and Kesselring failed to prevent the Dunkirk evacuation, despite flying 1,997 fighter, 1,056 bomber and 826 "strike" operations.[77]

Gelb was complete, and the OKL prepared for Case Red. The Luftflotten were reorganised; Sperrle retained II. and V. Fliegerkorps along with I. Flakkorps. The flak corps was reorganised into two brigades, with four regiments each with the firepower of 72 batteries. Sperrle was required to strike far deeper into France, and was given the majority of Zerstörer (destroyer aircraft) equipped with Messerschmitt Bf 110—half of them given to Greim and Loerzer. Sperrle could muster 1,000 aircraft.[78] On 5 June, Sperrle's order of battle lists Richthofen's VIII corps and Massow's Jafü 3.[79] Opposing them was 2,086 aircraft of the Armée de l'Air, but production of aircraft was not matched by component manufacture, and only 29 percent were operational.[80]

In a prelude to the offensive, Sperrle planned to carry out strategic bombing operations against Paris. Sperrle had long-planned for air attacks on Paris using II., V. and VIII. Fliegerkorps in May.[81] He was forced to abandon the plan on 22 May because of weather, but the following day, the OKL prepared a plan for Operation Paula. The plan was to attack the estimated 1,000 French aircraft detected on Parisian airfields, but also to attack factories and destroy the morale of the French people.[81] The operation was undone by poor staff work and excessive confidence in the Enigma machine. ULTRA intercepted a VIII. Fliegerkorps message to KG 77's commanding officer, which named Paris as the target. The ZOAN increased its operational strength to 120 fighters and were alerted an hour before the German bombers got airborne. The operation inflicted minor damage.[82]

On 5 June Sperrle's forces flew eight bombing operations against railways and localities, 21 to 31 against road targets, 12 against troop columns and 34 to 42 against French Army defences or strongpoints. II. Fliegerkorps alone flew 276 bombing missions.[83] On 12 June, as the French front collapsed, Sperrle planned a new assault upon Paris, but it was declared an open city before it could be carried out.[84] Sperrle was ordered to support Rundstedt advancing southward, with orders to encircle the Maginot Line, from the west. Luftflotte 3 carried out bridge interdiction operations in the Loire and on 17 June Guderian reach the border with Switzerland completing the encirclement. The campaign played out for a further five days, which came as Luftwaffe logistics were breaking down—fuel and ammunition shortages were acute and relied on air transportation.[85] Sperrle attempted to prevent the British Operation Aerial—a second evacuation—but the only success was the sinking of Lancastria, with 5,800 lives lost.[86]

On 20 June arrangements were made for the Armistice of 22 June 1940. Upon learning of it, Sperrle ordered the abandonment of a planned bombing operation against Bordeaux. At 21:00 on 24 June Sperrle ordered that Luftflotte 3 cease operations by 00:35 the next morning.[87] In the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony Sperrle was promoted to the said rank.[61]

Battle of Britain

In July 1940 Winston Churchill's government rejected peace overtures from Hitler. Hitler resolved to knock Britain out of the war. The OKL began tentative planning for Operation Eagle Attack to destroy RAF Fighter Command to gain air superiority, before supporting an amphibious landing in Britain, codenamed, Operation Sea Lion.

Sperrle thought the RAF could be defeated en passant. His personal strategy to attack ports and merchant shipping was overruled by Göring, ostensibly because the ports would be required for the invasion.[88] Kesselring's contemporary notes indicate he thought air superiority could only be attained for a short time, since most airfields and factories in Britain were out of range.[89] Sperrle and Kesselring miscalculated, or were misled by intelligence, into underestimating the number of fighter aircraft available to Fighter Command—they put the RAF total at 450 aircraft when the real figure was 750.[90] Chronic intelligence failures on British production, defence systems and aircraft performance inhibited the German air operation throughout the battle.[91][92] Joseph Schmid, the OKL's chief intelligence officer, was primarily responsible for providing inaccurate and distorted information to senior German air commanders encouraging enormous over-confidence.[92]

The Luftwaffe regrouped after the Battle of France into three Luftflotten (Air Fleets) . Luftflotte 2, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, Luftflotte 5, led by Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff was based in Norway and Luftflotte 3, under Generalfeldmarschall Sperrle. Luftflotte 2, whose units were based in northern Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and France north of the Seine, would be concerned mainly with the area east of a line from Le Havre through Selsey Bill to the Midlands; Luftflotte 3, based in western France, would deal similarly with objectives west and north-west of that line. Each Luftflotte was to attack shipping off its own stretch of coast. Diversionary attacks, intended to draw off part of the defences from the south, would be made on north-east England, south-east Scotland and shipping in adjacent waters by Luftflotte 5 from Norwegian and Danish airfields.[93]

Kesselring was responsible for all air force units in northern Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and north-eastern France while Sperrle was in control of forces in northern and western France.[94] Luftflotte 3 was assigned Alfred Keller's Fliegerkorps IV, based in Brittany, Richthofen's Fliegerkorps VIII in the Cherbourg region, and Greim's Fliegerkorps V in the Seine area—precise boundaries between the air corps are not known.[95] The entire bomber strength of Sperrle's air fleet was reserved for night bombing.[96] Sperrle's command did not begin large-scale daylight attacks until the last week of September.[97]

Sperrle's first task against the British Isles was during the Kanalkampf (Channel Battle) phase of what became known as the Battle of Britain. The aim was to draw out Fighter Command into dogfights by attacking Channel Shipping.[98] Targeting British convoy systems, in July 1940 Sperrle's air fleet claimed 90 vessels sunk for approximately 300,000 tons—a third of this was claimed over August and September.[99] The claims were widely optimistic. Only 35 ships were sunk during the Kanalkampf period.[100] Sperrle was becoming disconcerted at the personnel, rather than aircraft, losses. Two days before Operation Eagle—scheduled for 13 August—he had lost two Gruppenkommandeur and a Staffelkapitän. Sperrle knew he could not afford to lose experienced officers at such a rate.[101]

The emphasis of German air attacks switched to bombing Fighter Command bases and its infrastructure. On 13 August 1940, Sperrle's air fleet played a role in the failed Unternehmen Adlerangriff ("Operation Eagle Attack").[102][103] As night fell, Sperrle sent Kampfgruppe 100 (Bombing Group 100) to bomb Supermarine Spitfire factory at Castle Bromwich, Birmingham which failed to achieve anything.[104] Sperrle, Kesselring, Grauert and Loerzer were summoned to Karinhall to explain why the operation has been a mess. At the meeting, it was decided to intensify attacks from all directions, including Air Fleet 5 in Norway, when the weather permitted.[105]

On the 14 August, Sperrle began a smaller, prolonged, but widely scattered series of attacks on aerodromes and other targets in the western half of England. The attacks were not very effective and earned the Luftflotte a rebuke from Göring.[106] The following day, between midnight and midnight, the Luftwaffe made 1,786 sorties. Conferring with his commanders, Göring condemned the lack of foresight which had sent many bombers of Luftflotte 3 on difficult missions suitable only for experienced picked crews. The Reichsmarshall also deplored the waste of effort caused by choosing targets of no strategic value as 'alternatives' for crews unable to reach their primary objectives.[107] The 15 August became known as "Black Thursday" in the Luftwaffe due to the scale of the fighting and losses.[108]

The 18 August 1940—known as The Hardest Day—proved disastrous for Sperrle's air fleet. Luftflotte 3 had poor intelligence; the British airfields the Air Fleet attacked had nothing to do with the battle for air superiority, for they belonged to RAF Coastal Command and Fleet Air Arm.[109] Sperrle and his command remained unaware of the intelligence failures, and as one analyst remarked, they "literally did not know what they were doing. Any grass landing strip with a few buildings around it seemed to warrant a raid."[110] From, the tactical perspective, improper positioning of Sperrle's fighter leaders allowed RAF pilots to mass attacks against isolated elements of dive-bombers, causing heavy losses.[109] On 24 August Göring ordered Sperrle to conduct bombing operations against Liverpool, a major port city. Three days later, he decreed Sperrle's air fleet was to be used for night attacks exclusively and siphoned his fighter units off to Kesselring.[111] 450 tons of bombs damaged the docks and damaged HMS Prince of Wales.[112] Twenty-four hours earlier, Sperrle's last major daylight attack for several weeks against Portsmouth was repulsed by Park's 11 Group.[113][114]

On the night of 28 August Luftflotte 3 attacked Liverpool. The night's bombing was reckoned the first major night attack on the United Kingdom. The process was repeated for three nights. Luftflotte 3 sent an average of 157 bombers a night to Liverpool and Birkenhead. About 70 percent of crews claimed to have dropped, on each night, an average of 114 tons of high explosive and 257 incendiary bombs. On 29 August 176 crews were sent, of whom 137 claimed to have reached the Mersey ports and to have dropped there 130 tons of high-explosive and 313 incendiary-canisters. For Luftflotte 3 the four raids involved the biggest effort they could make without impairing their capacity to operate for weeks to come. On the third night only some 40 tons of high explosive fell on Liverpool, Birkenhead, or close by. The docks were not hit and damage was mostly to suburban property. Sperrle lost only seven crews, reflecting the parlous state of RAF night fighter defences.[115]

At the beginning of September 1940, Sperrle could muster 350 serviceable bombers and dive-bombers and about 100 fighters, either for his own purposes or to support the 9th Army and, if necessary, the 6th Army in a landing. Sperrle lost Richthofen to Kesselring who took possession of some units in Normandy, and concentrated the available dive-bomber force near the Straits of Dover.[116] Sperrle was sceptical about Fighter Command's reported losses. He had seen inflated claims made before in Spain, and advocated maintaining attacks on the RAF and the infrastructure supporting it. This strategy was about to change.[117]

The battle over airfields continued into September. On the third day, Göring met with Sperrle and Kesselring. Göring was sure Fighter Command was exhausted and favoured attacking London to draw out the last of the British fighter reserves. Kesselring enthusiastically agreed; Sperrle did not.[118] Kesselring urged Göring to carry out an all–out attack[119] based on the unproven assertion that Fighter Command had been virtually destroyed. Sperrle dismissed Kesselring's optimism, and put British strength at the more accurate figure of 1,000 fighters.[120] Nevertheless, Kesselring's perception prevailed. The disagreement between the two air fleet commanders was not uncommon, and although they rarely quarrelled, their commands were separate and they did not coordinate their efforts. Instead, they fought their own private campaigns.[121]

The focus of air operations changed to destroying the docks and factories in the centre of London.[118] The change in strategy has been described as militarily controversial. The decision certainly relieved the pressure on Fighter Command, but wartime records and post-war analysis has shown that Fighter Command was not on the verge of collapse as assumed by German intelligence.[122][123][124][125] The consequences for Luftwaffe airmen were severe on 15 September 1940. German aviators met a prepared enemy[126] and crew losses were seven times that of the British.[127] Furthermore, Fighter Command did not commit its reserve during the main attacks as the German command predicted.[127]

The Blitz

The bombing operations continued against Fighter Command into October 1940, but with gradually more emphasis placed on attacking industrial cities, primarily because it offered the only way to continue hostilities against Britain directly in the absence of invasion. Air strategy became increasingly aimless and confused. The damage to the British war economy and morale was minimal into 1941.[128] The preference for night over day operations was evident in the number of bombing operations flown by the German air fleets. In October 1940, 2,300 sorties were flown in daylight and 5,900 at night, reducing losses from 79 in day operations to 23 at night. Sperrle's command flew the majority of the missions; 3,500 to Kesselring's 2,400.[112]

Sperrle's air fleet received Fliegerkorps I in late August 1940. The corps contained specialist units equipped with Y-Verfahren (Y-Control), a night navigational aid which precipitated the Battle of the Beams.[129] Several of Greim's air corps were assigned pathfinder units from KG 26 and KG 55 known as Beleuchtergruppe (illumination group).[130] Sperrle had spent the last week of August and first week of September gearing up for large–scale night operations. Sperrle's air fleet assisted in the beginning of The Blitz which began in earnest on 7 September 1940. This night approximately 250 aircraft dropped 300 tons of high explosive and 13,000 incendiaries on the centre of London.[131]

Sperrle's airmen flew 4,525 bombing operations in November 1940.[132] The air fleet played a large role in the Birmingham and Coventry Blitz, with support from Luftflotte 2. Sperrle provided 304 of the 448 bombers in the Coventry attack. Surviving German records suggest that the aim of the Coventry raid was to disrupt production and reconstruction critical to the automotive industry, but also to dehouse workers.[133] 503 tons of high explosive and oil bombs were dropped by the 449 crews that claimed to have hit the target.[134] The destruction of the city centre cost the air fleet one bomber.[135]

In November, 159 bombers from Luftflotte 2 and 3 bombed Southampton destroying much of the city. Bombers attached to the air fleet led attacks on Birmingham, part of 357-strong force. Incendiaries started fires that were visible from 47 miles (76 kilometres) away. The air fleet was involved in attacks on Liverpool (324 bombers).[136] Over 20–22 December 205 and 299 bombers struck the city.[137] The bombing, on targets such as Liverpool, were not followed up the next night, giving the city, inhabitants and defences time to recover.[138] Ministry of Home Security Herbert Morrison warned that morale in the city might crumble under sustained bombing—he did report 39,126 grt of shipping had been sunk, 111,601 grt damaged. Half the berths were out of action and unloading capacity was reduced by 75 percent.[139]

In December 1940 Sperrle's air groups flew 2,750 bombing operations against British cities, more than the 700 flown by Kesselring's command.[112] Manchester—in close proximity to Liverpool—was first bombed in December 1940, beginning the Manchester Blitz.[140] From 22 to 24 December Manchester was bombed on two successive nights by 270, then 171 bombers.[137] Northern targets were expanded to include participation in the Sheffield Blitz. On 12 December the bombing of the city opened with attacks by 336 aircraft then a further 94 two days later.[137] The bombing was carried out over the course of nine hours, destroying much of the city.[141] London remained a primary objective. On the night of 9 December 1940, for example, 413 bombers hit the capital and on 29 December the bombing caused what became known as the Second Great Fire of London.[137] On this night alone Sperrle's air fleet dropped 27, 499 incendiaries. It was not the heaviest raid on London—136 aircraft—but it was the most destructive.[142]

On 24 November 1940 148 of Sperrle's bombers began the Bristol Blitz. Around 12,000 incendiary bombs and 160 tons of high-explosive bombs were dropped. Park Street destroyed and the Bristol Museum hit. 207 people were killed and thousands of houses were destroyed or damaged.[143] The city was targeted again on 3/4 January 1941.[144] 30 air raids were carried out against Bristol according to wartime British sources. Approximately a little over 1,000 people were killed in the attacks.[145] By January 1941, Luftflotte 3 had been reorganised. I. Fliegerkorps under Generaloberst Ulrich Grauert remained with Sperrle, but he was given two further air corps—VI. Fliegerkorps under Generalleutnant Kurt Pflugbeil and V. Fliegerkorps under General Greim was retained; eight bomber wings provided the striking power of Sperrle's air fleet.[146]

In February 1941 bad weather limited Sperrle to 975 bombing operations.[112] Bomber wings under Sperrle's command struck at Swansea. 101 high explosive and several hundred of other types of bombs were dropped disrupting the Great Western Line.[147] In March the intensy of bmbing operations increased, Luftflotte 3 flew 2,650 operations.[112] Attacks against Cardiff in March 1941 caused some of populace to evacuate the city, a phenomenon known as "trekking".[148] Such incidents caused only temporary drops in morale.[148] Other bombing operations were carried out against Liverpool by 316 aircraft, Glasgow by 236, Bristol by 162 bombers, London by 479 aircraft Portsmouth by 238 and Plymouth over two nights by 125 and 168 bombers.[149]

In April 1941 the Midlands bore the brunt of German bombing raids with only three nights respite, 75 percent of them carried out by Sperrle's air fleet.[148] Birmingham was bombed on consecutive nights by 237 and 206 aircraft. Coventry was also subjected to a 237-bomber attack.[150] British ports were also targeted as part of 16 major and five heavy attacks.[150] Plymouth, Glasgow and Belfast were bombed in mid-April and morale was severely effected.[139] Plymouth was bombed on five of the eight nights from 21 to 30 April by 120, 125, 109, 124 and 162 aircraft.[150] The Port of London was bombed by 685 aircraft on 16 April and by 712 on 20 April.[150] April was the most intensive month of the Blitz for Luftflotte 3 in 1941—approximately 3,750 bombing operations in comparison to 1,500 by Kesselring's air fleet.[112]

In May 1941, the final full-month of the German night offensive, Luftwaffe forces operating against western cities in Britain bombed Dublin, ostensibly in error. Luftflotte 3 regularly operated over North West England, against Liverpool and Manchester. On 31 May 1941, Sperrle's air fleet made a huge navigational error, and bombed the Irish capital, situated some 200 miles from their targets in Liverpool.[151] During May units belonging to the air fleet were involved in the Hull and Nottingham Blitz.[152] A last effort was made against London on 10 May. 571 bombing missions were flown against the embattled capital that night.[153] During the month, Sperrle's men carried out the burden of night operations, flying 2,500 sorties in comparison to 1,300 from Luftflotte 2.[112]

Approximately 40,000 British civilians had been killed, another 46,000 injured, and more than a million houses damaged during the Blitz. The German air fleets lost 600 German aircraft on night operations. The Coventry raid, which for a short time caused a decline of 20 percent of aircraft output, recovered. The effect on general industrial production was not significant. In five months of bombing docks and ports in 1941, only some 70,000 tons of food stocks were destroyed, and only one half a percent of oil stocks. Damage to communications was quickly repaired. Everywhere except in the aircraft industry the loss was too small a fraction of total output to matter seriously.[154]

In early June 1941, the majority of German bomber units moved eastward to the soon-to-be Eastern Front, in preparation for Operation Barbarossa. Luftflotte 2, with elements of Sperrle's air fleet—from IV and IV Fliegerkorps—were reassigned.[155]

Battle of the Atlantic

Sperrle had been involved in the war at sea since the first phase of the Battle of Britain. He received an OKL directive on 20 October 1940 ordering him to attack shipping once again in the Thames Estuary. He ordered his dive-bombers into this service, but they were rapidly neutralised in November by a "dynamic defence".[156] The most effective support for the U-boat campaign came from attacking ports, which Directive 23, issued on 6 February 1941, had ordered the German air fleets to do.[157][158] Direct support to the Kriegsmarine in the Battle of the Atlantic was haphazard; successes were won by accident rather than by design.[157] In late May 1941 Luftflotte 3 made a sole contribution to the surface fleet, when it tried, in vain, to save the battleship Bismarck.[159]

Within days, 41 of the 48 bomber groups engaged in operations over Britain departed for the soon-to-be Eastern Front in preparation for Barbarossa.[155] Of the remaining seven, five were to support the Kriegsmarine in the Battle of the Atlantic under the command of Fliegerführer Atlantik (Flying Leader Atlantic).[155] The Atlantic command came under Sperrle's control upon formation[160] but was subordinated to Sperrle officially on 7 April 1942.[161] The name of the command was misleading, for it was tasked with maritime interdiction operations all around the British coast besides operating deep into the Atlantic.[162]

Only two bomber groups remained under Sperrle's command at the end of 1941 for direct attack on Britain.[161] The anti-shipping mine-laying force around Britain did not receive the support it required through the war, and the German effort remained half-hearted. Sperrle protested to the OKL, OKW and Göring upon the dissipation of mine-laying operations through 1941 and 1942. Greim's air corps was designated as leader of the effort in an effort to revitalise the campaign, but due to the demands of the Eastern Front, Greim departed in December 1941.[163]

In the 46 months following July 1940, German aircraft sank 1,228, 104 tons of merchant shipping and damaged 1,953, 862 tons. Another 60, 866 tons were sunk or damaged by mines in 1942 and 1943.[164] The failure to properly cooperate with the navy against shipping was a grave strategic error which prevented the achievement of greater results.[164][165] Göring's intransigence was large factor in reducing the air effort.[166] In May 1942, Fliegerführer Atlantik had only 40 aircraft and IX. Fliegerkorps, under Sperrle's command at Soissons, 90.[167] The U-boat arm continued to press for greater air protection in the Bay of Biscay.[167] In 1942, anti-shipping operations near the British coast proved too expensive, and the demands of the Mediterranean Theatre and Eastern Front diverted some of the precious Focke-Wulf Fw 200s. These aircraft would not return for Atlantic operations until the summer, 1943.[168]

For a brief period in March 1943—before the German defeat in Black May—Sperrle intended to increase his command to 22 groups (equivalent to seven Geschwader, or wings) for Atlantic operations. Ulrich Kessler, commanding Fliegerführer Atlantik, estimated that with Sperrle's proposed bomber forces, he could sink 500,000 tons of shipping per month. Kessler did not receive adequate support, despite the optimisim of their meeting.[169] On 5 June, Sperrle informed the naval command that the rescue of sunk U-boat crews was to take precedence over aerial reconnaissance of convoys.[170] Making matters worse, the Luftwaffe did nothing effective to counter RAF Coastal Command's Bay of Biscay offensive against U-boat transit routes.[170] From the Allied perspective, the Atlantic campaign became nothing more than a "skirmish" by the autumn, 1943.[171]

The situation reached a climax in 1944. Kessler joined Karl Dönitz in outlining the hopeless military situation facing his Atlantic command. Göring was sensitive to criticism of the Luftwaffe in front of Hitler, and hastily removed him from command on 7 February 1944. The command was disbanded officially three weeks later. The remnants were subsumed into X. Fliegerkorps.[172] From 19 February to April 1944, there was a virtual absence of Luftwaffe reconnaissance over the Atlantic.[173] Atlantic operations continued until 13 August 1944, when the headquarters of II. Fliegerkorps evacuated their Atlantic base at Mont-de-Marsan, despite contrary order's from Sperrle's staff once the German Western Front began to collapse.[174]

Circus offensives, Baedeker Blitz, Mediterranean

Sperrle commanded all German air forces in France, Netherlands and Belgium upon the departure of Kesselring in mid–1941. At this time, Sperrle was permitted to keep two Luftgaue in southern Germany under his control to appease his "vanity".[175] Luftflotte 3 became solely responsible for maintaining the pressure on British cities, sea communications and protecting German-occupied territory from RAF incursions, named the Circus offensives. The RAF Circus offensives were the brainchild of Air Chief Marshal Sholto Douglas, Air Officer Commanding Fighter Command and his principal lieutenant, Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, using Park's No. 11 Group. It formed the Air Staff's policy of "leaning" into Europe.[176] Fighter Command began with Circus Number 1 on 10 January 1941.[177]

Sperrle was stripped of most of the fighter forces leaving only two wings—JG 2 and JG 26.[178] The two fighter wings covered the coast from Brittany to eastern Belgium. They would carry the burden of air defence in 1941 and 1942.[179] Kesselring's departure left Jagdfliegerführer 2 (Fighter Flyer Command 2) under Theo Osterkamp responsible for air space from the Schelde to the Seine. Werner Junck inherited Jagdfliegerführer 3 which defended air space to the west of the Seine. Karl-Bertram Döring commanded Jagdfliegerführer 1 covering the Netherlands—each leader controlled a wing; JG 26, 2 and 1 respectively.[180] JG 1 was added to Sperrle's command by 10 July 1942.[181] Sperrle had only two bomber wings under his command—one of which formed part of Fliegerführer Atlantik.[181]

Between mid-June and the end of July 1941, Fighter Command flew some 8,000 offensive sorties, covering 374 bombers. They claimed 322 German aircraft for the loss of 123. Sperrle's forces lost 81 fighters from the approximate total of 200 in France and Belgium. The strength of the two fighter Geschwader fell to 140 in August 1941 and serviceability within these totals from 75 percent to 60 percent.[182] July and August proved to be the busiest, with 4,385 and 4,258 interceptions.[183]

From July to December 1941 Circus operations cost Fighter Command 416 fighters in 20,495 sorties and RAF Bomber Command 108 in 1,406.[184] Sperrle's fighters flew 19,535 sorties and lost 93 in the same period.[185] Fighter Command claimed 731 German aircraft from 14 June to December 1941 whereas actual German losses were 103 leading post-war RAF analysis to conclude it lost four aircraft and 2.5 pilots for every German fighter destroyed.[185] Rather than wear Luftflotte 3 down, the number of German fighter aircraft in the west increased from 430 on 27 September 1941 to 599 on 30 September 1942.[184]

The new year of 1942 began with a continuation of the 1941 successes. In February 1942, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Prinz Eugen escaped from the French port at Brest in Operation Cerberus upon their return from the recent Operation Berlin. One of Sperrle's former wing commanders, General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland, planned Operation Donnerkeil, an air superiority plan with Sperrle's chief of staff Karl Koller. From the Luftwaffe's perspective, the operation was a success against the odds. Sperrle was able to provide five bomber groups for the Donnerkeil.[186]

The Circus offensive in 1942 succeeded in putting Sperrle's air defences under pressure. Fighter Command flew 43,339 daylight sorties over Western Europe and Bomber Command 1,794.[187] The largest air battle occurred on 19 August 1942 during the Dieppe Raid. Luftflotte 3's units won a significant victory over Fighter and Bomber Command. The British lost 106 aircraft; the Germans lost only 48 aircraft destroyed and 24 damaged.[188][189] At the end of 1942, Leigh-Mallory replaced Douglas as AOC Fighter Command. The two men had presided over the loss of 587 fighters while Sperrle lost 108 through the year. The British losses were equivalent to 30 squadrons.[190]

The Luftwaffe did not remain on the defensive in 1941 and 1942. Sperrle's air fleet carried out intensive air attacks on Britain and the limited German bomber force was reinforced over the winter, 1941–42. Concurrently, Sperrle with support from Hans-Jurgen Stumpff, continued to carry out air attacks on shipping.[191] The Baedeker Blitz became the largest air offensive against Britain in 1942. The campaign was prompted by the bombing of Lübeck. Hitler ordered Sperrle to bomb British cities that held cultural significance. Hitler specifically outlined the terrorist purpose of the bombing offensive aimed at civilian centres for the greatest impact on the British populace.[192][193] The blitz was accompanied by fighter-bomber attacks against London and coastal towns, which took place until June 1943. In April 1943, Sperrle's air fleet could still muster 120 aircraft for these operations.[194] The purpose of these fighter-bomber (Jabo) operations, which began from autumn, 1942, was for "reprisals", similar to the German bomber campaign.[191]

On 23 April 1942 the Baedeker offensive began with the Exeter Blitz and the Bath Blitz and extended west to Norwich. KG 2 carried the burden of campaign. In the Bath operation Sperrle's pilots flew at only 600 ft (180 m) to magnify the damage. York was attacked and the cities suffered as German crews flew several missions per night. The offensive was halted on 9 May. Sperrle's bombers had suffered a 5.3 percent loss rate in 716 missions, a loss of 38 bombers. Bombing operations continued upon the cessation of Baedeker against Birmingham in July and Canterbury.[195] Luftflotte 3 flew 2,400 night bomber sorties against Britain in 1942 and lost 244 aircraft; a loss rate of 10.16 percent.[195] During the operations, Sperrle's wing commanders were forced to draw upon increasing numbers of instructor pilots—IV./KG 55, for example, lost a quarter of them.[195] Sperrle's air fleet flew 7,039 bombing operations and dropped 6,584 tons of bombs.[195]

On 8 November 1942, Anglo-American forces landed in North Africa (Operation Torch). Hitler ordered Sperrle's forces to occupy the French-Mediterranean coast (Case Anton).[196] The aerial component of Anton was Operation Stockdorf. Sperrle's command in the south was Fliegerdivision 2 commanded by Johannes Fink. Eight bomber and two fighter groups (approximately 30 aircraft in each) were selected for reconnaissance and anti-shipping operations by his order, dated 2 November. The air forces were to support the army, destroy any French aerial resistance and carry out interdiction of supply lines. Aside from anti-aircraft fire near Marseille, no serious resistance was encountered. The invasion provided bases for Sperrle's fleet to strike at shipping in the Mediterranean Sea but left him with only four fighter groups to defend northern France.[197] Luftflotte 3's headquarters remained in France but it provided three bomber groups to Richthofen—commanding Luftflotte 2—for the defence against the Allied invasion of Sicily.[198]

The Luftwaffe continued to defend Western Europe in 1943 as its offensive capabilities declined. The Jabo operations came to a halt in the summer, 1943 due to excessive casualties and the need to reinforce the Mediterranean. German bomber units flew less than 4,000 individual bomber sorties during the entire year. In March 1943, Hitler ordered the appointment of an officer to coordinate attacks on Britain. Dietrich Peltz was given command of IX Fliegerkorps, part of Sperrle's air fleet for this task. By December 1943 Peltz had pooled 501 bombers.[199] As Peltz organised the bomber command, German operations against Britain continued. The year began with 311 sorties in January 1943 which dipped to 176 the following month. It reached 415 in March before peaking with 537 sorties in October 1943 and concluding with 190 in December. That year 3,915 night bombing sorties were flown, costing 191 aircraft—March being the worst month with 38.[200] The Jabo units flew 728 sorties and lost 65 aircraft. The total tonnage of bombs dropped was recorded as 3,576.[200]

Defence of the Reich and Steinbock

In 1942 another threat emerged when the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) began bombing raids against targets in Belgium and France.[201] The first operation was carried out on 29 June 1942.[202] On 27 January 1943 it extended the American area of operations into Germany for the first time.[203] In 1942 the USAAF flew 1,394 bomber and 1,081 fighter sorties over Western Europe.[190] Sperrle's fighter pilots carried the burden of the defence in 1942. Later that year, JG 1 was assigned to Luftwaffenbefehlshaber Mitte, later known as Luftflotte Reich (Air Fleet Reich) but saw little action since USAAF rarely crossed into the Netherlands.[201] Thereafter, the air war only escalated. Sperrle resisted attempts by Luftwaffenbefehlshaber Mitte to gain control of anti-aircraft forces or to allow the physical degradation of his air fleet, and the offensive mindedness of the OKL favoured front-line units.[204] Eventually, Luftflotte 3 lost Luftgaue VII, XII and XIII's anti-aircraft units.[205]

Luftflotte 3's order of battle contained only one complete fighter wing on 10 June 1943 and one group each from two other wings along with two independent squadrons (staffeln). The only fighter-bomber unit left was SKG 10, under the command of IX Fliegerkorps. The sole combat unit under Höherer JagdfliegerführerWest commanded by Max Ibel was I./JG 27. Jagdfliegerführer 2 under Generalmajor Joachim-Friedrich Huth contained only II./JG 26 and three other squadrons.[206]

On the same date the Combined Bomber Offensive began around the clock bombing of German-occupied Europe—the defence of these regions became known as the Defence of the Reich. The purpose of the offensive was to destroy the Luftwaffe and its supporting facilities in Europe through aerial bombardment and the destruction of German fighter defences in combat. Air superiority was to be achieved before Operation Overlord.[207] The US Eighth Air Force operations created a crisis in July and August 1943.[208] In March 1943, an immediate rise in losses had already been noted. A report from Luftflotte 3 recognised the size and defensive power of American bombers required a timely interception by massed formations for any chance of success. In July alone, western fighter forces lost 335 single-engine aircraft to all causes—18.1 percent of the available strength reported on 1 July.[208] There was also a noticeable decline in the quality of pilot training.[209]

On the German side, there was a call to unify German fighter forces and hold them back from the coast and keep them out of Allied fighter escort range. Regardless of the logic, Sperrle opposed the idea to preserve his command.[210] Sperrle was sensitive to a centralised command for fighter forces and resisted. On 14 September 1943, the Luftflotte 3 area of operations covered most of France, with the exception of some regions in Alsace-Lorraine; Luxembourg, western and southern Belgium were his responsibility.[205] Sperrle's headquarters remained in Paris. The largest organisation attached to Sperrle's command was 3. Jagd Division (3rd Fighter Division) based at Metz, under the control of Werner Junck.[205][211] Sperrle had retained the Luftgaue in southern Germany and his air fleet was given control of the 5. Jagd Division.[211] On 15 September 1943 to improve Sperrle's organisation the II. Jagdkorps was formed with the 5th and 4. Jagd Division. The improvement in command and control made little difference in the battle with the USAAF for neither division received the reinforcements it needed.[212]

From November 1942 – August 1943, the OKL missed a last chance to build a reserve to contest air superiority in the coming battles. The unwillingness of German air leaders to trade space for time forced the Luftwaffe into a battle of attrition that it could not win.[213] At the end of 1943, the German air defences won temporary successes against the USAAF Eighth Air Force—the Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission and Second Raid on Schweinfurt were defensive victories won at an exorbitant cost and with Sperrle's peripheral involvement.[214] In February 1944, Big Week targeted German and French–based targets. The German fighter force was bled white over the following two months.[215] Before June 1944, Luftflotte 3 remained weak and contained few ground-attack aircraft; nearly all were based on the Eastern Front. Sperrle's fighter pilots were required to attack the landing forces.[216] Reinforcements came from Luftflotte Reich, but none of the pilots had been trained for ground-attack operations.[216]

A major effect of the combined offensive on Sperrle's air fleet was the diversion and reinforcement of Luftflotte Reich at the expense of Luftflotte 3. By June 1944, the number of fighter aircraft available in the west numbered 170.[217] Sperrle's air fleet had, at most, 300 fighter aircraft on 6 June 1944 to contest the D-day landings.[218] The Western Allies amassed 12,837, including 5,400 fighters.[218] The air fleet was particularly weak in night fighter units. Given the low priority for their production, Sperrle went for periods with no night–fighting capabilities despite the crucial geographical position of his air fleet and the exposure of important French industries to night attack.[219] The diversion of resources extended to anti-aircraft artillery. On 14 May 1944, the OKL cancelled an order to divert five heavy and four light or medium batteries, each from Luftflotte 1 and 6, to Sperrle and instead rerouted them to Luftflotte Reich.[220] Sperrle did retain the III Flak Corps which could be used in ground combat.[221]

Another facet of the air war was the night offensive against Germany. Bomber Command's area attacks against German industrial cities enraged Hitler and he ordered Sperrle to use Peltz's bombers to strike back.[164] Sperrle's air fleet was reinforced on Göring's orders for the purpose of bombing London. The offensive was named Operation Steinbock and began in January 1944.[222] The operational aspects were devised by Peltz. He remarked to Göring that he would need any aircraft capable of carrying a bomb. By December 1943, Peltz assembled 695 operational aircraft before the offensive.[223] Of the aircraft, 467 were bombers, 337 of them operational. On 20 January 1944 this increased to 524, with 462 combat ready.[224] Peltz was subordinated to Göring, bypassing Sperrle, who Hitler and Göring regarded as sybarite by this stage.[225] The feeble offensive was mocked by the British, and Peltz' forces incurred a 10 percent loss rate per sortie, for little military gain and 329 bombers were lost.[226][227] The offensive wasted the last German bomber reserves.[228] The losses were a blow to Sperrle. He had wanted to use his bomber forces to attack the invasion forces during the night at the landing grounds and the embarkation points in England.[229] Hitler and Göring rejected this strategy as "too passive".[230]

Normandy and dismissal

Sperrle's air fleet Enigma signals had been cracked and ULTRA codebreakers from Bletchley Park deciphered signals sent by Luftflotte 3 headquarters to the OKW. Reading the reports, Allied intelligence deduced that the bombing operations against bridges, west of the Seine, and fighter activity between Mantes and Le Mans, had convinced the air fleet staff the invasion would take place in the Pas de Calais. The air fleet reports, dated 8 and 27 May 1944, expressed the view this activity pointed "unmistakably" towards that conclusion. Operation Fortitude reinforced that belief.[231]

Allied attacks in May 1944 against bases had a devastating impact on Luftflotte 3 capabilities. ULTRA gave the Allies intelligence on the location and strength of German fighter units as well as the effectiveness of attacks. They knew when repairs to bases had been completed and when the Germans decided to abandon particular locations. The Allies pursued an intensive, well-planned campaign that destroyed the German structure near the English Channel and invasion beaches and forced Sperrle's air fleet to abandon efforts to prepare bases close to the Channel.[232] Further damage was done to Sperrle's air defence network. Some 300,000 personnel worked in Luftflotte 3, 56,000 in signals. The fortification of radar sites after Dieppe had only highlighted them, and 76 of the 92 were knocked out by D-Day, blinding his Jagdkorps.[233]

From December 1943, the Germans planned to move reinforcements into Luftflotte 3 when the invasion occurred so it could then launch a decisive air attack against the landings in the first hours.[216] The plan, known as Operation Dr Gustav unravelled immediately due to ULTRA intercepts learning the date and time of reinforcements.[234] The Allied air offensive had devastated German fighter bases and units while Steinbock had removed the bomber force from the battle.[235]

On 5 June, the eve of the Normandy Campaign, Luftflotte 3 contained 600 aircraft of all types. It was expected that Luftflotte Reich would send forces to France. German meteorological reports misread the weather so that the invasion caught the command by surprise.[216] Of his total strength, only 115 single-engine fighters were operational with 37 twin-engine fighters, 137 bombers, 93 anti-shipping aircraft, 48 ground-attack and 53 reconnaissance aircraft. Only 56 night fighters were combat ready in France.[236] Sperrle's anti-shipping force, Fliegerkorps X, consisted of only 137 conventional bombers, a force totally inadequate to counter Allied naval forces.[237] On 23 May 1944, Sperrle had 349 heavy and 407 Flak batteries at his disposal.[238]

The Allies enjoyed air supremacy on 6 June 1944 and flew 14,000 missions in support of the invasion. On the first day, the British and Commonwealth landed 75,215 men and the Americans 57,500. A large force of 23,000 paratroops parachuted in during the night.[216] Luftflotte 3 barely reacted. Nevertheless, Sperrle issued a pompous order of the day to his airmen:

Men of Luftflotte 3! The enemy has launched the long-announced invasion. Long have we waited for this moment, long have we prepared ourselves, both inwardly and on the field of battle, by untiring, unending toil. Our task is now to defeat the enemy. I know that each one of you, true to his oath to the colors, will carry out his duties. Great things will be asked of you, and you will show the bravest fighting valor. Salute the Führer.[216]

Sperrle's sentiments were delusional. Luftflotte 3 launched less than 100 sorties including 70 by single-engine fighters. During the evening and night, bombers and anti-shipping squadrons mounted 175 more sorties against the invasion fleet. Sperrle lost 39 aircraft with 21 damaged, 8 due to non-combat causes.[216]

Luftflotte 3 received 200 fighters from Germany within 36 hours of the invasion. An additional 100 followed by June 10. Their effectiveness was reduced by the destruction of air bases which forced units to deploy to inadequately prepared airfields.[239] Most of the 670 aircraft that reinforced Sperrle were used up as air bases were under constant attack and the anti-shipping effort failed.[240]

ULTRA monitored the movements of air units. On the night of June 7/8, the bomber and anti-shipping aircraft managed to fly 100 sorties, while the day forces flew 500 on 8 June—400 by single-engine fighters; Luftflotte 3 lost 68 aircraft during the day. In the first week of operations 362 aircraft were lost. In the second week, another 232 aircraft were destroyed. Thus, in the two weeks from 6 to 19 June, they lost nearly 75 percent of the aircraft that Luftflotte 3 had possessed on 5 June.[239] From 6 to 30 June the Germans had lost 1,181 aircraft in 13,829 sorties.[241] Of those sorties flown, 9,471 were fighter sorties.[238]

German fighters loaded with bombs were unable to defend themselves and suffered heavy losses. They accomplished little, and soon fighter units ceased ground-attack operations.[242] Luftflotte 3 used the latest novelty weapons in a bid to attack Allied shipping—the Mistel, Messerschmitt Me 262 and Henschel Hs 129 debuted in June and July 1944 in very small numbers.[243] Radio-guided missiles sank just two vessels and damaged seven in Normandy. Torpedo aircraft sank two and damaged only three more. The anti-shipping effort was a failure.[244] Some 1,200 attacks against shipping and 900 mine-laying operations were made in June, to little effect.[245]

On 9 July ULTRA intercepted messages from Sperrle notifying his units that "ruthless" fuel economy measures be made and forbade the non-essential expenditure of fuel.[246] Another decrypted message from Luftflotte 3 to OKL stated that air attacks had depleted fuel stocks to such an extent that June's allocation would have to last to the end of July.[247] II. Jagdkorps was ordered by Sperrle to cease ground-attack and night operations in August owing to the fuel crisis.[248] In August 1944, as the German army retreated from France, Sperrle's air fleet could fly only 250 missions to cover it.[245]

The performance of Sperrle's III Flak Corps was an exception.[249] The Allied air forces lost 1,564 aircraft in June 1944, the majority to flak. The losses forced a reduction of activity in July and August 1944. The US Ninth Air Force command was critical of German fighter defences but noted that flak defences were effective and the source of constant attrition.[241] The American air command suffered a 10–15 percent monthly attrition rate from April to July 1944.[241]

Sperrle was dismissed from his post on 23 August 1944,[250] hours before American and French forces liberated Paris and overran his headquarters. As the German front collapsed in the aftermath of the Falaise pocket, the air fleet ground organisation fled east across the Seine. Hitler charged the personnel of Luftflotte 3 with desertion and held Sperrle responsible. On 22 September 1944 his former command was downgraded from air fleet to air command.[251]