History of communication studies

Various aspects of communication have been the subject of study since ancient times, and the approach eventually developed into the academic discipline known today as communication studies.

Pre-20th century

In ancient Greece and Rome, the study of rhetoric, the art of oratory and persuasion, was a vital subject for students. One significant ongoing debate was whether one could be an effective speaker in a base cause (Sophists) or whether excellent rhetoric came from the excellence of the orator's character (Socrates, Plato, Cicero). Through the European Middle Ages and Renaissance grammar, rhetoric, and logic constituted the entire trivium, the base of the system of classical learning in Europe.

Communication has existed since the beginning of human beings, but it was not until the 20th century that people began to study the process. As communication technologies developed, so did the serious study of communication. When World War I ended, the interest in studying communication intensified. The social-science study was fully recognized as a legitimate discipline after World War II.

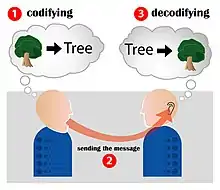

Before becoming simply communication, or communication studies, the discipline was formed from three other major studies: psychology, sociology, and political science.[1] Communication studies focus on communication as central to the human experience, which involves understanding how people behave in creating, exchanging, and interpreting messages.

United States

1900s–20s

Though the study of communication reaches back to antiquity and beyond, early twentieth-century work by Charles Horton Cooley, Walter Lippmann, and John Dewey have been of particular importance for the academic discipline as it stands today. In his 1909 Social Organization: a Study of the Larger Mind, Cooley defines communication as "the mechanism through which human relations exist and develop—all the symbols of the mind, together with the means of conveying them through space and preserving them in time." This view gave processes of communication a central and constitutive place in the study of social relations. Public Opinion, published in 1922 by Walter Lippmann, couples this view with a fear that the rise of new technologies in mass communication allowed for the 'manufacture of consent,' and generated dissonance between what he called 'the world outside and the pictures in our heads,' referring to the rift between the idealized concept of democracy and its reality. John Dewey's 1927 The Public and its Problems drew on the same view of communications, but instead took a more optimistic reform agenda, arguing famously that "communication can alone create a great community," as well as "of all affairs, communication is the most wonderful."

Cooley, Lippmann, and Dewey capture themes like the central importance of communication in social life, the impact of changing technology upon culture, and questions regarding the relationship between communication, democracy, and community. These concepts continue to drive scholars today. Many of these concerns are also central to the work of writers such as Gabriel Tarde and Theodor W. Adorno, who have also made significant contributions to the field.

In 1925, Herbert A. Wichelns published the essay "The Literary Criticism of Oratory" in the book Studies in Rhetoric and Public Speaking in Honor of James Albert Winans.[2] Wicheln's essay attempted to "put rhetorical studies on par with literary studies as an area of academic interest and research."[3] Wichelns wrote that oratory should be taken as seriously as literature, and therefore, it should be subject to criticism and analysis. Although the essay is now standard reading in most rhetorical criticism courses, it had little immediate impact (from 1925 to 1935) on the field of rhetorical studies.[4]

1930s–50s

The institutionalization of communication studies in U.S. higher education and research has often been traced to Columbia University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where early pioneers such as Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Harold Lasswell, and Wilbur Schramm worked. The work of Samuel Silas Curry, who founded the School of Expression in 1879 in Boston, is also noted in early communication research. Today, the School of Expression is known as Curry College, located in Milton, MA, which houses one of the nation's oldest Communication programs.[5]

The Bureau of Applied Social Research was established in 1944 at Columbia University by Paul F. Lazarsfeld. It was a continuation of the Rockefeller Foundation-funded Radio Project that he had led at various institutions (University of Newark, Princeton) from 1937, which had been at Columbia as the Office of Radio Research since 1939. In its various incarnations, the Radio Project had involved Lazarsfeld himself, and people like Adorno, Hadley Cantril, Herta Herzog, Gordon Allport, and Frank Stanton (who went on to be president of CBS). Lazarsfeld and the Bureau mobilized substantial sums for research, and produced, with various co-authors, a series of books and edited volumes that helped define the discipline, such as Personal Influence (1955) which remains a classic in what is called the 'media effects'-tradition.

From the 1940s and onwards, the University of Chicago was home to several committees and commissions on communications, as well as programs that educated communication scholars. In contrast to what took place at Columbia, these programs explicitly claimed the name 'communications' for themselves. The Committee on Communication and Public Opinion, also funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, was staffed with, in addition to Lasswell, people such as Douglas Waples, Samuel A. Stouffer, Louis Wirth, and Herbert Blumer, all of whom held positions elsewhere at the university. They formed a committee that essentially served as a scholarly and educational extension of the federal government's increasing interest in communications during times of war, particularly the Office of War Information. Chicago later provided an institutional home for The Hutchins Commission on the Freedom of the Press and the Committee on Communication (1947–1960). The latter was a degree-granting program that counted Elihu Katz, Bernard Berelson, Edward Shils, and David Riesman amongst its faculty, alumni include Herbert J. Gans and Michael Gurevitch. The committee also produced publications such as Berelson and Janowitz' Public Opinion and Communication (1950) and the journal Studies in Public Communication.

The Institute for Communications Research was founded at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1947 by Wilbur Schramm, who was a key figure in the post-war institutionalization of communication studies in the U.S. Like the various Chicago committees, the Illinois program claimed the name 'communications' and granted graduate degrees in the subject. Schramm, who, in contrast to the more social science-inspired figures at Columbia and Chicago, had a background in English literature, developed communication studies partly by merging existing programs in speech communication, rhetoric, and, especially, journalism under the aegis of communication. He also edited a textbook The Process and Effects of Mass Communication (1954) that helped define the field, partly by claiming Lazarsfeld, Lasswell, Carl Hovland, and Kurt Lewin as its founding fathers. He also wrote several other manifestos for the discipline, including The Science of Human Communication 1963. Schramm established three important communication institutes: the Institute of Communications Research (University of Illinois), the Institute for Communication Research (Stanford University), and the East-West Communication Institute (Honolulu). Many of Schramm's students, such as Everett Rogers, went on to make important contributions of their own.

1950s

Universities combined scholars of speech and mass media together under the term communication, which turned out to be a difficult process. While east coast universities did not see human communication as an important area for research, the field grew in the midwest. The first college of communication was founded at Michigan State University in 1958,[6] led by scholars from Schramm's original ICR and dedicated to studying communication scientifically. MSU was soon followed by important departments of communication at Purdue University, University of Texas-Austin, Stanford University, University of Iowa, and the University of Illinois. Walter Annenberg endowed three Schools for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, The University of Southern California, and Northwestern University.[7] Mass media had long been studied by Adorno and his colleagues at the University of Frankfurt, but German communication research further expanded rapidly at institutions such as the University of Hamburg, which opened the Hans Bredow Institute for Radio and Television in 1950.[8]

Associations related to Communication Studies were founded or expanded during the 1950s. The National Society for the Study of Communication (NSSC) was founded in 1950 to encourage scholars to pursue communication research as a social science.[9] This Association launched the Journal of Communication in the same year as its founding. Like many communication associations founded around this decade, the name of the association changed with the field. In 1968 the name changed to the International Communication Association (ICA).[10]

The work of what has been called 'medium theorists', arguably defined by Harold Innis' (1950) Empire and Communications grew increasingly important, and was popularized by Marshall McLuhan in his Understanding Media (1964). “McLuhan recognized that the evolution of communication played a crucial role in the human historical development and that social changes following the World Wars were directly connected with the rising of electrical communication technologies, which contributed in transforming the world into a ‘global village.’” [11] This perspective informs the later work of Joshua Meyrowitz (No Sense of Place, 1986).

Two developments in the 1940s shifted the paradigm of communication studies in the 1950s and thereafter toward a more quantitative orientation. One was cybernetics, as formulated by Norbert Wiener in his Cybernetics: Or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine.[12] The other was information theory, as recast in quantitative terms by Claude E. Shannon and Warren Weaver in their Mathematical Theory of Communication.[13] These works were widely appropriated to, and offered for some the prospect of, a general theory of society.

The tradition of critical theory associated with the Frankfurt School was, as in Europe, an important source of influence for many researchers. While done out of sociology departments, the work of Jürgen Habermas, the US-based Leo Löwenthal, Herbert Marcuse, and Siegfried Kracauer, as well as earlier figures like Adorno and Max Horkheimer continued to inform a whole tradition of cultural criticism that often focused both empirically and theoretically on the culture industry.

In 1953, to address growing needs in the industry, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute began offering a Master of Science degree in technical writing. In the 1960s the degree title became technical communication. It was the brainchild of longtime RPI professor and administrator Jay R. Gould.[14]

At the end of the 1950s Bernard Berelson remarked that the field of communication was becoming too disjointed and argued that the field was dying with no new ideas or directions. This is “often referred to as his obituary for communication research.” [15] Yet, new developments in media technology helped advance the field.

Other advances in communication studies came from the United States Information Agency and the work of Paul R. Conroy, USIA's Chief of Professional Training. As Dr. Conroy detailed in Antioch Review in 1958,[16] USIA's program to help State Department employees and other personnel position the U.S. in the best possible light helped codify—in a training environment focused on mock news conferences and other role-playing encounters—now commonly-accepted media training, crisis communication, and interpersonal communication principles.

Dr. Conroy was among the first to focus on principles of real-time message delivery - rather than simply message development - and the first to format such principles in a large-scale and repeatable training curriculum on the scale of USIA's global training program for its personnel. "It is not enough to have a clear concept of the message," Dr. Conroy summarized in Antioch Review, "Communication, after all, is an art. And since any art usually requires practice in the skilled application of sound techniques, it is better if the practice is guided rather than haphazard."

1960s

In the 1960s, Gould and his colleagues experienced increasing demand for doctoral-level studies in technical and business communication. As a result, in 1965 RPI began its Ph.D. program in communication and rhetoric. This Ph.D. degree program became a prototype for other technologically oriented programs in the United States and other industrialized countries.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the development of cultivation theory, pioneered by George Gerbner at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. This approach shifted emphasis from the short-term effects that had been the central interest of many earlier media studies, and instead tried to track the effects of exposure across time.

In the early 1960s Communication Studies began to move towards becoming a more independent field, and move out of the departments of sociology, political science, psychology, and English. The changes in the department are considered a result of the historical events taking place at the time. “Despite the different interpretations given to the changes around the time of World War II, mostly shaped by increasing technological innovations in the ways people communicate, communication became a relevant and recurrent issue in human and social science, opening the doors to the centrality of communication in social theories in the 1960s and 1970s.” [17] As a result of many of these sociological changes taking place in society, communication and mass media acquired the role of explaining these changes to the public. In response to the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam War, and other dramatic cultural shifts, critics using Marxist and feminist theory to study dominant cultures became prominent in scholarly conversations. Cultural Studies related to mass media and critics asked why a number of big organizations had such an influence on society.

The political turmoil of the 1960s worked to the field's advantage because mass media scholars began to explore the influence that media had on culture and society.[18] “Growing recognition of the importance of the media by both industry and the public, as well as increasing respect for the field at the university leveled to increased support for new scholarship.” [19] For example, national and international communications conferences started to be held and associations such as the Speech Association of America (now National Communication Association) and International Communication Association (ICA) increased membership. With each year that passed, the number of communication journals published grew rapidly and by 1970 there were nearly one hundred of them published. After 1968, communication studies started to mature into its own discipline and gained respect in developed nations.[20]

1970s–80s

The Journal of Communication referred to the 1970s as a “time of ferment, particularly in the speech field. As social scientists pushed for recognition of ‘communication’ as the dominant term, rhetorical and performance scholars reconsidered and redefined their theories and methodologies.” [21] Speech Criticism combined with other sectors such as journalism and broadcasting to form of Communication Studies. In addition to the subgroups of the field making changes, national associations frequently changed their formal names to adapt to the growing field of communication. For example, in 1970 the Speech Association of America became the Speech Communication Association.[22] Radio and television continued to develop throughout the 1970s and this boom in diversity “forced scholars to adopt a more convergent model of communication.” [23] There was no longer only one source for each message and there was almost always more than one path from sender to receiver.

Neil Postman founded the media ecology program at New York University in 1971. Media ecologists draw on a wide range of inspirations in their attempts to study media environments in an even broader and more culturally-driven fashion. This perspective is the basis of a separate professional association, the Media Ecology Association.

In 1972, Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw published a groundbreaking article that offered an agenda-setting theory that paved a new conception of short-term effects of the media. This approach, organized around additional ideas such as framing, priming, and gatekeeping, has been highly influential, especially in the study of political communication and news coverage.

The 1970s also saw the development of what became known as uses and gratifications theory, developed by scholars such as Elihu Katz, Jay G. Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch. Instead of seeing audiences as passive entities experiencing effects from a one-way model (sender to receiver), they are analyzed through the paradigm of actively seeking out content based on their own pre-existing communication needs.

In 1980 the US Department of Education classified “communication” as a practical discipline, which was associated primarily with learning journalism and media production. The same classification system deemed speech and rhetorical studies a subcategory of English.[24]

By the 1980s many colleges and universities across the country decided to rename departments to include the word “communication” in the department title. Other schools began titling their departments Mass Communication, or created independent communication departments. “Often these new schools merge the professional fields of print, broadcast, public relations, advertising, information science, and speech with growing research programs more broadly defined communication research.” [25] From this point in time communication studies began to gain recognition in schools worldwide.

Germany

Communication studies in Germany has a rich hermeneutic heritage in philology, textual interpretation, and historical studies. The post-World War II era, however, has seen the rise of a number of new paradigms.

Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann pioneered work on the spiral of silence in a tradition that has been widely influential across the world and has proven to be easily compatible with the dominant paradigms in, for instance, the United States.

In the 1970s, Karl Deutsch came to West Germany, and his cybernetics inspired work has been widely influential there as elsewhere.

The work of the Frankfurt School has been a cornerstone of much German work on communication, in addition to Horkheimer, Adorno, and Habermas, figures like Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge has been important in the development of this strand of thought.

An important competing paradigm has been the systems theory developed by Niklas Luhmann and his students.

Finally, from the 1980s and onwards, theorists like Friedrich Kittler have led the development of a 'new German medium theory', aligned partly with the Canadian medium theory of Innis and McLuhan and partly with post-structuralism.

See also

References

- Jefferson D. Pooley, “The New History of Mass Communication Research,” in History of Media and Communication Research: Contested Memories, edited with David Park (New York: Peter Lang, 2008)

- Herbert A. Wichelns, "The Literary Criticism of Oratory," in Studies in Rhetoric and Public Speaking in Honor of James Albert Winans (New York: The Century Co., 1925), 181–216.

- Martin J. Medhurst, "The Academic Study of Public Address: A Tradition in Transition," in Landmark Essays in American Public Address, ed. Martin J. Medhurst (Hermagoras Press 1993), p. xv.

- Martin J. Medhurst, "The Academic Study of Public Address: A Tradition in Transition," in Landmark Essays in American Public Address, ed. Martin J. Medhurst (Hermagoras Press 1993), p. xix.

- "Home". curry.edu.

- Rogers, E. (2001). The department of communication at Michigan State University as a seed institution for communication course. Communication Studies, 52, 234–248.

- Peter Simonson and John Durham Peters, "Communication and Media Studies, History to 1968," in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Wolfgang Donsbach, Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Simonson, Peter, and John Durham Peters. "Communication and Media Studies, History to 1968." In International Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Wolfgang Donsbach. Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- William F. Eadie, "Communication as an Academic Field: USA and Canada," in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Wolfgang Donsbach, Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Peter Simonson and John Durham Peters, "Communication and Media Studies, History to 1968," in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Wolfgang Donsbach, Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Paolo Magaudda, "Communication Studies," in Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture, ed. Dale Southernton (n.p.: n.p., 2011), [21].

- Paris: Librairie Hermann & Cie, 1948.

- Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1949. ISBN 0-252-72548-4. Shannon & Weaver's seminal work, which had developed during World War II, originally appeared during 1948 in Bell System Technical Journal 27, 379–423 (July) and 623–656 (October).

- Richard David Ramsey. (1990). The life and work of Jay R. Gould. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 20, 19-24.

- Lisa Mullikin Parcell, "Communication and Media Studies, History Since 1968," in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Wolfgang Donsbach, Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 2008.

- Paul R. Conroy, "On Giving a Good Account of Ourselves," The Antioch Review, Vol. 18, No 4 (Winter 1958)

- Magaudda, "Communication Studies," in Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture, [22].

- Parcell, "Communication and Media Studies," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Parcell, "Communication and Media Studies," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Simonson and Peters, "Communication and Media Studies," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Eadie, "Communication as an Academic," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Eadie, "Communication as an Academic," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Parcell, "Communication and Media Studies," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Eadie, "Communication as an Academic," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Eadie, "Communication as an Academic," in International Encyclopedia of Communication.