History of Tbilisi

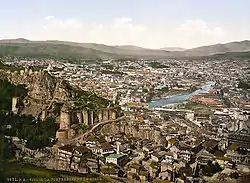

The history of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, dates back to at least the 5th century AD. Since its foundation by the monarch of Georgia's ancient precursor Kingdom of Iberia, Tbilisi has been an important cultural, political and economic center of the Caucasus and served, with intermissions, as the capital of various Georgian kingdoms and republics. Under the Russian rule, from 1801 to 1917 it was called Tiflis and held the seat of the Imperial Viceroy governing both sides of the entire Caucasus.[1]

| History of Georgia საქართველოს ისტორია |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

Tbilisi's proximity to lucrative east–west trade routes often made the city a point of contention between various rival empires, and its location to this day ensures an important transit role.[2] Tbilisi's varied history is reflected in its architecture, which is a mix of medieval, classical, and Soviet structures.

Early history

Legend has it that the present-day territory of Tbilisi was uninhabited and covered by forest as late as 458 AD, the date medieval Georgian chronicles assign to the founding of the city by King Vakhtang I Gorgasali of Iberia (or Kartli, present-day eastern Georgia).

Archaeological studies of the region have however revealed that the territory of Tbilisi was settled by humans as early as the 4th millennium BC. The earliest written accounts of settlement of the location come from the second half of the 4th century AD, when a fortress was built during King Varaz-Bakur's reign (ca. 364). Towards the end of the 4th century the fortress fell into the hands of the Persians, but was recaptured by the kings of Kartli by the middle of the 5th century.

According to one account King Vakhtang Gorgasali (r. 447-502) went hunting in the heavily wooded region with a falcon. The king's falcon caught a pheasant, but both birds fell into a nearby hot spring and died. King Vakhtang was so impressed with the discovery that he decided to build a city on this location. The name Tbilisi derives from the Old Georgian word "Tpili", meaning warm. The name Tbili or Tbilisi ("warm location") therefore was given to the city because of the area's numerous sulfuric hot springs, which are still heavily exploited, notably for public baths, in the Abanotubani district. This mythical foundation account is still popular, but archaeological evidence shows that Vakhtang revived, or rebuilt parts of the city (such as Abanotubani, or the Metekhi palace, where his statue now stands) but did not found it.

Capital of Iberia

King Dachi (beginning of the 6th century), the son and successor of Vakhtang Gorgasali, is said to have moved the capital of Iberia from Mtskheta to Tbilisi to obey the will left by his father. During his reign, Dachi also finished the construction of the fortress wall that lined the city's new boundaries. Beginning from the 6th century, Tbilisi started to grow at a steady pace due to the region's favorable location, which placed the city along important trade and travel routes between Europe and Asia.

However, this location was also strategic from the political point of view, and most major regional powers would struggle during the next centuries for its control. In the 6th century, Persia and the Byzantine Empire were the main contenders for such hegemony over the Caucasus. In the second half of the 6th century, Tbilisi mostly remained under Sassanid (Persian) control, and the kingdom of Iberia was abolished around 580. In 627, Tbilisi was sacked by the allied Byzantine and Khazar armies.

Emirate of Tbilisi

Around 737, Arab armies entered the town under Marwan II Ibn-Muhammad. The Arab conquerors established the Emirate of Tbilisi. Arab rule brought a certain order to the region and introduced a more formal and modernized judicial system into Georgia, while Tbilisi prospered from the trade with the whole Middle East.[3][4] The Arab rule heavily influenced the cultural development of the city. Few Georgians converted to Islam during this time, but Tbilisi became a mainly Muslim city.

In 764, Tbilisi was once again sacked by the Khazars, while still under Arab control. The emirate became an influential local state, and repeatedly tried to gain independence from the caliphate. In 853, the armies of Arab leader Bugha al-Kabir ("Bugha the Turk" in Georgian sources) invaded Tbilisi in order to bring the emirate back under the control of the Abbasid Caliphate. Arab rule in Tbilisi continued until the second half of the 11th century; military attempts by the new Kingdom of Georgia to capture the city were long unsuccessful. The emirate, however, shrank in size, the emirs held less and less power, and the "council of elders" (a local merchant oligarchy) often assumed power in the city.[5] In 1068, the city was once again sacked, only this time by the Seljuk Turks under Sultan Alp Arslan.

Georgian reconquest and Renaissance

In 1122, after heavy fighting with the Seljuks that involved at least 60,000 Georgians and up to 300,000 Turks, the troops of the King of Georgia David the Builder stormed Tbilisi. After the battles for Tbilisi concluded with David's victory, he moved his residence from Kutaisi (Western Georgia) to Tbilisi, making it the capital of a unified Georgian State and thus inaugurating the Georgian Golden Age.[6] From 12–13th centuries, Tbilisi became a dominant regional power with a thriving economy (with well-developed trade and skilled labour) and a well-established social system/structure. By the end of the 12th century, the population of Tbilisi had reached 100,000. The city also became an important literary and a cultural center not only for Georgia but for the Eastern Orthodox world of the time. During Queen Tamar's reign, Shota Rustaveli worked in Tbilisi while writing his legendary epic poem, The Knight in the Panther's Skin. This period is often referred to as the Georgian Golden Age[7] or the Georgian Renaissance[8]

Mongol domination and the following period of instability

Tbilisi's Golden Age did not last for more than a century. In 1236, after suffering crushing defeats to the Mongols, Georgia came under Mongol domination. The nation itself maintained a form of semi-independence and did not lose its statehood, but Tbilisi was strongly influenced by the Mongols for the next century both politically and culturally. In the 1320s, the Mongols were forcefully expelled from Georgia and Tbilisi became the capital of an independent Georgian state once again. An outbreak of the plague struck the city in 1366.

From the late 14th until the end of the 18th century, Tbilisi came under the rule of various foreign invaders once again and on several occasions was completely burnt to the ground. In 1386, Tbilisi was invaded by the armies of Tamerlane (Timur). In 1444, the city was invaded and destroyed by Jahan Shah (the Shah of the town of Tabriz in Persia). From 1477 to 1478 the city was held by the Ak Koyunlu tribesmen of Uzun Hassan.

Tbilisi under Iranian control

As early as the 1510s, Tbilisi, Kartli and Kakheti, were made vassal territories of Safavid Iran.[9] In 1522, Tbilisi was garrisoned for the first time by a large Safavid force.[10][11] Following the death of king (shah) Ismail I (r. 1501-1524), king David X of Kartli expelled the Iranians. During this period, many parts of Tbilisi were reconstructed and rebuilt. The four campaigns of king Tahmasp I (r. 1524-1576) resulted in the reoccupation of Kartli and Kakheti, and a Safavid force was permanently stationed in Tbilisi from 1551 onwards.[10][12] With the 1555 Treaty of Amasya, and more firmly from 1614 to 1747, with brief intermissions, Tbilisi was an important city under Iranian rule, and it functioned as a seat of the Iranian vassal kings of Kartli whom the shah conferred with the title of vali. A wall was built around the city in 1675 by Shah Suleiman I.[13] Under the later rules of Teimuraz II and Erekle II, Tbilisi became a vibrant political and cultural center free of foreign rule, but the city was captured and devastated in 1795 by the Iranian Qajar ruler Agha Mohammad Khan, who sought to re-establish Iran's traditional suzerainty over the region.[14][15][16]

At this point, believing that his Georgian territories of Kartli-Kakheti could not hold up against Iran and its resubjugation alone, Erekle sought the help of Russia, which led to a more complete loss of independence than had been the case in the past centuries, but also to the progressive transformation of Tbilisi into a European city.

Tbilisi under Russian control

In 1801, after the Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti of which Tbilisi was the capital was annexed by the Russian Empire, Iran officially lost control over the city and the wider Georgian lands it had been ruling for centuries.[17] Under Russian rule, the city subsequently became the center of the Tbilisi Governorate (Gubernia). From the beginning of the 19th century Tbilisi started to grow economically and politically. New buildings, mainly of European style, were erected throughout the town. New roads and railroads were built to connect Tbilisi to other important cities in Russia and other parts of Transcaucasia such as Batumi, Poti, Baku, and Yerevan. By the 1850s Tbilisi once again emerged as a major trade and a cultural center. The likes of Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, Mirza Fatali Akhundzade, Iakob Gogebashvili, Alexander Griboedov and many other statesmen, poets, and artists all found their home in Tbilisi. The city was visited on numerous occasions by and was the object of affection of Alexander Pushkin, Leo Tolstoy, Mikhail Lermontov, the Romanov Family and others. The main new artery built under Russian administration was Golovin Avenue (present-day Rustaveli Avenue), on which the Viceroys of the Caucasus established their residence.

Throughout the century, the political, economic and cultural role of Tbilisi with its ethnic, confessional and cultural diversity was significant not only for Georgia but for the whole Caucasus. Hence, Tbilisi took on a different look. It acquired different architectural monuments and the attributes of an international city, as well as its own urban folklore and language, and the specific Tbilisuri (literally, belonging to Tbilisi) culture.

Tatar bazaar and Metekhi palace

Tatar bazaar and Metekhi palace.jpg.webp) Military Cathedral (site of the Parliament building)

Military Cathedral (site of the Parliament building)

Independence: 1918–1921

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the city served as a location of the Transcaucasus interim government which established, in the spring of 1918, the short-lived independent Transcaucasian Federation with the capital in Tbilisi. It was here, in the former Caucasus Vice royal Palace, where the independence of three Transcaucasian nations – Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan – was declared on 26 to 28 May 1918. Since then, Tbilisi functioned as the capital of the Democratic Republic of Georgia until 25 February 1921. From 1918 to 1919 the city was also a home to the German and British military headquarters consecutively.

Under the national government, Tbilisi turned into the first Caucasian University City after the Tbilisi State University was founded in 1918, a long-time dream of the Georgians banned by the Imperial Russian authorities for several decades. On 25 February 1921, the Bolshevist Russian 11th Red Army entered Tbilisi after bitter fighting at the outskirts of the city and declared Soviet rule.

Tbilisi during the Soviet period

In 1921, the Red Army invaded the Democratic Republic of Georgia from Russia, and a Bolshevik regime was installed in Tbilisi. Between 1922 and 1936, Tbilisi was the seat of the Transcaucasian SFSR, which regrouped the three Caucasian republics. After its dissolution, Tbilisi remained the capital city of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic until 1991. In 1936, the official Russian name of the city was changed from Tiflis to Tbilisi, which led to a progressive change of name for the city in most foreign languages.

During Soviet rule, Tbilisi's population grew significantly, the city became more industrialized and came to be one of the most important political, social, and cultural centers of the Soviet Union along with Moscow, Kiev, and Leningrad. Stalinist buildings such as the current Parliament of Georgia were built on the main avenues, but most ancient neighborhoods retained their character. Many religious buildings were destroyed during anti-religious campaigns, such as the Vank Cathedral. With the expansion of the city came new places for culture and entertainment, on the model of other Soviet metropolises: Vake Park was inaugurated in 1946, the Sports Palace in 1961. New standardized residential areas (typical microdistricts) were built from the 1960s: Gldani, Varketili, etc. To link them all with the old city center, a Metro system was developed, which opened in phases from 1966.

In the 1970s and the 1980s the old part of the city was considerably reconstructed. Shota Kavlashvili, the architect who planned the reconstruction, wanted to make the center look like in the 19th century. The reconstruction started from the side of Baratashvili Avenue, where some residential buildings were demolished to uncover the 18th century city wall.[18]

Tbilisi witnessed mass anti-Soviet demonstrations in 1956 (in protest against the anti-Stalin policies of Nikita Khrushchev), 1978 (in defense of the Georgian language) and 1989 (the April 9 tragedy). Both 1956 and 1989 demonstrations were repressed in a bloody way by the authorities, leading to dozens of deaths.

After the break-up of the Soviet Union

.jpg.webp)

Since the break-up of the Soviet Union, Tbilisi has experienced periods of significant instability and turmoil. After a brief civil war which the city endured for two weeks from December 1991 – January 1992 (when pro-Gamsakhurdia and Opposition forces clashed with each other), Tbilisi became the scene of frequent armed confrontations between various mafia clans and illegal business entrepreneurs. Even during the Edvard Shevardnadze era (1993–2003), crime and corruption became rampant at most levels of society. Many segments of society became impoverished due to a lack of employment which was caused by the crumbling economy. Average citizens of Tbilisi started to become increasingly disillusioned with the existing quality of life in the city (and in the nation in general). Mass protests took place in November 2003 after falsified parliamentary elections forced more than 100,000 people into the streets and concluded with the Rose Revolution. Since 2003, Tbilisi has experienced considerably more stability, decreasing crime rates, improving economy, and a booming tourist industry similar to (if not more than) what the city experienced during the Soviet times.

Historical demographic data

As a multicultural city, Tbilisi is home to more than 100 ethnic groups. Around 89% of the population consists of ethnic Georgians, with significant populations of other ethnic groups such as Armenians, Russians, and Azeris. Along with the above-mentioned groups, Tbilisi is home to other ethnic groups including Ossetians, Abkhazians, Ukrainians, Greeks, Germans, Jews, Estonians, Kurds (yazidi and Muslim), Assyrians, and others.

More than 95% of the residents of Tbilisi practice forms of Christianity (the most predominant of which is the Georgian Orthodox Church). The Russian Orthodox Church, which is in Full communion with the Georgian, and the Armenian Apostolic Church have significant following within the city as well. A large minority of the population (around 4%) practices Islam (mainly Shia Islam). About 2% of Tbilisi's population practices Judaism, there is also Roman Catholic church and Yazidism (Sultan Ezid Temple).

Tbilisi has been historically known for religious tolerance. This is especially evident in the city's Old Town, where a mosque, synagogue, and Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches can be found less than 500 metres (1,600 ft) from each other.

References

- David Marshall Lang (1958), The last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, 1658-1832, pp. 227-230. NY: Columbia University Press.

- David Marshall Lang (1958), The last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, 1658-1832, pp. 227-230. NY: Columbia University Press.

- Ronald Grigor Suny (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Barbara A. West (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Suny1994, p. 35

- (in Georgian) Javakhishvili, Ivane (1982), k'art'veli eris istoria (The History of the Georgian Nation), vol. 2, pp. 184-187. Tbilisi State University Press.

- "The Golden Age of Georgia". Dictionary of Georgian National Biography. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- "The Golden Age of Georgia". Dictionary of Georgian National Biography. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Rayfield 2013, pp. 164, 166.

- Hitchins 2001, pp. 464–470.

- Rayfield 2013, p. 166.

- Floor 2008, pp. 295–296.

- Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires. London. p. 211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kazemzadeh 1991, pp. 328–330.

- Suny, pp. 58–59

- Relations between Tehran and Moscow, 1797–2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (10 April 2013). Russia and Britain in Persia: Imperial Ambitions in Qajar Iran. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857721730. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Бабенко, Виталий (October 1983). …внутри драгоценного круга. Vokrug sveta (in Russian). 1983 (10 (2517)). Retrieved 19 August 2012.

Sources

- Floor, Willem M. (2008). Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration, by Mirza Naqi Nasiri. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. pp. 1–324. ISBN 978-1933823232.

- Hitchins, Keith (2001). "GEORGIA ii. History of Iranian-Georgian Relations". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 4. pp. 464–470.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Peter, Avery; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780230702.

- Georgian State (Soviet) Encyclopedia. 1983. Book 4. pp. 595–604.

- Minorsky, V., Tiflis in Encyclopaedia of Islam.

Further reading

- Jersild, Austin, and Neli Melkadze. "The dilemmas of enlightenment in the eastern borderlands: The theater and library in Tbilisi." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 3.1 (2002): 27-49 online.

- Lussac, Samuel. "The Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad and its geopolitical implications for the South Caucasus." Caucasian Review of International Affairs 2.4 (2008): 212-224. online

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 628. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780230702.

- Salukvadze, Joseph; Golubchikov, Oleg (March 2016). "City as a geopolitics: Tbilisi, Georgia — A globalizing metropolis in a turbulent region". Cities. 52: 39–54. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.013.