History of Nigeria before 1500

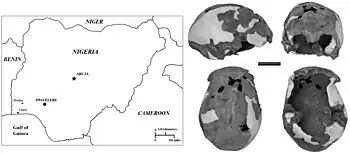

The history of Nigeria before 1500 has been divided into its prehistory, Iron Age, and flourishing of its kingdoms and states. Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene).[1] Middle Stone Age West Africans likely dwelled continuously in West Africa between MIS 4 and MIS 2,[2] and Iwo Eleru people persisted at Iwo Eleru as late as 13,000 BP.[3] West African hunter-gatherers occupied western Central Africa (e.g., Shum Laka) earlier than 32,000 BP,[4] dwelled throughout coastal West Africa by 12,000 BP,[5] and migrated northward between 12,000 BP and 8000 BP as far as Mali, Burkina Faso,[5] and Mauritania.[6] The Dufuna canoe, a dugout canoe found in northern Nigeria has been dated to around 6556-6388 BCE and 6164-6005 BCE,[7] making it the oldest known boat in Africa and the second oldest worldwide.[7][8]

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||

| History of Nigeria | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||

| By state | ||||||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Following migration from the Central Sahara to Nigeria, Nok people settled in the region of Nok in 1500 BCE, and Nok culture continued to persist until 1 BCE.[9] Later, the emergence and flourishing of kingdoms and states occurred, which included the Igbo Kingdom of Nri, the Benin Kingdom, the Yoruba city-states as well as the Kingdom of Ife, Igala Kingdom, the Hausa states, and Nupe. Numerous small states to the west and south of Lake Chad were absorbed or displaced in the course of the expansion of Kanem, which was centered to the northeast of Lake Chad. Bornu, initially the western province of Kanem, became independent in the late 14th century CE.

Prehistory

Early Stone Age

Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene).[1]

Middle Stone Age

Middle Stone Age West Africans likely dwelled continuously in West Africa between MIS 4 and MIS 2, and likely were not present in West Africa before MIS 5.[2] Amid MIS 5, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have migrated across the West Sudanian savanna and continued to reside in the region (e.g., West Sudanian savanna, West African Sahel).[2] In the Late Pleistocene, Middle Stone Age West Africans began to dwell along parts of the forest and coastal region of West Africa (e.g., Tiemassas, Senegal).[2] More specifically, by at least 61,000 BP, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have begun to migrate south of the West Sudanian savanna, and, by at least 25,000 BP, may have begun to dwell near the coast of West Africa.[2] Amid aridification in MIS 5 and regional change of climate in MIS 4, in the Sahara and the Sahel, Aterians may have migrated southward into West Africa (e.g., Baie du Levrier, Mauritania; Tiemassas, Senegal; Lower Senegal River Valley).[2] Iwo Eleru people persisted at Iwo Eleru, in Nigeria, as late as 13,000 BP.[3]

Later Stone Age

Earlier than 32,000 BP,[4] or by 30,000 BP,[10][11] Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers were dwelling in the forests of western Central Africa[11][10] (e.g., earlier than 32,000 BP at de Maret in Shum Laka,[4] 12,000 BP at Mbi Crater).[11] An excessively dry Ogolian period occurred, spanning from 20,000 BP to 12,000 BP.[4] By 15,000 BP, the number of settlements made by Middle Stone Age West Africans decreased as there was an increase in humid conditions, expansion of the West African forest, and increase in the number of settlements made by Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers.[10] Macrolith-using late Middle Stone Age peoples (e.g., the possibly archaic human admixed[12] or late-persisting early modern human[3][13] Iwo Eleru fossils of the late Middle Stone Age), who dwelled in Central Africa, to western Central Africa, to West Africa, were displaced by microlith-using Late Stone Age Africans (e.g., non-archaic human admixed Late Stone Age Shum Laka fossils dated between 7000 BP and 3000 BP) as they migrated from Central Africa, to western Central Africa, into West Africa.[12] Between 16,000 BP and 12,000 BP, Late Stone Age West Africans began dwelling in the eastern and central forested regions (e.g., Ghana, Ivory Coast, Nigeria;[10] between 18,000 BP and 13,000 BP at Temet West and Asokrochona in the southern region of Ghana, 13,050 ± 230 BP at Bingerville in the southern region of Ivory Coast, 11,200 ± 200 BP at Iwo Eleru in Nigeria)[11] of West Africa.[10] After having persisted as late as 1000 BP,[5] or some period of time after 1500 CE,[14] remaining West African hunter-gatherers, many of whom dwelt in the forest-savanna region, were ultimately acculturated and admixed into the larger groups of West African agriculturalists, akin to the migratory Bantu-speaking agriculturalists and their encounters with Central African hunter-gatherers.[5] In the northeastern region of Nigeria, Jalaa, a language isolate, may be a descendant language from the original set(s) of languages spoken by West African hunter-gatherers.[5]

Iron Age

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in West Africa, Central Africa, and East Africa; consequently, as these origin centers are located within inner Africa, these archaeometallurgical developments are thus native African technologies.[15] Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[16][17] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[17][18] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[19][20] More recently, Bandama and Babalola (2023) have indicated that iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria, 2136 BCE – 1921 BCE at Obui, in Central Africa Republic, 1895 BCE – 1370 BCE at Tchire Ouma 147, in Niger, and 1297 BCE – 1051 BCE at Dekpassanware, in Togo.[15]

Nok culture

The Nok peoples and the Gajiganna peoples may have migrated from the Central Sahara, along with pearl millet and pottery, diverged prior to arriving in the northern region of Nigeria, and thus, settled in their respective locations in the region of Gajiganna and Nok.[9] Nok culture may have emerged in 1500 cal BCE and continued to persist until 1 cal BCE.[9] Nok people may have developed terracotta sculptures, through large-scale economic production,[21] as part of a complex funerary culture[22] that may have included practices such as feasting.[9] The earliest Nok terracotta sculptures may have developed in 900 BCE.[9] Some Nok terracotta sculptures portray figures wielding slingshots, as well as bows and arrows, which may be indicative of Nok people engaging in the hunting, or trapping, of undomesticated animals.[23] A Nok sculpture portrays two individuals, along with their goods, in a dugout canoe.[23] Both of the anthropomorphic figures in the watercraft are paddling.[24] The Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe may indicate that Nok people used dugout canoes to transport cargo, along tributaries (e.g., Gurara River) of the Niger River, and exchanged them in a regional trade network.[24] The Nok terracotta depiction of a figure with a seashell on its head may indicate that the span of these riverine trade routes may have extended to the Atlantic coast.[24] In the maritime history of Africa, there is the earlier Dufuna canoe, which was constructed approximately 8000 years ago in the northern region of Nigeria; as the second earliest form of water vessel known in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe was created in the central region of Nigeria during the first millennium BCE.[24] Latter artistic traditions of West Africa – Bura of Niger (3rd century CE – 10th century CE), Koma of Ghana (7th century CE – 15th century CE), Igbo-Ukwu of Nigeria (9th century CE – 10th century CE), Jenne-Jeno of Mali (11th century CE – 12th century CE), and Ile Ife of Nigeria (11th century CE – 15th century CE) – may have been shaped by the earlier West African clay terracotta tradition of the Nok culture.[25] Mountaintops are where the majority of Nok settlement sites are found.[26] At the settlement site of Kochio, the edge of a cellar of a settlement wall was chiseled from a granite foundation.[26] Additionally, a megalithic stone fence was constructed around the enclosed settlement site of Kochio.[26] Also, a circular stone foundation of a hut was discovered in Puntun Dutse.[27] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[19][20] As each share cultural and artistic similarity with the Nok culture found in Nok, Sokoto, and Katsina, the Niger-Congo-speaking Yoruba, Jukun, or Dakakari peoples may be descendants of the Nok peoples.[28] Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba Ife Empire and the Bini kingdom of Benin may also be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[29]

Kingdoms and states

Kingdom of Nri

The Nri Kingdom in the Awka area was founded in about 900 AD in north central Igboland, and is considered the oldest kingdom in Nigeria. The Nsukka-Awka-Orlu axis is said to be the oldest area of Igbo settlement and therefore, homeland of the Igbo people. It was a center of spirituality, learning, and commerce. They were agents of peace and harmony whose influence stretched beyond Igboland. The Nri people's influence in neighboring lands was especially in southern Igalaland and the Benin Kingdom in the 12th to 15th centuries. As great travelers, they were also business people involved in the long distant trans-Saharan trade. The development and sophistication of this civilization is evident in the bronze castings found in Igbo Ukwu, an area of Nri influence. The Benin Kingdom became a threat in the 15th century under Oba Ewuare. Since they were against slavery, their power took a downturn when the slave trade was at its peak in the 18th century. The Benin and Igala slave raiding empires became the main influence in their relationship with western and northern Igbos, their former main areas of influence and operation. Upper northwest Cross River Igbo groups like the Aro Confederacy and Ohafia peoples, as well as the Awka and Umunoha people used oracular activities and other trading opportunities after Nri's decline in the 18th century to become the major influences in Igboland and all adjacent areas.

Edo kingdom

During the 15th century, Benin was the first to receive foreign traders.

Edoland established a community in the Yoruba-speaking area east of Ubini before becoming a dependency of Benin Kingdom at the beginning of the 14th century. By the 15th century it became an independent trading power, blocking Ife's access to the coastal ports as Oyo had cut off the mother city from the savanna. Political and religious authority resided in the oba (king) who according to tradition was descended from Oduduwa the first ooni of ife. Benin spread over a large area enclosed by concentric rings of earthworks. By the late 15th century Edo Kingdom was in contact with Portugal who traded resources (palm oil, cotton etc.). At its apogee in the 16th and 17th centuries, Edo encompassed parts of southeastern Yorubaland and the western parts of the present Delta State.

Yoruba and Benin kingdoms

Historically the Yoruba have been the dominant group on the west bank of the Niger. They were the product of periodic waves of migrants.[30] The Yoruba were organized in patrilineal groups that occupied village communities and subsisted on agriculture. From about the 8th century, adjacent village compounds, called Ilé, coalesced into numerous territorial city-states in which clan loyalties became subordinate to dynastic chieftains. The earliest known of these city states formed at Ilé-Ifẹ̀ and Ijebuland. Urbanization was accompanied by high levels of artistic achievement, particularly in terracotta and ivory sculpture and in the sophisticated metal casting produced at Ilé-Ifẹ̀. The Yoruba placated a luxuriant pantheon headed by an impersonal deity, Olorun, and included lesser deities who performed various tasks. Oduduwa was regarded as the creator of the earth and the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to myth, Oduduwa founded Ife and dispatched his sons to establish other cities, where they reigned as priest-kings. Ile Ife was the center of as many as 400 religious cults whose traditions were manipulated to political advantage by the Ooni of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ (king).

The oni was chosen on a rotating basis, from a branch of the ruling dynasty. Once a member was selected, they were secluded from the rest. Below the oni, in the state there were: palace officials, town chiefs, and rulers of outlying dependencies. The Ife model of government was adapted at Oyo. Eventually, Oyo turned into a constitutional monarchy, but this was not the actual government. Unlike the other Yoruba subgroups, the Oyo had cavalry forces. This helped develop trading further north.[30]

Northern kingdoms of the Sahel

Trade was the key to the emergence of organized communities in the savanna portions of Nigeria. Prehistoric inhabitants adjusting to the encroaching desert were widely scattered by the third millennium BC, when the desiccation of the Sahara began. Trans-Saharan trade routes linked the western Sudan with the Mediterranean since the time of Carthage and with the Upper Nile from a much earlier date, establishing avenues of communication and cultural influence that remained open until the end of the 19th century. By these same routes, Islam made its way south into West Africa after the 9th century AD.[30]

By then a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched across the western and central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and Kanem, which were not within the boundaries of modern Nigeria but indirectly influenced the history of the Nigerian savanna. Ghana declined in the 11th century but was succeeded by Mali Empire which consolidated much of the western Sudan in the 13th century. Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and the western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sunni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Jenne in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askiya Mohammad Ture made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili, the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship, to Gao.[31] Although these western empires had little political influence on the Nigerian savanna before 1500, they had a strong cultural and economic impact that became more pronounced in the 16th century, especially because these states became associated with the spread of Islam and trade. Throughout the 16th century much of northern Nigeria paid homage to Songhai in the west or to Bornu, a rival empire, in the east.

Kanem-Bornu Empire

Bornu's history is closely associated with Kanem, which had achieved imperial status in the Lake Chad basin by the 13th century. Kanem expanded westward to include the area that became Bornu. The mai (king) of Kanem and his court accepted Islam in the 11th century, as the western empires also had done. Islam was used to reinforce the political and social structures of the state although many established customs were maintained. Women, for example, continued to exercise considerable political influence.

The mai employed his mounted bodyguard and an inchoate army of nobles to extend Kanem's authority into Bornu. By tradition the territory was conferred on the heir to the throne to govern during his apprenticeship. In the 14th century, however, dynastic conflict forced the ruling group and its followers to relocate in Bornu, where as a result the Kanuri emerged as an ethnic group in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The civil war that disrupted Kanem in the second half of the 14th century resulted in the independence of Bornu.

Bornu's prosperity depended on the trans-Sudanic slave trade and the desert trade in salt and livestock. The need to protect its commercial interests compelled Bornu to intervene in Kanem, which continued to be a theater of war throughout the 15th and into the 16th centuries. Despite its relative political weakness in this period, Bornu's court and mosques under the patronage of a line of scholarly kings earned fame as centers of Islamic culture and learning.

Hausa states

By the 11th century some Hausa states - such as Kano, Katsina, and Gobir - had developed into walled towns engaging in trade, servicing caravans, and the manufacture of various goods. Until the 15th century these small states were on the periphery of the major Sudanic empires of the era. They were constantly pressured by Songhai to the west and Kanem-Bornu to the east, to which they paid tribute. Armed conflict was usually motivated by economic concerns, as coalitions of Hausa states mounted wars against the Jukun and Nupe in the middle belt to collect slaves or against one another for control of trade.

Islam arrived to Hausaland along the caravan routes. The famous Kano Chronicle records the conversion of Kano's ruling dynasty by clerics from Mali, demonstrating that the imperial influence of Mali extended far to the east. Acceptance of Islam was gradual and was often nominal in the countryside where folk religion continued to exert a strong influence. Nonetheless, Kano and Katsina, with their famous mosques and schools, came to participate fully in the cultural and intellectual life of the Islamic world. The Fulani began to enter the Hausa country in the 13th century, and by the 15th century they were tending cattle, sheep, and goats in Bornu as well. The Fulani came from the Senegal River valley, where their ancestors had developed a method of livestock management based on transhumance. Gradually they moved eastward, first into the centers of the Mali and Songhai empires and eventually into Hausaland and Bornu. Some Fulbe converted to Islam as early as the 11th century and settled among the Hausa, from whom they became ethnically indistinguishable. There they constituted a devoutly religious, educated elite who made themselves indispensable to the Hausa kings as state advisers, Islamic tribunes, and teachers.

References

- Scerri, Eleanor (October 26, 2017). "The Stone Age Archaeology of West Africa" (PDF). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1, 31. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.137. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. S2CID 133758803.

- Niang, Khady; et al. (2020). "The Middle Stone Age occupations of Tiémassas, coastal West Africa, between 62 and 25 thousand years ago". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 34: 102658. Bibcode:2020JArSR..34j2658N. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102658. ISSN 2352-409X. OCLC 8709222767. S2CID 228826414.

- Bergström, Anders; et al. (2021). "Origins of modern human ancestry" (PDF). Nature. 590 (7845): 232. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..229B. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03244-5. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 8911705938. PMID 33568824. S2CID 231883210.

- MacDonald, K.C. (April 2011). "Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faita Facies, Tichitt Tradition". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 46: 49, 51, 54, 56–57, 59–60. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2011.553485. ISSN 0067-270X. OCLC 4839360348. S2CID 161938622.

- MacDonald, Kevin C. (Sep 2, 2003). "Archaeology, language and the peopling of West Africa: a consideration of the evidence". Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. pp. 39–40, 43–44, 48–49. doi:10.4324/9780203202913-11. ISBN 9780203202913. OCLC 815644445. S2CID 163304839.

- Abd-El-Moniem, Hamdi Abbas Ahmed (May 2005). A New Recording Of Mauritanian Rock Art (PDF). University of London. p. 221. OCLC 500051500. S2CID 130112115.

- Breunig, Peter; Neumann, Katharina; Van Neer, Wim (1996). "New research on the Holocene settlement and environment of the Chad Basin in Nigeria". African Archaeological Review. 13 (2): 116–117. doi:10.1007/BF01956304. JSTOR 25130590. S2CID 162196033.

- Richard Trillo (16 June 2008). "Nigeria Part 3:14.5 the north and northeast Maiduguri". The Rough Guide to West Africa. Rough Guides. pp. Unnumbered. ISBN 978-1-4053-8070-6.

- Champion, Louis; et al. (15 December 2022). "A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 32 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1007/s00334-022-00902-0. S2CID 254761854.

- Scerri, Eleanor M. L. (2021). "Continuity of the Middle Stone Age into the Holocene". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 70. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79418-4. OCLC 8878081728. PMC 7801626. PMID 33431997. S2CID 231583475.

- MacDonald, Kevin C. (Sep 2, 2003). "Archaeology, language and the peopling of West Africa: a consideration of the evidence". Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. pp. 39–40, 43–44, 49–50. doi:10.4324/9780203202913-11. ISBN 9780203202913. OCLC 815644445. S2CID 163304839.

- Schlebusch, Carina M.; Jakobsson, Mattias (2018). "Tales of Human Migration, Admixture, and Selection in Africa". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 19: 407. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021759. ISSN 1527-8204. OCLC 7824108813. PMID 29727585. S2CID 19155657.

- Eborka, Kennedy (February 2021). "Migration and Urbanization in Nigeria from Pre-colonial to Post-colonial Eras: A Sociological Overview". Migration and Urbanization in Contemporary Nigeria: Policy Issues and Challenges. University of Lagos Press. p. 6. ISBN 9789785435160. OCLC 986792367.

- Van Beek, Walter E.A.; Banga, Pieteke M. (Mar 11, 2002). "The Dogon and their trees". Bush Base, Forest Farm: Culture, Environment, and Development. Routledge. p. 66. doi:10.4324/9780203036129-10. ISBN 9781134919567. OCLC 252799202. S2CID 126989016.

- Bandama, Foreman; Babalola, Abidemi Babatunde (13 September 2023). "Science, Not Black Magic: Metal and Glass Production in Africa". African Archaeological Review. doi:10.1007/s10437-023-09545-6. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 10004759980. S2CID 261858183.

- Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria,Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6. S2CID 161611760.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9783937248462.

- Champion, Louis; et al. (15 December 2022). "A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 32 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1007/s00334-022-00902-0. S2CID 254761854.

- Ehret, Christopher (2023). "African Firsts in the History of Technology". Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 19. doi:10.2307/j.ctv34kc6ng.5. ISBN 9780691244105. JSTOR j.ctv34kc6ng.5. OCLC 1330712064.

- Sun, Z. J.; et al. (2017). "Instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) of Nok sculptures in I. P. Stanback Museum". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 313: 85–92. doi:10.1007/s10967-017-5297-8. ISSN 0236-5731. OCLC 7062772522. S2CID 98924415.

- Breunig, Peter (2022). "Prehistoric Developments In Nigeria". In Falola, Toyin; Heaton, Matthew M (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Nigerian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 123–124. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190050092.013.5. ISBN 978-0-19-005009-2. OCLC 1267402325. S2CID 249072850.

- Franke, Gabriele; et al. (2020). "Pits, pots and plants at Pangwari: Deciphering the nature of a Nok Culture site". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 55 (2): 129–188. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2020.1757902. ISSN 0067-270X. OCLC 8617747912. S2CID 219470059.

- Männel, Tanja M.; Breunig, Peter (12 Jan 2016). "The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari". Journal of African Archaeology. 14 (3): 321. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10300 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 44295244. OCLC 8512545149. S2CID 164688675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Ramsamy, Edward; Elliott, Carolyn M.; Seybolt, Peter J. (January 5, 2012). "Part I: Prehistory To 1400". Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 8. doi:10.4135/9781452218458. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7. OCLC 809773339. S2CID 158838141.

- Rupp, Nicole; Ameje, James; Breunig, Peter (2005). "New Studies on the Nok Culture of Central Nigeria". Journal of African Archaeology. 3 (2): 287. doi:10.3213/1612-1651-10056. ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 43135381. OCLC 5919406005. S2CID 162190915.

- Breunig, Peter; Rupp, Nicole (2016). "An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture" (PDF). Journal of African Archaeology. 14 (3): 242, 247. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10298 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 44295241. OCLC 8512542846. S2CID 56195865.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Lamp, Frederick John (2011). "Ancient Terracotta Figures from Northern Nigeria". Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin: 55. ISSN 0084-3539. JSTOR 41421509. OCLC 9972665249.

- Shillington (2005), p. 39

- Metz, Helen Chapin (1992). Nigeria : a country study. Washington, D.C. : Federal Research Division, Library of Congress : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 1992. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge 1988

Bibliography

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333599570.