History of Genoa

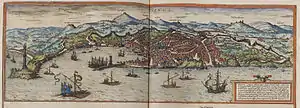

Genoa, Italy, has historically been one of the most important ports on the Mediterranean.

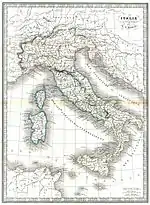

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

Prehistory and antiquity

The Genoa area has been inhabited since the fifth or fourth millennium BC.[1] In ancient times this area was inhabited by Ligures (ancient people after whom Liguria is named). According to excavations carried out in the city between 1898 and 1910, the Ligure population that lived in Genoa maintained trade relations with the Etruscans and the Greeks, since several objects from these populations were found.[2][3] In the fifth century BC the first town, or oppidum, was founded at the top of the hill today called Castello (Castle), which is now inside the medieval old town. The ancient Ligurian city was known as Stalia (Σταλìα), referred to in this way by Artemidorus Ephesius and Pomponius Mela. Stalia had an alliance with Rome through a foedus aequum (equal pact) in the course of the Second Punic War (218-201 BC). The Carthaginians accordingly destroyed it in 209 BC. The town was rebuilt and, after the Carthaginian Wars ended in 146 BC, it received municipal rights. The original castrum then expanded towards the current areas of Santa Maria di Castello and the San Lorenzo promontory. Trade goods included skins, timber, and honey. Goods were moved to and from Genoa's hinterland, including major cities like Tortona and Piacenza. An amphitheater was also found there among other archaeological remains from the Roman period.

The city's modern name may derive from the Latin word meaning "knee" (genu; plural, genua) but there are other theories. It could derive from the god Janus, because Genoa, like him, has two faces: a face that looks at the sea and another turned to the mountains. Or it could come from the Latin word ianua, also related to the name of the God Janus, and meaning "door" or "passage." Besides that, it may refer to its geographical position at the centre of the Ligurian coastal arch, thus akin to the name of Geneva.[4] The Latin name, oppidum Genua, is recorded by Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. 3.48) as part of the Augustean Regio IX Liguria.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Ostrogoths occupied Genoa. After the Gothic War, the Byzantines made it the seat of their vicar. When the Lombards invaded Italy in 568, Bishop Honoratus of Milan fled and held his seat in Genoa.[5] Pope Gregory the Great was closely connected to these bishops in exile, for example involving himself in the election of Deusdedit.[6] The Lombards, under King Rothari, finally captured Genoa and other Ligurian cities in about 643.[7] In 725 the mortal remains of Augustine of Hippo arrived in Genoa. In 773 the Lombard Kingdom was annexed by the Frankish Empire; the first Carolingian count of Genoa was Ademarus, who was given the title praefectus civitatis Genuensis. Ademarus died in Corsica while fighting against the Saracens. In this period the Roman walls, destroyed by the Lombards, were rebuilt and extended.

For the following several centuries, Genoa was little more than a small centre, slowly building its merchant fleet, which was to become the leading commercial carrier of the Mediterranean Sea. The town was thoroughly sacked and burned in 934–35 by a Fatimid fleet under Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Tamimi and possibly even abandoned for a few years.[8]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Before 1100, Genoa emerged as an independent city-state, one of a number of Italian city-states established during this period. Nominally, the Holy Roman Emperor was sovereign and the Bishop of Genoa was head of state; however, actual power was wielded by a number of consuls annually elected by popular assembly. Genoa was one of the states known as Repubbliche Marinare along with Venice, Pisa, and Amalfi. Trade, shipbuilding, and banking helped support one of the largest and most powerful navies in the Mediterranean. There is an old saying that says: Genuensis ergo mercator, or "A Genoese therefore a merchant" but the Genoese were skilled sailors and ferocious warriors in addition (see also the Genoese crossbowmen).

In 1098, it is said the ashes of John the Baptist, now the patron saint of the city, arrived in Genoa. The Adorno, Campofregoso, and other smaller merchant families all fought for power in this republic, as the power of the consuls allowed each family faction to gain wealth and power in the city. The Republic of Genoa extended over modern Liguria, Piedmont, Sardinia (see also Pisan-Genoese expeditions to Sardinia), Corsica, and Nice, and had practically complete control of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Through Genoese participation in the Crusades, colonies were established in the Middle East, the Aegean Sea, Sicily, and Northern Africa. The cronista, or chronicler, of the Genoese vicissitudes was Caffaro di Rustico da Caschifellone and the hero and military leader was Guglielmo Embriaco called Testadimaglio meaning "mallet head" (see also Siege of Jerusalem (1099)). Genoese Crusaders brought home a green glass goblet from the Levant (see also Holy Chalice), which the Genoese have long regarded as the Holy Grail. In his Golden Legend, the Archbishop of Genoa, Jacobus de Voragine relates the history of the Holy Grail. Not all of Genoa's merchandise was so innocuous, however, as medieval Genoa became a major player in the slave trade.[9]

The Genoese have a claim to the creation of the rough denim cloth then called "Blue Jean", from which derives the modern name of jeans, used by sailors for work and to cover and protect their goods on the docks from the weather. During the Republic of Genoa, Genoese merchants and sailors exported this cloth throughout Europe. The production of Genoese lace was also notable.

The collapse of the Crusader States was offset by Genoa's alliance with the Byzantine Empire. As Venice's relations with the Byzantines were temporarily disrupted by the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath, Genoa was able to improve its position, taking advantage of the opportunity to expand into the Black Sea and Crimea. Internal feuds between the powerful families, the Grimaldi and Fieschi, the Doria, Spinola and others, caused much disruption, but in general the republic was run much as a business affair.

In 1218–1220 Genoa was served by the Guelph podestà Rambertino Buvalelli, who probably introduced Occitan literature, which was soon to boast such troubadours as Jacme Grils, Lanfranc Cigala and Bonifaci Calvo, to the city. During this time, 1218–1219, a Genoese fleet under Simone Doria with the famous Genoese pirate Alamanno da Costa participated in the Siege of Damietta; about this period we must also remember the Genoese privateer and pirate, Henry, Count of Malta. The alliance between Byzantines and Genoese suffered after the Battle of Settepozzi, admirably described in the Annales ianuenses.

Genoa's political zenith came with its victory over the Republic of Pisa at the naval Battle of Meloria in 1284, and with a temporary victory over its rival, Venice, at the naval Battle of Curzola in 1298 during the Venetian-Genoese Wars. The Genoese navy was on a par with the Venetian navy and both cities had the power to rule the sea. Notable conflicts between Byzantines and Genoese were the Genoese occupation of Rhodes and the Byzantine-Genoese War.

However, this period of prosperity did not last. The Black Death is said to have been imported into Europe in 1347 from the Genoese trading post at Caffa in Crimea on the Black Sea. Following the economic and population collapse that resulted, Genoa adopted the Venetian model of government and was presided over by the Doge of Genoa. The wars with Venice continued, and the War of Chioggia (1378–1381) – during which Genoa almost managed to decisively subdue Venice – ended with Venice's recovery of dominance in the Adriatic. In 1390, Genoa initiated the Barbary Crusade, with help from the French, and laid siege to Mahdia, the Fatimid capital of Ifriqiya.

Though not well-studied, Genoa in the 15th century seems to have been tumultuous. The city had a strong tradition of trading goods from the Levant and its financial expertise was recognised all over Europe. After a period of French domination from 1394 to 1409, Genoa came under the rule of the Visconti of Milan (see also Battle of Ponza). Genoa lost Sardinia to Aragon, Corsica to internal revolt, and its Middle Eastern, Eastern European, and Asia Minor colonies to the Ottoman Empire.

In the 15th century two of the earliest banks in the world were founded in Genoa: the Bank of Saint George, founded in 1407, which was the oldest chartered bank in the world at its closure in 1805 and the Banca Carige, founded in 1483 as a mount of piety, which still exists.

Genoa was able to stabilise its position as it moved into the 16th century, particularly as a result of the efforts of Doge Andrea Doria, who granted a new constitution in 1528 that made Genoa a satellite of the Spanish Empire (Siege of Coron 1532/34, Battle of Preveza 1538, Battle of Girolata 1540, Battle of Lepanto 1571, Relief of Genoa 1625). Some Genoese enjoyed remarkable careers in the service of the Spanish crown: notably the maritime explorers Juan Bautista Pastene and Leon Pancaldo, the general Ambrogio Spinola, the naval captain Giovanni della Croce Bernardotte and Jorge Burgues. In the period of economic recovery which followed, many aristocratic Genoese families, such as the Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini and Serra, amassed tremendous fortunes. According to Felipe Fernandez-Armesto and others, the practices Genoa developed in the Mediterranean (such as chattel slavery) were crucial in the exploration and exploitation of the New World.[10]

The Genoese Pietro Vesconte, Giovanni da Carignano and Battista Beccario (see Genoese map before the discovery of the Americas) were pioneers in cartography. Christopher Columbus himself was a native of Genoa and donated one-tenth of his income from the discovery of the Americas for Spain to the Bank of Saint George in Genoa for the relief of general taxation on food. Columbus was the culmination of a long tradition of Genoese navigators and explorers such as Vandino and Ugolino Vivaldi, Lancelotto Malocello, Luca Tarigo, Antonio de Noli, Antonio Malfante and Antoniotto Usodimare. (It has been suggested that Antoniotto Usodimare and Antonio di Noli may be different names for the same person.) The famous Genoese navigator John Cabot, a contemporary of Columbus, discovered northern parts of North America when sailing under the commission of Henry VII of England.

During its rise and its apogee, Genoa founded colonies in many parts of the world from Crimea to North Africa, from Spain to the Americas, leaving valuable architectural works in many locations, such as the forts of Caffa, Balaklava, Sudak and Tabarka, the Galata Tower in Istanbul, the Lighthouse in Constanța, the Towers in Corsica and Sardinia. The Genoese established commercial bases and colonies around the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, called Gazaria. They established flourishing communities in Constantinople, Cádiz, Lisbon and Gibraltar (see also History of the Genoese in Gibraltar and Levantines); these communities were organised and governed by Maona (see also Chio's Maona and Focea). The story of Cigalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha or Scipione Cicala, member of the aristocratic Genoese family of Cicala, is fascinating: it is said he was caught by the Ottomans in the Battle of Djerba and then he became Kapudan Pasha or Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet, (this adventure story is sung by Fabrizio De André in "Sinàn Capudàn Pascià").

At the time of Genoa's zenith in the 16th century, the city attracted many artists including Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Dyck. The famed architect Galeazzo Alessi (1512–1572) designed many of the city's splendid palazzi, and Bartolomeo Bianco (1590–1657) designed the centrepieces of the University of Genoa. A number of Genoese Baroque and Rococo artists settled elsewhere and a number of local artists became prominent. In the late sixteenth century, Luca Cambiaso, known as the founder of the Genoese School of painting, went on to earn the largest payment then recorded (2,000 ducats) for work for Philip II of Spain in the Escorial palace in Madrid.

In the 17th century, however, Genoa entered a period of crisis. In May 1625, a French-Savoian army invaded the republic but was successfully driven out by the combined Spanish and Genoese armies. In 1656–57, a new outburst of plague killed as many as half of the population.[11] In May 1684, as a punishment for Genoese support for Spain, the city was subjected to a French naval bombardment with some 13,000 cannonballs aimed at the city.[12] Genoa was eventually occupied by Austria in 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession. This episode in the city's history is mainly remembered for the Genoese revolt, precipitated by a legendary boy named Giovan Battista Perasso and nicknamed Balilla who threw a stone at an Austrian official and became a national hero to later generations of Genoese, and Italians in general (see also Siege of Genoa (1746), Siege of Genoa (1747), and Siege of Genoa (1800)). Unable to retain its rule in Corsica, where the rebel Corsican Republic was proclaimed in 1755, Genoa was forced by the well-supported rebellion to sell its claim to Corsica to the French, under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles of 1768.

Modern history

With the shift in world economy and trade routes to the New World and away from the Mediterranean, Genoa's political and economic power began a steady decline. Its military power collapsed during the Raid on Genoa in 1793 and the Battle of Genoa in 1795 where Genoa fought the French fleet and the English. In 1797, under pressure from Napoleon, the Republic of Genoa became a French protectorate called the Ligurian Republic, which was annexed by France in 1805. This fact is mentioned in the first sentence of Tolstoy's War and Peace:

Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Buonapartes.(...) And what do you think of this latest comedy, the coronation at Milan, the comedy of the people of Genoa and Lucca laying their petitions [to be annexed to France] before Monsieur Buonaparte, and Monsieur Buonaparte sitting on a throne and granting the petitions of the nations?" (spoken by a thoroughly anti-Bonapartist Russian aristocrat, soon after the news reached Saint Petersburg).

Although the Genoese revolted against France in 1814 and liberated the city on their own, delegates at the Congress of Vienna sanctioned its incorporation into the Kingdom of Sardinia, thus ending the three century old struggle by the House of Savoy to acquire the city.

The city soon gained a reputation as a hotbed of anti-Savoy republican agitation. Genoa was the centre of an important reform movement that put constant pressure on Piedmont to grant the freedom of the press and more liberal laws. The citizens of the republic would not accept being subjects of an absolute monarchy, wanting to be Italian rather than Piedmontese, though relations with Piedmont improved with the war against Austria. However, after the defeat in the First War of Independence and the armistice of Salasco, the Genoese, fearing the loss of freedom and independence as a consequence of a peace imposed by Austria, rose up and hunted the Piedmontese garrison. After the uprising of Genoa, the troops of the general Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora moved against the city, besieged, bombed and sacked it. With the rise of the Risorgimento, reunification of Italy, movement, the Genoese turned their struggles from Giuseppe Mazzini's vision of a local republic into a struggle for a unified Italy under a liberalised Savoy monarchy. In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi set out from Genoa with over a thousand volunteers to begin the conquest of Southern Italy among them was Nino Bixio. Today a monument is set on the rock at the point where the patriot embarked, in Quarto dei Mille.

In the 19th and the early 20th centuries, Genoa consolidated its role as a major seaport and an important steel and shipbuilding centre. In Genoa in 1853, Giovanni Ansaldo founded Gio. Ansaldo & C. whose shipyards would build some of the most beautiful ships in the world, such as ARA Garibaldi, SS Roma, MS Augustus, SS Rex, SS Andrea Doria, SS Cristoforo Colombo, MS Gripsholm, SS Leonardo da Vinci, SS Michelangelo, and SS SeaBreeze. In 1854, the ferry company Costa Crociere was founded in Genoa and then the Lloyd Italiano maritime insurance company. In 1861 the Registro Italiano Navale Italian register of shipping was created, and in 1879 the Yacht Club Italiano. The owner Raffaele Rubattino in 1881 was among the founders of the ferry company Navigazione Generale Italiana which then become the Italian Line.

In 1884 Rinaldo Piaggio founded Piaggio & C. that produced locomotives and railway carriages and in 1923 began aircraft production. The company as Piaggio Aerospace at present is owned by Mubadala Development Company and is based in Villanova d'Albenga. (After World War II, Enrico Piaggio son of Rinaldo Piaggio, with the engineer Corradino D'Ascanio conceived and realised one of the most common means of transport, the Vespa). In 1870 was founded Banca di Genova which in 1895 changed its name to Credito Italiano and in 1998 became Unicredit. Also in Genoa in 1898 the insurance company called Alleanza Assicurazioni was founded. In 1874 the city was completely connected by railway lines to France and the rest of Italy: Genoa-Turin, Genoa-Ventimiglia, Genoa-Pisa.

In Genoa the following shipyards were established: Cantiere Navale di Sestri Ponente, Cantiere della Foce, Cantiere navale di Riva Trigoso, Cantieri navali di Voltri but also the sugar factory Eridania, the food brands Saiwa, Elah and Icat Food. These technological and industrial developments would have worldwide exposure in 1892 when the city hosted the international exhibition "Esposizione Italo-Americana" and again in 1914 with the Esposizione Internazionale di Marina e di igiene marinara (see the List of world's fairs). The strong industrialisation attracted large masses of workers which is why in 1892 the Italian Socialist Party was founded here by Filippo Turati, Andrea Costa, and Anna Kuliscioff. In 1886 was founded the newspaper Il Secolo XIX and in 1903 the socialist newspaper "Il Lavoro". Palmiro Togliatti, one of the most influential Italian politicians of the 20th century, was born in Genoa in 1893.

In this period many Genoese emigrated to the Americas (see also Italian diaspora). Among the most interesting experiences of this exodus was the creation of the Buenos Aires district called La Boca, now famous for its colorful houses in the Ligurian style, in addition on 3 April 1905 a group of Genoese boys founded the Boca Juniors football club in Buenos Aires. This is why the fans of Boca Juniors are called "Los Xeneizes", which means the Genoese. In addition, Amadeo Giannini, the son of Genoese immigrants in North America, founded the Bank of America. (See also "Italian Peruvians", "Italian Chileans", "Italian Uruguayans").

During World War I the Genoese shipyards were very active, importing vast quantities of materials necessary for the war effort, and between thirty thousand and eighty thousand Genoese left for the battlefront. About this period we have to remember the admiral Raffaele Rossetti, famous for the sinking of the battleship SMS Viribus Unitis. Important urban and architectural works were constructed under Fascism including: Piazza Dante which includes the Piacentini's Tower, Piazza della Vittoria with its Arco della Vittoria, and the Bisagno stream water tunnel. In 1935, the only synagogue built during the fascist period, the Synagogue of Genoa, was inaugurated.

Genoa also gave rise to numerous industries like the steelworks "S.I.A.C." in Cornigliano, the metallurgical company "F.I.T.", the oil refining company "IPLOM SpA", and the energy company ERG. In 1921 Carlo Guzzi, together with Angelo and Giorgio Parodi, founded Moto Guzzi in Genoa. In 1922 the city was the headquarters for the financial and economic conference called the Genoa Conference that was a consequence of the Treaty of Rapallo.

During the fascist period the city of Genoa was united to nineteen municipalities, creating in 1926 what was known as "Greater Genoa", which stretches along the coast for 35 km (22 miles).

In World War II Genoa suffered heavy damage from both naval and aerial bombing raids. After some ineffectual air raids in 1940, in February 1941 the city suffered heavy damage in a naval bombardment carried out by the British Force H (Operation Grog); then, in the autumn of 1942, it became the first city in Italy to experience area bombing, with six such raids between 22 October and 15 November 1942 and a further one on 8 August 1943.[13] Between late 1943 and the end of the war, both the RAF and the USAAF carried out several more bombing raids aimed at the port facilities, factories and marshalling yards of Genoa. Overall, Genoa suffered over fifty air raids, which caused some 2,000 deaths among the population.[14] 11,183 buildings were destroyed or damaged, including 70 churches and 130 historic palaces, and 75% of the port facilities were destroyed.[15]

The exploits during this period of admiral Luigi Durand de la Penne, especially the Raid on Alexandria, are retold in several films, including The Valiant, The Silent Enemy and Human Torpedoes.

After the Armistice of Cassibile, Genoa and the surrounding mountains became a center of the Italian Resistance; between 1943 and 1945, 1,836 Genoese partisans were killed, and 2,250 anti-fascists were deported from the city to concentration camps in Germany.[16] The city was liberated by the partisans a few days before the arrival of the Allies; 150 partisans were killed and 350 wounded during the fighting for the liberation of the city, which resulted in the capture of 14,000 German prisoners under General Günther Meinhold on 27 April 1945.[15][17]

During World War II, many Jewish refugees gathered in Genoa because the city was the headquarters of the Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants, an organization that coordinated aid and rescue programs. The office in Genoa was headed initially by Lelio Vittorio Valobra, and later Massimo Teglio, who received help from local priests and created a regional rescue network.[18]

The German search for Jews in Genoa began on November 2, 1943, when two police agents visited the offices of the Jewish community and forced the custodians to turn over their membership lists and summon members to a synagogue meeting the next morning. Many Jews had already left the city by that time, but a majority of those who were seized in Genoa were taken at this meeting. A few members who received the summons were able to escape thanks to a warning from Massimo Teglio. Rabbi Riccardo Pacifici, who until the last moment tried to help other Jews, was captured in the Galleria Mazzini in November of that year. He was murdered at Auschwitz.[18]

In the post-war years, Genoa played a pivotal role in the Italian economic miracle, as the third corner of the so-called Industrial Triangle, formed with the manufacturing hubs of Milan and Turin. Since 1962, the Genoa International Boat Show has evolved into one of the largest annual events in Genoa. The city became an important industrial centre, giving rise to manufacturers of diving equipment (Cressi-Sub, Mares, and Techisub SpA), ferries (GNV and Home Lines, and the "OSN-Orizzonti Sistemi Navali"), oil production ("IP-Italiana Petroli"), textiles (SLAM), food services ("Elah Dufour" and "Sogegross"), construction ("FISIA-Italimpianti"), and, for a time, nuclear reactors (NIRA, which closed after the Chernobyl disaster).

Because of population growth, partly due to substantial immigration from other parts of Italy, new neighborhoods have been built. There were years of building speculation and of destruction of two historic districts of the city, the first in 1964 called "Piccapietra-Portoria" and the second in 1974 called "Madre di Dio" location of the house of Paganini; both events left indelible scars on the city and in the memory of citizens. In 1965 the political party Lotta Comunista was founded by Arrigo Cervetto and Lorenzo Parodi. A shipwreck in 1970 off the coast of Genoa, the SS London Valour, is the theme of a song by local minstrel Fabrizio De André entitled "Parlando del Naufragio della London Valour", or "Talking about the sinking of the London Valour". In 1970 the Greek student Kostas Georgakis set himself ablaze in Matteotti Square, Genoa, as a protest against the dictatorial regime of Georgios Papadopoulos. In this period Genoa was the centre of protest movements that sometimes take the form of armed struggle. In the so-called Years of Lead, the Red Brigades formed a very active column in Genoa called October 22 Group, which in 1974 kidnapped magistrate Mario Sossi and in 1979 killed worker Guido Rossa and professor Fausto Cuocolo. In 1980 the Genoese Red Brigades group was eliminated at the hands of a special detachment under the orders of Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa.

In 1991 the MT Haven was shipwrecked off the coast of Genoa, but 1992 marks the rebirth of the city with Genoa Expo '92. Genoa, city home of Christopher Columbus, celebrated the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America. For the occasion, thanks to the intervention of the architect Renzo Piano, the Old Harbour smartened up its face.

The 27th G8 summit in the city, in July 2001, was overshadowed by violent protests (Anti-globalisation movement), with one protester, Carlo Giuliani, killed. In 2007, 15 officials, including police, prison officials and two doctors, were found guilty by an Italian court of mistreating protesters (2001 Raid on Armando Diaz). Their prison sentences ranged from five months to five years.[19] In 2004, the European Union designated Genoa as the European Capital of Culture, along with the French city of Lille. In 2009 the Genoese actor and political activist Beppe Grillo founded the Five Star Movement. In 2011, Genoa, like other European cities, suffered disastrous flooding. In 2013, 11 deaths resulted from the collapse of the control tower of Genoa's port after being hit by the cargo ship Jolly Nero. In 2014, the sunken wreck from the Costa Concordia was transported to the port of Genoa to be broken up.

14 August 2018 was a black day for Genoa: the Ponte Morandi bridge collapsed, killing 43 people.[20]

See also

References

- The objects found during the works for the underground had been exposed in the exhibition Archeologia Metropolitana. Piazza Brignole e Acquasola, held at the Ligurian Archeology Museum (30 November 2009 - 14 February 2010) ( Archived December 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine)

- Melli, Piera. Genova preromana. Città portuale del Mediterraneo tra il VII e il III secolo a.C. (in Italian). Frilli. ISBN 8875633363.

- Marco Milanese, Scavi nell'oppidum preromano di Genova, L'Erma di Bretschneider, Roma 1987 on-line in GoogleBooks; Piera Melli, Una città portuale del Mediterraneo tra il VII e il III secolo a.C., Genova, Fratelli Frilli ed., 2007.

- Giulia Petracco Sicardi, "Genova", in Dizionario di toponomastica, Torino, 1990, p. 355. In Cathedral there is an inscription that says Janus, primus Rex Italiae de progenie gigantum, qui fundavit Genuam temporae Abrahae, in English, "Janus, the first King of Italy, progeny of the giants, who founded Genoa in the days of Abraham." Another theory traces the name to the Etruscan word Kainua which means "New City". Piera Melli (Genova Preromana, 2007), based on an inscription on a pottery sherd reading Kainua, suggests that the Latin name may be a corruption of an older Etruscan one with an original meaning of "new town".

- Paul the Deacon, Historia Langobardorum, II.25

- Gregory I, Registrum Epistolarum, MGH Ep. 2, XI.14, p. 274

- Paul the Deacon, Historia Langobardorum, IV.45

- Epstein, Steven A. (1996). Genoa and the Genoese, 958–1528. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8078-4992-8.

- Epstein, Steven A. (2001). Speaking of Slavery: Color, Ethnicity, and Human Bondage in Italy. Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-2512-8. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv8j5bm.

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (1987). Before Columbus: Exploration and Colonisation from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1229–1492. Philadelphia, Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1412-3.

- Early modern Italy (16th to 18th centuries) » The 17th century crisis Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Genoa 1684, World History at KMLA.

- Giorgio Bonacina, Comando Bombardieri - Operazione Europa, pp. 49-50.

- I bombardamenti sull’Italia nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale

- Enciclopedia Treccani

- L'atto di resa delle truppe tedesche

- Basil Davidson, Special Operations Europe: Scenes from the Anti-Nazi War (1980), pp. 340/360

- "The Jewish Community of Genoa". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "Italy officials convicted over G8". BBC News. 2008-07-15. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- Crollo Genova, trovato l'ultimo disperso sotto le macerie: è l'operaio Mirko. Muore uno dei feriti, le vittime totali sono 43

Bibliography

Гавриленко О. А., Сівальньов О. М., Цибулькін В. В. Генуезька спадщина на теренах України; етнодержавознавчий вимір. — Харків: Точка, 2017.— 260 с. — ISBN 978-617-669-209-6