Hinduism in Tamil Nadu

Hinduism in Tamil Nadu finds its earliest literary mention in the Sangam literature dated to the 5th century BCE. The total number of Tamil Hindus as per 2011 Indian census is 63,188,168[2] which forms 87.58% of the total population of Tamil Nadu. Hinduism is the largest religion in Tamil Nadu.

தமிழ் இந்துக்கள் | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||

| 63,188,168 (2011)[1] 87.58% of the Tamil Nadu Population | ||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||

| Tamil Nadu Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana | ||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||

| Tamil, Sanskrit | ||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Hinduism • Shaivism • Vaishnavism • Shaktism • Dravidian folk religion | ||||||||||

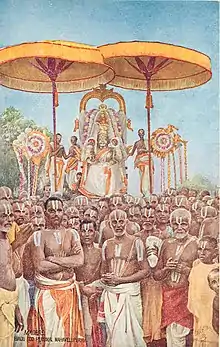

The religious history of Tamil Nadu is influenced by Hinduism quite notably during the medieval period. The twelve Alvars (poet-saints of the Vaishnava tradition) and sixty-three Nayanars (poet-saints of the Shaiva tradition) are regarded as exponents of the bhakti tradition of Hinduism in South India. Most of them came from the Tamil region and the last of them lived in the 9th century CE.

There are few worship forms and practices in Hinduism that are specific to Tamil Nadu due to the Bhakti movement spreading them across India. There are many mathas (monastic institutions) and temples based out of Tamil Nadu. In modern times, most of the temples are maintained and administered by the Hindu Religious and Endowment Board of the Government of Tamil Nadu.

History

Ancient period

Tolkappiyam, possibly the most ancient of the extant Sangam works, dated between the 3rd century BCE and 5th century CE glorified Thirumal and Murugan as the favoured god of the Tamils.[3] According to Kamil Zvelebil, Vishnu was considered ageless (The god who stays for ever) and the Supreme god of Tamils where as Skanda was considered young and a personal god of Tamils.[4][5]

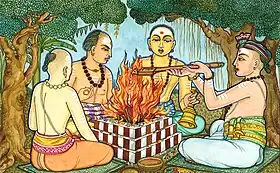

Sangam literature mentions several Hindu gods and Vedic practices around Ancient Tamilakam. Tamilians considered the Vedas as a book of Righteousness and is used to perform Yagams or Velvi.[8][9] Several kings have performed Vedic Sacrifices and prayed various gods of Hinduism. Ramachandran Nagaswamy an Indian historian, archaeologist and epigraphist states that Tamil Nadu was The Land of the Vedas and all Sangam people followed the Vedas.[10][11] King Karikala Cholan is recognised as the greatest king of the Early Cholas.[12] Karikala Cholan is mentioned in the poem 224 of Purananuru that he performed Vedic Rituals in the court of Righteousness where justice is well practiced after those conversant with proper custom.[13] The text Purananuru further mentions that Cholas were the descendants of Lunar dynasty King Shibi Chakravarthi in poem 37, 39, 43 and 46.[14] Tamils also prayed to Several Hindu gods such as Shiva,[15] Vishnu,[16][17] Brahma,[18] Durga,[17] Lakshmi,[19] Indra,[20][17] Varuna,[17] Kartikeya, and even to Avatars of Vishnu like Varaha,[21] Narasimha,[22] Vamana,[23] Parashurama,[24] Rama,[25][26][27] Balarama[28] and Krishna[29] and many other gods. The Sangam text Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai states that Lord Vishnu Who took the Vamana Avatara is the father of the four faced Brahma who was born from Vishnu's navel and from Brahma came the Chola dynasty.[18][23] the poem further mentions a Yūpa post (a form of Vedic altar) and a Brahmin village. Vedas are recited by these Brahmins, and even their parrots are mentioned in the poem as those who sing the Vedic hymns. The text states a temple for Vishnu in the city of Kanchi which is present even now, the lines 429 to 434 mention the town Thiruvekka and mentions the god Vishnu sleeping in a reclining pose. [30] Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai is one of the Eight Anthologies and is dedicated to the Hindu god Karthikeya. It also mentions many other gods Like Vishnu, Shiva, Indra, Uma, Thirty-three gods, Gandharvas, Sages.[31] Paripadal also mentions that The Thirty-three gods arose from Vishnu.[32] After the Sangam period the Alvars and Nayanmars were born. These two groups promoted Vaishnavism and Shaivism which lead to the growth of Hinduism.[33]

S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar states that the lifetime of the Vaishnava Alvars was during the first half of the 12th century, their works flourishing about the time of the revival of Brahminism and Hinduism in the north, speculating that Vaishnavism might have penetrated to the south as early as about the first century CE. There also exists secular literature that ascribes the commencement of the tradition in the south to the 3rd century CE. U.V. Swaminathan Aiyar, a scholar of Tamil literature, published the ancient work of the Sangam period known as the Paripatal, which contains seven poems in praise of Vishnu, including references to Krishna and Balarama. Aiyangar references an invasion of the south by the Mauryas in some of the older poems of the Sangam, and indicated that the opposition that was set up and maintained persistently against northern conquest had possibly in it an element of religion, the south standing up for orthodox Brahmanism against the encroachment of Buddhism by the persuasive eloquence and persistent effort of the Buddhist emperor Ashoka. The Tamil literature of this period has references scattered all over to the colonies of Brahmans brought and settled down in the south, and the whole output of this archaic literature exhibits unmistakably considerable Brahman influence in the making up of that literature.[34]

Medieval period

The Cholas who were very active during the Sangam age were entirely absent during the first few centuries. The period started with the rivalry between the Pandyas and the Pallavas, which in turn caused the revival of the Cholas. The Cholas went on to becoming a great power. Their decline saw the brief resurgence of the Pandyas. This period was also that of the re-invigorated Hinduism during which temple building and religious literature were at their best.[35]

.jpg.webp)

The Cheras ruled in southern India from before the Sangam era (300 BCE–250 CE) over the Coimbatore, Karur, Salem Districts in present-day Tamil Nadu and present day Kerala from the capital of Vanchi Muthur in the west, (thought to be modern Karur).

The Kalabhras, invaded and displaced the three Tamil kingdoms and ruled between the 3rd and the 6th centuries CE of the Sangam period. This is referred to as the Dark Age in Tamil history and Hinduism in Tamil Nadu. They were expelled by the Pallavas and the Pandyas in the 6th century. During the Kalabhras' rule, Jainism flourished in the land of the Tamils, and Hinduism was suppressed. Because the Kalabhras gave protection to Jains and perhaps Buddhists, too, some have concluded that they were anti-Hindu, although this latter view is disputed.

During the 4th to 8th centuries CE, Tamil Nadu saw the rise of the Pallavas under Mahendravarman I and his son Mamalla Narasimhavarman I.[36] Pallavas ruled a large portion of South India with Kanchipuram as their capital. Mahendra Varman was principally a Buddhist, but converted to Hinduism by the influence of Shaiva saints. It was under him that Dravidian architecture reached its peak with the Pallava built Hindu temples. Narasimhavarman II built the Shore Temple which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Pallavas were replaced by the Cholas as the dominant kingdom in the 10th century CE and they in turn were replaced by Pandyas in the 13th century CE with their capital as Madurai. Temples such as the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai and Nellaiappar Temple at Tirunelveli are the best examples of Pandyan temple architecture.[37]

Chola Empire

By the 9th century CE, during the times of the second Chola monarch Aditya I, his son Parantaka I, Parantaka Chola II itself the Chola empire had expanded into what is now interior Andhra Pradesh and coastal Karnataka, while under the great Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola, the Cholas rose as a notable power in south Asia.

The Cholas excelled in building magnificent temples. Brihadeshwara Temple in Thanjavur is a classical example of the magnificent architecture of the Chola kingdom. Brihadshwara temple is an UNESCO Heritage Site under "Great Living Chola Temples."[38] Some examples are Tiruvarur Thyagaraja Swamy temple known as Thirumoolasthanam, Annamalaiyar Temple located at the city of Tiruvannamalai and the Chidambaram Temple in the heart of the temple town of Chidambaram. With the decline of the Cholas between 1230 and 1280 CE, the Pandyas rose to prominence once again, under Maravarman Sundara Pandya and his younger brother, the celebrated Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan. This revival was short-lived as the Pandya capital of Madurai itself was sacked by Alauddin Khalji's troops under General Malik Kafur in 1316 CE.[39]

Vijayanagara and Nayak period (1336–1646)

The Muslim invasions triggered the establishment of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire in the Deccan. It eventually conquered the entire Tamil country (c. 1370 CE). This empire lasted for almost two centuries, till the defeat of Vijayanagara in the Battle of Talikota in 1565. Subsequent to this defeat, according to the author Nilakanta Sastri, "many incompetent kings succeeded to the throne of Vijayanagara, with the result that its grip loosened over its feudatories among whom the Nayaks of Madurai and Tanjore, were among the first to declare their independence, despite initially maintaining loose links with the Vijayanagara kingdom".[40] As the Vijayanagara Empire went into decline after mid-16th century, the Nayak governors, who were appointed by the Vijayanagara kingdom to administer various territories of the empire, declared their independence. The Nayaks of Madurai and Nayaks of Thanjavur were most prominent of them all, in the 17th century. They reconstructed some of the oldest temples in the Tamil country, such as the Meenakshi Temple.

Rule of Nawabs, Nizams, and British (1692–1947)

In the early 18th century, the eastern parts of Tamil Nadu came under the dominions of the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Nawab of the Carnatic. While Wallajah was supported by the English, Chanda Shahib was supported by the French by the middle of the 18th century. In the late 18th century, the western parts of Tamil Nadu, came under the dominions of Hyder Ali and later Tipu Sultan, particularly with their victory in the Second Anglo-Mysore War. After winning the Polygar wars, the East India Company consolidated most of southern India into the Madras Presidency coterminous with the dominions of Nizam of Hyderabad. Pudukkottai remained as a princely state. The Hindu temples were kept intact during this period, and there is no notable destruction recorded.

Tamil Nadu in the Republic of India (1947–present)

When India became independent in 1947, Madras Presidency became Madras State, comprising present day Tamil Nadu, coastal Andhra Pradesh, South Canara district Karnataka, and parts of Kerala. The state was subsequently split up along linguistic lines. In 1969, Madras State was renamed Tamil Nadu, meaning Tamil country.

The total number of Tamil Hindus as per 2011 Indian census is 63,188,168 which forms 87.58% of the total population of Tamil Nadu.[41]

| Parameter | Population |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 54985079 |

| Literates Population | 35011056 |

| Workers Population | 25241725 |

| Cultivators Population | 4895487 |

| Agricultural Workers Population | 8243512 |

| HH Industry Workers Population | 1330857 |

| Other Workers Population | 10771869 |

| Non-Workers Population | 29743354 |

Saints

The twelve Alvars (saint poets of Vaishnava tradition) and sixty-three Nayanars (saint poets of Shaiva tradition) are regarded as exponents of the bhakti tradition of Hinduism in South India.[43] Most of them came from the Tamil region and the last of them lived in the 9th century CE. Composers of Tevaram – the Tamil saint poets of 7th century namely Appar, Tirugnana Sambandar and Sundarar with the 9th-century poet Manickavasagar, the composer of Tiruvacakam were saints of Shaivism. The Shaiva saints have revered 276 temples in Tevaram and most of them are in Tamil Nadu on both shores of river Cauvery. Vaippu Sthalangal are a set of 276 places having Shiva temples that were mentioned casually in the songs in Tevaram.[44] The child poet, Tirugnana Sambandar was involved in converting many people from Buddhism and Jainism to Hinduism. The saint Appar was involved in Uḻavatru padai, a cleaning and remodification initiative of dilapidated Shiva temples. The Alvars, the 12 Vaishnava saint poets of 7th-9th century composed the Divya Prabandha, a literary work praising god Vishnu in 4000 verses.

The development of Hinduism grew up in the temples and mathas of medieval Tamil Nadu with self-conscious rejection of Jain practises.[45]

Monastic institutions

Vaishnava

Parakala matha was the first monastery of the Sri Vaishnava sect of Brahmin Hindu society. The matha was first established by Brahmatantra Swatantra Jeeyar, a disciple of Sri Vedanta Desika by 1268 CE. The matha got the name "Parakala" by the grace of Tirumangai Alvar also known as Parakalan. The head of this matha is the hereditary Acharya of the Mysore Royal Family. The Hayagriva idol worshipped here is said to be handed down from Vedanta Desika.[46]

Ahobila Matham (also called Ahobila Matam) is a Vadakalai Sri Vaishnava religious institution established 600 years ago at Ahobilam in India by Athivan Satakopa Svami (originally known as Srinivasacharya).[47][48][49] Athivan Sathakopa, a Vadakalai Brahmin,[50] who was a great grand disciple of Vedanta Desikan[51][52] and a disciple of Brahmatantra Swatantra Jiyar of the Parakala matha,[53] founded and established the matha, based on the Pancharatra tradition.[54][55][56] Since then a succession of forty-six ascetics known as Aḻagiya Singar have headed the monastic order.

Smartha

The Smartha ritualistic form of Hinduism was introduced into the Tamil lands closer to the 5th-6th century CE, it soon became the standard form of Hinduism in the Tamil country and was propagated as such by the different ruling dynasties in Tamil Nadu, the Shaiva and Vaishnava moments started as a result of this introduction. The Kanchi matha serves as the foremost Smartha institution in the state, Kanchi Matha's official history states that it was founded by Adi Sankara of Kaladi, and its history traces back to the fifth century BCE.[58] A related claim is that Adi Sankara came to Kanchipuram, and that he established the Kanchi matha named "Dakshina Moolamnaya Sarvagnya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetam" in a position of supremacy (Sarvagnya Peetha) over the other mathas of the subcontinent, before his death there. Other sources give the place of his death as Kedarnath in the Himalayas.[59][60]

Shaiva

Madurai Adheenam is the oldest Shaiva matha in South India established around 600 CE by saint Campantar. It is located two blocks from the huge Madurai Meenakshi Amman Temple, one of the most famous Siva-Shakthi shrines in the world. It is an active centre of Saiva Siddantha philosophy. It is currently headed by Sri Arunagirinatha Gnanasambantha Desika Paramacharya.[61] The adheenam is the hereditary trustee of four temples in Thanjavur District.

Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam is a matha based in the town of Thiruvaduthurai in Kuthalam taluk of Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu, India.[62] As of 1987, there were a total of 15 Shiva temples under the control of the adheenam.[63]

Dharmapuram Adheenam is a matha based in the town of Mayiladuthurai, India. As of 1987, there were a total of 27 Shiva temples under the control of the adheenam.[63]

Deities

Hinduism is a diverse system of thought with beliefs spanning monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism, monism, atheism, agnosticism, gnosticism among others;[64][65][66][67] and its concept of God is complex and depends upon each individual and the tradition and philosophy followed. It is sometimes referred to as henotheistic (i.e., involving devotion to a single god while accepting the existence of others), but any such term is an overgeneralisation.[68]

The major worship forms of Vishnu is worshipped directly, or in the form of his ten avatars, the most famous of whom are Rama and Krishna. Lord Shiva is worshipped directly in the form of lingam with Ganesha, Murugan and Parvathi in seprate shrines.[69]

Perumal

Perumal (Tamil: பெருமாள்), also rendered Thirumal, is a form of Vishnu worshipped in the Sri Vaishnava tradition. He is also venerated by the epithets of Narayana, Varadharaja, Rangaraja, Ranganatha, Kallalagar, Govindaraja, and several others in his temples scattered throughout the Tamil country. Originally venerated as the god of the forests, Perumal was assimilated with Vaishnavism, having earlier conceived been as either a pantheistic or a monotheistic divinity. Through the concept of bhakti, first introduced to the region by the Alvars, Vaishnavism became among the oldest faiths to influence the Tamil people.[70] The deity, and his consort Lakshmi, as well as her aspects of Sridevi, Bhudevi, and Niladevi, are primarily venerated, and are also represented as the Dashavatara in Perumal temples in Tamil Nadu. He is the deity who is primarily addressed in the Naalayira Divya Prabandham, a compilation of works by the Alvar saints, whose philosophy and hymns were propagated in the works of Ramanuja, Manavala Mamunigal, and Vedanta Desikan.[71] The largest Hindu temple in India is dedicated to Perumal in his form of Ranganathaswamy, situated at Srirangam.[72] The Alvars influenced the establishment of the Divya Desams, 108 shrines of Perumal that were glorified in their works, which continue to be visited as major shrines of pilgrimage by Tamil Vaishnavas.[73]

Number of poems echo the Hindu puranic legends about Parashurama, Rama, Krishna and others in the Akanaṉūṟu .[74][75] According to Alf Hiltebeitel – an Indian Religions and Sanskrit Epics scholar, the Akanaṉūṟu has the earliest known mentions of some stories such as "Krishna stealing sarees of Gopis" which is found later in north Indian literature, making it probable that some of the ideas from Tamil Hindu scholars inspired the Sanskrit scholars in the north and the Bhagavata Purana, or vice versa.[29] However the text Harivamsa which is complex, containing layers that go back to the 1st or 2nd centuries BCE, Consists the parts of Krishna Playing with Gopis and stealing sarees.

Tamil Sangam literature (200 BCE to 500 CE) mentions Mayon or the "dark one," as the supreme deity who creates, sustains, and destroys the universe and was worshipped in the mountains of Tamilakam. The verses of Paripadal describe the glory of Perumal in the most poetic of terms.

தீயினுள் தெறல் நீ; |

In fire, you are the heat; |

| —Paripadal, iii: 63–68 | —F Gros, K Zvelebil[76] |

Lord Rama

Sri Ramachandra also simply called Rama is one of the deities best-known and most widely worshipped in Hinduism, especially Vaishnavism. He is the seventh and one of the most popular avatars of Vishnu. In Rama-centric traditions of Hinduism, he is considered the Supreme Being.[77] The earliest reference to the story of the Ramayana is found in the Sangam literature.

Purananuru which is dated from 1st century BCE and 5th century CE.[78] Purananuru 378, attributed to the poet UnPodiPasunKudaiyar, written in praise of the Chola king IlanCetCenni. The poem makes the analogy of a poet receiving royal gifts and that worn by the relatives of the poet as being unworthy for their status, to the event in the Ramayana, where Sita drops her jewels when abducted by Ravana and these jewels being picked up red-faced monkeys who delightfully wore the ornaments (Hart and Heifetz, 1999, pp. 219–220).[25][26]

Akanaṉūṟu, which is dated between 1st century BCE and 2nd century CE, has a reference to the Ramayana in poem 70. The poem places a triumphant Rama at Dhanushkodi, sitting under a Banyan tree, involved in some secret discussions, when the birds are chirping away.[27]

The Silappatikaram (translated as The Tale of an anklet) written by a prince turned Jain monk Ilango Adigal, dated to the 2nd century AD or later. The epic narrates the tale of Kovalan, son of a wealthy merchant, his wife Kannagi, and his lover Madhavi, and has many references to the Ramayana story. It describes the fate of Poompuhar suffering the same agony as experienced by Ayodhya when Rama leaves for exile to the forest as instructed by his father (Dikshitar, 1939, p. 193). The Aycciyarkuravai section (canto 27), makes mention of the Lord who could measure the three worlds, going to the forest with his brother, waging a war against Lanka and destroying it with fire (Dikshitar, 1939, p. 237). This seems to imply on Rama being regarded as divinity, rather than a mere human. These references indicate that the author was well aware of the story of the Ramayana in the 2nd century AD.[79]

Manimekalai written as the sequel to the Silappatikaram by the Buddhist poet Chithalai Chathanar, narrates the tale of Manimekalai, the daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi, and her journey to become a Buddhist Bhikkuni. This epic also makes several references to the Ramayana, such as a setu (bridge) being built by monkeys in canto 5, line 37 (however the location is Kanyakumari rather than Dhanushkodi). In another reference, in canto 17, lines 9 to 16, the epic talks about Rama being the incarnate of Trivikrama or Netiyon, and he building the setu with the help of monkeys who hurled huge rocks into the ocean to build the bridge. Further, canto 18, lines 19 to 26, refers to the illegitimate love of Indra for Ahalya the wife of Rishi Gautama(Pandian, 1931, p. 149)(Aiyangar, 1927, p. 28).[80][81][82]

Pillayar

Ganesha, also spelled Ganesa or Ganesh, also known as Ganapati, Vinayaka, and Pillaiyar (Tamil: பிள்ளையார், lit. 'Piḷḷaiyār'), is one of the deities best-known and most widely worshipped in the Hindu pantheon.[83] Ganesa is the first son of Shiva and is given the primary importance in all Shiva temples with all worship starting from him. Local legend states the Tamil word Pillayar splits into Pillai and yaar meaning who is this son, but scholars believe it is derived from the Sanskrit word pulisara meaning elephant.[84] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (1963:57-58) thinks that Pallavas adopted the Ganesa motif from Chalukyas.[85] During the 7th century, Vatapi Ganapati idol was brought from Badami (Vatapi - Chalukya capital) by Paranjothi, the general of Pallavas who defeated Chalukyas.[86] In modern times, there are separate temples for Ganesha in Tamil Nadu.

Murugan

Murugan (Tamil: முருகன்) also called Kartikeya, Skanda and Subrahmanya, is a popular deity among the Tamil people, famously referred as Tamil Kadavul (God of Tamils). He is often regarded as the patron deity of the Tamil land (Tamil Nadu).[87] Tolkappiyam, possibly the most ancient of the extant Sangam works, dated between the 3rd century BCE and 5th century CE glorified Murugan, " the red god seated on the blue peacock, who is ever young and resplendent," and " the favoured god of the Tamils."[3] Efforts were made to incorporate Murugan into both Vaishnavism and Shaivism, with the deity regarded as the son-in-law of Vishnu, and the son of Shiva. The Sangam poetry divided space and Tamil land into five allegorical areas and according to the Tirumurugarruppatai (circa 400-450 CE) attributed to the great Sangam poet Nakkiirar, Murugan was the presiding deity of the Kurinci region (hilly area). Tirumurugaruppatai is a deeply devotional poem included in the ten idylls (Pattupattu) of the age of the third Sangam.[88] The cult of Skanda disappeared during the 6th century and was predominantly expanded during late 7th century Pallava period - Somaskanda sculptured panels of the Pallava period stand as a testament.[89]

Shiva

Lingam

The Lingam is a representation of the Hindu deity Shiva used for worship in Hindu temple.[90] The lingam is the principal deity in most Shiva temples in South India. The propagation of linga worship on a large scale in South India is believed to be from Chola times (late 7th century CE), through Rig veda, the oldest literature details about worshipping Shiva in the form of linga.[91] Pallavas propagated Somaskanda as the principal form of worship, slightly deviating from the Shaiva agamas; Cholas being strict shaivas, established lingams in all the temples.[92]

Lingothbhavar

Lingothbhavar or emergence of linga, found in Shiva Purana as a symbol of Shiva, augments the synthesis of the old cults of pillar and phallic worship.[93] The idea emerged from deity residing in a pillar and later visualised as Shiva emerging from the lingam[94] The lingothbhavar image can be found in the first precinct around the sanctum in the wall exactly behind the image of Shiva. Appar, one of the early Shaiva saint of the 7th century, gives evidence of this knowledge of puranic episodes relating to Lingothbhavar form of Shiva while Tirugnana Sambandar refers this form of Shiva as the nature of light that could not be comprehended by Brahma and Vishnu.[95]

Nataraja

Nataraja or Nataraj, The Lord (or King) of Dance; (Tamil: கூத்தன் (Kooththan)) is a depiction of the Hindu god Shiva as the cosmic dancer Koothan who performs his divine dance to destroy a weary universe and make preparations for god Brahma to start the process of creation. A Tamil concept, Shiva was first depicted as Nataraja in the famous Chola bronzes and sculptures of Chidambaram. The dance of Shiva in Tillai, the traditional name for Chidambaram, forms the motif for all the depictions of Shiva as Nataraja.[96][97][98] The form is present in most Shiva temples in South India, and is the main deity in the famous temple at Chidambaram.[99]

Dakshinamurthy

Dakshinamurthy or Jnana Dakshinamurti (Tamil: தட்சிணாமூர்த்தி, IAST:Dakṣiṇāmūrti)[100] is an aspect of Shiva as a guru (teacher) of all fields. This aspect of Shiva is his personification of the ultimate awareness, understanding and knowledge.[101] The image depicts Shiva as a teacher of yoga, music, and wisdom, and giving exposition on the shastras (vedic texts) to his disciples.[102]

Somaskandar

Somaskanda derives from Sa (Shiva) with Uma (Parvathi) and Skanda (child Murugan).[103] It is the form of Shiva where he is accompanied by Skanda the child and Paravati his consort[104] in sitting posture. Though it is a Sanskrit name, it is a Tamil concept and Somaskandas are not found in North Indian temples.[105] In the Tiruvarur Thygarajar Temple, the principal deity is Somaskanda under the name of Thyagaraja.[104] All temples in the Thygaraja cult have images of Somaskandar as Thyagarajar - though iconographically similar, they are iconologically different. Architecturally when there are separate shrines dedicated to the utsava(festival deity) of Somaskanda, they are called Thyagaraja shrines.[106] Unlike Nataraja, which is a Chola development, Somaskanda was prominent even during the Pallava period much earlier to Cholas.[107] References to the evolution of the Somaskanda concept are found from Pallava period from the 7th century CE in carved rear stone walls of Pallava temple sanctums.[108] Somaskanda was the principal deity during Pallava period replacing lingam, including the temples at Mahabalipuram, a UNESCO world heritage site. But the cult was not popular and Somaskanda images were relegated to subshrines.[109] Sangam literature does not mention Somaskanda and references in literature are found in the 7th-century Tevaram.[108]

Bhairavar

Bhairava is one of the eight forms of Shiva, and translation of the adjectival form as "terrible" or "frightful". Bhairava is known as Vairavar in Tamil where he is often presented as a Grama Devata or folk deity who safeguards the devotee on all eight directions. In Chola times Bhairava is referred as Bikshadanar, a mendicant, and the image can be found in most Chola temples.[110]

Dravidian folk religion

- Ayyanar (Tamil: ஐயனார்) is worshipped as a guardian deity predominantly in Tamil Nadu and Tamil villages in Sri Lanka. The earliest reference to Aiynar-Shasta includes two or more hero stones to hunting chiefs from the Arcot district in Tamil Nadu. The hero stones are dated to the 3rd century CE. It reads "Ayanappa; a shrine to Cattan." This is followed by another inscription in Uraiyur near Tiruchirapalli which is dated to the 4th century CE.[111] Literary references to Ayyanar-Cattan is found in Silappatikaram, a Tamil Jain work dated to the 4th to 5th century CE.[112] From the Chola period (9th century CE) onwards the popularity of Ayyanar-Shasta became even more pronounced.[113]

- Madurai Veeran (Tamil: மதுரை வீரன், romanized: Warrior of Madurai, lit. 'Maturai Vīraņ') is a Tamil folk deity popular in southern Tamil Nadu. His name was derived as a result of his association with the southern city of Madurai as a protector of the city.[114]

- Kālī (Tamil: காளி) is the Hindu goddess associated with power, shakti. Kālī is represented as the consort of Shiva, on whose body she is often seen standing. She is associated with many other Hindu goddesses like Durga, Bhadrakali, Sati, Rudrani, Parvati and Chamunda. She is the foremost among the Dasa Mahavidyas, ten fierce Tantric goddesses.[115]

- Muneeswarar (Tamil முனீஸ்வரன்) is a Hindu god. 'Muni' means 'saint' and 'iswara' represents 'Shiva'. He is considered as a form of Shiva, although no scriptural references have been found to validate such claims. He is worshiped as a family deity in most Shaiva families.

- Karuppu Sami (Tamil: கருப்புசாமி) (also called by many other names) is one of the regional Tamil male deities who is popular among the rural social groups of South India, especially Tamil Nadu and small parts of Kerala. He is one of the 21 associate folk-deities of Ayyanar and is hence one of the so-called Kaval Deivams of the Tamils.

- Sudalai Madan or Madan, is a regional Tamil male deity who is popular in South India, particularly Tamil Nadu. He is considered to be the son of Shiva and Parvati. He seems to have originated in some ancestral guardian spirit of the villages or communities in Tamil Nadu, in a similar manner as Ayyanar.

These deities are primarily worshipped by agrarian communities. Unlike the Vedic traditions, these deities generally do not abide in temples, but in shrines in the open. These gods are primarily worshipped through festivals throughout the year, during important occasions like harvest or sowing time. To propitiate these gods, the villagers make sacrifices of meat (usually goats) and arrack, which is then shared among all the village. In addition, the mantras are not restricted to Sanskrit and are performed in Tamil. Worship of these deities is oftentimes seen as the modern continuation of the Dravidian folk religion followed before the Indo-Aryan migration into Indian subcontinent. Similar practices exist among the Kannada and Telugu non-Brahmin castes and Dravidian tribes of Central India.

Caste

A steeply classified class structure existed in Tamil Nadu from around 2000 years because of the correlation in the form of cultivation, population and centralization of political system. These classes in turn are grouped into social groups especially in rural areas. The shape of class system in rural Tamil Nadu has changed dramatically because of land reform acts like 'Green Revolution'.[116] As per 2001 census, there was a total of 11,857,504 people in Scheduled castes (SC) constituting 19% of Tamil Nadu and 7.1% of SC population in India.[117] Leaving 840 in Buddhism and 837 in Sikhism, leaving the remaining 1,18,55,827 in Hinduism.[117] The literacy rate (who can read, write and understand) among these stands at 63.2% which is lower than the 73.5% state level literacy rate.[117]

Self-Respect Movement

The Self-Respect Movement is a movement with the purported aim of achieving a society where backward castes have equal human rights,[118] and encouraging backward castes to have self-respect in the context of a caste based society that considered them to be a lower end of the hierarchy.[119] It was founded in 1925 by E. V. Ramasamy (called Periyar by supporters) in Tamil Nadu, India. Ramasamy's movement espoused atheism and rationalism, and was a proponent of anti-Brahminism.[120] He also encouraged members of the lower sections of society to convert to Christianity or Islam.[121] He also claimed that Muslims follow the ancient philosophy of the Dravidians.[122] A number of political parties in Tamil Nadu, such as Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) owe their origins to the Self-respect movement,[123] the latter a 1972 breakaway from the DMK. Both parties are populist with a generally social democratic orientation.[124]

Caste-based political parties

Caste based political parties were not successful during the 1960s to late 80s when the Indian National Congress, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam were dominant. Three of the parties emerged prominent - Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) among Vanniyar, Puthiya Tamilagam among Devendrar and Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi among Paraiyar polled 12% vote in the 1999 Loksabha elections.[125] After 1931, caste based census was not performed and hence the census data is not available for other castes.[126]

References

References

- "Tamil Nadu Population Census data 2011". Census 2011 - Census of India.

- "Tamil Nadu Population Census data 2011". Census 2011 - Census of India.

- Sri, Padmanabhan S. (1984). "The Blend of Sanskrit Myth and Tamil Folklore in "Thiru-murugātru-p-padai"". Asian Folklore Studies. 43 (1): 133–140. doi:10.2307/1178103. ISSN 0385-2342. JSTOR 1178103.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (6 October 1974). Tamil Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447015820.

- A HISTORY OF INDIAN LITERATURE volume 10 TAMIL LITERATURE page number 49 written by Kamil Zvelebil

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 400 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 166 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 362 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 15 by George L. III Hart".

- "Vedic route to the past". The Hindu. 23 June 2016.

- "The cultural connection". The Hindu. 5 July 2012.

- "The great Cholas through the ages".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 224 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 46 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 1 by George L. III Hart".

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 57 by George L. III Hart".

- Journal of Tamil Studies, Volume 1. International Institute of Tamil Studies. 1969. p. 131. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- "Pattupattu Ten Tamil Idylls Chelliah J. V."

- "Pattupattu Ten Tamil Idylls Chelliah J. V."

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 241 by George L. III Hart".

- Paripadal Poem 2 Lines 16 to 19

- Paripadal Poem 4 Lines 10 to 20

- "Pattupattu Ten Tamil Idylls Chelliah J. V."

- Akananuru poem 220

- Hart, George L; Heifetz, Hank (1999). The four hundred songs of war and wisdom : an anthology of poems from classical Tamil : the Puṟanāṉūṟu. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231115629.

- Kalakam, Turaicămip Pillai, ed. (1950). Purananuru. Madras.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dakshinamurthy, A (July 2015). "Akananuru: Neytal – Poem 70". Akananuru. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Poem: Purananuru - Part 58 by George L. III Hart".

- Alf Hiltebeitel (1988). The Cult of Draupadī: Mythologies from Gingee to Kurukserta. University of Chicago Press (Motilal Banarsidass 1991 Reprint). pp. 188–190. ISBN 978-81-208-1000-6.

- "Pattupattu Ten Tamil Idylls Chelliah J. V."

- "Pattupattu Ten Tamil Idylls Chelliah J. V."

- Paripadal Poem 3 lines 1 to 14

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Stephen N. Hay; William Theodore De Bary (1988). Sources of Indian Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-231-06651-8.

- Aiyangar, Krishnaswami (2019). Early History of Vaishnavism in South India. Forgotten Books. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-243-64916-7.

- Sastri 2002, p. 387

- Sastri 2002, pp. 91–92

- V.K. Subramanian 2003, pp. 96–98

- "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Cotterell 2011, p. 190

- 'Advanced History of India', K.A.Nilakanta Sastri (1970)p. 181-182, Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi

- "Tamil Nadu Population Census data 2011". Census 2011 - Census of India.

- "Directorate of Census Operations - Tamil Nadu". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Klostermaier 2007, p. 255.

- "India Independence With Kolaru Pathigam". fasrjoint. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Cort 1998, p. 208.

- Swahananda, Swami (1989). Monasteries in South Asia. Vedanta Press. p. 50. ISBN 9-780-874-81047-9.

- Pg.557 The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Delhi sultanate; Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti

- Sastry, Sadhu Subrahmanya (1984). Report on the Inscriptions of the Devasthanam Colle[c]tion, with Illustrations. Sri Satguru Publications.

- Tatacharya, R. Varada (1978). The Temple of Lord Varadaraja, Kanchi. Sri Tatadesika Tiruvamsastar Sabha.

- Reddy, Ravula Soma (1984). Hindu and Muslim Religious Institutions, Andhra Desa, 1300-1600. New Era. pp. 36.

- Narasimhachary, Mudumby (2004). Śrī Vedānta Deśika. Sahitya Akademi. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-260-1890-1.

- Sharma, M. H. Rāma (1978). The History of the Vijayanagar Empire: Beginnings and expansion, 1308-1569. Popular Prakashan. p. 52.

- Bhatnagar, O. P. (1964). Studies in Social History: Modern India. St. Paul's Press Training School. pp. 129.

- Jamanadas, K. (1991). Tirupati Balaji was a Buddhist Shrine. Sanjivan Publications.

- "Vadakalai Srivaishnava Festivals' Calendar - The source mentions Pancharatra & Munitraya Krishna Jayantis celebrated by Ahobila Mutt & Andavan Ashrams respectively". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Ahobila Mutt's Balaji Mandir Pune, Calendar - The calendar mentions Ahobila Mutt disciples celebrating Krishna Jayanti as "Pancharatra Sri Jayanti". Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- kamakoti.org

- "(52) The dynasties of Magadh after the Mahabharat war and the important historical personalities (Gautam Buddh, Chandragupt Maurya, Jagadguru Shankaracharya, and Vikramaditya)". encyclopediaofauthentichinduism.org. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "Page Two - (53) Chronological chart of the history of Bharatvarsh since its origination". encyclopediaofauthentichinduism.org. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Swami, Satguru Sivaya Subramaniya (2002). How To Become A Hindu. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 387. ISBN 978-81-208-1811-8.

- "Census of India, 1981: Tamil Nadu". Economic and Political Weekly: A Sameeksha Trust Publication. Controller of Publications: 7. 1962. ISSN 0012-9976.

- M. Thangaraj (2003). Tamil Nadu: an unfinished task. SAGE Publications. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-7619-9780-1.

- Rogers, Peter (2009), Ultimate Truth, Book 1, AuthorHouse, p. 109, ISBN 978-1-4389-7968-7

- Chakravarti, Sitansu (1991), Hinduism, a way of life, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 71, ISBN 978-81-208-0899-7

- "Polytheism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (2002), The man who was a woman and other queer tales of Hindu lore, Routledge, p. 38, ISBN 978-1-56023-181-3

- See Michaels 2004, p. xiv and Gill, N.S. "Henotheism". About, Inc. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- Matchett 2000, p. 4.

- History of People and Their Environs: Essays in Honour of Prof. B.S. Chandrababu. Bharathi Puthakalayam. 2011. p. 47. ISBN 978-93-80325-91-0.

- Hopkins, Steven Paul (18 April 2002). Singing the Body of God: The Hymns of Vedantadesika in Their South Indian Tradition. Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-802930-4.

- BPI. Little Known Facts About India. BPI Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-81-8497-295-5.

- Rajarajan, R.K.K. (1 January 1970). "Historical sequence of the Vaiṣṇava Divyadeśas. Sacred venues of Viṣṇuism". Acta Orientalia. 74: 37–90. doi:10.5617/ao.4468. ISSN 1600-0439. S2CID 230924123.

- Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 53–54.

- Raoul McLaughlin (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. A&C Black. pp. 48–50. ISBN 978-1-84725-235-7.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1974). Tamil Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-447-01582-0.

- Tulasīdāsa (1999). Sri Ramacaritamanasa. Translated by Prasad, RC. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 871–872. ISBN 978-81-208-0762-4.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1.

- Dikshitar, V R Ramachandra (1939). The Silappadikaram. Madras, British India: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Pandian, Pichai Pillai (1931). Cattanar's Manimekalai. Madras: Saiva Siddhanta Works. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Aiyangar, Rao Bahadur Krishnaswami (1927). Manimekhalai In Its Historical Setting. London: Luzac & Co. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Shattan, Merchant-Prince (1989). Daniélou, Alain (ed.). Manimekhalai: The Dancer With the Magic Bowl. New York: New Directions.

- Rao & Rao 1989, p. 1

- Brown 1991, p. 25.

- Clothey 1978, p. 221

- "Vatapi Ganapati". Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Cage of Freedom By Andrew C. Willford

- Krishan 1999, p.59

- Krishan 1999, p.60

- Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, by Jeanne Fowler, pgs. 42-43, at Books.Google.com

- Vasudevan 2000, p. 105.

- Vasudevan 2000, p. 106

- Anand 2004, p. 132

- Vasudevan 2000, p. 105

- Parmeshwaranand 2001, p. 820

- Singh 2009, p. 1079

- National Geographic 2008, p. 268

- Soundara Rajan 2001, p. 263-264

- G. Vanmikanathan. (1971). Pathway to God through Tamil literature, Volume 1. A Delhi Tamil Sangam Publication.

- . For iconographic description of the Dakṣiṇāmūrti form, see: Sivaramamurti (1976), p. 47.

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dallapiccola

- For description of the form as representing teaching functions, see: Kramrisch, p. 472.

- Pal 1988, p. 271

- Smith 1996, p. 203

- Ghose 1996, p. 3

- Ghose 1996, p. 11

- Smith 1996, p. 205

- Ghose 1996, p. 12

- Vasudevan 2000, pp. 39–40

- Dehejia 1990, p. 21

- Williams 1981, p.67

- Williams 1981, p.66

- Williams 1981, p.62

- Stephanides 1994, p. 146

- Encyclopedia International, by Grolier Incorporated Copyright in Canada 1974. AE5.E447 1974 031 73-11206 ISBN 0-7172-0705-6 page 95

- Driver & Driver 1987, p. 6

- "Tamil Nadu DATA HIGHLIGHTS: THE SCHEDULED CASTES Census of India 2001" (PDF). Census of India. National Informatics Centre. 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- N.D. Arora/S.S. Awasthy (2007). Political Theory and Political Thought. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 978-81-241-1164-2.

- Thomas Pantham; Vrajendra Raj Mehta; Vrajendra Raj Mehta (2006). Political Ideas in Modern India: thematic explorations. Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-3420-0.

- Omvedt, Gail (2006). Dalit visions : the anti-caste movement and the construction of an Indian identity (Rev. ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2895-1. OCLC 212627760.

- Diehl, Anita (1977). E.V. Ramaswami Naicker-Periyar : a study of the influence of a personality in contemporary South India. Stockholm: Esselte studium. ISBN 91-24-27645-6. OCLC 4465718.

- More, J. B. P. (2004). Muslim identity, print culture, and the Dravidian factor in Tamil Nadu. Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2632-0. OCLC 59991703.

- Shankar Raghuraman; Paranjoy Guha Thakurta (2004). A Time of Coalitions: Divided We Stand. Sage Publications. p. 230. ISBN 0-7619-3237-2.

Self-respect movement DMK AIADMK.

- Christopher John Fuller (2003). The Renewal of the Priesthood: Modernity and Traditionalism in a South Indian Temple. Princeton University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-691-11657-1.

- Wyatt & Zavos 2003, p. 126

- "Census of India - Census Terms". Census of India. National Informatics Centre. 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

Citations

- Anand, Swami P.; Swami Parmeshwaranand (2004). Encyclopaedia of the Śaivism. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-427-4.

- Brown, Robert (1991). Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Albany: State University of New York. ISBN 0-7914-0657-1.

- Cort, John (1998). Open boundaries: Jain communities and culture in Indian history. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9985-6.

- Clothey, Fred W. (1978). The many faces of Murukan̲: the history and meaning of a South Indian god. Hague: Mouton Publishers. ISBN 90-279-7632-5.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2011). Asia: A Concise History. Delhi: John Wiley & Sons(Asia) Pte. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-470-82958-5..

- Dehejia, Vidya (1990). Art of the imperial Cholas. USA: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07188-4.

- Driver, Edwin D.; Driver, Aloo E. (1987). Social class in urban India: essays on cognitions and structures. Netherlands: E. J. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-08106-2.

- Ghose, Rajeshwari (1996). The Tyāgarāja cult in Tamilnāḍu: a study in conflict and accommodation. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 81-208-1391-X.

- Klostermaier, K (2007) [1994]. A Survey of Hinduism (3rd ed.). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

- Matchett, Freda (2000). Krsna, Lord or Avatara? the relationship between Krsna and Visnu: in the context of the Avatara myth as presented by the Harivamsa, the Visnupurana and the Bhagavatapurana. Surrey: Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 0-7007-1281-X.

- Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Translated by Harshav, Barbara. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08953-9.

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta (2002) [1955]. A History of South India, From Prehistoric times to fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: OUP. ISBN 0-19-560686-8..

- National Geographic (2008). Sacred Places of a Lifetime: 500 of the World's Most Peaceful and Powerful Destinations. United States: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0336-7.

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1988). Indian Sculpture: 700-1800 Volume 1. New Delhi: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. ISBN 81-7017-383-3.

- Parmeshwaranand, Swami; Swami Parmeshwaranand (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas: Volume 3.(I-L). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-226-3.

- Rao, Saligrama Krishna Ramachandra; Rao, Rama R. (1989). Āgama-kosha. Kalpatharu Research Academy. Kalpatharu Research Academy..

- Singh, Sarina; Lindsay Brown; Mark Elliott; Paul Harding; Abigail Hole; Patrick Horton (2009). Lonely Planet India. Australia: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-151-8.

- Smith, David (1996). The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India. United Kingdom: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-48234-8.

- Soundara Rajan, Kodayanallur Vanamamalai (2001). Concise classified dictionary of Hinduism. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-857-3.

- Stephanides, Stephanos (2001). Concise classified dictionary of Hinduism. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-857-3.

- Vasudevan, Geetha (2000). anslating Kali's feast: the goddess in Indo-Caribbean ritual and fiction. Atlanta: Rodopi B.V. ISBN 90-420-1381-8.

- V.K. Subramanian (2003). Art shrines of ancient India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-431-7..

- Williams, Joanna (1981). Kaladarsana: American studies in the art of India. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

- Wyatt, Andrew; Zavos, John (2003). Decentring the Indian Nation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5387-7.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)