Hilde Holger

Hilde Boman-Behram (née Hilde Sofer, stage name Hilde Holger; 18 October 1905 – 22 September 2001) was an expressionist dancer, choreographer and dance teacher whose pioneering work in integrated dance transformed modern dance.[1][2]

Hilde Holger | |

|---|---|

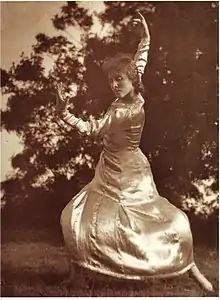

Holger in 1925 | |

| Born | Hilde Sofer 18 October 1905 |

| Died | 22 September 2001 (aged 95) Camden, London |

| Resting place | Goldner's Green Crematorium |

| Nationality | British, Austrian |

| Known for | Dance, choreography and teaching |

| Movement | Expressionism and Integrated dance |

| Spouse | Adershir Kavershir Boman-Behram (1940–1975, 1989–2000) |

| Website | Official website |

Family

Holger came from a liberal Jewish family. She was born in 1905, the daughter of Alfred and Elise Sofer Schreiber.[3] Her father wrote poetry, and had died by 1908. Her grandfather made shoes for the Austrian court.

After Nazi Germany invaded Austria, Holger fled Vienna in 1939, because her entry into England was denied, she went to India.[4] In Mumbai, she met the Parsi homeopath and art loving Dr. Ardershir Kavasji Boman-Behram, they married in 1940.[5] Her mother, step-father, and fourteen other relatives all perished in the Holocaust.

Hilde Holger had two children. The first was born 1946 in India, her daughter Primavera Boman-Behram. In New York, she became a dancer, sculptor and jewelry designer. In 1948, Holger's family emigrated to Britain.[5] Her second child, a son named Darius Boman-Behram, was born in 1949. He had Down syndrome, which inspired Holger to work with physically disabled people.

Work

Hilde Holger started to dance at age six. At that time she was too young to join the Vienna State Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, so she settled for ballroom dancing lessons taken with her sister (Hedi Sofer), until she was accepted to study with radical dancer Gertrud Bodenwieser,[6] then a professor at the Vienna State Academy. They were admirers of the work of Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, as well as the artists of the Secession. Holger soon rose to be Bodenwieser's principal dancer and friend, and toured with Bodenwieser's company all over Western and Eastern Europe. She toured with her own Hilde Holger Dance Group as well. At age eighteen she had her first solo performance in the Viennese Secession. Later in the Viennese Hagenbund and theaters in Vienna, Paris and Berlin, her much-lauded expressionist dance caused quite a stir. Because of her passion for dance, in 1926 she formed the New School for Movement Arts in Palais Ratibor, right in the heart of Vienna. Her children's performances were danced in parks and in front of monuments there.

On 12 March 1938, Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany sent troops into Austria, and adopted a law to unify the country with Austria, at that time it was forbidden for Jews to perform. She received help to flee Austria from her friend Charles Petrach. She decided to go to India because that country's art was the most compelling to Western people, she said at that time.

In India, she had the opportunity to incorporate new experiences into her work, especially the hand movements of Indian dance. Classical Indian dance has over three hundred of them, used to express life and nature. In 1941, Holger founded a new school of dance in Bombay, she took students of all race, religion and nationality without prejudice. Like when she was in Vienna, Holger again took part in the artistic community. Amongst her friends with whom she collaborated with were the Indian dancers Rukmini Devi Arundale, Ram Gopal,[2] Madame Menaka and Uday Shankar.[7] Gopal also danced in Holger's school in Bombay. In 1948 because of the partition of India and the growing violence between Muslims and Hindus she emigrated again, this time to Britain.

Once in England, her Holger Modern Ballet Group performed in parks, churches and theaters. She again opened a new dance school, The Hilde Holger School of Contemporary Dance and remained faithful to their style of teaching that the body and mind must form one unit in order to be a good dancer. Her breakthrough in London, 1951, celebrated Holger with the premiere of "Under the Sea", inspired by the composition by Camille Saint-Saens.

In 1972, she performed a piece titled "Man against flood", it was based on the book of the same name written by Chinese Communist Party member Rewi Alley. It was performed at the Commonwealth Institute with music by Chinese composer Yin Chengzong, and included dancers forming a human wall against a flood of water.[8]

Her performance "Apsaras" (1983) explored her experiences in India. In the summer of 1983 she went back to India, where she had been last in the year 1948. There she worked as a choreographer for a large dance group directed by Sachin Shankar.

Holger was particularly proud of her work with the mentally handicapped. She created a form of dance therapy for children who, like her son Darius, have Down syndrome. Holger was the first choreographer who mixed professional dancers with young adults with severe learning disabilities. In 1968 at the Sadler's Wells, Holger orchestrated "Towards the Light", with music by Edvard Grieg. It was pioneering, innovative, and one of the first integrated dance pieces to be seen on a professional stage.[9]

In 1992, Holger revived four dances from her early repertoire for her student Liz Aggiss, who first performed them, as Vier Tanze, at the Manchester Festival of Expressionism.[10] The pieces were Die Forelle (1923), Le Martyre de San Sebastien (1923), Mechaniches Ballett (1926), and Golem (1937). In the Guardian review, Sophie Constanti wrote that 'Hilde Holger's choreography reaches the British stage at last and triumphs....Together all four pieces danced with great sensitivity and aplomb by Aggiss accompanied by (Billy) Cowie on piano provided a fascinating insight into the lost Ausdruckstanz of central Europe.'[11] In June 1993 the same four solo reconstructions were performed at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) by Liz Aggiss and Billy Cowie with Holger in the audience.[12]

Legacy

Hilde Holger left a lasting impression on three generations of dancers and choreographers. While teaching her standards were high and she was not afraid of risk.[2] She accepted students without prejudice, including students with disabilities, as long as they were sincere. One of her students, Wolfgang Stange, continued her work with people with learning difficulties, like Down syndrome and autism, as well as people with physical disabilities. Stange's Amici Dance Theatre Company which was the first physically integrated dance company in Great Britain, which created a performance titled "Hilde" that was performed at the Riverside Theatre in London in 1996, and at the Odeon in Vienna in 1998. This HILDE Performance in Vienna excited the Ballet Master of the Vienna State Opera Ballet, who in turn put a performance on the stage of the Opera House with people with learning disabilities. These performances were received with great applause!

In her last few weeks Holger still held dance lessons in her basement studio in Camden, London, where she lived for more than fifty years. Her students included Liz Aggiss, Jane Asher, Primavera Boman, Carol Brown, Carl Campbell, Sophie Constanti, Jeff Henry, Ivan Illich, Luke Jennings, Thomas Kampe, Claudia Kappenberg, Cecilia Keen Abdeen, Lindsay Kemp,[13][14] Anneliese Monika Koch, Royston Maldoom OBE, Juliet Miangay-Cooper, Anna Niman, David Niman, Litz Pisk, Kristina Rihanoff, Kelvin Rotardier, Feroza Seervai, Rebecca Skelton, Marion Stein, Sheila Styles, Jacqueline Waltz and Vally Wieselthier.

Archive

After Holger's death in 2001, her daughter Primavera began a journey of discovering the truth about her mother's life as a famous dancer. She started to collate an archive to document her mother's life and career out of the remaining physical legacy.[15] The archive is not on permanent display, although there have been numerous shows that included many of Holger's artifacts.

MoveABOUT

In 2010, six of Holger's students, Boman, Campbell, Kampe, Maldoom, Stange, and Waltz, reunited together to put on a series of talks and dance workshops at The InterChange Studios in Hampstead Town Hall Centre in north London to commemorate Holger's pioneering work in Inclusive Dance, entitled MoveABOUT: Transformation through movement. Each former student led an inclusive dance workshop to celebrate their own unique style of dance therapy, which Holger helped foster in them. These workshops introduced her work to yet another generation of dancers and interested individuals to her pioneering methods and beliefs in the power of dance, which in her own life crossed many boundaries, cultures, and religions.[16][17][18][19]

Literature

At the age of twenty-nine in 1934, Holger was mentioned in the prestigious Art in Austria almanac Kunst in Österreich: Österreichischer Almanach und Künstleradressbuch which listed all the established names in the Austrian arts scene of that year.[20] Afterwards, she became exiled to India in 1939 but it was not until she had relocated again to settle in London a decade later that she started to be mentioned in many books which included her work and photos of herself as a young dancer.

In 1990 a documentation of her entire life and work, across the borders of Austria, India and Britain entitled Die Kraft des Tanzes, Hilde Holger: Wien – Bombay – London: über das Leben und Werk der Tänzeerin, Choreographin und Tanzpädagogin [21] was published by Zeichen und Spuren Verlag publishers in Bremen.

The three photographers, Trčka, Weston and Newton explored nature, the body and the artificial in SCALO's first edition of The Artificial and the Real.[22] She was a frequent model and close personal friend of Trčka.

The Century of Dance, published by the Akademie der Künste in 2019, is a collection of influential pioneers of dance from the twentieth century, like Holger. This volume's scope ranges from Vienna to Berlin between the world wars, from Japanese to American Modern Dance, to New York's Judson minimalist group. It explores the dance art form from various points of view.[23] Dance being ephemeral has no monuments, therefore leading it to be historically weakened in its social recognition in the world.

George gives a supplemental and alternative genealogy of Viennese Modernism in The Naked Truth – Viennese Modernism and the Body as demonstrated by Egon Schiele, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, Hugo Von Hofmannsthal, and to long overlooked ones like dancers, Grete Wiesenthal, Gertrude Bodenwieser, and Holger herself. It was published in 2019 by the University of Chicago Press.[24]

The Hilde Holger Archive, which is run by founding member Primavera (Holger's daughter), has collated an ever growing list of collected works by Holger or on Holger, as well as visual images of her by well known photographers.[25]

Choreography

| Year | Performance | Music | Venue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | Bouree | Johann Sebastian Bach | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Eine Seifenblase | Claude Debussy | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Forelle | Franz Schubert | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Humoreske | Max Reger | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien | Claude Debussy | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Reiter im Sturm | Siegfried Frederick Nadel | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Sarabande | Johann Sebastian Bach | Vienna Secession | |

| 1923 | Trout | |||

| 1923 | Vogel als Prophet | Franz Schubert | Vienna Secession | |

| 1926 | Funeral March for a Canary | Lord Berners | ||

| 1926 | Mechanical Ballet | |||

| 1929 | Chaconne & Variations | George Frideric Handel | ||

| 1929 | Englischer Schafertanz | Percy Aldridge Grainger | ||

| 1929 | Hebraischer Tanz solo | Alexander Veprik | ||

| 1929 | Lebenswende | Karel Boleslav Jirák | ||

| 1929 | Marsch | Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev | ||

| 1929 | The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastien | Claude-Achille Debussy | ||

| 1929 | Mutter Erde | Heinz Graupner | ||

| 1929 | Sarabande und Bourree | Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1929 | Tanz nach Rumaischene Motive | Béla Viktor János Bartók | ||

| 1931 | Javanische Impression | Heinz Graupner | ||

| 1933 | Kabbalistischer Tanz | Vittorio Rieti | ||

| 1936 | Ahasver | Marcel Rubin | Volkshochschule, Vienna | |

| 1936 | Barbarasong | Weill | Volkshochschule, Vienna | |

| 1936 | Engel der Verkündigung | Händel | Volkshochschule, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Flämischer Bilderboden | nach Breughel | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Golem | Wilckens | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Mystischer Kreis | Reti | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Orientalischer Tanz | Graupner | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Passacaglia | Händel | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1937 | Tango | Benatzky | Volksbildungshaus, Stöbergasse, Vienna | |

| 1948 | Annunciation | |||

| 1948 | Emperors new Clothes | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | ||

| 1948 | Pavane | Maurice Ravel | ||

| 1948 | Russian Fairy Tales | Alexander Borodine, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky | ||

| 1948 | Selfish Giant | |||

| 1948 | Tales and Legends in Modern Ballet | |||

| 1948 | Viennese Waltz | Johann Strauss II | ||

| 1952 | Dance with Cymbals on the Indian Ocean | |||

| 1952 | Dance with Tambourines | Fritz Dietrich | ||

| 1952 | Nocturne | Heinz Graupner | ||

| 1952 | Slavic Dance | Antonín Dvořák | ||

| 1954 | Aztec Cult (Sacrifice) | |||

| 1954 | Barbar the Elephant | |||

| 1954 | Old Vienna | |||

| 1954 | Orchid | |||

| 1954 | Rhythm of the East | |||

| 1954 | Selfish Giant | |||

| 1954 | Tibetan Prayer Songs | |||

| 1955 | Angels | |||

| 1955 | Dance Etudes | |||

| 1955 | Galliarde-Siciliano | Ottorino Respighi | ||

| 1955 | Hoops | Georges Bizet | ||

| 1955 | Jazz | Heinz Graupner | ||

| 1955 | Men & Horses | John S. Beckett | ||

| 1955 | Toccata | Paradies | ||

| 1955 | Under the Sea | Camille Saint-Saëns | Sadler's Wells Theatre | |

| 1955 | Valse Caprice | Aram Khachaturian | ||

| 1956 | Etude | |||

| 1956 | Prelude | Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1956 | Theme and Variations | George Frideric Handel | ||

| 1957 | Allegro Vivaci | Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1957 | Bird | |||

| 1957 | Café Dansant | George Gershwin | ||

| 1957 | Egypt | |||

| 1957 | The Hunter and the Geese | |||

| 1957 | Madonna | |||

| 1957 | March | Lev Knipper | ||

| 1957 | Nativity | George Frideric Handel, Franz Schubert, Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1957 | Sale | Johann Strauss II | ||

| 1957 | The Toyshop | Aram Khachaturian | ||

| 1957 | Stranger | Aaron Copland | ||

| 1957 | Witches Kitchen and Walpurgisnight | Paul Dukas | ||

| 1958 | Dance Divertissement | |||

| 1958 | Dance for four Women | Joaquín Turina | ||

| 1958 | Dance with Bells | John S. Beckett | ||

| 1958 | Ritual Fire Dance | Manuel de Falla | ||

| 1958 | Song of the Earth | Antonín Dvořák | ||

| 1960 | Allegro | Arcangelo Corelli | ||

| 1960 | Dawn of Life | |||

| 1960 | The Farmer's Curst Wife | Peter Warlock | ||

| 1960 | Frankie and Johannie | Peter Warlock | ||

| 1960 | Imaginary Invalid | Gioachino Antonio Rossini | ||

| 1960 | Secret Annexe | |||

| 1960 | West Indian Spiritual | |||

| 1961 | Dance for Two | Germaine Tailleferre | ||

| 1961 | Egypt | |||

| 1961 | The House of Bernarda Alba (The Sisters) | Joaquín Turina | written by Federico Lorca | |

| 1961 | Metamorphoses | Ovid | ||

| 1961 | Pierrot | Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1963 | Dance for Men | |||

| 1963 | Dream | Wilckens | ||

| 1963 | Lady Isobel and the Elf Knight | Peter Warlock | ||

| 1963 | Narcissus (The Image) | Heinz Graupner | ||

| 1965 | Ballad of the Hanged (Villons Epitaph) | |||

| 1965 | Cain's Morning | |||

| 1965 | Canticle of the Sun | Johann Pachebel | ||

| 1965 | Creation of Adam & Eve | Olivier Messiaen | ||

| 1965 | Nightwalkers | Olivier Messiaen | ||

| 1965 | Saint Francis and his sermon to the birds | |||

| 1968 | Angelic Prelude – Inspirations | Giuseppe Torelli | ||

| 1968 | Salome | Philip Croot | ||

| 1968 | Towards the Light | Edvard Greig | Sadlers Wells Theatre | |

| 1968 | The Wise & Foolish Virgins | Philip Croot | ||

| 1970 | The Scarecrow | |||

| 1971 | Snowchild | |||

| 1972 | Bamboo | Khatshaturian | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Bauhaus | Erik Satie | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Embrace | Erik Satie | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Flight | Commonwealth Institute | ||

| 1972 | Hieronymus Bosch | Roger Cutts | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Honoré Daumier | Commonwealth Institute | ||

| 1972 | The Hypopatic Doctor | Gioachino Antonio Rossini, Franz Schubert | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Inspirations | Sergei Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Man against Flood | Yin Chengzong | Commonwealth Institute | based on book by Rewi Alley |

| 1972 | Prelude | |||

| 1972 | Renaissance, Scene on Earth, Scene on Heaven | Mompou, Gordon Langford, Banchieri | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Shiva and the Grasshopper | Gordon Langford | Commonwealth Institute | based on the poem by Kipling |

| 1972 | Suspension | Maurice Ravel | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Tranquillity | Alan Hovhaness | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1972 | Tribal Nocturne | Béla Viktor János Bartók | Commonwealth Institute | |

| 1974 | Archaic | |||

| 1974 | Bamboo | Aram Khachaturian | ||

| 1974 | Egypt | Giuseppe Verdi | ||

| 1974 | Hieronymus Bosch | Roger Cutts | ||

| 1974 | The Hunter and the Hunted | |||

| 1974 | Paul Klee Spring Awakening | Béla Viktor János Bartók | ||

| 1974 | Renaissance | Federico Mompou | ||

| 1974 | Spring Awakening | |||

| 1975 | Inspirations | Sergei Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1975 | Mobiles | Alfredo Casella | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1975 | Paul Klee Spring Awakening | Belá Bartók | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1975 | Rockpaintings | Roger Cutts | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1975 | Toulouse Lautrec | Erik Satie | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1976 | The Park | |||

| 1977 | Prelude and Chorale | César Franck | ||

| 1977 | Sacred and Profane Dance | |||

| 1979 | African Poetry | |||

| 1979 | Apsaras | |||

| 1979 | Homage to Barbara Hepworth | Heitor Villa-Lobos | ||

| 1979 | Prelude | Giuseppe Torelli | ||

| 1979 | Tower of Mothers | Carl Orff | ||

| 1979 | Tradisches Ballet | choreographed by Oskar Schlemmer | ||

| 1979 | We are Dancing | Johann Sebastian Bach | ||

| 1983 | The Bow and Arrow | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | Fishes | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | The Letter | Coleridge | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | The Manikin | Coleridge | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | The Penguin Story | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | Pick a Back | Coleridge | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1983 | Poems on a Boy's Painting | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | poems by Ke Yan, pictures by Bu Di |

| 1983 | Sea and Sand | The Hampstead Theatre | poems by Rewi Alley | |

| 1983 | Sea, Clouds, Sparkling Lighthouse, Flames | The Hampstead Theatre | ||

| 1983 | Umbrellas | The Hampstead Theatre | poems by Bu Di and Ke Yan | |

| 1983 | What is a Poem | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1984 | The City | Marcel Rubin | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1984 | Don Quixote | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1984 | Ritual | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1984 | Scherzo | Frédéric Chopin | ||

| 1988 | Children of the Vorstadt | Franz Lehár | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | Children's Games | |||

| 1988 | Death and the Maiden | Franz Schubert | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | Egon Schiele in Memoriam, The Dying Empire | Strauss | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | The Family | Hugo Wolf | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | Flemish Picture Sheet | |||

| 1988 | Fluteplayers | |||

| 1988 | Four Seasons | Antonio Vivaldi | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | Golem | Wilckens | ||

| 1988 | Hands | David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | The Least is the Most | Percussion: David Sutton-Anderson | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1988 | Mechanical Ballet | Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack | ||

| 1988 | Models | Schubert, Schönberg | The Hampstead Theatre | |

| 1995 | Whales | |||

| 2000 | Rhythms of the Unconscious Mind |

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Spirit Levels | herself | Short film |

| 2002 | Hilde Holger: School of Contemporary Dance | herself, posthumous production | Short documentary film. Footage from 1999. |

References

- "Hilde Holger : Central European Expressionist Dancer". 50yearsindance.com. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Hilde Holger: Central European Expressionist Dancer". hildeholger.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Sassenberg, Marina (2009). "Hilde Holger" in Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Jewish Women's Archive

- Pascal, Julia (8 March 2000). "Adi Boman : Scientist on an unresolved search for a cancer cure". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Ardeshir Kavasji Boman Behram 1909–2000". sueyounghistories.com. 22 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Vernon-Warren, B. and Warren, C. (eds.) (1999) Gertrud Bodenwieser and Vienna's Contribution to Ausdruckstanz. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 90-5755-035-0.

- Lee, Rachel (4 April 2019). "Hilde Holger". METROMOD. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Lei, W. (28 October 1972) "Man Against Flood". The New Evening Post (in Chinese).

- Pascal, Julia (26 September 2001). "Hilde Holger : As a dancer and teacher she kept the spirit of German expressionism alive in London". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- 'List of Works', Aggiss and Cowie (eds) Anarchic Dance, Routledge, 2006, p.177

- Sophie Constanti, 'Dancing Diva: Hilde Holger's choreography reaches the British stage at last and triumphs', Arts Section, The Guardian, 9 June 1993, p3-4

- Admin (17 September 2019). "50 over 50 interviewees – Liz Aggiss – Live artist, Dance performer, Choreographer and Filmmaker". Sorcha Ra Blog. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Lindsay Kemp obituary". The Guardian. 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "British choreographer and mime Lindsay Kemp dies". The Guardian. 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Gulliver, J. (04 November 2010) "Prim Boman-Behram and the pioneering dancer Hilde Holger – Old letters reveal her mother's true identity". Camden New Journal.

- "Hilde Holger centenary". Hilde Holger archive. 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "MoveABOUT: Transformation through movement". Austrian Cultural Forum London. 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "MoveABOUT: Transformation through movement". 2019. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2019 – via YouTube.

- "MoveABOUT Jacqueline Waltz's workshop". 2019. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2019 – via YouTube.

- Kunst in Österreich: Österreichischer Almanach und Künstleradressbuch (1934), Leoben.

- Hirschbach, Denny & Rick Takvorian (1990). Die Kraft des Tanzes, Hilde Holger: Wien – Bombay – London: über das Leben und Werk der Tänzeerin, Choreographin und Tanzpädagogin. Bremen: Zeichen und Spuren Verlag.

- Trčka, Anton Josef, Edward Weston & Helmut Newton (1998). The Artificial and the Real. Zurich, Berlin & New York: SCALO.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Verlag, Alexander (2019). The Century of Dance (Exhibition). Berlin: the Akademie der Künste.

- George, Alys X. (2019). The Naked Truth – Viennese Modernism and the Body. New York: University of Chicago Press.

- The Hilde Holger Archive’s full bibliography of collected works on the website of the Hilde Holger: Central European Expressionist Dancer

External links

- Official website

- Leslie Horvitz: The Hilde Holger Biography. hildeholger.com

- Hilde Holger at IMDb