Hexamethylbenzene

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Hexamethylbenzene | |

| Other names

1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexamethylbenzene Mellitene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.616 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H18 | |

| Molar mass | 162.276 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.0630 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 165.6 ± 0.7 °C |

| Boiling point | 265.2 °C (509.4 °F; 538.3 K) |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility | acetic acid, acetone, benzene, chloroform, diethyl ether, ethanol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

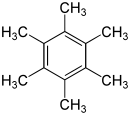

Hexamethylbenzene, also known as mellitene, is a hydrocarbon with the molecular formula C12H18 and the condensed structural formula C6(CH3)6. It is an aromatic compound and a derivative of benzene, where benzene's six hydrogen atoms have each been replaced by a methyl group. In 1929, Kathleen Lonsdale reported the crystal structure of hexamethylbenzene, demonstrating that the central ring is hexagonal and flat[1] and thereby ending an ongoing debate about the physical parameters of the benzene system. This was a historically significant result, both for the field of X-ray crystallography and for understanding aromaticity.[2][3]

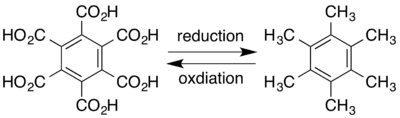

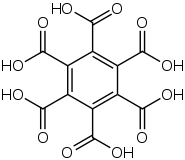

Hexamethylbenzene can be oxidised to mellitic acid,[4] which is found in nature as its aluminium salt in the rare mineral mellite.[5] Hexamethylbenzene can be used as a ligand in organometallic compounds.[6] An example from organoruthenium chemistry shows structural change in the ligand associated with changes in the oxidation state of the metal centre,[7][8] though the same change is not observed in the analogous organoiron system.[7]

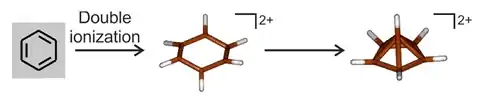

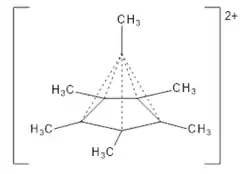

In 2016 the crystal structure of the hexamethylbenzene dication C

6(CH

3)2+

6 was reported in Angewandte Chemie International Edition,[9] showing a pyramidal structure in which a single carbon atom has a bonding interaction with six other carbon atoms.[10][11] This structure was "unprecedented",[9] as the usual maximum valence of carbon is four, and it attracted attention from New Scientist,[10] Chemical & Engineering News,[11] and Science News.[12] The structure does not violate the octet rule since the carbon–carbon bonds formed are not two-electron bonds, and is pedagogically valuable for illustrating that a carbon atom "can [directly bond] with more than four atoms".[12] Steven Bachrach has demonstrated that the compound is hypercoordinated but not hypervalent, and also explained its aromaticity.[13] The idea of describing the chemical bonding in compounds and chemical species in this way through the lens of organometallic chemistry was proposed in 1975,[14] soon after the dication C

6(CH

3)2+

6 was first observed.[15][16][17]

Nomenclature and properties

According to the Blue Book, this chemical can be systematically named as 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexamethylbenzene. The locants (the numbers in front of the name) are superfluous, however, as the name hexamethylbenzene uniquely identifies a single substance and thus is the formal IUPAC name for the compound.[18] It is an aromatic compound, with six π electrons (satisfying Hückel's rule) delocalised over a cyclic planar system; each of the six ring carbon atoms is sp2 hybridised and displays trigonal planar geometry, while each methyl carbon is tetrahedral with sp3 hybridisation, consistent with the empirical description of its structure.[1] Solid hexamethylbenzene occurs as colourless to white crystalline orthorhombic prisms or needles[19] with a melting point of 165–166 °C,[20] a boiling point of 268 °C, and a density of 1.0630 g cm−3.[19] It is insoluble in water, but soluble in organic solvents including benzene and ethanol.[19]

Hexamethylbenzene is sometimes called mellitene,[19] a name derived from mellite, a rare honey-coloured mineral (μέλι meli (GEN μέλιτος melitos) is the Greek word for honey.[21]) Mellite is composed of a hydrated aluminium salt of benzenehexacarboxylic acid (mellitic acid), with formula Al

2[C

6(CO

2)

6]•16H

2O.[5] Mellitic acid itself can be derived from the mineral,[22] and subsequent reduction yields mellitene. Conversely, mellitene can be oxidised to form mellitic acid:[4]

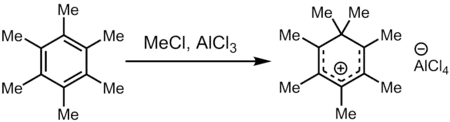

Treatment of hexamethylbenzene with a superelectrophilic mixture of methyl chloride and aluminum trichloride (a source of Meδ⊕Cl---δ⊖AlCl3) gives heptamethylbenzenium cation, one of the first carbocations to be directly observed.

Structure

In 1927 Kathleen Lonsdale determined the solid structure of hexamethylbenzene from crystals provided by Christopher Kelk Ingold.[3] Her X-ray diffraction analysis was published in Nature[23] and was subsequently described as "remarkable ... for that early date".[3] Lonsdale described the work in her book Crystals and X-Rays,[24] explaining that she recognised that, though the unit cell was triclinic, the diffraction pattern had pseudo-hexagonal symmetry that allowed the structural possibilities to be restricted sufficiently for a trial-and-error approach to produce a model.[3] This work definitively showed that hexamethylbenzene is flat and that the carbon-to-carbon distances within the ring are the same,[2] providing crucial evidence in understanding the nature of aromaticity.

Preparation

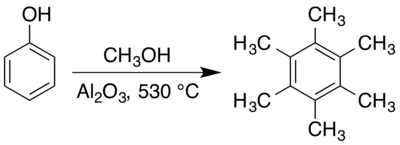

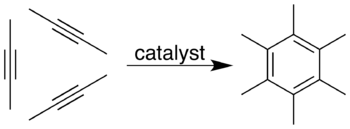

The compound can be prepared by reacting phenol with methanol at elevated temperatures over a suitable solid catalyst such as alumina.[25][20][26] The mechanism of the process has been studied extensively,[27][28][29][30] with several intermediates having been identified.[26][31][32] Alkyne trimerisation of dimethylacetylene also yields hexamethylbenzene[33] in the presence of a suitable catalyst.[34][35]

In 1880, Joseph Achille Le Bel and William H. Greene reported[36] what has been described as an "extraordinary" zinc chloride-catalysed one-pot synthesis of hexamethylbenzene from methanol.[37] At the catalyst's melting point (283 °C), the reaction has a Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of −1090 kJ mol−1 and can be idealised as:[37]

- 15 CH

3OH → C

6(CH

3)

6 + 3 CH

4 + 15 H

2O

Le Bel and Greene rationalised the process as involving aromatisation by condensation of methylene units, formed by dehydration of methanol molecules, followed by complete Friedel–Crafts methylation of the resulting benzene ring with chloromethane generated in situ.[37] The major products were a mixture of saturated hydrocarbons, with hexamethylbenzene as a minor product.[38] Hexamethylbenzene is also produced as a minor product in the Friedel–Crafts alkylation synthesis of durene from p-xylene, and can be produced by alkylation in good yield from durene or pentamethylbenzene.[39]

Hexamethylbenzene is typically prepared in the gas phase at elevated temperatures over solid catalysts. An early approach to preparing hexamethylbenzene involved reacting a mixture of acetone and methanol vapours over an alumina catalyst at 400 °C.[40] Combining phenols with methanol over alumina in a dry carbon dioxide atmosphere at 410–440 °C also produces hexamethylbenzene,[25] though as part of a complex mixture of anisole (methoxybenzene), cresols (methylphenols), and other methylated phenols.[31] An Organic Syntheses preparation, using methanol and phenol with an alumina catalyst at 530 °C, gives approximately a 66% yield,[20] though synthesis under different conditions has also been reported.[26]

The mechanisms of such surface-mediated reactions have been investigated, with an eye to achieving greater control over the outcome of the reaction,[28][41] especially in search of selective and controlled ortho-methylation.[29][30][42][43] Both anisole[31] and pentamethylbenzene[26] have been reported as intermediates in the process. Valentin Koptyug and co-workers found that both hexamethylcyclohexadienone isomers (2,3,4,4,5,6- and 2,3,4,5,6,6-) are intermediates in the process, undergoing methyl migration to form the 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexamethylbenzene carbon skeleton.[27][32]

Trimerisation of three 2-butyne (dimethylacetylene) molecules yields hexamethylbenzene.[33] The reaction is catalyzed by triphenylchromium tri-tetrahydrofuranate[34] or by a complex of triisobutylaluminium and titanium tetrachloride.[35]

Uses

Synthetic uses

Hexamethylbenzene can be used as a ligand in organometallic compounds.

Other uses

Hexamethylbenzene has no commercial or widespread uses. It is exclusively of interest for chemical research.

Reactions

It forms orange-yellow 1:1 adduct with picryl chloride,[44] probably due to π-stacking of the aromatic systems.

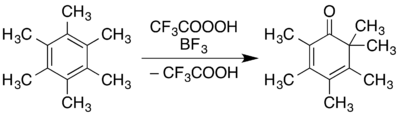

Oxidation with trifluoroperacetic acid or hydrogen peroxide gives 2,3,4,5,6,6-hexamethyl-2,4-cyclohexadienone:[45][27][32])

It has also been used as a solvent for 3He-NMR spectroscopy.[46]

Just as with benzene itself, the electron-rich aromatic system in hexamethylbenzene allows it to act as a ligand in organometallic chemistry.[6] The electron-donating nature of the methyl groups—both that there are six of them individually and that there are six meta pairs among them—enhance the basicity of the central ring by six to seven orders of magnitude relative to benzene.[47] Examples of such complexes have been reported for a variety of metal centres, including cobalt,[48] chromium,[34] iron,[7] rhenium,[49] rhodium,[48] ruthenium,[8] and titanium.[35] Known cations of sandwich complexes of cobalt and rhodium with hexamethylbenzene take the form [M(C

6(CH

3)

6)

2]n+ (M = Co, Fe, Rh, Ru; n = 1, 2), where the metal centre is bound by the π electrons of the two arene moieties, and can easily be synthesised from appropriate metal salts by ligand exchange, for example:[48]

- CoBr

2 + 2 AlBr

3 → [Co(C

6(CH

3)

6)

2]2+

+ 2 AlBr−

4

The complexes can undergo redox reactions. The rhodium and cobalt dications undergo a one-electron reduction with a suitable active metal (aluminium for the cobalt system, zinc for the rhodium), and the equations describing the reactions in the cobalt system are as follows:[48]

- 3 [Co(C

6(CH

3)

6)

2]2+

+ Al → 3 [Co(C

6(CH

3)

6)

2]+

+ Al3+

In the field of organoruthenium chemistry, the redox interconversion of the analogous two-electron reduction of the dication and its neutral product occurs at −1.02 V in acetonitrile[7] and is accompanied by a structural change.[8][50] The hapticity of one of the hexamethylbenzene ligands changes with the oxidation state of the ruthenium centre, the dication [Ru(η6-C6(CH3)6)2]2+ being reduced to [Ru(η4-C6(CH3)6)(η6-C6(CH3)6)],[8] with the structural change allowing each complex to comply with the 18-electron rule and maximise stability.

The equivalent iron(II) complex undergoes a reversible one-electron reduction (at −0.48 V in aqueous ethanol), but the two-electron reduction (at −1.46 V) is irreversible,[7] suggesting a change in structure different from that found in the ruthenium system.

Dication

6_2%252B.png.webp)

6(CH

3)2+

6

The isolation of an ion with composition C

6(CH

3)

6H+

was first reported from investigations of hexamethyl Dewar benzene in the 1960s;[51] a pyramidal structure was suggested based on NMR evidence[52] and subsequently supported by disordered[9] crystal structure data.[53] In the early 1970s theoretical work led by Hepke Hogeveen predicted the existence of a pyramidal dication C

6(CH

3)2+

6, and the suggestion was soon supported by experimental evidence.[15][16][17] Spectroscopic investigation of the two-electron oxidation of benzene at very low temperatures (below 4 K) shows that a hexagonal dication forms and then rapidly rearranges into a pyramidal structure:[54]

6(2%252B)_3D_skeletal.png.webp)

6(CH

3)2+

6 having a rearranged pentagonal-pyramid framework

Two-electron oxidation of hexamethylbenzene would be expected to result in a near-identical rearrangement to a pyramidal carbocation, but attempts to synthesise it in bulk by this method have been unsuccessful.[9] However, a modification of the Hogeveen approach was reported in 2016, along with a high-quality crystal structure determination of [C

6(CH

3)

6][SbF

6]

2•HSO

3F. The pyramidal core is about 1.18 ångströms high, and each of the methyl groups on the ring is located slightly above that base plane[9] to give a somewhat inverted tetrahedral geometry for the carbons of the base of the pyramid. The preparation method involved treating the epoxide of hexamethyl Dewar benzene with magic acid, which formally abstracts an oxide anion (O2−

) to form the dication:[9]

6_(SbF6)2_synthesis.png.webp)

Though indirect spectroscopic evidence and theoretical calculations previously pointed to their existence, the isolation and structural determination of a species with a hexacoordinate carbon bound only to other carbon atoms is unprecedented,[9] and has attracted comment in Chemical & Engineering News,[11] New Scientist,[10] Science News,[12] and ZME Science.[55] The carbon atom at the top of the pyramid is bonding with six other atoms, an unusual arrangement as the usual maximum valence for this element is four.[11] The molecule is aromatic and avoids exceeding the octet on carbon by having only a total of six electrons in the five bonds between the base of the pyramid and its apex. That is, each of the vertical edges of the pyramid is only a partial bond rather than a normal covalent bond that would have two electrons shared between two atoms. Although the top carbon does bond to six others, it does so using a total of no more than eight electrons.[14]

The dication, noting the weak bonds forming the upright edges of the pyramid, shown as dashed lines in the structure, have a Wiberg bond order of about 0.54; it follows that the total bond order is 5 × 0.54 + 1 = 3.7 < 4, and thus the species is not hypervalent, though it is hypercoordinate.[13] The differences in bonding in the dication—the ring having aromatic character and the vertical edges being weak partial bonds—are reflected in variations of the carbon–carbon bond lengths: the ring bonds are 1.439–1.445 Å,, the bonds to the methyl groups are 1.479–1.489 Å,, and the vertical edges are 1.694–1.715 Å.[9] Bachrach rationalised the three-dimensional aromaticity of the dication by considering it as comprising the ring C

5(CH

3)+

5 as a four-electron donor and topped by the CCH+

3 fragment, which provides two electrons, for a total of six electrons in the aromatic cage, in line with Hückel's rule for n = 1.[13] From the perspective of organometallic chemistry, the species can be viewed as [(η5

–C

5(CH

3)

5)C(CH

3)]

.[14] This satisfies the octet rule by binding a carbon(IV) centre (C4+

) to an aromatic η5–pentamethylcyclopentadienyl anion (six-electron donor) and methyl anion (two-electron donor), analogous to the way the gas-phase organozinc monomer [(η5

–C

5(CH

3)

5)Zn(CH

3)], having the same ligands bound to a zinc(II) centre (Zn2+

) satisfies the 18 electron rule on the metal.[56][57]

6(CH

3)2+

6, as drawn by Steven Bachrach[13]

Right: The analogous organometallic complex [(η5

–C

5(CH

3)

5)Zn(CH

3)][56]

It has been commented that "[i]t's super important that people realize that, although we're taught carbon can only have four friends, carbon can be associated with more than four atoms" and added that the "carbon isn't making six bonds in the sense that we usually think of a carbon-carbon bond as a two-electron bond."[12] "It is all about the challenge and the possibility to astonish chemists about what can be possible."[10]

References

- Lonsdale, Kathleen (1929). "The Structure of the Benzene Ring in Hexamethylbenzene". Proc. R. Soc. A. 123 (792): 494–515. doi:10.1098/rspa.1929.0081.

- Lydon, John (January 2006). "A Welcome to Leeds" (PDF). Newsletter of the History of Physics Group (19): 8–11.

- Lydon, John (July 2006). "Letters" (PDF). Newsletter of the History of Physics Group (20): 34–35.

- Wibaut, J. P.; Overhoff, J.; Jonker, E. W.; Gratama, K. (1941). "On the preparation of mellitic acid from hexa-methylbenzene and on the hexachloride of mellitic acid". Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 60 (10): 742–746. doi:10.1002/recl.19410601005.

- Wenk, Hans-Rudolf; Bulakh, Andrey (2016). "Organic Minerals". Minerals – Their Constitution and Origin (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316423684.

- Pampaloni, Guido (2010). "Aromatic hydrocarbons as ligands. Recent advances in the synthesis, the reactivity and the applications of bis(η6-arene) complexes". Coord. Chem. Rev. 254 (5–6): 402–419. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.014.

- Kotz, John C. (1986). "The Electrochemistry of Transition Metal Organometallic Compounds". In Fry, Albert J.; Britton, Wayne E. (eds.). Topics in Organic Electrochemistry. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 83–176. ISBN 9781489920348.

- Huttner, Gottfried; Lange, Siegfried; Fischer, Ernst O. (1971). "Molecular Structure of Bis(Hexamethylbenzene)Ruthenium(0)". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 10 (8): 556–557. doi:10.1002/anie.197105561.

- Malischewski, Moritz; Seppelt, Konrad (2017). "Crystal Structure Determination of the Pentagonal-Pyramidal Hexamethylbenzene Dication C6(CH3)62+". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (1): 368–370. doi:10.1002/anie.201608795. PMID 27885766.

- Boyle, Rebecca (14 January 2017). "Carbon seen bonding with six other atoms for the first time". New Scientist (3108). Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- Ritter, Stephen K. (19 December 2016). "Six bonds to carbon: Confirmed". Chem. Eng. News. 94 (49): 13. doi:10.1021/cen-09449-scicon007. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017.

- Hamers, Laurel (24 December 2016). "Carbon can exceed four-bond limit". Science News. 190 (13): 17. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- Bachrach, Steven M. (17 January 2017). "A six-coordinate carbon atom". comporgchem.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Hogeveen, Hepke; Kwant, Peter W. (1975). "Pyramidal mono- and dications. Bridge between organic and organometallic chemistry". Acc. Chem. Res. 8 (12): 413–420. doi:10.1021/ar50096a004.

- Hogeveen, Hepke; Kwant, Peter W. (1973). "Direct observation of a remarkably stable dication of unusual structure: (CCH3)62⊕". Tetrahedron Lett. 14 (19): 1665–1670. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96023-X.

- Hogeveen, Hepke; Kwant, Peter W.; Postma, J.; van Duynen, P. Th. (1974). "Electronic spectra of pyramidal dications, (CCH3)62+ and (CCH)62+". Tetrahedron Lett. 15 (49–50): 4351–4354. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)92161-6.

- Hogeveen, Hepke; Kwant, Peter W. (1974). "Chemistry and spectroscopy in strongly acidic solutions. XL. (CCH3)62+, an unusual dication". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96 (7): 2208–2214. doi:10.1021/ja00814a034.

- Favre, Henri A.; Powell, Warren H. (2013). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Name 2013. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 9780854041824.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (93rd ed.). CRC Press. p. 3-296. ISBN 9781439880500.

- Cullinane, N. M.; Chard, S. J.; Dawkins, C. W. C. (1955). "Hexamethylbenzene". Organic Syntheses. 35: 73. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.035.0073.; Collective Volume, vol. 4, p. 520

- μέλι in Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940) A Greek–English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Jones, Sir Henry Stuart, with the assistance of McKenzie, Roderick. Oxford: Clarendon Press. In the Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University..

- Liebig, Justus (1844). "Lectures on organic chemistry: delivered during the winter session, 1844, in the University of Giessen". The Lancet. 2 (1106): 190–192. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)64759-2.

- Lonsdale, Kathleen (1928). "The Structure of the Benzene Ring". Nature. 122 (810): 810. Bibcode:1928Natur.122..810L. doi:10.1038/122810c0. S2CID 4105837.

- Lonsdale, Kathleen (1948). Crystals and X-Rays. George Bell & Sons.

- Briner, E.; Plüss, W.; Paillard, H. (1924). "Recherches sur la déshydration catalytique des systèmes phénols-alcools" [Research on the catalytic dehydration of phenol-alcohol systems]. Helv. Chim. Acta (in French). 7 (1): 1046–1056. doi:10.1002/hlca.192400701132.

- Landis, Phillip S.; Haag, Werner O. (1963). "Formation of Hexamethylbenzene from Phenol and Methanol". J. Org. Chem. 28 (2): 585. doi:10.1021/jo01037a517.

- Krysin, A. P.; Koptyug, V. A. (1969). "Reaction of phenols with alcohols on aluminum oxide II. The mechanism of hexamethylbenzene formation from phenol and methyl alcohol". Russ. Chem. Bull. 18 (7): 1479–1482. doi:10.1007/BF00908756.

- Ipatiew, W.; Petrow, A. D. (1926). "Über die katalytische Kondensation von Aceton bei hohen Temperaturen und Drucken. (I. Mitteilung)" [On the catalytic condensation of acetone at high temperatures and pressures. (I. Communication)]. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. A/B (in German). 59 (8): 2035–2038. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590859.

- Kotanigawa, Takeshi; Yamamoto, Mitsuyoshi; Shimokawa, Katsuyoshi; Yoshida, Yuji (1971). "Methylation of Phenol over Metallic Oxides". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 44 (7): 1961–1964. doi:10.1246/bcsj.44.1961.

- Kotanigawa, Takeshi (1974). "Mechanisms for the Reaction of Phenol with Methanol over the ZnO–Fe2O3 Catalyst". Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 47 (4): 950–953. doi:10.1246/bcsj.47.950.

- Cullinane, N. M.; Chard, S. J. (1945). "215. The action of methanol on phenol in the presence of alumina. Formation of anisole, methylated phenols, and hexamethylbenzene". J. Chem. Soc.: 821–823. doi:10.1039/JR9450000821. PMID 21008356.

- Shubin, V. G.; Chzhu, V. P.; Korobeinicheva, I. K.; Rezvukhin, A. I.; Koptyug, V. A. (1970). "UV, IR, AND PMR spectra of hydroxyhexamethylbenzenonium ions". Russ. Chem. Bull. 19 (8): 1643–1648. doi:10.1007/BF00996497.

- Weber, S. R.; Brintzinger, H. H. (1977). "Reactions of Bis(hexamethylbenzene)iron(0) with Carbon Monoxide and with Unsaturated Hydrocarbons". J. Organomet. Chem. 127 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)84196-0. hdl:2027.42/22975.

- Zeiss, H. H.; Herwig, W. (1958). "Acetylenic π-complexes of chromium in organic synthesis". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (11): 2913. doi:10.1021/ja01544a091.

- Franzus, B.; Canterino, P. J.; Wickliffe, R. A. (1959). "Titanium tetrachloride–trialkylaluminum complex—A cyclizing catalyst for acetylenic compounds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81 (6): 1514. doi:10.1021/ja01515a061.

- Le Bel, Joseph Achille; Greene, William H. (1880). "On the decomposition of alcohols, etc., by zinc chloride at high temperatures". American Chemical Journal. 2: 20–26.

- Chang, Clarence D. (1983). "Hydrocarbons from Methanol". Catal. Rev. - Sci. Eng. 25 (1): 1–118. doi:10.1080/01614948308078874.

- Olah, George A.; Doggweiler, Hans; Felberg, Jeff D.; Frohlich, Stephan; Grdina, Mary Jo; Karpeles, Richard; Keumi, Takashi; Inaba, Shin-ichi; Ip, Wai M.; Lammertsma, Koop; Salem, George; Tabor, Derrick (1984). "Onium Ylide chemistry. 1. Bifunctional acid-base-catalyzed conversion of heterosubstituted methanes into ethylene and derived hydrocarbons. The onium ylide mechanism of the C1→C2 conversion". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106 (7): 2143–2149. doi:10.1021/ja00319a039.

- Smith, Lee Irvin (1930). "Durene". Organic Syntheses. 10: 32. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.010.0032.; Collective Volume, vol. 2, p. 248

- Reckleben, Hans; Scheiber, Johannes (1913). "Über eine einfache Darstellung des Hexamethyl-benzols" [A simple representation of hexamethylbenzene]. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. (in German). 46 (2): 2363–2365. doi:10.1002/cber.191304602168.

- Ipatiew, W. N.; Petrow, A. D. (1927). "Über die katalytische Kondensation des Acetons bei hohen Temperaturen und Drucken (II. Mitteilung)" [On the catalytic condensation of acetone at high temperatures and pressures (II. Communication)]. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. A/B (in German). 60 (3): 753–755. doi:10.1002/cber.19270600328.

- Kotanigawa, Takeshi; Shimokawa, Katsuyoshi (1974). "The Alkylation of Phenol over the ZnO–Fe2O3 Catalyst". Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 47 (6): 1535–1536. doi:10.1246/bcsj.47.1535.

- Kotanigawa, Takeshi (1974). "The Methylation of Phenol and the Decomposition of Methanol on ZnO–Fe2O3 Catalyst". Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 47 (10): 2466–2468. doi:10.1246/bcsj.47.2466.

- Ross, Sidney D.; Bassin, Morton; Finkelstein, Manuel; Leach, William A. (1954). "Molecular Compounds. I. Picryl Chloride-Hexamethylbenzene in Chloroform Solution". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1021/ja01630a018.

- Hart, Harold; Lange, Richard M.; Collins, Peter M. (1968). "2,3,4,5,6,6-Hexamethyl-2,4-cyclohexadien-1-one". Organic Syntheses. 48: 87. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.048.0087.; Collective Volume, vol. 5, p. 598

- Saunders, Martin; Jiménez-Vázquez, Hugo A.; Khong, Anthony (1996). "NMR of 3He Dissolved in Organic Solids". J. Phys. Chem. 100 (39): 15968–15971. doi:10.1021/jp9617783.

- Earhart, H. W.; Komin, Andrew P. (2000). "Polymethylbenzenes". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. New York: John Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1615122505011808.a01. ISBN 9780471238966.

- Fischer, Ernst Otto; Lindner, Hans Hasso (1964). "Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen. LXXVI. Di-hexamethylbenzol-metall-π-komplexe des ein- und zweiwertigen Kobalts und Rhodiums" [About Aromatic Complexes of Metals. LXXVI. Di-hexamethylbenzene metal-π-complexes of mono- and bivalent cobalt and rhodium]. J. Organomet. Chem. (in German). 1 (4): 307–317. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)80056-X.

- Fischer, Ernst Otto; Schmidt, Manfred W. (1966). "Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen, XCI. Über monomeres und dimeres Bis-hexamethylbenzol-rhenium". Chem. Ber. 99 (7): 2206–2212. doi:10.1002/cber.19660990719.

- Bennett, Martin A.; Huang, T.-N.; Matheson, T. W.; Smith, A. K. (1982). 16. (η6-Hexamethylbenzene)Ruthenium Complexes. pp. 74–78. doi:10.1002/9780470132524.ch16. ISBN 9780470132524.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Schäfer, W.; Hellmann, H. (1967). "Hexamethyl(Dewar Benzene) (Hexamethylbicyclo[2.2.0]hexa-2,5-diene)". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 6 (6): 518–525. doi:10.1002/anie.196705181.

- Paquette, Leo A.; Krow, Grant R.; Bollinger, J. Martin; Olah, George A. (1968). "Protonation of hexamethyl Dewar benzene and hexamethylprismane in fluorosulfuric acid – antimony pentafluoride – sulfur dioxide". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90 (25): 7147–7149. doi:10.1021/ja01027a060.

- Laube, Thomas; Lohse, Christian (1994). "X-ray Crystal Structures of Two (deloc-2,3,5)-1,2,3,4,5,6- Hexamethylbicyclo[2.1.1]hex-2-en-5-ylium Ions". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (20): 9001–9008. doi:10.1021/ja00099a018.

- Jašík, Juraj; Gerlich, Dieter; Roithová, Jana (2014). "Probing Isomers of the Benzene Dication in a Low-Temperature Trap". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (8): 2960–2962. doi:10.1021/ja412109h. PMID 24528384.

- Puiu, Tibi (5 January 2017). "Exotic carbon molecule has six bonds, breaking the four-bond limit". zmescience.com. ZME Science. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- Haaland, Arne; Samdal, Svein; Seip, Ragnhild (1978). "The molecular structure of monomeric methyl(cyclopentadienyl)zinc, (CH3)Zn(η-C5H5), determined by gas phase electron diffraction". J. Organomet. Chem. 153 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)85041-X.

- Elschenbroich, Christoph (2006). "Organometallic Compounds of Groups 2 and 12". Organometallics (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 59–85. ISBN 9783527805143.

2redox_pi-highlight.png.webp)

Zn(Me).png.webp)